* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

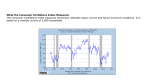

Download Interest Rates and Their Role in the Economy during Transition. The

Survey

Document related concepts

Non-monetary economy wikipedia , lookup

Pensions crisis wikipedia , lookup

Business cycle wikipedia , lookup

Inflation targeting wikipedia , lookup

Modern Monetary Theory wikipedia , lookup

Real bills doctrine wikipedia , lookup

Austrian business cycle theory wikipedia , lookup

Quantitative easing wikipedia , lookup

Fear of floating wikipedia , lookup

Exchange rate wikipedia , lookup

Money supply wikipedia , lookup

Early 1980s recession wikipedia , lookup

Transcript