* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Untitled - Cognella Titles Store

Portuguese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Macedonian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sanskrit grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sentence spacing wikipedia , lookup

French grammar wikipedia , lookup

Lexical semantics wikipedia , lookup

Yiddish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Modern Hebrew grammar wikipedia , lookup

Japanese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Kannada grammar wikipedia , lookup

Sloppy identity wikipedia , lookup

Antisymmetry wikipedia , lookup

Focus (linguistics) wikipedia , lookup

Russian grammar wikipedia , lookup

Latin syntax wikipedia , lookup

Polish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Chinese grammar wikipedia , lookup

Construction grammar wikipedia , lookup

Esperanto grammar wikipedia , lookup

English clause syntax wikipedia , lookup

Determiner phrase wikipedia , lookup

Preposition and postposition wikipedia , lookup

Junction Grammar wikipedia , lookup

Pipil grammar wikipedia , lookup

Spanish grammar wikipedia , lookup

Romanian grammar wikipedia , lookup

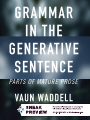

Grammar in the Generative Sentence PARTS OF MATURE PROSE Vaun Waddell Brigham Young University — Idaho FIRST EDITION Bassim Hamadeh, CEO and Publisher Michael Simpson, Vice President of Acquisitions and Sales Jamie Giganti, Senior Managing Editor Jess Busch, Senior Graphic Designer Kristina Stolte, Senior Field Acquisitions Editor Michelle Piehl, Project Editor Alexa Lucido, Licensing Coordinator Allie Kiekhofer, Interior Designer Copyright © 2016 by Vaun Waddell. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information retrieval system without the written permission of Cognella, Inc. First published in the United States of America in 2016 by Cognella, Inc. Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. Cover image copyright © Depositphotos/Neuvector. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-63487-536-3 (pbk) / 978-1-63487-537-0 (br) Contents Preface v 1 | Statements: Clauses and Phrases 1 APPENDIX A: Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address, 4 March 1865 14 APPENDIX B: From Jane Austen’s Sense and Sensibility, Paragraphs 11 and 12 of Chapter XXXVI 16 2 | Parts of Speech: Types of Words APPENDIX C: Word Lists 3 | Rhetoric with Grammar: The Paragraph 19 61 63 APPENDIX D: Strategies 87 APPENDIX E: John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address, Friday 20 January 1961 96 APPENDIX F: Ronald Reagan’s First Inaugural Address, Tuesday 20 January 1981 4 | Independent Clauses: The Base Clause 100 107 APPENDIX G: Abraham Lincoln’s Gettysburg Address, 19 November 1863 127 APPENDIX H: What a Grammarian Knows by Heart 128 5 | Infinite Verbs: Astonishment Unending APPENDIX I: Mark Twain’s Preface to The Tragedy of Pudd’nhead Wilson 6 | Form and Function: Sentence Patterns APPENDIX J: Sentence Diagrams 131 160 163 200 7 | Dependent Clauses: Subordinate, Relative 203 APPENDIX K: Coordinating Conjunctions 231 APPENDIX L: Who/Whom/Whose 233 APPENDIX M: That and Which 234 8 | The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units 237 APPENDIX N: Thomas Hardy, from Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Chapter XIV 258 APPENDIX O: Analysis of Thomas Hardy, from Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Chapter XIV 262 APPENDIX P: Transformed Sentences: Beyond Declarative Indicative 270 9 | Modifiers Restrictive and Nonrestrictive 273 10 | Two Phrases: Participle and Absolute 291 11 | Rhetorical Statistics 317 APPENDIX Q: Analysis of Discourse Units in Kate Chopin, Chapter XVII of The Awakening 323 APPENDIX R: Ralph Waldo Emerson, from “The American Scholar,” First Six Paragraphs of Section III 328 APPENDIX S: George Eliot, from The Mill on the Floss, Book 3, Chapter 5 331 APPENDIX T: Thomas Hardy, from Tess of the d’Urbervilles, Chapter L 334 APPENDIX U: Kate Chopin, from The Awakening, Chapter XVII 337 12 | Punctuating Discourse Units 341 13 | Practice Tests and Answers 347 Preface Grammar in the Generative Sentence addresses the question, “How does language work?” It is not a compilation of a bunch of rules and exceptions to rules. Most languages have relatively respectable grammars. English is a language beautiful and powerful; it is nevertheless grammatically muddy. Its origins and instincts are German, but history has made its scholastic manners Latin and its clinical customs Greek. History also has given a Latin legacy to the study of English and the usual ways of talking about it. With this mongrel pedigree, English doesn’t follow a single set of grammatical patterns. And a rule with exceptions is not really a rule. Trying to sort English grammar out is a time-tested exercise in frustration and, for generation upon generation of fidgeting pupils, futility. Grammar in the Generative Sentence offers a model of English drawn from practice of some of its best practitioners. It is an