* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Amr ibn al-A`as, a Realistic Examination of an Early Islamic Military

Imamah (Shia) wikipedia , lookup

Islam and secularism wikipedia , lookup

Sources of sharia wikipedia , lookup

The Jewel of Medina wikipedia , lookup

Islamic culture wikipedia , lookup

Islam and modernity wikipedia , lookup

Usul Fiqh in Ja'fari school wikipedia , lookup

Reception of Islam in Early Modern Europe wikipedia , lookup

Islam and war wikipedia , lookup

Political aspects of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Islamic Golden Age wikipedia , lookup

History of Islam wikipedia , lookup

Medieval Muslim Algeria wikipedia , lookup

Islam and other religions wikipedia , lookup

Historicity of Muhammad wikipedia , lookup

Succession to Muhammad wikipedia , lookup

Satanic Verses wikipedia , lookup

Islamic schools and branches wikipedia , lookup

Egypt in the Middle Ages wikipedia , lookup

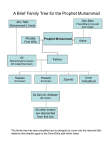

SMALL WARS JOURNAL smallwarsjournal.com Amr ibn al-A’as, a Realistic Examination of an Early Islamic Military Strategic Planner: Expose of the Writings of Dr. Abdel-Raheem Muhammad Ali by Youssef Aboul-Enein American military planners must take the time to discover military campaigns not usually taught in America’s war colleges and service academies. These campaigns should embrace not only the study of insurgencies in Iraq and Afghanistan, but also explore historical conflicts including the campaigns of Prophet Muhammad and his companions. Muhammad (570-632 CE) forever altered warfare in the Arabian Peninsula. From the time of Muhammad’s death in 632 CE, to the year 711 CE, Islamic armies had reached the Iberian Peninsula. However, before delving into the early conflicts of Islam, it is important not to fall into the trap of Islamist militancy by viewing Muhammad from the singular lens of warlord. Regrettably, Islamist militants and al-Qaida mythologize the example of Prophet Muhammad and his companions without truly understanding the challenges and human issues involved in the lives of these men. To gain an understanding of the companions of Prophet Muhammad, and in particular those involved in the conquest of the Levant and Egypt, it is important to study and analyze Arabic sources. This paper will highlight an excellent Arabic biography of Amr ibn al-A’as, a Meccan who opposed Muhammad in Mecca. Amr ibn al-A’as would go to Abyssinia as an emissary of the Meccans, his mission was to retrieve Muslims who sought asylum with the Christian Emperor Najashi. He would eventually convert to Islam and become the conqueror of Egypt and founder of what would become Cairo. The author, Dr. Abdel-Raheem Muhammad AbdelHameed Ali (hereafter referred to as the author) is a Jordanian historian whose doctoral thesis was transformed into a book entitled, “Amr ibn al-A’as al-Qaeed wal Siyasi (Amr ibn al-A’as, the Commander and Politician).” This Arabic book was published in 1998 by Dar al-Zahran in Amman, Jordan and is 174 pages. Another objective of this chapter is to highlight excerpts of this book to demonstrate the importance of Arabic books in the education of future American military planners. The book takes a pragmatic look at Amr ibn al-A’as (hereafter referred to as Amr), his political and military career in the service of the Meccan oligarchy to the rise of Prophet Muhammad and the early formation of the Umayyad Empire. The author uses both Arabic and English sources. His Arabic sources are from the ninth century and include ibn Tabari, ibn Qutaiba, ibn Hisham, and many more historians who wrote 200 years after Muhammad’s death. The biography utilizes forty-one Arabic sources and three English sources to provide a realistic portrait of Amr ibn al-A’as, the once enemy of Prophet Muhammad, who converted to Islam and became the conqueror of Egypt. © 2011, Small Wars Foundation November 1, 2011 Amr’s Origins within the Meccan Oligarchy Muhammad was born in 570 CE, into a society organized around tribes, blood ties and kinship. Tribes organized into a tribal confederacy which clustered around a city center. The apex of the tribal confederation centered on Mecca was the Quraish Tribe. Amr was born in 575 CE, making him five to six years younger than Muhammad. Amr was from the Bani Sahm, a line of the Quraish tribe. An important component of the Quraysh tribe included the Bani Hashim (Muhammad’s line) and the Bani Abdal-Shams (Suffiyan’s line). The prominence of Amr’s family is determined by graves around the Kaaba (the cuboid structure considered by Muslims to be the first