* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download nouns - WordPress.com

Germanic strong verb wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Zulu grammar wikipedia , lookup

Malay grammar wikipedia , lookup

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Arabic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

Udmurt grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ojibwe grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Literary Welsh morphology wikipedia , lookup

Lithuanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Romanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Italian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Russian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ukrainian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Scottish Gaelic grammar wikipedia , lookup

Turkish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Archaic Dutch declension wikipedia , lookup

Latvian declension wikipedia , lookup

Modern Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Swedish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Old Irish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Danish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian nouns wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Ancient Greek grammar wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Serbo-Croatian grammar wikipedia , lookup

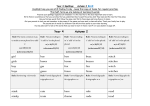

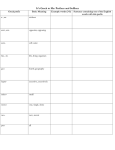

IMPORTANT FEATURES OF OLD ENGLISH GRAMMAR NOUNS Masculine a-stems: These nouns originally had an –a at the end of the stems, lost in OE. These account for the largest group (40%); important since this group (and this group only) formed its nominative and accusative plurals with –as and its genitive singular with –es. Eventually, in Middle English (ME), we’ll see this class expand. Nominative and accusative: sg: stān Genitive (possessive): stānes Dative (“to” someone or thing): stāne pl: stānas stāna stānum Note here the –s plural, the genitive with –es, and the dative plural with –um. This nasal ending in the dative plural is typical of all OE noun declensions. We still say “to whom” or “to him.” The dative sing. ending –e survives in the spelling (final vowel)and pronunciation ([v] not [f]) in alive coming from OE on life. Neuter a-stems: In these the nominative and accusative plural often had no ending. So, we get deor (deer or animal), which declines exactly like stān except in the nom. and acc. plural, where we get deor in both cases. This explains why we have Present Day English (PDE) sing. and pl. deer. Further, by semantic analogy, other animal nouns were attracted to this class. The word fisc (fish), for example, originally was a masculine a-stem, but was drawn to the neuter animal nouns. We still hear some folks occasionally say “fishes.” Such speakers are historically correct, but this ending is generally considered unacceptable. Consonantal or n-stems: These are often called weak nouns, by analogy with the formation of weak adjectives. Any noun with the nom. sg. ending –a is a weak noun or n-stem. All other cases have the ending –an except gen. pl. ena (namena) and dative pl. –um (as is typical). This group survives in PDE pl. oxen. Hundreds of others, such as ME (remember this is Middle English, not Modern English)eyen. Cild belonged to a small group of nouns called r-stems (with the r coming from z by way of rhotacism, so in Germanic these are called z-stems). The r can still be seen in the OE nom./accusative plural cildru. In the development of this plural, children formed out of analogy to the n-stems. That’s how it got the –n ending. You might compare brethren as an alternative form to brothers. Mutated Plurals: In this declension, the endings exerted a direct influence on the stem vowel and caused what we call fronting or i-mutation, which is one of the most common sound changes affecting nouns and can be seen in pairs such as strength vs. strong. What caused i-mutation was the presence of an i in prehistoric OE. It is important to note that this change did not indicate plurality necessarily in OE. The -i was there in the nom./acc. plural as well as in the DATIVE SINGULAR. Therefore, we get e rather than o in these forms. Man vs. men, foot vs. feet, tooth vs. teeth (OE toþ) The genitive plural, as in stān, was –a, so we get fota. We still have this form in PDE in the adjectival five-foot long, which basically means “five of foot” long—an OE genitive of reference or measure (five in reference to foot). Latin has the same construction in satis pecuniae, which means “enough of money.” Similarly, we say “five-mile hike,” not “five miles hike.” Verbal Nouns and participles: The present progressive verb tense (“be” + verb + ing in “I am hunting”) was simply expressed by the present tense: I hunt. The current –ing verb tenses came from the verbal noun: OE Ic ēom on huntunge (with dative –e ending), which means, “I am a hunting” like we have in “A hunting I will go, a hunting I will go. Hi ho the merry-o, a hunting I will go.” So, you can see how this became the PDE progressive. OE did have a present participle, but the ending was –ende. This lasted into ME (remember this means