introduction for undergraduate students anticipating entrance to the professional world as writers, readers, teachers, and editors. Its scope is one semester. Its purposes are to illustrate language well written in our times and to empower its students with the grammatical underpinnings of our language as it works. ——What does it take to employ grammar? This book posits five imperatives. Parts of Speech Verbs Form and Function Sentence Patterns Clauses and Phrases v These five are prerequisite to a workable grammar, and each item is prerequisite to what comes after it. Grammar in the Generative Sentence sets forth these five features of language through explanation, example, and exercise. The bond between grammar and rhetoric is indissoluble. Grammar in the Generative Sentence is interested in how clauses and phrases are assembled and how they are combined into rhetorically stunning prose. Its sample texts are from language in print, emphasizing grammatical understanding and rhetorical skill side by side, with minimal resort to contrived examples. Studying grammar does not necessarily lead to better writing—in fact, the grammar course is often sundered from practical applications, writing foremost among them. Grammar in the Generative Sentence is not a text on writing, but it culminates in a statistical summary of what real writers really do with grammar, with the conclusion that command of the five imperatives listed above is a necessary if not sufficient condition for good writing, along with performance within ranges of rhetorical use revealed in simple statistics. The discourse unit—a statement in the form of a clause or a phrase—is the essential unit of prose, and the generative sentence—a sentence containing multiple statements—is far more widespread and significant than traditional grammars recognize. A grammar that analyzes sentences only in terms of clauses leaves very much of its work undone. Samples surveyed in Chapter 11 show that: Consistent with current instruction, statements are short (about ten words)—but— Sentences are long, averaging well over twenty words, and More than 40 percent of statements are not independent clauses. Most grammar instruction stops short of describing English prose as it actually shows up on the page. A study that divorces rhetoric from grammar and then fails to recognize more than one third of the statements in print cannot be very useful, and it cannot command credence of the students compelled through it. This book tries to step closer to language as it works. ——- vi | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose Sean’s teacher sent home a note asking that we review with him the multiplication tables. Sitting down with my third grader, I noted that he had a general understanding of the numbers but wasn’t proficient and didn’t care. This story replayed three times, so I asked him what he was thinking. He explained: You know how the teacher is always starting into a new subject with lots of excitement, but after a couple of weeks she moves on to a new subject? These times tables don’t interest me, so I’m going to sit them out and wait for the teacher to get excited about something else. Nothing wrong with the boy’s understanding of the system, but his error was now evident. “Oh!” I said, “That makes sense, but with the times tables it’s different. They are not going anywhere; you will need them forever.” This put an end to the necessity of drilling him on 3 × 7 = 21, and the notes from the teacher stopped coming. Grammar is not going anywhere. Productive action in our world (maybe not the best of all possible worlds, but our world still) relies on competence with the great symbol systems—language or math or both. Let’s put forth our hands together and grasp the grammar. ——Knowing grammar gives you power over language rather than leaving language in power over you. Every little child knows grammar—without which intelligible utterance is not possible. Studying grammar might introduce to you concepts you don’t already know, or it might not. It is possible that you already know intuitively just about all that grammar allows. Mostly, studying grammar brings to a conscious level that which you already know at an intuitive level. It means taking conscious control. It means preparing to act deliberately and with purpose. Rhetoric is selling. We are all saleswomen and men. Communication includes the message, but also the audience and the purpose. These three comprise the rhetorical field wherein language works. Whether your specialty is scientific, legal, technical, athletic, businesslike, educational, social, political—or whatever else—controlling your future depends on controlling language. Preface | vii Rhetoric is about what is desirable and effective, about results. Grammar is about what is possible; it is prerequisite to rhetoric, prerequisite for putting language to work in its rhetorical field of message, purpose, and audience. How many fretful schoolchildren have evaded learning grammar, excused by the teacher‘s saying that grammar helps avoid