* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Culture - faculty.fairfield.edu

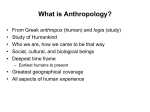

American anthropology wikipedia , lookup

Frankfurt School wikipedia , lookup

Sociological theory wikipedia , lookup

Governmentality wikipedia , lookup

Intercultural competence wikipedia , lookup

Social Bonding and Nurture Kinship wikipedia , lookup

Social theory wikipedia , lookup

Anti-intellectualism wikipedia , lookup

Unilineal evolution wikipedia , lookup

History of anthropology wikipedia , lookup

Reflexivity (social theory) wikipedia , lookup

Legal anthropology wikipedia , lookup

State (polity) wikipedia , lookup

Social history wikipedia , lookup

Ecogovernmentality wikipedia , lookup

Security, Territory, Population wikipedia , lookup

Foucault's lectures at the Collège de France wikipedia , lookup

Origins of society wikipedia , lookup

Ethnography wikipedia , lookup

Other (philosophy) wikipedia , lookup

Political economy in anthropology wikipedia , lookup

History of the social sciences wikipedia , lookup

Ethnoscience wikipedia , lookup

Postdevelopment theory wikipedia , lookup

Cultural anthropology wikipedia , lookup

Social anthropology wikipedia , lookup