house of worship to God built by Adam and rebuilt by Prophet Abraham). Amr’s lineage is traced to the Kenanah tribes, the earliest settlers of Arabia. The Kenanah tribe traces its origins to the Adnan tribe considered to be among the founding tribes of the Arabs. His mother was from the Rabiah tribe of the Banu Anzah. When Muhammad became a Prophet and began preaching in Mecca, he was opposed by Amr’s father A’as ibn Waeel. Among Amr’s wives were women with powerful connections. Notably, the sister of Omar ibn al-Khattab (who would rise to become second caliph) and a sister of Uthman ibn Affan (who would rise to become the third caliph) were both wives of Amr. Amr grew up like many young Arabian males, tribal warfare necessitated proficiency with horse riding, the sword, spear, and bow. He had a reputation as a skilled fighter and was named fursan (knight) of the Quraysh. Aside from his martial skills, Amr was an extraordinary merchant and organizer of caravans. Unlike most Meccan merchants who traded in the Levant and Yemen, Amr also pushed his trade routes to Alexandria, Abyssinia, and the Sinai. Amr had holdings in Mecca and in the gentle resort city of Taif. Additionally, Amr rode alongside Khalid ibn Waleed before their conversion to Islam (Conqueror of the Levant). These experiences made Amr among the most traveled Meccan merchants of pre-Islamic times. Amr would witness the torture and abuse of Muslims and taunting of Prophet Muhammad, Amr noted the severe torture of those without tribal protections like the slave Bilal. During this era, law and order were dictated by tribal loyalties and blood feuds. Among the conflicts that Muhammad participated in before he became a Prophet in 623 CE was the al-Fujar War between the Quraish and Qais tribes. Muhammad and others would question the justice of perpetual blood feuds and the lack of courts to resolve disputes, which were observed in Byzantium. Although the Bani Sahm (Amr’s clan) fought Muhammad in Medina, they did not participate in torturing Muslims. Amr’s Clan Opposes Muhammad in Mecca becomes Emissary to Abyssinia Amr and his clan took a hostile posture towards Muhammad when the Prophet was selected as grand arbiter and leader of Yathrib (Medina). The resolution of decades of internal strife which tore Yathrib apart benefited Mecca. This led Muhammad, a man the Meccans tried to kill, to a city-confederacy that could have potentially blocked access to trade routes to the Levant and Mesopotamia (Iraq). Amr as part of tribal loyalty and loyalty to his clan joined Abu Sufyan to oppose Muhammad and attempted to destroy him while Mecca was much stronger. Amr fought in the Battle of Uhud (625 CE) and commanded a cavalry with Khalid ibn Waleed, fighting Muhammad to a draw. In this battle Muhammad’s uncle, the famous warrior Hamza was killed. Amr would ride his horse probing for a breach in the Battle of the Ditch (626 CE). Muhammad, on the advice of a convert, dug a ditch around Medina, forcing the mobile Meccan 2 smallwarsjournal.com force to lay a siege for which they were ill prepared. After three major battles (Badr, Uhud and Khandaq) with Muhammad, the Meccans selected Amr to travel to Abyssinia as an emissary. His mission was to retrieve those Muslims who sought asylum in Christian Abyssinia. Amr was a wise choice for this mission, even though it was his first diplomatic function. He was selected because of his friendship to the King Najashi (Latin title was Negus). Amr enjoyed good relationships with Abyssinian mercantile families who could pressure the King. Finally, Amr was possessed with common-sense due to the fact he was better traveled than most of his contemporaries. Joining Amr was the Meccan Abdullah ibn Abi Rabiah. Amr’s negotiations began with gifts to King Najashi and his courtiers; this was to lay the ground-work for Amr’s request. Amr asked for the renegade Meccans, called Muslims, on behalf of Mecca. When the request was not immediately granted by the Christian King, Amr resorted to reminding the King of the agreement to return renegade slaves and asked the King to question these Muslims on their views on Jesus Christ. Najashi ruled that although their views on Christ were not orthodox, it differs little from those Christians whose ideas on the trinity were not solidified doctrinally. He stated he did not find any slaves belonging to Meccans. Amr then asked, if among these Muslims, there might be those financially indebted to Meccans, and if so, they must be return. Again, the Christian King found no Muslim in debt to Mecca. Amr was so moved by the eloquence of