* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 1st Mississippi Mounted Rifles

Capture of New Orleans wikipedia , lookup

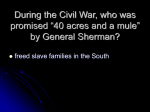

Tennessee in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Wilson's Creek wikipedia , lookup

Border states (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Arkansas in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of New Bern wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Perryville wikipedia , lookup

Georgia in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Namozine Church wikipedia , lookup

Union (American Civil War) wikipedia , lookup

Galvanized Yankees wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Island Number Ten wikipedia , lookup

Cavalry in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of African Americans in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Red River Campaign wikipedia , lookup

Anaconda Plan wikipedia , lookup

Alabama in the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Fort Pillow wikipedia , lookup

Conclusion of the American Civil War wikipedia , lookup