mistakes? That is weak salesmanship: how many schoolchildren, not to say university students, anticipate a future that calls for conscious, competent use of (more or less) formal written language? It is hard to see ahead of time that conscious knowledge of grammar is positive power, the power to act effectively, even decisively, in one’s chosen rhetorical field. ——Thank you for looking at Grammar in the Generative Sentence. Could it be that you break your brain mastering its theoretical and practical lessons, then hold it fast as I hold onto a handful of my undergraduate texts—precious helpers of a lifetime, mementos of empowered living? viii | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose CHAPTER EIGHT The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units With what is covered so far, plus nonrestrictive phrases, a grammarian can analyze the world’s best English prose without apology. The top rank of prose includes such as: Abraham Lincoln’s Second Inaugural Address: Appendix A John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address: Appendix E Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles: An excerpt from Chapter XIV appears in Appendix N, at the end of this chapter; Appendix O repeats the excerpt and identifies forms in it as well as underlining the words that reveal the forms. In clauses, such words are subject and verb with tense; in phrases they are headwords. More than for any other reason, Grammar in the Generative Sentence exists because of the traditional divorcement of rhetoric from grammar, most apparent in grammarians’ resolute shunning of nonrestrictive phrases. This is strange, because nowhere is the magnificence of magnificent prose more apparent than in nonrestrictive phrases. Necessary conditions of superb prose are a blend of brief statements to set down generalities, nonrestrictive modifiers to explain them, and an unpretentious rhetoric, perhaps even slightly understated. 237 Rhetoric has sometimes grotesquely overwhelmed content. At Gettysburg, Mr. Lincoln’s remarks were preceded by a harangue from Edward Everett, an orator in a time when everyone did not consider the very word “oration” grating. His 13,607-word speech kicked off: Standing beneath this serene sky, overlooking these broad fields now reposing from the labors of the waning year, the mighty Alleghenies dimly towering before us, the graves of our brethren beneath our feet, it is with hesitation that I raise my poor voice to break the eloquent silence of God and Nature. But the duty to which you have called me must be performed;—grant me, I pray you, your indulgence and your sympathy. A couple of hours later, he wrapped up: But they, I am sure, will join us in saying, as we bid farewell to the dust of these martyr-heroes, that wheresoever throughout the civilized world the accounts of this great warfare are read, and down to the latest period of recorded time, in the glorious annals of our common country, there will be no brighter page than that which relates the Battles of Gettysburg. People in those days got more practice listening than most of us get nowadays, but whatever else can be said of Mr. Everett, he is forgettable. Two lessons about language are that, (1) if you think fuzzily and indulge in overstatement, you won’t be thanked, and (2) lots of style with little substance may get it for you on the fashion runway, but in language it invites ridicule. The eloquent silence of God and Nature is immeasurably better. English teachers may fall off one side or the other of the knife’s edge, over-promoting style or inveighing against it. Students avoid style because they can’t control it. But if content is at level nine on the ten-point scale, style at level eight is still understated and can be, oh, so precious. Balanced with content, style is the right thing. Imbalance has earned “rhetoric” a bad name; the word connotes a range of meanings from “fluff” to “lies.” It needs to return to its Aristotelian meaning: language desirable and effective. A generative sentence is one with an independent clause, or base clause (BC), and at least one nonrestrictive element. Grammatically, a nonrestrictive element is a dependent clause or a phrase. Phrases and dependent clauses are spoken of in previous 238 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose pages, primarily in restrictive use. In this chapter, emphasis is on their nonrestrictive use. Nonrestrictive use refers to statements that supplement the main statement of the sentence, the base clause, which is grammatically complete in itself without the nonrestrictive elements. Nonrestrictive elements are grammatically dependent (being phrases and dependent clauses) but logically complete as statements, at least by implication. Grammatically, a nonrestrictive element is one that is not essential to the meaning of its superordinate unit but adds information, implying a separate statement and answering a different question. Nonrestrictive elements are punctuated separately. Functions remain unchanged: the four large