* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download NIE10x301Sponsor Thank You (Page 1)

History of supernova observation wikipedia , lookup

Chinese astronomy wikipedia , lookup

Fermi paradox wikipedia , lookup

Leibniz Institute for Astrophysics Potsdam wikipedia , lookup

History of astronomy wikipedia , lookup

James Webb Space Telescope wikipedia , lookup

Corona Borealis wikipedia , lookup

Rare Earth hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Gamma-ray burst wikipedia , lookup

Auriga (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Modified Newtonian dynamics wikipedia , lookup

Canis Minor wikipedia , lookup

Space Interferometry Mission wikipedia , lookup

Observable universe wikipedia , lookup

Cassiopeia (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Corona Australis wikipedia , lookup

Spitzer Space Telescope wikipedia , lookup

Aries (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Malmquist bias wikipedia , lookup

Stellar kinematics wikipedia , lookup

Astrophotography wikipedia , lookup

International Ultraviolet Explorer wikipedia , lookup

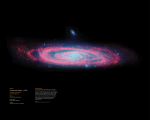

Andromeda Galaxy wikipedia , lookup

Cygnus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Star formation wikipedia , lookup

Aquarius (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

High-velocity cloud wikipedia , lookup

Cosmic distance ladder wikipedia , lookup

Perseus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Future of an expanding universe wikipedia , lookup