the Muslim apologia on Christ that he began to consider the importance Islam was having on the Arabian Peninsula. It is important to pause and understand that Arabs have been waiting for their own Prophet, and have felt the line of Ishmael has not had its fair share of Prophets like the Children of Isaac, the Israelites. Upon crossing the Red Sea, Amr came across his old friend and comrade in arms Khalid ibn Waleed and Uthman ibn Talhah, both Meccans, and learned of their conversion to Islam. It is during this time that Amr accepted Islam, from the hands of Muhammad himself, in Medina. Amr fights for Prophet Muhammad Amr’s first combat mission on behalf of Muslims was a raid at Zat al-Salasil in 629 CE. It was a mission to wrestle a trade route to the Levant which was controlled by the Khuzam Tribe. Amr left Medina with 500 forces of Ansar (Medinese) and Muhajiroon (Émigrés and converts from Mecca). He camped during the day and traveled by night. Camp fires were prevented as Amr understood this would betray the size of his force. It is important to note that Amr asserted singular command. This was the key to his success against the Khuzam, gaining a communications route for the Muslims in Medina. There is no mention of Amr in the conquest of Mecca, and only one reference of Amr by Abu Bakr (the first caliph) and his participation in the Battle of Hunayn. After the conquest of Mecca, Amr was sent to neighboring tribal encampments to negotiate and accept fealty on behalf of Muhammad. Amr and the First Caliph Abu Bakr (Conquering the Levant): 632-634 CE The author’s research revealed that little is known about Amr’s role in the Riddah War that occurred after Prophet Muhammad’s death. These wars were instrumental in ensuring the infant Islamic society and its confederacies did not fracture after Muhammad’s death. Amr would not be present in Medina when Muhammad died in 632 CE, reports have him campaigning in the north. Under Abu Bakr, the first caliph, Amr returned to Medina and Mecca and organized a force for the conquest of the Levant. It was composed of tribes from the city confederacies of Mecca, Medina, Taif, the Hawazin, and the Bani Kilab. Abu Bakr gave 3 smallwarsjournal.com command of this army to answer the humiliating defeat of Muslim forces in the Battle of Muta when Muhammad was alive, to Abu Ubaydah ibn Jarrah, with Amr as his deputy. However, Amr used his mercantile and caravanning skills and experience to concern himself with projecting a force of 20,000 to 30,000 north towards the Levant. At some point, Amr’s proficiency came to the attention of Omar ibn al-Khattab (hereafter Omar) who engineered Amr to command this expedition. Omar was instrumental in posturing Abu Bakr to be the first caliph after the death of Muhammad, and he likely saw this well traveled merchant, with a fighting reputation and perhaps the best diplomatic skills in Arabia, as the perfect person to lead the expedition to the Levant. Amr used a multitude of skills to succeed in the conquest of the Levant from Byzantium. These included appealing to tribal impulses giving a speech in which he reportedly said, “We are the children of Ishmael. Noah had divided this land fairly, this land was apportioned to you. Noah gave the Levant (al-Sham) to Yemen (the Hadramaut) to the Arabs who are the children of Shem. We are charged to rectify this injustice and to take what is between your grasp.” Amr also used economics seizing on famines in Arabia and the inability for Arabs to raid one another for survival once they were part of the Islamic confederacy. These circumstances needed an outlet, and the Levant would be this outlet. The first combat was a skirmish at Ghamr Arabat in modern day Jordan, in which 7,500 of Amr’s horsemen harassed 90,000 Byzantine troops in insurgent fashion. At Dathn, Amr’s forces overtook a logistical column that was to resupply large Byzantine formations; they not only plundered the column, but gathered information on the strength and disposition of Byzantine forces. This tactic of raid and retreat, known in Arabic as farr wal karr, was used extensively to exhaust Byzantine forces. The decisive battle between the Muslims and Byzantine forces in the Levant would be fought along the River Yarmuk. Khalid ibn al Waleed would be in command and in Muslim popular history would win the Battle of Yarmuk. This laid open Byzantine forces in the Levant. However, the success had more to do with the forethought of the operation. Amr used his organizational skills and concerned himself with logistics and gathering intelligence. This enabled a mass of