* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download `Unroofing` a Rare Toddler Rash

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Poliomyelitis wikipedia , lookup

Trichinosis wikipedia , lookup

Sarcocystis wikipedia , lookup

Oesophagostomum wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Schistosomiasis wikipedia , lookup

Hospital-acquired infection wikipedia , lookup

Anthrax vaccine adsorbed wikipedia , lookup

Eradication of infectious diseases wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Orthohantavirus wikipedia , lookup

West Nile fever wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Marburg virus disease wikipedia , lookup

Middle East respiratory syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Whooping cough wikipedia , lookup

Cysticercosis wikipedia , lookup

Henipavirus wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Neisseria meningitidis wikipedia , lookup

Coccidioidomycosis wikipedia , lookup

Lymphocytic choriomeningitis wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex wikipedia , lookup

Herpes simplex virus wikipedia , lookup

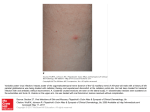

Healthy Baby Practical advice for treating newborns and toddlers. ‘Unroofing’ a Rare Toddler Rash Stan L. Block, MD, FAAP CASE SCENARIOS Case #1 24-month-old male presents with a history of a 2-day rash that his mother claims are “bug bites,” obtained when he was in the yard the evening before. He has been scratching at the lesions, which are limited to his right arm (see Figure 1). He has had a “low-grade fever,” mild rhinorrhea, and a cough for a week but has been well otherwise. Earlier in the week, his sibling had a fever and sore throat, which had been diagnosed as herpangina, but no other family members have had a rash. The boy’s immunizations are up to date. Upon physical examination, you observe a cranky child who is well-nourished, active, and smiling. He has some mild rhinorrhea, but a normal pharynx, neck, lungs, heart, and abdomen. No other skin lesions are present on his body, including the hands and feet. Stan L. Block, MD, FAAP, is Professor of Clinical All images courtesy of Stan L. Block, MD, FAAP. Reprinted with permission. A Figure 1. Maculo-papulo-vesicular crops of lesions noted only on the right arm of a 24-month-old boy. Your differential diagnoses of the skin lesions include: • Insect bites • Early hand-foot-mouth syndrome • Shingles • Impetigo simplex • Molluscum contagiosum. Pediatrics, University of Louisville, and University of Kentucky, Lexington, KY; President, Kentucky Pediatric and Adult Research Inc.; and general pediatrician, Bardstown, KY. Address correspondence to Stan L. Block, MD, FAAP, via email: [email protected]. Disclosure: Dr. Block has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20121018-05 452 | Healio.com/Pediatrics Case #2 An 18-month-old white female presents with a 4-day history of itchy, painful rash on the right lower back (see Figure 2). The mother reports the child has been slightly cranky, with a “low-grade fever” of 100°F, and says the child injured herself on the playground slide Figure 2. An18-month-old white girl with a 4-day history of itchy, painful rash on her lower back. (Note the incidental hemangioma on the left.) PEDIATRIC ANNALS 41:11 | NOVEMBER 2012 Healthy Baby 5 days before. The mother thinks that these lesions may be abrasions. She was also worried about the small blisters on the back, because a child in her daycare had scabies and another child had “MRSA.” The patient has been fully immunized. Your differential diagnoses of the skin lesions include: • Insect bites • Shingles • Traumatic abrasions with secondary impetigo simplex •M olluscum contagiosum with abrasions • Herpes simplex eczematum. initially being small blisters. But the rashes in both cases have remained entirely stationary since the first few days, and you observed no honey-crusted lesions. However, closer examination of both cases (see Figures 3 and 4) sparks a different diagnosis: shingles, or herpes zoster. Several clusters of small vesicles are apparent throughout a distribution of one to three consecutive dermatomes in the thoracic (T1) and lumbar (L3) regions, respectively. As you peruse your textbook on dermatomes, you are certain they have the distribution consistent with shingles. Also, the linear pattern of lesions look quite characteristic for shingles lesions that are several days old. However, you know that shingles in infancy is extremely rare. You must also consider the possibility of eczemata herpeticum. No one in either patient’s family currently has or has ever had symptomatic herpes, the children have never had a history of eczema (nor will they 1 year into the future as you follow both patients), and no preceding lesions or skin problems in the same area were ever noticed by the respective mothers. Neither child had true fever or lymphadenopathy typical of a primary herpes simplex skin infection. Where would the 24-month-old boy and the 18-month-old girl have acquired varicella zoster virus without parental knowledge? Could it have occurred in utero? You know that in order to manifest herpes zoster, the patient must first have been infected with chickenpox; in rare instances a person may have asymptomatic chickenpox before an outbreak of zoster. DIAGNOSES AND DISCUSSION As you carefully examine