Corvus (constellation) wikipedia , lookup

Hubble Deep Field wikipedia , lookup

Observational astronomy wikipedia , lookup

“What’s Up” “Springtime: Galaxies!” April 24 - Mid May actually a bit bigger than our Milky Way, and is moving towards us; in three billion years, the two will collide! Many of the familiar galaxies in Messier’s list are contained in vast clusters lying in the direction of the constellations Ursa Major, Leo, Virgo, and others such as Coma and Hercules. Let’s have a look. Some History: Ancient peoples never had to contend with artificial light pollution, and on moonless nights a somewhat mottled band of ghostly light arcing across the sky was always prominent. To the unaided eye this appeared quite distinct from the brilliant stars. The Kung Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert in Africa thought it looked like a spinal column and called it the “Backbone of Night”; the ancient Chinese called it “The Silver River”. We refer to it as “The Milky Way”, from the Greek legend whereby the goddess Hera squirted breast milk across the Heavens. “Gala” ( ) is in fact Greek for “milk”, and is the root of the word for “galaxy”. Observing Galaxies: For observing other than M31, you’ll need at least 10x50 binoculars or a small telescope. A good place to start spring time galaxy hunting is the familiar Big Dipper (part of the constellation Ursa Major), prominent in the northern sky year-‘round but poised almost overhead at this time of year after dark. A bright pair of galaxies, M81 and M82, can be found by drawing a diagonal line across the “bowl” of the Dipper, from the star Phecda to Dubhe (see chart), and extending this line to the same distance beyond the bowl. M81 is another spiral galaxy, the largest of its own small group, and is nicknamed Bode’s Galaxy after its discoverer, Johann Elert Bode (1747-1826). M82, an irregular galaxy, is undergoing a tremendous burst of star formation and is also called a starburst galaxy. It’s also sometimes called The Cigar Galaxy because it’s seen almost edge-on. They’re both about 12 million ly away, and easily glimpsed together in 10x50 binoculars. M51 lies under the end of the “handle” of the Big Dipper. To find it, imagine a 30-60-90 triangle, placed upside down between the handle’s end star (Alkaid) and second-last star (the double star Mizar and Alcor), with the short side extending down from Alkaid; M51 will be near the tip. Visualizing an equilateral triangle between these two handle stars, pointing upwards instead, brings us to M101 (at the triangle’s apex), a large and faint spiral galaxy. With a small telescope you can find fainter M108 and M109 near the bowl stars Merak and Phecda, respectively. Classifying Galaxies: Galaxies come in many shapes and sizes, but can be arranged into three large groups. The smallest are scruffy little dwarf galaxies comprising “only” millions of stars in a rough blob. Dwarf galaxies are often satellites of larger galaxies, the way moons orbit planets. The rest are broadly divided into elliptical and spiral galaxies. Our own Milky Way is a pretty typical spiral containing ~200 billion stars in spiral arms making up a flat disk 100,000 light years (ly) across and 2500 ly thick, and a central bulge of older stars perhaps 16,000 ly thick. The Sun is 28,000 ly from the centre, on the inside edge of a spiral arm. (A “light year” is the distance light travels in a year, or about 9500 billion km). Many spirals have bars protruding from the bulge at the ends of which spiral arms begin; we now know the Milky Way to also be a barred spiral galaxy. It has a family of about a dozen dwarfs (most of which are difficult to see clearly). Unlike spirals, elliptical galaxies are relatively featureless balls of stars flattened to various degrees, but they cover an enormous range of sizes, from dwarfs to titanic giants formed from galaxy mergers with over a trillion stars! Galaxies are typically spread throughout the universe in groups and clusters. Our own neck of the woods in the cosmos is called the Local Group, and in it our Milky Way is joined by two other spiral galaxies that are visible even with the unaided eye in a rural, moonless sky (making them the largest objects you can see without aid!). They’re both in the same part of the sky, in or near the constellation Andromeda; the great Andromeda Galaxy (M31) and the Triangulum Galaxy (M33). A pair of binoculars will easily reveal M31 to be a smooth, flat oval of light that appears to be eight times wider than the Full Moon (which appears to be ? degree wide)! In fact, the Andromeda Galaxy was first noted by the ancient Persian astronomer Al Sufi in 905 A.D., well before the telescope was invented. M31 is the nearest large galaxy, 2.3 million ly away, is W E M81 The constellation Leo, rising in the east after dark in the Spring, is another rich hunting ground for galaxies; the Leo Group resides in space behind it, about 40 million ly distant. Two groups of galaxies are visible under the belly and haunches of the Lion; a star chart will help you. M65 and M66 lie together under the haunches (“below” the star theta-Leo, also called Chertan), and M95 (a picturesque barred spiral), M96 and M105 (ellipticals) lie below the belly, about a third of the way towards Leo’s brightest star, Regulus. M105 is notable. Many galaxies, both spiral and elliptical, appear to have giant black holes at their centres; M105 has one with a mass of about 50 million solar masses! (The Milky Way is thought to contain a 3 million solar mass black hole). The Virgo Cluster, however, has to be the richest and best-known galaxy cluster. It’s further than the Leo Group (60 million ly) so its members are fainter and you’ll need a telescope. Amongst the cluster’s 2000 members are over a dozen Messier galaxies, located about 10 degrees (about the width of your outstretched fist) east of the “hind quarters” star in