Muslim forces to be in one place at one time, and under one singular command thus setting Khalid bin Waleed up for success in 634 CE. Although the book has the overinflated numbers of 36,000 Muslims fighting 140,000 Byzantine forces, the real number is not known, as the Battle of Yarmuk has passed into legend. Nevertheless, there is usable information that can be gathered from these battles. For example, Amr’s military leadership in the conquest of the Levant is characterized by: Looking upon a large force and laying the groundwork through harassment and raiding to disaggregate a large force into smaller demoralized components. Use of War counsels enabled Amr to plan campaigns and more importantly select the right field commanders like Khalid bin Waleed. Utilization of cavalry for reconnaissance and ambush. Delivering speeches that increased the morale of Muslim forces and their destiny. Asking for fresh troops and resupply from Caliph Abu Bakr to exploit opportunities to conduct such mass battles as the Battle of Yarmuk. Amr in the Caliphate of Omar ibn al-Khattab: 634-644 CE The Byzantine forces defeated at Yarmuk River fled toward Egypt. Amr consolidated his victories in the Levant; working against a force of 60,000 Byzantine troops concentrated in 4 smallwarsjournal.com Palestine, and finally defeated them in Ajnadeen. Amr kept Omar, who had succeeded Abu Bakr as second caliph, informed of his progress. The defeat of these 60,000 troops stood between Amr and Jerusalem. Suprisingly, he bypassed this prize by taking the surrounding cities of Ramla, Damascus, Bissan, Tabariah, and Caesaria. In this way he collected support, ensured his flanks, grew stronger, and increased his resources. In 636 CE, Amr laid siege on Jerusalem, this was not a conventional siege, but one designed to draw out the remaining garrison of Byzantine troops in the Levant out into the open where they would be vulnerable to harassing attacks. It was a deceptive maneuver, giving the illusion of a siege, but placed Muslim forces in such a manner as to entice forces to depart the safety of the city. He used the bulk of his 36,000 to 40,000 forces to prevent the logistical resupply of Jerusalem, attack Byzantine staging areas in which forces were arrayed to break the siege, and more importantly monitor dissent from within Jerusalem’s walls. Spying on the mood of the people within Jerusalem added the spread of information to the route in Yarmuk, a psychological blow to Byzantine. The spying also allowed him to conquer Jerusalem through a combination of war and jizya (offering those who paid a tax protection and asylum). He also exploited dissent within Christians over dogma. Byzantine officials imposed a Church doctrine not entirely accepted by all Christians in the Levant. Another element to the success of taking Jerusalem was the hidden hand of Caliph Omar who provided camel trains of resupply to Amr’s forces. In 637 CE, Jerusalem would surrender in a brokered agreement in which Omar left Medina thereby taking control of the city relatively peacefully. The Conquest of Egypt Amr seized on the momentum of his success in the Levant by taking 3,500 horsemen towards Gaza and the Sinai towards Egypt. Caliph Omar disagreed with this action, as he felt Muslim gains in the Levant were barely consolidated. He was concerned about his commander overextending himself and then asking for resupply. Omar’s message never arrived to Amr’s camps or, perhaps, Amr simply ignored the caliph and pressed ahead, taking Arish and Rafah in 641 CE. Amr used both Coptic Christian sympathizers and Muslims who chafed under Byzantine rule, taxation, and discrimination over Christian doctrine. When he reached the Nile, he established a Muslim camp in al-Fustat which would grow to become the city of Cairo. Amr’s army grew from 3,500 to 15,000 along villages in the Nile Delta, working his way north to Alexandria. He then negotiated a jizya (tax) and left Copts to their affairs under Muslim supervision. The biggest prize was the ancient city of Alexandria. There are two stories as to how this city was taken, both of which were highlighted in the book. One story is that Amr negotiated a 2 dinar ransom for each citizen, and then a regular tax. Another more complex story was that Amr sent a Muslim emissary, Awn ibn Malik, who was murdered by Alexandrian leaders. Caliph Omar sent 12,000 troops to reinforce Amr in Egypt, bringing his total number close to 40,000. Amr laid siege to the city, and after half a dozen clashes, negotiated a surrender that included payment of the tax. (The problem with the