the skin lesions in Case #2, your first impression is that these may be ruptured bullous impetiginous lesions because the mother had described a few of the lesions as Infant Shingles You remember having read an article previously about a few cases of infant shingles being acquired prenatally, without any damage to the unborn child.1,2 However, if the fetal infection Figure 3. Close-up of lesions in Figure 1 (see page 452). Note the crops of red vesicles in a thoracic dermatome (T1) distribution, typical of herpes zoster reactivation. Figure 4. Close-up of Figure 2. Note the ulcers and vesicles intermixed in an L3 dermatome distribution. No honey-crusted impetiginous lesions were present. PEDIATRIC ANNALS 41:11 | NOVEMBER 2012 occurs before 20 weeks of gestation, fetal death or varicella embryopathy may occur.3 Also, neonatal varicella can be fatal in up to 20% of infants whose mother develops varicella within 5 days before or 2 days after delivery.1 Another article presented a single case report in a 3-month-old with zoster in a lumbar distribution;1 and a Spanish series of 16 children with zoster reported five in utero exposures and two unknown exposures. Interestingly, thoracic dermatome distribution has been observed in 65% to 75% of cases in two other series.2 ‘Unroofing’ Shingles (Herpes Zoster) Varicella zoster virus is a member of the herpes family that causes two specific clinical syndromes: chickenpox and shingles. In the vaccine era, fullblown varicella infection in infancy and now childhood is very uncommon because most mothers have immunity to the varicella virus and over 90% of the pediatric population is vaccinated with the varicella vaccine between age 12 and 15 months.3 However, 15% to 20% of single-dose varicella vaccine recipients will still develop breakthrough chickenpox disease. It is usually much attenuated and occurs within a mean of 28 days after vaccination.4 Herpes zoster, on the other hand, is a reactivation of latent varicella virus that has remained dormant in the spinal ganglia for months to years, either after an initial acquired varicella (chickenpox) infection or more recently after immunization with varicella vaccine. The zoster rash concomitantly starts with symptoms of pain, sometimes burning and itching, and a maculopapular, unilateral rash that over a few days evolves into an erythematous-based vesicular rash that is nearly always distributed within one to three dermatomes (see Figure 5, page 454). It is not supposed to cross the midline. However, your Case #2 provides the exception Healio.com/Pediatrics | 453 Healthy Baby Figure 5. This 10-year-old boy presented with 3 days of painful burning and swelling on the right side of his face, before it erupted with the typical trigeminal dermatome zoster on day 4. Note the swelling and the clusters of vesicles on his right lower cheek, lip, and pre-auricular area. to this “midline” rule as well as to the “age” rule (see Figure 2, page 452).5 The duration of the first-time zoster rash may be from 1 to 3 weeks. Postherpetic neuralgia rarely occurs in children, unlike in adults.3 However, occasionally children may present without a rash and with only pain and swelling, either for the first several days, or as the only manifestation (see Figure 5); this is known as subclinical zoster or zoster sine herpete. Sometimes, it is nearly impossible to differentiate with any certainty due to erythematous macules and vesicular lesions in a near dermatome distribution, whether the rash is due to zoster or herpes simplex (see Figure 6). Performing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) or culture by “unroofing” the lesions may be the only method of determination. Pediatric Zoster Infantile zoster (younger than 12 months old) is supposedly extremely rare and usually results from maternal prenatal varicella infection, which may have been asymptomatic. In fact, most young infants are protected from varicella infection by transplacental maternal antibodies to varicella. The average patient age in such infections is 12 months old, within a range of 2 454 | Healio.com/Pediatrics Figure 6. Uncertain diagnosis. A 3-year-old otherwise healthy white girl with vesicles, ulcers, papules, and a mild secondary cellulitis on her left cheek. The lesion is most likely herpes simplex, but could be herpes zoster in the trigeminal nerve dermatome. She had received a single dose of varicella vaccine at age 12 months. She was treated with oral acyclovir and oral clindamycin (for the cellulitis). No diagnostic testing was performed because it would not have affected management. to 41 months.1 Childhood zoster (> 12 months old) usually occurs in those who became infected either prenatally or within the first year of life.1 The pediatric incidence of zoster has been reported in the post-vaccine era as 0.2 to 0.74 cases per 1,000 personyears.2 But even during the pre-vaccine era, the rate of zoster in those younger than 5 years was reported as low as 20 cases per 100,000.6 To my knowledge, no post-vaccine era incidence data are available for this age group. CASES #1 AND #2 Although you have performed no viral diagnostic testing, such as PCR or culture, “the diagnosis of herpes zoster is based on clinical judgment.”2 Empiric therapy could be initiated with acyclovir (80 mg/kg day four times a day) for 5 days if you were concerned about pain