* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download What Your Doctor Said About…..

Survey

Document related concepts

Management of acute coronary syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Pericardial heart valves wikipedia , lookup

Infective endocarditis wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Aortic stenosis wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatic fever wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Antihypertensive drug wikipedia , lookup

Atrial septal defect wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

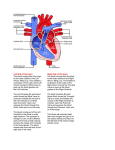

What your doctor said about….. Mitral Regurgitation How does the heart work? The heart is a pump. A muscle pump. It is the size of your fist, and sits in the middle of your chest. It is actually a double pump, one side taking venous blood from your head and your feet, and pumping it onwards to the lungs. In the lungs, blood is enriched with oxygen, and turns bright red. It returns to the left side of the heart, and is pumped onwards to nourish the body. The direction of blood flow is controlled by 4 valves. Within the muscle of the heart is an electrical system. A master spark plug at the top of the heart gives out an electrical signal, which travels to a junction box. From here, the signal moves downwards to the heart muscle and – like a cattle prod – elicits contraction of heart muscle. The heart empties (into the lungs, and the body), and in relaxation, fills again. What is ‘mitral regurgitation’? The mitral valve is on the left side of the heart, controlling the flow of blood from the left atrium to the ventricle. It has 3 leaflets that open towards the pump, and meet one another when the valve is closed. In fact, the mitral valve gets its name from a bishop’s miter (3 cornered hat). Think of the left atrium as a priming chamber, getting blood ready for the main pump. When this chamber contracts, the mitral valve opens. Blood rushes through and fills the left ventricle. The mitral valve then closes, the ventricle contracts, and blood is ejected through another valve (the aortic valve), out to the body. In mitral regurgitation (leak of the valve), the guy wires that anchor the leaflets of the mitral valve are overstretched, loose, or broken – or the leaflets themselves may be damaged. As a result, the leaflets cannot meet properly, and some blood returns to the left atrium when the ventricle contracts. This ‘regurgitation’ means that, with the next heartbeat, the overfilled left atrium, and has to empty more than its usual quota of blood. Of course, it does so. What causes mitral regurgitation? It used to be a common consequence of childhood rheumatic (or scarlet) fever – fortunately rare these days. Longstanding hypertension (high blood pressure) and advancing age are more common causes now. Other causes include infection of the valve (endocarditis), or a dilated heart (cardiomyopathy). It is quite common to have a mild form of this condition; studies suggest 10% of the elderly have it. What symptoms does it cause? Initially, NONE. As the degree of backleak, or regurgitation, progresses from mild to moderate to severe, blood returning to the lungs meets up with an already full left atrium unhappy with accepting more. Symptoms, such as shortness of breath with activity, or fatigue can occur. If the volume of blood in the left atrium causes this chamber to stretch, the electrics of the heart are affected, and palpitations or atrial fibrillation can develop. (In fact, it is not uncommon for these symptoms to bring to your attention the fact that you have an underlying valve problem). Symptoms can take years or decades to develop. What can be done to prevent worsening of mitral regurgitation? You can take the strain off the mitral valve, and its ‘guy wires’, by lowering the pressure in the heart. Essentially, this means lowering blood pressure. Whatever blood pressure you have now, you need less. For example, if you have moderately severe mitral regurgitation and your blood pressure is 150/80, maybe you should aim for 110-120/70. This can be done with blood pressure medications, like HYDROCHLOROTHIAZIDE, ALTACE, DIOVAN, ATACAND, etc. Can the valve ever improve? Yes. Some people have MR due to a large (and weak) heart. As we reduce the size of the heart, and take the strain off by lowering blood pressure, the ‘guy wires’ can resume their normal tension, and the valve may work properly again. Is surgery an option? Yes. Surgery (mitral valve repair or replacement), is usually reserved for those with severe MR causing breathlessness at low or moderate levels of activity, and have not done well with drug therapy. It is a big operation, but not uncommonly done is patients in their 60s, 70s and even 80s. What about palpitations? What should I know about these? ‘Palpitations’ is the name given to an awareness of you heartbeat, either skips or runs of extra beats. You may even feel your pulse ‘miss a beat’. In general, they are of no consequence. They don’t damage your heart, or shorten your life. However, if they are fast and frequent, they can make you tired and breathless, and need treatment. Atrial fibrillation is the name given to a common ‘rhythm problem’ associated with mitral regurgitation and stretch of the left atrium. This rhythm is rapid and irregular, and often fast enough to make one anxious and weak. It can be slowed down with medications (DIGOXIN, VERAPAMIL, DILTIAZEM, METOPROLOL, and others) and sometimes corrected with drugs or an electrical signal. Atrial fibrillation that is constant carries with it a small risk of clot formation in the left atrium, which can be the cause of stroke if it breaks off. For this reason, patients with AF are offered anticoagulant therapy (COUMADIN) to avoid this consequence. Discuss this further with your doctor. Anything else I should know about mitral regurgitation? Yes. If you have had an infection of the mitral valve, or if you have an artificial mitral valve, we encourage you to take an antibiotic when you have dental cleaning, or certain types of surgery. Infection of a heart valve is definitely not a good thing. It further damages the valve, resists treatment, and requires prolonged and intensive intravenous course of antibiotics – even surgery. So if you have a prolonged fever on top of a damaged or artificial valve (endocarditis), it might not be the ‘flu, but something worse.. How do you follow-up patients with MR? Th most accurate way to look at a heart valve is through ultrasound (or ECHO). This can be done every year or so, depending on your symptoms. They are done in the radiology department, and take about 40 minutes to complete. For further information, check out the following websites: http://www.aboutatrialfibrillation.com http://www.americanheart.org http://www.health-heart.org http://www.heartinfo.org HMB –Mitral Regurgitation: May 2010