theory of Amr laying siege to Alexandria was that it was approached by ideal ports from the seaward side; the Muslims did not have a navy to blockade the city.) When Alexandria fell, Amr sent Uqbah ibn Nafeeah ahead to probe Libya and North Africa. The book reduces Amr’s military and diplomatic evolution during this period as follows: 5 smallwarsjournal.com Combining negotiation and the jizya, Coptic sympathizers, and the nuances of regional divisions in Egypt and the Levant combined with force allowed rapid success in Amr’s military campaigns. Amr selectively communicated with Caliph Omar, enabling Arabia to send Amr reinforcements when needed. The use of camels and experienced Arab caravaneers brought supplies to Amr effectively. Siege warfare with Amr was not just preventing external influences but being attuned to divisions inside the cities, looking for a chance to divide leaders and expose those willing to collaborate with Muslims. Amr concerned himself with logistics, which in the view of the author makes him a more significant commander than Khalid ibn Waleed, who was a competent field commander, but did not have the overarching strategic view of Amr. Amr led from the front and not the rear. "Harass and mass”, known in Arabic as farr wal karr, continued to be a central tactic of success for the Muslims. Tactics were fluid in the Muslim ranks compared to the Byzantine and later Persian opponents who fought static wars. Caliphs Uthman and Ali, Amr’s Trying Years: 644-661 CE The chapter on Caliph Uthman is short, as Amr would be isolated from Uthman. The caliph removed Amr from the governorship of Egypt. Uthman’s reign was one characterized by nepotism, yet Amr accepted the decision of the caliph. It would not be until the reign of the fourth Caliph Ali that Amr became active in internal politics of the early Islamic period. When Ali was declared caliph in 656 CE, it was under the cloud of the assassination of Caliph Uthman. Muslims divided into four groups, leading to the first Muslim fitna (division): A neutral group, who isolated themselves. Those who pledged their allegiance to Ali. Those wanting accountability for Uthman’s murder. Those pledging their allegiance to Mua’wiya ibn Abi Sufyan, governor of Damascus. Amr initially stayed neutral, but he was unhappy that Ali chose not to aggressively pursue Uthman’s murderers. Despite Uthman treating him unfairly, he respected the office of caliph and abhorred his murder. Mua’wiya asked for an accounting for his uncle Uthman’s blood and used this as a pretext to declare himself caliph. Caliph Ali was Prophet Muhammad’s cousin, married to Prophet Muhammad’s daughter, and was selected by consensus in Medina to become caliph. There is no real evidence linking Ali to Uthman’s murder, but he was known to criticize Uthman’s policies. What made matters worse is that those who advocated and possibly carried out Uthman’s murder joined Ali’s coalition. Ali and Mua’wiya competed for position to be companions of Prophet Muhammad. Islamist radicals focus on military conflict, but the reality is that they were lobbying war for the support of the sahaba (companions) of Prophet Muhammad. Amr eventually came to Mua’wiya’s side because he believed Uthman’s death had to be adjudicated. In addition, Amr was cognizant of Mua’wiya’s military camp, and was sensitive to the support of Mua’wiya in the Levant and the popular mood of the region to account for the death of Caliph Uthman. The pivotal point leading to Amr joining Mua’wiya was when Ali 6 smallwarsjournal.com incorporated Uthman’s murderers into his caliphate. Additionally, Prophet Muhammad’s wife Aisha, who was the daughter of Abu Bakr, the first caliph, opposed Ali. Amr at the Battle of Siffin on the Banks of the Euphrates (657 CE) Upon arriving in the Levant from Arabia, Amr found its people burning with anger over the assassination of Uthman. Amr declared, “you are in the right (people of the Sham), to call for the blood of Uthman.” Amr’s position within the Quraysh tribe (this tribe included Amr and Prophet Muhammad) found Amr’s clan closer to both Uthman’s and Mua’wiya’s clan than the Banu Hashim (Muhammad’s clan) it is not clear if this played a role, but it made Amr’s allegiance to Mua’wiya easier. Amr began organizing an army of 70,000, becoming standard bearer for Mua’wiya, working to garner support for Mua’wiya’s cause in Kufa and Basra. Amr chose the location of ground forces, placing them between Ali’s army and the Euphrates River (or possibly a tributary, sources differ on which stream of water). This allowed for a constant source of