or zoster recurrence, the patient’s very young age, or whether these angrylooking viral lesions might trigger a secondary bacterial infection. Early administration of oral acyclovir may de- crease the pain associated with zoster.7 A closer inspection revealed the more vesicular characteristics of the rash in both children (see Figures 3 and 4, page 453). Although tempted to start an antibacterial for possible staphylococcal infection in Case #2, instead a bacterial skin culture was obtained and the child was asked to return in 2 days; the culture was negative at 48 hours. No signs of staphylococcal infection or scarring developed, and over the following year neither child has shown signs of recurrence, eczema, immune compromise, or malignancy, which has been a concern in the past. Although zoster develops much more frequently in children with neoplasms and organ transplants, conversely, the isolated occurrence of zoster in otherwise healthy children is not associated with an increased risk of neoplasms.2 VACCINE STRAIN-RELATED ZOSTER Both children had received a single dose of varicella vaccine at age 12 months, as is the custom in your office. Neither child ever had a history of chickenpox lesions. Thus, the rash in both cases was most likely due to vaccine strain-related zoster. Despite your consternation about the varicella vaccine normally protecting against zoster breakthrough, the small clusters of vesicular lesions were typical for mild zoster infection. Post-vaccine–related zoster is milder, less readily transmissible, and in the past, occurred less frequently than wild-type virus–induced zoster;6 it is not due to vaccine failure. However, when using PCR analysis for 32 varicella vaccinated cases of zoster (before the widespread routine use of varicella vaccine), 22 cases were vaccine strainrelated and 10 were wild-type virus.4 The nearly universal varicella vaccine policy of this decade, with its secondary “herd” protection, would likely signifi- PEDIATRIC ANNALS 41:11 | NOVEMBER 2012 Healthy Baby cantly reduce the current incidence of wild-type virus–related cases of zoster. Among leukemic children, the vaccine seems to be highly protective against zoster when compared with those who had not received the vaccine.6 At least two theories have been proposed for why a reduced risk of zoster after varicella vaccine occurs: 1) vaccine virus attenuation; or 2) the usual absence of a rash post-vaccine, which is important in order for the virus to travel into the dorsal ganglion and become latent.6 MANAGEMENT OF ZOSTER Due to the classic pattern and appearance of the lesions and the wellappearance of both children, expensive viral testing was not performed. No antiviral therapy was prescribed, which is the preferred course of action in children who are otherwise healthy. You elected to have the parents observe the lesions closely over the next 7 days, and to return to the office if the child PEDIATRIC ANNALS 41:11 | NOVEMBER 2012 developed any honey-crusted lesions or red streaks, the rash spread notably, or fever developed. Management of either chickenpox or shingles typically consists of daily washing of lesions, oral antihistamines, and pain medications as adjunctive therapy for children. Some experts recommend acetaminophen only, avoiding ibuprofen because of the arguable relationship between ibuprofen-treated varicella and group A streptococcal superinfection.7 Most healthy children do not routinely warrant antiviral therapy for uncomplicated zoster, at least after age 1 year. Recurrences (4%) and post-herpetic neuralgia are fairly rare in children too.8 And finally, pediatric uncomplicated zoster infections are not associated with malignancy or immune compromise. REFERENCES 1. Dent AE, Baetz-Greenwalt BA. Herpe zoster in an infant. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2007;46(7):646-649. 2. Rodriguez-Fanjul X, Noguera A, Vicente A, González-Enseñat MA, Jiménez R, Fortuny C. Herpes zoster in healthy infants and toddlers after perinatal exposure to varicella-zoster virus: a case series and review of the literature. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29(6):574-576. 3. Pickering LK, Baker CK, Kimberlin DW, Long SS (eds). Redbook 2012. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. 4. LaRussa P, Steinberg SP, Shapiro E, Vazquez M, Gershon AA. Viral strain identification in varicella vaccinees with disseminated rashes. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19(11):10371039. [Erratum in Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001; 20(1):33.] 5. Paller AS, Mancini AJ. Hurwtiz Clinical Pediatric Dermatology: A Textbook of Skin Disorders of Childhood and Adolescence. 4th ed. Philadelpia: Elsevier Saunders; 2011. 6. Schmid DS, Jumaan AO. Impact of varicella vaccine on varicella-zoster virus dynamics. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):202-217. 7. Gershon AA. Varicella zoster virus. In Feigin RD, Cherry J, Demmler-Harrison GJ, Kaplan SL, eds. Feigin and Cherry’s Textbook of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, 6th edition. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:2077. 8. Kliegman RM MD, Stanton BMD, St. Geme J, Schor NF, Behrman RE (eds). Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics, 19th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Saunders; 2012. Healio.com/Pediatrics | 455