Leo, bright Denebola. To explore this cluster a star chart in magazines like “SkyNews”, “Astronomy” or “Sky and Telescope” will get you started, and a book like Terry Dickinson’s recommended “Nightwatch” will dig a little deeper; the region is so rich that dedicated star atlases usually include charts of just the Virgo Cluster. It is so big that its gravity is pulling our Local Group towards it! At the heart of this rich cluster is the giant elliptical galaxy M87, with ten times the stars of our home galaxy! Rich galaxy clusters generally have giant ellipticals at their centres, probably the result of many mergers of normal galaxies throughout the cluster’s history. Their cannibalized blackholes also merge; the central black hole in M87 is a 3 billion solar mass monster! Chris Stevenson RASC, St. John’s Centre ACTIVITIES 1. Galaxies are described in this article as large grouping of stars, not unlike a community. Can you find other examples of groups /communities within The Telegram? 2. In Astronomy visual descriptions are used to describe what an object looks like; the above article contains many examples of this. Can you find more of these visual descriptions throughout The Telegram? For more activities go to www.thetelegram.com and click on Brought to you by Point this astronomical chart toward North and match the stars with those in the real sky. S Planets Viewable in a pair of Binoculars or small telescope Mercury - (magnitude –1.5) is emerging from the glow of sunset. Venus - (magnitude –4.2) is low in the dawn. Look for it above the eastern horizon about 20 or 30 minutes before sunrise. Mars - (magnitude +1.2) is both dim and very low in the sunrise glow. Jupiter - (magnitude –2.1, in Capricornus) shines low in the southeast during early dawn. Saturn - (magnitude +0.6, near the hind foot of Leo) shines in the southeast at dusk. Saturn's rings are 3 1/2 ° from edge on and will open to a maximum of 4° in May. Uranus - (6th magnitude) is hidden low in the sunrise glow. Neptune - (8th magnitude) is also hidden in the glow of dawn. Pluto (dwarf planet) - (14th magnitude, in northwestern Sagittarius) is located in the southeast before the first light of dawn. Magnitude: A number denoting the brightness of a star or other celestial object. The higher the magnitude, the fainter the object. For example, a 1st-magnitude star is 100 times brighter than a 6th-magnitude star. Moon Waxing First Quarter Full Last Quarter Waning New April 30 May 1 May 9 May 17 April 19 April 25 New Moon - If the Moon is on the same side of the Earth as the Sun, then the face of the Moon that would ordinarily be seen from the Earth is no longer illuminated by the Sun’s rays and therefore cannot be seen. Comets Viewable in a pair of Binoculars or small telescope C/2008 T2 (Cardinal) (Magnitude 9.2) is moving through the constellation Auriga, and can be glimpsed with a small telescope or binoculars. It is expected to reach a visual magnitude of around 8 in mid June. Comet C/2009 F6 (Yi-SWAN) A small 8th magnitude comet is now making its way slowly across Cassiopeia toward Perseus and should be within reach of small telescopes for most of April and May 2009. For more detailed information on finding these objects log onto www.rasc.ca/stjohns/ under Observing on the lefthand side of the web page click bright comets. WARNING!“ When using a telescope or binoculars, always be sure NEVER TO LOOK AT THE SUN! This can cause serious and permanent eye damage. To be safe, always make sure the Sun is fully set below the horizon before going outside with your telescope or binoculars.” pa news pe r s. Open m in ds n pe Newspaper In Education THE TELEGRAM 0-3636427 Lord Rosse’s drawing of the Whirlpool Galaxy, M51, next to a contemporary photograph. S N t har O In the mid-19th century the French comet-hunter Charles Messier (17301817) compiled his famous list of 110 “faint fuzzies”, non-comet “nuisances” for him but popular targets for astronomers ever since. Sir William Herschel (1738-1822) and other astronomers would turn larger and larger telescopes towards these catalogued “nebulosities” and discover many to have a generally circular, and often spiral-shaped, structure; they called these spiral nebulae, and presumed them objects within our own “island universe”. A famous example would be M51, nicknamed The Whirlpool Galaxy today, which was studied in 1845 by William Parsons, the 3rd Earl or Rosse, with the giant telescope he had just built. His careful painting clearly shows M51’s spiral nature. It wasn’t until 1925 when Sir Edwin Hubble (after whom the space telescope is named) that it was realized these “spiral nebulae” were a separate “island universes” like our own – suddenly the cosmos got a whole lot larger! g rin C tar M82 Illustration by: Shawn Martin After the astronomical telescope was refined and put to use first by Galileo in 1609, and by many others in the decades and centuries that followed, it was seen that, under some magnification, much of the visible Milky Way resolves into thousands and thousands of stars; not milk at all! You can demonstrate this to yourself with a simple pair of binoculars under a dark sky. Towards the constellation Sagittarius (relatively low in the south during summer from Canada) the Milky Way is brightest and most complex; in the opposite direction, the winter Milky Way is relatively diffuse. This hinted to the German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804), that maybe our Sun is just one star amongst many, together forming a large disk or island universe, and that we lived within it towards its edge. This idea turned out to be essentially correct. Shawn Martin Observing Director RASC, St. John’s Centre Sp Spring in the Northern Hemisphere is a great time to get out and observe galaxies. Let’s learn a bit about what galaxies actually are, how they’re classified, and where to find them in the Springtime Sky.