water for Mua’wiya’s forces and gave Mus’wiya control of a coveted resource. Lack of water caused Ali’s forces to break ranks which pressured Ali to negotiate for access to the water supply. The entire month of the Islamic month of Dhul Hijjah 637 CE, was used to negotiate. This lapse of time was significant as the month changed to Muharram where fighting was prohibited. Ali and Mua’wiya followed this Islamic observance which led to continued negotiations as fighting was not an option. At the end of the Islamic month of Muharram, both sides attempted the “harass and mass” (farr wal karr) tactic. Both sides were equally matched tactically and both sides had little appetite for spilling Muslim blood. During the seven day Battle of Siffin Mua’wiya gained the advantage. However, Ali rallied his troops which enabled his forces to strike directly at Mua’wiya, who was reputed to have been in the fifth column in the center. The first four infantry columns in the center line were collapsing under the weight of Ali's forces. Mua’wiyah was under threat. Moreover, Mua’wiya’s ranks, like Amr himself, began to question whether defeating and killing Ali was the objective, or was the object to compel Caliph Ali to punish Caliph Uthman’s murderers. Amr, seeing these columns collapsing and the support of the troops, suggested to Mua’wiya the concept of appealing to God for arbitration. It was Amr who engineered the famous incident, where Mua’wiya’s forces placed pages of the Quran on their lances, spears and swords, as a sign to Ali they wanted to negotiate. Amr suggested this action as he realized that Ali had charisma, legitimacy and a more powerful army than Mua’wiya. He also realized the call for arbitration would give Mua’wiya time to delay the defeat of his forces. Amr saw that returning to the Levant as a defeated force would be a disaster. The negotiation time gained could allow for Amr to coordinate allies and logistics in the Levant and Iraq. Amr’s suggestion was a master stroke, as it divided Ali’s forces psychologically between those who wanted to negotiate and those who saw this as a ploy. Ali, with the shadow of the murdered Caliph Uthman looming, sent Yazid al-Sabei to negotiate a cease fire and begin discussions. A third more violent faction within Ali’s group, the Kharijites (the fringe), not only saw this as a ploy, but felt that Mua’wiya and his companions were apostates worthy of nothing but death, an extreme view with which Ali disagreed. These internal divisions gave months of time for Mua’wiya and Amr to regroup their forces, during the ceasefire negotiated with Ali in 658 CE. The center of political gravity was shifting from Medina to Damascus, and Ali was preoccupied with the suppression of the Kharijites in the Battle of 7 smallwarsjournal.com Naharain in southern Iraq. In 661 CE, Ali was assassinated as he prayed in a mosque in Kufa. He was buried in the Imam Ali Mosque in Iraq, among the holiest sites of Shiite Islam. Ali’s assassin was a member of the Kharijites. Amr and Caliph Mua’wiya: The Birth of the Umayyad Dynasty As a reward for Amr’s service, Mua’wiyah, as the first Umayyad caliph ruling from Damascus, made Amr the governor of Egypt. Amr would serve as Egypt’s Umayyad governor for three years, from about 661 to 664 CE. Amr surmised that Egypt had three major blocks of power: The Coptic Christians, who were Egypt’s original inhabitants; Byzantines, who were the former government and power of Egypt; and Nubians, who shared government with Byzantium in southern Egypt and the Sudan. Amr rapidly sought to re-assure the Coptic Christians by guaranteeing them their freedom to practice their religious observances as long as they accepted Muslim oversight and paid a jizya (tax) for protection. The jizya (the tax levied upon non-Muslims) was set on the annual rising and ebbing of the Nile River. This was important as the Nile River renewed the soil every year with silt. Therefore, the taxation was based on whether or not it was a prosperous year. This was perceived by the people to be a more fair taxation system than prior to Islam. Amr additionally elicited the help of Copts to punish looters and restore order to the city. Amr would invite Coptic patriarchs to be in his presence to discuss theology and to understand Egyptians and its society better. Amr also became a quick study of the power structure of Byzantium Egypt, which included the Byzantine Christian King, the church, and the army. This not only educated Amr on his new subjects, but allowed him to understand the seams of power. This knowledge prepared him to exploit