* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download chapter-3-lecture-notes

History of Jamestown, Virginia (1607–99) wikipedia , lookup

Slavery in the colonial United States wikipedia , lookup

Province of Maryland wikipedia , lookup

Colonial period of South Carolina wikipedia , lookup

Colony of Virginia wikipedia , lookup

Dominion of New England wikipedia , lookup

Queen Anne's War wikipedia , lookup

Province of New York wikipedia , lookup

Jamestown supply missions wikipedia , lookup

Massachusetts Bay Colony wikipedia , lookup

Province of Massachusetts Bay wikipedia , lookup

Thirteen Colonies wikipedia , lookup

Colonial American military history wikipedia , lookup

London Company wikipedia , lookup

Colonial South and the Chesapeake wikipedia , lookup

English overseas possessions in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms wikipedia , lookup

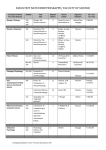

OUT OF MANY A HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN PEOPLE Chapter 3 Planting Colonies in North America 1588 - 1701 © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 1 Part One Introduction © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 2 Chapter Focus Questions In what ways were the Spanish, French, and English colonies in North America similar? In what ways were they different? What was the nature of the colonial encounter between English newcomers and Algonquian natives in the Chesapeake? How did religious dissent shape the history of the New England colonies? What role did the restored Stuart monarchy play in the creation of new proprietary colonies? Why did warfare and internal conflict characterize the late seventeenth century? © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 3 Part Two American Communities: Communities Struggle with Diversity in Seventeenth-Century Santa Fe © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 4 American Communities: Communities Struggle with Diversity in SeventeenthCentury Santa Fe In Santa Fe, the Pueblos clashed with Spanish authorities over religious practices. In 1680, Pope, a Pueblo priest, led a successful revolt that temporarily ended Spanish rule. In 1692, Spanish regained control, loosening religious restrictions. Pueblos observed Catholicism in churches and missionaries tolerated traditional practices away from the mission © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 5 Part Three The Spanish, The French, and The Dutch In North America © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 6 Acoma Pueblo, the “sky city,” was founded in the thirteenth century and is one of the oldest continuously inhabited sites in the United States. In 1598, Juan de Ońate attacked and laid waste to the pueblo, killing some 800 inhabitants and enslaving another 500. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 7 New Mexico Map: New Mexico in the Seventeenth Century Spanish came to Rio Grande valley in 1598 on a quest to find gold and save souls. Brutally put down Indian resistance Colony of New Mexico centered around Santa Fe. The Spanish depended on forced Indian labor for modest farming and sheep raising. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 8 MAP 3.1 New Mexico in the Seventeenth Century By the end of the seventeenth century, New Mexico numbered 3,000 colonial settlers in several towns, surrounded by an estimated 50,000 Pueblo Indians living in some fifty farming villages. The isolation and sense of danger among the Hispanic settlers are evident in their name for the road linking the colony with New Spain, Jornada del Muerto, “Road of Death.” © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 9 New France Map: New France in the Seventeenth Century In 1605, French set up an outpost on the Bay of Fundy to monopolize fur trade. Samuel de Champlain was leader and allied with Hurons against Iroquois. To exploit fur trade, French lived throughout region. Only French Catholics were permitted Quebec City was administrative center of vast French colonial empire. French had society of inclusion, intermarried with Indians. Formed alliances with Indians rather than conquering Missionaries attempted to learn more about Indian customs © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 10 MAP 3.2 New France in the Seventeenth Century By the late seventeenth century, French settlements were spread from the town of Port Royal in Acadia to the post and mission at Sault Ste. Marie on the Great Lakes. But the heart of New France comprised the communities stretching along the St. Lawrence River between the towns of Quebec and Montreal. SOURCE: The New York Public Library/Art Resource, NY. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 11 This drawing, by Samuel de Champlain shows how Huron men funneled deer into enclosures, where they could be trapped and easily killed. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 12 This illustration, taken from Samuel de Champlain’s 1613 account of the founding of New France, depicts him joining the Huron attack on the Iroquois in 1609. The French and their Huron allies controlled access to the great fur grounds of the West. The Iroquois then formed an alliance of their own with the Dutch, who had founded a trading colony on the Hudson River. The palm trees in the background of this drawing suggest that it was not executed by an eyewitness, but rather by an illustrator more familiar with South American scenes. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 13 New Netherland Upon achieving independence, the United Provinces of the Netherlands developed a global commercial empire. Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company In present-day New York, the Dutch established settlements, Dutch opened trade with the Iroquois. Iroquois, through warfare, became the important middlemen of the fur trade with the Dutch. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 14 Part Four The Chesapeake: Virginia and Maryland © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 15 Jamestown and the Powhatan Confederacy King James I issued royal charters to establish colonies. In 1607, Virginia Company founded Jamestown colony. Jamestown colonists saw themselves as conquistadors and were unable to support themselves. Depended on supplies and new colonists from England Algonquian people numbered about 14,000 and a powerful confederacy headed by Powhatan confronted the English. Seeking trade, Powhatans supplied starving colonists with food, but soon abandoned that policy. Warfare ensued until one of Powhatan’s daughters (Pocahontas) was held captive. Powhatan called for peace and Pocahontas married a colonist. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 16 This 1628 engraving depicts the surprise attack of Indians on Virginia colonists in 1622. While it includes numerous inaccuracies (the Indians did not possess such large knives and the colonists lived in far more primitive conditions) the image effectively conveys the surprise and horror of the English. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 17 Tobacco, Expansion and, Warfare The English planting of tobacco supplied cash crop, stimulating migration. Tobacco plantations dominated the economy. Choosing to populate Virginia with English families, the area became a territory of exclusion. The colony grew without having to rely on Indian intermarriage thus pushing the Indians off of their land. Disease claimed many English settlers. Conflicts between Algonquians and English occurred from 1622-1632 and again in 1644. Defeat in 1644 was the last Indian resistance by the Powhatan Confederacy. Chart: Population Growth of the British Colonies in the Seventeenth Century © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 18 FIGURE 3.1 Population Growth of the British Colonies in the Seventeenth Century The British colonial population grew steadily through the century, then increased sharply in the closing decade as a result of the new settlements of the proprietary colonies. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 19 In this eighteenth-century engraving, used to promote the sale of tobacco, slaves pack tobacco leaves into “hogsheads” for shipment to England, overseen by a Virginia planter and his clerk. Note the incorporation of the Indian motif. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 20 Seeing History John Smith’s Cartoon History of His Adventures in Virginia. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 21 Maryland In 1632, King Charles I granted ten million acres at the north end of the Chesapeake Bay to the Calvert family, the Lords Baltimore. Maryland was a “proprietary colony” and because the Calverts were Catholic they encouraged others of the same faith to migrate to America. The economy was based on tobacco plantations. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 22 Indentured Servants Three-quarters of English migrants to the Chesapeake arrived as indentured servants who exchanged passage in return for two to seven years of labor. The first African slaves came to the Chesapeake in 1619 but were more expensive than servants. In terms of treatment, there was little difference between indentured labor and slavery. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 23 Community Life in the Chesapeake Women fared better in the Chesapeake than men. They were fewer in number, suffered lower mortality rates, and many women became widows and through remarriage accumulated wealth. High mortality rates meant families were small and kinship bonds were weak. Little local community life developed and close ties with England were maintained © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 24 Part Five The New England Colonies © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 25 The Social and Political Values of Puritanism English followers of John Calvin were called Puritans because they wanted to purify and reform the English church. Because of Calvinist emphasis on enterprise, Puritanism appealed most to merchants, entrepreneurs, and commercial farmers. Persecution of the Puritans and disputes between the kings of England and Parliament provided context for migration of Puritans to New England. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 26 Early Contacts in New England Map: European Colonies of the Atlantic Coast, 1607-39 French and Dutch established trade connections with Algonquians in region. From 1616 to 1618, a disease epidemic wiped out whole villages and disrupted trade. Native population dropped from an estimated 120,000 to under 70,000. The remaining Indians societies on the Atlantic coast were too weak to resist the planting of English colonies. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 27 MAP 3.3 European Colonies of the Atlantic Coast, 1607–39 Virginia, on Chesapeake Bay, was the first English colony in North America, but by the midseventeenth century, Virginia was joined by settlements of Scandinavians on the Delaware River and Dutch on the Hudson River, as well as English religious dissenters in New England. The territories indicated here reflect the vague boundaries of the early colonies. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 28 Plymouth Colony The first English colony in New England was founded by Separatists, better known as the Pilgrims. Separatists believed they needed to found independent congregations to separate themselves from the corrupt English church. In 1620, they sailed for American and signed the Mayflower Compact, the first document of selfgovernment in America, before landing at Plymouth. With help from the Indians, the Plymouth colony eventually established a community of self-sufficient farms. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 29 The Massachusetts Bay Colony In 1629, a group of wealthy Puritans was granted a royal charter to found the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Between 1629 and 1643, approximately 20,000 people relocated to Massachusetts. Massachusetts was governed locally by a governor and elected representatives. This was the origin of democratic suffrage and bicameral division of legislative authority. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 30 Governor John Winthrop, ca. 1640, a portrait by an unknown artist. Winthrop was first elected governor of Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629, then was voted out of office and reelected a total of twelve times. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 31 Dissent and New Communities Puritans emigrated for religious freedom but were not tolerant of other religious viewpoints. In 1636, when Thomas Hooker disagreed with church policy, he led his followers west and founded the beginning of the colony of Connecticut. In 1636, Roger Williams was banished because of his views on religious tolerance and founded the colony of Rhode Island. In 1638, Ann Hutchinson and her followers moved to Rhode Island. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 32 Indians and Puritans Unlike the French and Dutch, the primary interest of the English was acquiring land. Disease had depopulated parts of New England making it seem there was open land. The English used a variety of tactics to pressure native leaders into relinquishing their lands. The English and their Narragansett allies defeated the Pequots, who were allies of the Dutch. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 33 The first map printed in the English colonies, this view of New England was published in Boston in 1677. With north oriented to the right, it looks west from Massachusetts Bay, the two vertical black lines indicating the approximate boundaries of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The territory west of Rhode Island is noted as an Indian stronghold, the homelands of the Narraganset, Pequot, and Nipmuck peoples. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 34 The New England Merchants Initially, the New England economy was based on sales of land and supplies to migrants. New England merchants developed diversified trade of fish, farm products, and lumber. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 35 Community and Family in Massachusetts The close-knit, well-ordered families and communities of New England were not “puritanical” as the word is used today. Settlers clustered near the town center, building churches and schools. Society was male-dominated and women were mistrusted as shown by various witchcraft scares. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 36 The Mason Children, by an unknown Boston artist, ca. 1670. These Puritan children— David, Joanna, and Abigail Mason—are dressed in finery, an indication of the wealth and prominence of their family. The cane in young David’s hand indicates his position as the male heir, while the rose held by Abigail is a symbol of childhood innocence. SOURCE: The Freake-Gibbs Painter (American, Active 1670), “David, Joanna, and Abigail Mason,” 1670. Oil on canvas,39 ½ x 42 ½; Frame 42 ¾ x 45 ½ x 1 ½ in. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3 rd to The Fine Art Museums of San Francisco, 1979.7.3. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 37 The Salem Witch Trials The cultural mistrust of women manifested in public witch scares. The Salem witch scare reflected social tensions. The crisis exposed a dark side of Puritan thinking about women. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 38 Part Six The Proprietary Colonies © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 39 The Proprietary Colonies Map: The Proprietary Colonies © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 40 MAP 3.4 The Proprietary Colonies After the restoration of the Stuart monarchy in 1660, King Charles II of England created the new proprietary colonies of Carolina, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Jersey. New Hampshire was set off as a royal colony in 1680, and in 1704, the lower counties of Pennsylvania became the colony of Delaware. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 41 Early Carolina King Charles II initiated the founding of new colonies along the Atlantic Coast. In 1663, the colony of Carolina was chartered but soon divided into a northern and a southern colony. North Carolina was home to 5,000 small farmers and large tobacco planters, many from Virginia. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 42 From New Netherland to New York The growth of the English colonies led the Dutch West India Company to promote migration to their New Netherland colony. Competition with England caused a series of three wars that transferred New Netherland to the English. King Charles II gave the colony to his brother the Duke of York and renamed it New York. New York boasted the most heterogeneous society in North America. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 43 The earliest known view of New Amsterdam, published in 1651. Indian traders are shown arriving with their goods in a dugout canoe of distinctive design known to have been produced by the native people of Long Island Sound. Twenty-five years after its founding, the Dutch settlement still occupies only the lower tip of Manhattan Island. SOURCE: Fort New Amsterdam, New York, 1651. Engraving. Collection of the New York Historical Society, 77354d. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 44 The Founding of Pennsylvania In 1681, King Charles II repaid a debt to William Penn’s father by granting the younger Penn a huge territory west of the Delaware River. Penn traveled to Pennsylvania and oversaw the organization of Philadelphia. Penn was a Quaker and established his colony as a “holy experiment.” Penn purchased the land from the Algonquians, dealing fairly with the Indians. Immigrants flocked to Pennsylvania which later became America’s breadbasket. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 45 The Delawares presented William Penn with this wampum belt after the Shackamaxon Treaty of 1682. In friendship, a Quaker in distinctive hat clasps the hand of an Indian. The diagonal stripes on either side of the figures represent the “open paths” between the English and the Delawares. Wampum belts like this one, made from strings of white and purple shell beads, were used to commemorate treaties throughout the colonial period, and were the most widely accepted form of money in the northeastern colonies during the seventeenth century. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 46 Part Seven Conflict and War © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 47 Conflict and War In the last quarter of the seventeenth century, intertribal and inter-colonial rivalry stimulated violence that extended from Santa Fe to Hudson’s Bay. Map: Spread of Settlement: British Colonies, 1650-1700 © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 48 MAP 3.5 Spread of Settlement: British Colonies, 1650– 1700 The spread of settlement in the English colonies in the late seventeenth century created the conditions for a number of violent conflicts, including King Philip’s War, Bacon’s Rebellion, and King William’s War. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 49 King Philip’s War Relations between the Plymouth colonists and Pokanokets deteriorated in the 1670s. The colonists attempted to gain sovereign authority over the land of King Philip (Metacom). After peaceful coexistence lasting forty years, the Indians realized that the colonists were interested in domination. King Philip led an alliance of Indian peoples against the United Colonies of New England and New York in King Philip’s War. By 1676, in part due to an alliance between the Iroquois Confederacy and the English, King Philip’s War ended in defeat. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 50 Indians and New Englanders skirmish during King Philip’s War in a detail from John Seller’s “A Mapp of New England,” published immediately after the war. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 51 Bacon’s Rebellion and Southern Conflicts In the 1670s, conflicts erupted between Virginia settlers and the Susquehannocks on the upper Potomac River. Nathaniel Bacon demanded the death or removal of all Indians from the colony. The governor attempted to suppress unauthorized military expeditions. Bacon and his followers rebelled against Virginia’s royal governor, pillaging the capital of Williamsburg. When Bacon died of dysentery, his rebellion collapsed. Planters feared former servants would remain disruptive and turned to African slave labor. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 52 The Glorious Revolution in America In 1685, King James II attempted to increase royal control by combining New York, New Jersey, and the New England colonies into the Dominion of New England. Colonial governments were disbanded and Anglican forms of worship were imposed. The Glorious Revolution of 1688 overthrew King James and colonial revolts broke out in favor of the Glorious Revolution. Parliament installed William and Mary as king and queen. The new rulers abolished the Dominion of New England and colonists revived assemblies and returned to selfgovernment. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 53 King William’s War In 1689, England and France began almost 75 years of warfare over control of the North American interior. English gains in the fur trade led to the outbreak of King William’s War. The war ended inconclusively in 1697. England feared loss of control of the colonies and replaced proprietary rule with royal rule. This signified the tightening of imperial reigns over the colonies of North America. © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 54 Part Eight Conclusion © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 55 © 2009 Pearson Education, Inc. 56