ones—nominal, adjectival, verbal, adverbial—and four that are relatively specific—pronominal, prepositional, conjunctive, appositive. “Discourse unit” (DU) is a term useful in the discussion of generative sentences. A DU is a statement in the form of a clause or a phrase. The most general division among DUs is to separate independent clauses from nonrestrictive elements, which are in the form of dependent clauses and phrases. The next division is between the dependent clauses and the phrases. A phrase is any DU lacking any of the three necessities of a clause: subject, verb, and verb tense. Free modifier (FM) is a convenient term for a nonrestrictive element. For speaking of the generative sentence, here is a vocabulary: Generative sentence—a sentence consisting of more than one discourse unit Discourse unit (DU)—a clause or phrase making a statement and punctuated separately Base clause (BC)—an independent clause, necessary to make a sentence Free modifier (FM)—a phrase or dependent clause in nonrestrictive use Cumulative sentence—a generative sentence made by combining sentences Any FM can be grammatically expanded into an independent clause by adding information that is known though not stated. The logical completeness of the FM makes possible this expansion in a process which is the reverse of sentence combining. A generative sentence is structurally similar to a paragraph—it is an idea explained. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 239 Exercise 8.1: Sentence Dis-combining Make each DU a simple sentence, using only information already present in the text. Sentences are adapted from Ronald Reagan’s First Inaugural Address. (In lines d and e, you may notice that Mr. Reagan evoked the grand setting of his speech, as Mr. Everett had done at Gettysburg. But Mr. Reagan used understated rhetoric, not Mr. Everett’s huffy-puffy stuff.) a. The economic ills will go away because we, as Americans, have the capacity now, as we have had in the past, to do whatever needs to be done to preserve this last and greatest bastion of freedom. The economic ills will go away because we have the capacity now to do whatever needs to be done to preserve this great bastion of freedom. We have this capacity as Americans. We have had this capacity in the past. b. With the idealism and fair play which are the core of our system and our strength, we can have a strong and prosperous America, at peace with itself and the world. c. Now, so there will be no misunderstanding, it’s not my intention to do away with government. It is, rather, to make it work—work with us, not over us; to stand by our side, not ride on our back. 240 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose d. Directly in front of me, the monument to a monumental man, George Washington, father of our country, a man of humility who came to greatness reluctantly. e. Beyond those monuments to heroism is the Potomac River, and on the far shore the sloping hills of Arlington National Cemetery, with its row on row of simple white markers bearing crosses or Stars of David. f. The crisis we are facing today does require, however, our best effort and our willingness to believe in ourselves and to believe in our capacity to perform great deeds, to believe that together, with God’s help, we can and will resolve the problems which now confront us. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 241 A generative sentence follows from a method of thought wonderful but simple. An unchanging factor is the rhetorical field, consisting of message, purpose, and sense of audience (Chapter 3). Here is a step-by-step way to begin to think generatively. Write the sentence, the BC. End it with a comma, not a period. Ask, “Given my rhetorical field, what other questions need answering?” Think structurally as in writing a paragraph. Answer the questions with free modifiers, more often phrases than dependent clauses. FMs create certain potentials for the generative writer. The writer’s mind becomes more active and more attuned to audience and purpose. Relationships among statements can be closer and clearer than across a sentence break. Thoughts can be thought that are not otherwise thinkable. This could be considered an overstatement, but experience demonstrates that, with levels of generality and a full repertoire of FMs, thoughts do occur that otherwise would and could not. With FMs, language can sometimes express what otherwise cannot be expressed. Prior knowledge of parts of speech, verbs, form and function, and sentence patterns makes learning nonrestrictive DUs possible, even easy. Mechanically, a nonrestrictive DU is one that is punctuated separately and is subordinate, at some level, to a base clause in the same sentence with it. Each sample sentence below contains one base clause, making the more general assertion of the sentence, and one FM underlined. Sentences are adapted from Book Second, Chapter 1, of George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss. Tom had a large share of pride, which had found itself very comfortable in the