these differences in order to divide and conquer Egypt. Amr would make the most of Coptic Christian and Nubian differences, giving Nubians autonomy in southern Egypt as long as they compensated Muslims in clothes, foodstuffs, and a fixed four dinar per person tax. To undermine Byzantine influence, the capital of Egypt was moved from Alexandria to al-Fustat, which became Cairo. Amr died as governor of Egypt in 664 CE. Conclusion Islamist militant groups show great proficiency in exploiting religious impulses, they do this in part by mythologizing Prophet Muhammad and his companions. Arabic sources provide the clearest understanding of the complex nature of Prophet Muhammad’s companions, giving insight into the real and difficult questions and odds that they faced. The details of Islamic history, that are many times overlooked, are so important for the reason that they reveal pragmatic and extraordinary leaders who used a combination of force and compromise to achieve dominance of Egypt and the Levant. Amr ibn al-A’as cavorted with different Christian sects and held philosophical debates with Christian theologians as a means of understanding the people he governed, and also enabled him to divide and conquer groups. It is inconceivable to see Usama Bin Ladin holding a substantive debate with a non-Muslim over matters of theology. Prophet Muhammad and his companions did just that. Exploring the details of Islamic history exposes how Islamist militants 8 smallwarsjournal.com dumb down Islam, the Prophet and his companions, ignoring whole swaths of details that do not fit the Islamist militant narrative. Islamist militant groups also draw inspiration from the military commanders of the early Islamic conquest. They ignore the reality that Muslims benefited from schisms between Christians over doctrine by eliciting Christian collaboration with the Muslims in the conquest and control of Egypt and the Levant. In governing Egypt, Amr ibn al-A’as worked with Coptic Christians and Nubians to share leadership, retaining Muslim oversight over the entire structure of governing Egypt. Islamist militants write a pseudo-intellectual narrative that Muslims ruled exclusively by force. They do this to justify their violent methodology that is unpopular among whole segments of the Islamic population. Finally, Islamist militants focus obsessively on the methodology of such battles as Yarmuk River in the Levant and al-Qadisiyah in modern day Iraq, drawing inspiration from the tactics that can be reintroduced and expressed with 21st century technology. For these reasons, we cannot afford not to teach early Islamic history and obscure battles of the late antiquity, particularly as the United States becomes fully involved in the Middle East for the foreseeable future. We must get busy translating, analyzing, discussing and educating ourselves on such works as Dr. Abdel-Raheem Muhammad Ali’s biography of the military commander and politician Amr ibn al-A’as. These Arabic works matter to the future of the United States. They offer American military planners a thorough grounding in the history of the region. This intimate knowledge of the region’s military history is a road-map to gaining situational awareness of our friends, as well as our adversaries, in the Middle East. CDR Youssef Aboul-Enein, MSC, USN is Adjunct Islamic Studies Chair at the Industrial College of the Armed Forces. He is author of “Militant Islamist Ideology: Understanding the Global Threat,” (Naval Institute Press, 2010). From 2002 to 2006, CDR Aboul-Enein served as Middle East Country Director and Advisor at the Office of the Secretary of Defense for International Security Affairs. He wishes to thank LCDR Margaret Read, MSC, USN for her edits and comments that enhanced this work. In addition, Mr. Gary Greco provided encouragement to bring to light this Arabic work. Finally, Aboul-Enein wishes to express his appreciation to the John T. Hughes Library in Washington DC and University of Pennsylvania Library for making Abdel-Raheem Ali’s available for study. This is a single article excerpt of material published in Small Wars Journal. Published by and COPYRIGHT © 2011, Small Wars Foundation. Permission is granted to print single copies for personal, non-commercial use. Select noncommercial use is licensed via a Creative Commons BY-NC-SA 3.0 license per our Terms of Use. No FACTUAL STATEMENT should be relied upon without further investigation on your part sufficient to satisfy you in your independent judgment that it is true. Please consider supporting Small Wars Journal. 9 smallwarsjournal.com