Middle English). Here are some samples: Ealle niht ic stande ofer hie waciende for eofum All night I stand over them watching for thieves. wel sprecende ond yfele þencende well speaking and evil thinking The past participle had ge- added. So we have smeocan (smoke), smeac (smoked), smucan (they smoked) and gesmocen (He got smoked). This prefix still survives in dialect, as in “Farmer Smith has a-hauled off and a-gone and plowed a new plot.” It also makes it’s way to the present participle and other places, as my mother etched in my mind when I was but a wee lad: “When I get a- hold (ge-hold) of you, I’m agonna (ge-gonna) wear out your britches.” Sometimes she’d just say “wear you out,” which is another interesting development of “wear” (OE wearian, “to wear”), but we’ll save that. Ge- was basically an intensifier, and, apparently, the past participle needed some intensifying—and still does in certain places. OE DEMONSTRATIVES The modern definite article the developed from the masc./sing./nom. þe, earlier se. Neuter nom./acc. þæt remains as a singular demonstrative. The early plural of the/that, þa, has been lost; in ME learner confusion led to the borrowing of the original plural of demonstrative þis “this,” which was þas; hence that with a plural those is historically incorrect; in Middle English comes a new plural these to go with this. This is all totally arbitrary. OE se, þæt, sēo (masc./neuter/feminine) = “the, that.” The plural was þa. So, historically, we are incorrect if we say, “That bag belongs to Ms. Jones; those belong to the women who are still here.” “Those” goes with “this.” OE þes, þis, þeos (masc./neuter/feminine) = “this.” The plural was þas, meaning “those” once again. So, historically speaking, we ought to say “this, those,” not “this, these.” PDE makes a definite distinction out of what had been variants in OE. Here’s a usage note from American Heritage: That is sometimes prescribed as the better choice in referring to what has gone before. . . . When the referent is yet to be mentioned, only this is used: This is what bothers me. ADJECTIVES Weak and Strong: In OE, you could say “þā ealdan menn” (weak-“the old men”) or just “ealde menn” (strong). Two entire sets of inflectional endings, strong and weak, developed depending on the absence or presence of a demonstrative, or possessive. Weak: þā blindan menn and have –an endings for the most part. Strong: blinde man and have blindne (Acc), blindum (Dat), etc. Or: dol bearn (foolish child) or dolu bearn (foolish children) in the neuter. Comparative: -ra and superlative –ost were usual patterns: lēof (dear), lēofra (dearer), and lēofost (dearest) a few had –est< earlier –ist, and this -i results in umlaut of the stem vowel: Anglian ald (old), eldest (oldest). Thus, we have old, but elder and eldest, with that back vowel [o] being dragged up to the front by the -i. ADVERBS Normal OE adverb ending was simply –e. At the end of 14th century, this ending was lost with all other –e endings. Thus, PDE slow and easy is more historically correct than –ly forms: “Take it slow and easy.” The same is true for loud, deep, and beautiful in a statement like “He did just beautiful.” The ending –ly comes from OE –lic, meaning “like,” so “quick-like” is historically as correct as “quickly.” “He worked days and nights” comes from OE genitive in which nihtes is a genitive singular. PERSONAL PRONOUNS Dual forms: wit, unc, uncer. These are gradually lost. They forms: the th- comes from Scandinavian. Hforms are OE. Note that ‘em comes from OE dative pl. “him” and is more historically accurate than Scandinavian. Grammatical Gender: Can’t forget this. Bearn is neuter; therefore, an “it” (OE hit). The possessive pronouns were simply min (mine), hiera (their) or eower (your). PDE has possessive adjectives my and their, your plus the possessive pronouns mine, theirs, yours. Thus, we say “what’s mine is yours,” but “that is my book and this is your/their book.” VERBS Highly inflected in present/past tenses; two one-word tenses Much higher proportion of strong verbs in seven classes. PDE has help/helped. OE had helpan (to help), healp (he/she/it helped), hulpon (they helped) and geholpen (helped—past participle). The dialectical “I holp him” is therefore close to being historically correct. Pattern is that strong verbs decrease as weak verbs become more numerous. Reason: the weak system, with the use of dental suffixes to make the past, is more consistent. That’s why children learning a language will put –ed on strong verbs: “Johnny and me swimmed in the pool.” You will also hear this in dialect: “That grass growed and growed in my garden when we got all that rain.” Such speakers are just being logical. Exceptions like OE werian (to wear) and hringan (to ring, were originally weak, but have become strong in PDE. Past participle has ge- prefix, which gets schwa-ed (erodes to schwa?) and becomes a- in “He’s a-gone to the store and will be back directly.” This “a-gone” is more historically correct, if no longer acceptable. See above under participles. Verb “to be” is SUPPLETIVE: Paradigm combines historically unrelated forms of was/were, be, is and am. Verb gān is also suppletive, with preterit ēode. We have go/went (from wend).