world. Stated: Tom had a large share of pride. Implied: Tom’s pride had found itself very comfortable in the world. Form of FM: Relative Clause 242 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose He, Tom Tulliver, appeared uncouth and stupid. Stated: He appeared uncouth and stupid. Implied: He was Tom Tulliver. Form of FM: Appositive As his prayers were learned by heart, he shrank from introducing an extempore passage. Stated: He shrank from introducing an extempore passage. Implied: His prayers were learned by heart. Form of FM: Subordinate Clause Mr. Stelling, convinced that this must be carelessness, had lectured him very seriously. Stated: Mr. Stelling had lectured him very seriously. Implied: Mr. Stelling was convinced that this must be carelessness. Form of FM: Past Participle Phrase Mr. Stelling lectured him, pointing out that he must not fail to seize the opportunity. Stated: Mr. Stelling lectured him. Implied: Mr. Stelling pointed out that he must not fail to seize the opportunity. Form of FM: Participle Phrase Tom, more miserable than usual, determined to try his sole resource. Stated: Tom determined to try his sole resource. Implied: Tom was more miserable than usual. Form of FM: Adjective Phrase He added, in the same low whisper, “And please to make me remember my Latin.” Stated: He added, “And please to make me remember my Latin.” Implied: He added it in the same low whisper. Form of FM: Prepositional Phrase He spent a dull, lonely evening, preparing his lessons for the morrow. Stated: He spent a dull, lonely evening. Implied: He prepared for his lessons for the morrow. Form of FM: Participle Phrase The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 243 His eyes were apt to get dim over the page—though he hated crying. Stated: His eyes were apt to get dim over the page. Implied: He hated crying. Form of FM: Subordinate Clause By now some principles have made themselves apparent. Ordinary (though well written) prose includes a high incidence of FMs. Phrases are as expressive and informative as dependent clauses. Information in any FM is perfectly clear and complete, implying a full statement. Nonrestrictive information is increasingly specific, and levels of specificity are more clear to read when the specific statement is given in grammatically different form than the general statement. Because an FM gives information that is subordinate to what is in the modified unit, it is good to not present the subordinate information in a grammatically coordinate element, such as in a separate sentence. Furthermore, strategies are more nearly explicit when added information is in an FM than when it is in a separate sentence, partly because the FM is more proximate to the statement modified, partly because strategic words are more likely to be included. In meaning, the nonrestrictive information may be so closely tied to the modified unit that placing it in a separate sentence becomes over-explicit, even silly, as in, “He appeared stupid and uncouth. He was Tom Tulliver.”—a method of addition from elementary school. 244 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose The text is shorter (with repetitions removed) and more rhetorically mature with the FM than with implied BCs written out. So the best opportunity to attain careful specificity in rhetorically mature prose is by means of FMs. A sentence with several FMs becomes structurally and strategically similar to a paragraph. The power of Mr. Lincoln’s and Mr. Hardy’s prose, as with Ms. Eliot’s and Ms. Austen’s, is a quantifiable result of gripping content coupled with a balance of simple and generative sentences. Chapters 9–11 address the quantification; this chapter emphasizes the nonrestrictive phrase. What complaints are set out against generative sentences? That they accrue mechanical errors when writers lack control of discourse units, that, when writers acquire discourse units, style can outrun content, and that generative sentences are long. Poppycock. A sentence cannot be too long if its DUs are crisp and its structure and strategies clear. Declaring a writer’s education complete short of mastering DUs makes writing the only athletic event where players are coached to ignore the basics. Decades ago it was established that studying grammar does not improve writing. But finding out the grammar of discourse units and rhetorical principles, and knowing one’s content: these can be applied so as to achieve quantum improvement in writing. Without them, writing will not improve regardless of what else is learned. They are necessary if not sufficient causes of powerful prose. A phrase lacks something from among the three essentials of a clause: subject, verb, and verb tense. What is unsaid in a nonrestrictive phrase, that would make it an independent clause, is revealed elsewhere in the sentence or the passage. As the clause has its three essentials, so the phrase has its identity marker—a headword. To learn a phrase’s form, find the headword and determine its part of speech. Looking from within the phrase, the headword is the superordinate word in the phrase, the most general of all the words. Looking at the phrase from the outside in, the headword is the word that connects the phrase with its superordinate unit. The headword is visible at the top of a diagram of the phrase. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 245 Exercise 8.2: Finding Headwords (1) Make a sentence diagram for each FM. No need here to diagram BCs. (2) The word that leads off a sentence diagram is the headword. Label it by its part of speech. Sentences are adapted from Book Second, Chapter 1 of George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss. a. He could acquire Mr. Stelling’s approbation, by any voluntary action of that sort. by action of vo at th ry ta lun y an sort b. Mr. Stelling, convinced that this must be carelessness, had lectured him very seriously. c. Mr. Stelling lectured him, pointing out that he must not fail to seize the opportunity. 246 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose d. Tom, more miserable than usual, determined to try his sole resource. e. He added, in the same low whisper, “And please to make me always remember my Latin.” f. He spent a dull, lonely evening, preparing his lessons for the morrow. g. Yap, ready to obey the least sign, would come before him in a sort of calenture. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 247 The total number of DUs permitted by English grammar is eleven. They are forms, not functions. Three DUs are clauses, the familiar independent clause and its dependent friends, subordinate and relative clauses. Eight DUs are phrases, divided three each to nouns and verbs, and one each to adjective and adverb. The three verbid phrases follow the three infinite forms: infinitive, participle, and past participle. Unsurprisingly, the past participle phrase overlaps with the adjective phrase. Adjective and adverb phrases have headwords that are adjectives and adverbs. This is not mysterious. Noun phrases include the unspecified noun phrase, almost always used in apposition, and the prepositional phrase, which, you recall, adapts a nominal for adjectival or adverbial use. The world could wag merrily on without Grammar in the Generative Sentence challenging tradition by saying that what is clearly a prepositional phrase is at the same time a noun phrase. Doesn’t the noun becoming the object of the preposition make the object subordinate to the preposition? Grammatically, we can say that the object is subordinate to the preposition, but logically this is not so. The preposition adapts its object for adjectival or adverbial function and indicates a strategic relationship between the prepositional phrase and what it modifies, but the message of modification is carried by the object of the preposition, the nominal. Rationales for classifying a prepositional phrase as a type of noun phrase are to emphasize the value of the object of the preposition as a modifier, to clarify the prepositional function, and to call attention to the strategy at work between the prepositional phrase and the element it modifies. The eighth phrasal discourse unit, completing the list of noun phrases, has a mouthful of a name, is easy to learn while being both beautiful and potent in prose, and is known by almost no one, including a fair share of English teachers. It is nevertheless known by the least of writers who can or ought to be called writers. The one student in my 35-year teaching acquaintance (up until now), who explained to me the nominative absolute phrase before I explained it to her, was Liliya, a Tatar girl from the pedagogical institute in Arsk who had the habit of paying attention. It was worth living a year in Kazan to know her. Often called an absolute (no connection with vodka), it has a subject and a predicate, but its predicate is less than the predicate of a clause—it has only an infinite verb or no verb at all. A predicate comes after a subject (in standard word order) and says something about it. “Subject” here means complete subject—the simple subject with its whole entourage of adjectives, adjectival phrases, clauses, and appositives, just like a First Lady on vacation. In most cases, if “was” or “were” is added to the predicate of an absolute, the 248 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose phrase becomes an independent clause. Having a subject and a predicate, an absolute demonstrates a sentence pattern, with “was” or “were” added as a linking verb if needed to illustrate the clause implied by the absolute phrase. The glad tiding of the absolute phrase is that a statement can be made about a subject, not only without verb tense but without any verb at all. In the absolute, we can feel the pure and paradoxical exultation of nonverbal being. Would an example or two help? Mr. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address is notable for delicate rhetorical restraint and studied brevity of expression—grand ideas stated simply. At one point a series of absolutes serves his purpose. But neither can two great and powerful groups of nations take comfort from our present course— both sides overburdened by the cost of modern weapons, both rightly alarmed by the steady spread of the deadly atom, yet both racing to alter that uncertain balance of terror that stays the hand of mankind’s final war. Or from the ordinary course of narration in Mr. Hardy’s extraordinary Tess, chapters XLV and XLVI. Now he wore neatly trimmed, old-fashioned whiskers, the sable moustache having disappeared. They moved onward together, she with unwilling tread. It was two horses and a man, the plough going between them, turning up the cleared ground for a spring sowing. She did not answer, and he watched her inquiringly, as with bent head, , she resumed her trimming of the swedes. ^ her face completely screened by the hood Tess did no more than listen, throwing down one globular root and taking up another with automatic regularity, ^ the pensive contour of the mere fieldwoman alone marking her. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 249 How strange it is that so few dare write these—while no one thinks anything at all of reading them. By method of modification, absolutes separate into two classes. Sometimes they comment on a specific referent in the statement modified; sometimes they remark on the environment or general context of the statement modified, the broad reference modification introduced in Chapter 7. Mr. Kennedy specifies his “two great and powerful groups of nations” with the resounding “both.” Mr. Hardy, in the first of his sentences quoted, makes “whiskers” the referent of “moustache,” and in the second sentence, “they” is the referent of “she.” But in the third of Hardy’s sentences, the plough is a contextual or environmental factor separate from the horses and the man. Sometimes, for rhetorical purposes, an absolute is introduced by “with.” The underlined part of “Millie rushed into the room with scraps of paper fluttering in her wake” is correctly identified as a prepositional phrase, but more usefully identified as an absolute phrase. The preposition “with” has a dictionary meaning, suggesting a strategy of accompaniment. When it introduces an absolute phrase whose meaning is the same with or without the “with,” then it is better to ignore “with” as a preposition and identify the phrase as an absolute. In the absolute phrase introduced by “with,” “with” has only the approximate meaning of a comma. Replacing a potential comma, “with” smooths the rhetorical rhythm of the utterance without actually imposing the strategic prepositional meaning of “with” upon the utterance. Since “appositive” names a function and “absolute” names a form, an absolute phrase can function appositively, though this does not happen often. An example: “Mike, Molly’s son wearing the paperbag, delivers 120 newspapers each morning.” 250 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose Exercise 8.3: Nominative Absolute Phrases (1) Place parentheses around each absolute. Underline its simple subject. Circle its verb, if any. (2) Note whether each absolute modifies a referent (Referent) in another DU or contextualizes (Context) by broad reference. Sentences are adapted from chapters XL–XLII of Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles. a. b. c. d. e. f. g. referent to “to call” It was necessary for him to call at theWellbridge farm-house, in which he had spent withTess the first three days of their marriage, the trifle of rent having to be paid, the key given up of the rooms they had occupied, and two or three small articles fetched away that they had left behind. referent to “they” They sped along eastward for some considerable distance, Izz making no observation. ________________ After again leaving Marlott, her home, she had got through the spring and summer without any great stress upon her physical powers, the time being mainly spent in rendering light irregular service at dairy-work near Port-Bredy to the west of the Blackmoor Valley, equally remote from her native place and from Talbothays. ________________ Tess had thirty pounds coming to her almost immediately from Angel’s bankers, and, the case being so deplorable, as soon as the sum was received she sent the twenty as requested. ________________ Tess went onward with fortitude, her recollection of the birds’ silent endurance of their night of agony impressing upon her the relativity of sorrows and the tolerable nature of her own, if she could only rise high enough to despise opinion. ________________ Her object being a winter’s occupation and a winter’s home, there was no time to lose. ________________ Thus she went forward from farm to farm in the direction of the place whence Marian had written to her, which she determined to make use of as a last shift only, its rumoured stringencies being the reverse of tempting. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 251 That was a brief and narrow introduction to the absolute. Chapter 10 is devoted to it and the participle phrase. Here are the eleven discourse units on a tree diagram, a tree without a partridge, and no twelfth drummer within earshot. DUs clauses 1 independent (base clause) 2 subordinate clause phrases dependent clause 3 relative clause 4 prepositional phrase noun phrase 5 unspecified noun phrase (most often appositive, but not always) 6 7 adjective nominative absolute phrase verb phrase 9 8 infinitive phrase present participle phrase 11 adverb 10 past participle phrase The only DUs not yet discussed in nonrestrictive use are adjective and adverb phrases. As FMs, they are manifest as a single adjective or adverb, a pair or a cluster of either, a phrase with the one or the other as headword, or some combination of these three. The past participle, adjectival when not in a nominal or verbal phrase, works like an adjective except that it can take an object or complement, being by form a verb. Whether to punctuate an adjective or adverb phrase restrictively or as an FM is often at the discretion of the writer. Sometimes a single adjective or adverb is used nonrestrictively to emphasize it. Sometimes the adjective or adverb phrase is long, or the logic of the sentence recommends that it be an FM. Adverbs are more likely to be used as FMs than adjectives, owing to their ability to alight in varied locations. 252 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose Exercise 8.4: Adjective and Adverb Phrases as FMs (1) Underline each adjective or adverb FM. (2) Circle the headword of each. (3) Note whether adjective (Adj) or adverb (Adv). past participle or a. adjective Delighted with her test results, Millie decided to apply for a promotion. b. ________ Millie stayed in bed, ill from overwork. c. ________ Daily and deeply overworked, Millie considered looking for a different job. d. ________ Molly, anxious to keep Millie on, hired her an assistant. e. ________ Molly’s goldfish floated belly-up at the top of the water—dead. f. ________ As guiltily as if she had a human conscience, the cat looked up at Molly. g. ________ Amazingly, Millie finished the balance sheet a day early. h. ________ The paper was unreadable, torn in several places and smudged past recognition. i. ________ Millie requested a new copy, not immediately but the next day. j. ________ When worn to less than a 3/8” diameter, the bolt needs to be replaced. Diagramming generative sentences is complex and needs space. It requires identifying each DU and restrictive dependent clause, determining their forms and functions, and then following the diagram’s arbitrary patterns. A modifier is diagrammed the same whether restrictive or an FM. Some FMs have no single point of connection with their superordinate unit, but modify it in a holistic way, the modifiers of broad reference. These are often vaguely adverbial, more likely to answer the question “how” than any other— but no single rule explains all the possibilities. Some of this sort can be connected by a dotted line upward to a verb, if a verb is present in their superordinate unit. Anyway, the diagram is not an end in itself but an illustration of understanding the five grammatical imperatives. An explanation based on knowledge of the five is a good explanation; and such a diagram, a good diagram. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 253 Exercise 8.5: Analyze and Diagram Generative Sentences (1) Using numbers and lines, draw a tree diagram showing structure in the sentence. (2) Diagram the sentence. Sentences comprise the first paragraph of Book Sixth, Chapter 7, of George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss. a. 1 The next morning was very wet—2the sort of morning 3aon which male neighbors 4who have no imperative occupation at home 3bare likely to pay their fair friends an illimitable visit. (3) 1 neighbors are pay sort morning ( ) of e th (1) morning was wet y ver t nex The 254 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose ble (2) r ir e tiv 4 fai the at home era imp no 3 friends ita occupation visit illim have which an who to le on ma 2 (4) likely b. 1a The rain, 2which has been endurable enough for the walk or ride one way, 1bis sure to become so heavy and at the same time so certain to clear up by and by, 3that nothing but an open quarrel can abbreviate the visit; 4latent detestation will not do at all. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 255 c. And 1if people happen to be lovers, 2awhat can be so delightful—3in England—2bas a rainy morning? d. 1 English sunshine is dubious: 2bonnets are never quite secure; and 3if you sit down on the grass, 4it may lead to catarrhs. But 5the rain is to be depended on. [Diagram as one sentence.] 256 | Grammar in the Generative Sentence: Parts of Mature Prose e. 1 You gallop through it in a mackintosh and presently find yourself in the seat 2you like best—3a little above or a little below the one 4on which your goddess sits—(5it is the same thing to the metaphysic mind, and 6that is the reason 7why women are at once worshipped and looked down upon)—8with a satisfactory confidence 9that there will be no lady-callers. The Generative Sentence: Discourse Units | 257