* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Seasonal affective disorder

Classification of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

Panic disorder wikipedia , lookup

Mental disorder wikipedia , lookup

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders wikipedia , lookup

Schizoaffective disorder wikipedia , lookup

Postpartum depression wikipedia , lookup

Bipolar II disorder wikipedia , lookup

Dissociative identity disorder wikipedia , lookup

Conversion disorder wikipedia , lookup

Child psychopathology wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Narcissistic personality disorder wikipedia , lookup

Psychedelic therapy wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Generalized anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

Separation anxiety disorder wikipedia , lookup

History of mental disorders wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Major depressive disorder wikipedia , lookup

Behavioral theories of depression wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Treatments for combat-related PTSD wikipedia , lookup

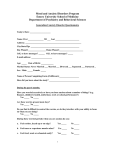

Seasonal affective disorder From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The examples and perspective in this article deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. Please improve this article and discuss the issue on the talk page. (January 2011) Bright light therapy is a common treatment for seasonal affective disorder and for circadian rhythm sleep disorders. Seasonal affective disorder (SAD), also known as winter depression, winter blues, summer depression, summer blues, or seasonal depression, is a mood disorder in which people who have normal mental health throughout most of the year experience depressive symptoms in the winter or summer,[1] spring or autumn year after year. In the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), SAD is not a unique mood disorder, but is "a specifier of major depression".[2] Although experts were initially skeptical, this condition is now recognized as a common disorder, with its prevalence in the U.S. ranging from 1.4 percent in Florida to 9.7 percent in New Hampshire.[3] The U.S. National Library of Medicine notes that "some people experience a serious mood change when the seasons change. They may sleep too much, have little energy, and may also feel depressed. Though symptoms can be severe, they usually clear up."[4] The condition in the summer can include heightened anxiety.[5] SAD was formally described and named in 1984 by Norman E. Rosenthal and colleagues at the National Institute of Mental Health.[6][7] There are many different treatments for classic (winter-based) seasonal affective disorder, including light therapy with sunlight or bright lights, antidepressant medication, cognitive-behavioral therapy, ionized-air administration,[8] and carefully timed supplementation of the hormone melatonin.[9] Contents [hide] 1 Symptoms 2 Diagnostic criteria 3 Physiology 4 History 5 Origin 6 Treatment 7 Incidence o 7.1 Nordic countries o 7.2 Other countries 8 SAD and bipolar disorder 9 Role of Occupational Therapy in Treating SAD o o 9.1 Biomedical approaches 9.1.1 Light Therapy 9.1.1.1 Effectiveness 9.1.2 Antidepressant Medications (Pharmacotherapy) 9.2 Psychosocial approaches to SAD interventions 9.2.1 Group Therapy 9.2.2 Cognitive Behavioural Therapy 9.2.3 Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) 9.2.4 Behavioural activation 9.2.5 Problem-solving therapies 9.2.6 Positive psychotherapy 9.2.7 Self-System Therapy 9.2.8 Outdoor therapy o 9.3 Assessments for SAD 10 See also 11 External links 12 References 13 External links Symptoms Symptoms of SAD may consist of difficulty waking up in the morning, morning sickness, tendency to oversleep and over eat, especially a craving for carbohydrates, which leads to weight gain. Other symptoms include a lack of energy, difficulty concentrating on or completing tasks, and withdrawal from friends, family, and social activities and decreased sex drive.[citation needed] All of this leads to the depression, pessimistic feelings of hopelessness, and lack of pleasure which characterize a person suffering from this disorder.[citation needed] People who experience spring and summer depression show symptoms of classic depression including insomnia, anxiety, irritability, decreased appetite, weight loss, social withdrawal, decreased sex drive,[5] and suicide. Diagnostic criteria According to the American Psychiatric Association DSM-IV criteria,[10] Seasonal Affective Disorder is not regarded as a separate disorder. It is called a "course specifier" and may be applied as an added description to the pattern of major depressive episodes in patients with major depressive disorder or patients with bipolar disorder. The "Seasonal Pattern Specifier" must meet four criteria: depressive episodes at a particular time of the year; remissions or mania/hypomania at a characteristic time of year; these patterns must have lasted two years with no nonseasonal major depressive episodes during that same period; and these seasonal depressive episodes outnumber other depressive episodes throughout the patient's lifetime. The Mayo Clinic[5] describes three types of SAD, each with its own set of symptoms. In the popular culture, sometimes the term "seasonal affective disorder" is applied inaccurately to the normal shift to lower energy levels in winter, leading people to believe they have a physical problem that should be addressed with various therapies or drugs.[11] Physiology Seasonal mood variations are believed to be related to light. An argument for this view is the effectiveness of bright-light therapy.[12] SAD is measurably present at latitudes in the Arctic region, such as Finland (64°00′N) where the rate of SAD is 9.5%.[13] Cloud cover may contribute to the negative effects of SAD.[14] The symptoms of SAD mimic those of dysthymia or even major depressive disorder. There is also potential risk of suicide in some patients experiencing SAD. One study reports 6-35% of sufferers required hospitalization during one period of illness. [14] At times, patients may not feel depressed, but rather lack energy to perform everyday activities.[12] Various proximate causes have been proposed. One possibility is that SAD is related to a lack of serotonin, and serotonin polymorphisms could play a role in SAD,[15] although this has been disputed.[16] Mice incapable of turning serotonin into N-acetylserotonin (by Serotonin N-acetyltransferase) appear to express "depression-like" behavior, and antidepressants such as fluoxetine increase the amount of the enzyme Serotonin N-acetyltransferase, resulting in an antidepressant-like effect.[17] Another theory is that the cause may be related to melatonin which is produced in dim light and darkness by the pineal gland, since there are direct connections, via the retinohypothalamic tract and the suprachiasmatic nucleus, between the retina and the pineal gland. Subsyndromal Seasonal Affective Disorder is a milder form of SAD experienced by an estimated 14.3% (vs. 6.1% SAD) of the U.S. population.[18] The blue feeling experienced by both SAD and SSAD sufferers can usually be dampened or extinguished by exercise and increased outdoor activity, particularly on sunny days, resulting in increased solar exposure.[19] Connections between human mood, as well as energy levels, and the seasons are well documented, even in healthy individuals.[citation needed] Mutation of a gene expressing melanopsin has been implicated in the risk of having Seasonal Affective Disorder.[20] History SAD was first systematically reported and named in the early 1980s by Norman E. Rosenthal, M.D., and his associates at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Rosenthal was initially motivated by his desire to discover the cause of his own experience of depression during the dark days of the northern US winter. He theorized that the lesser amount of light in winter was the cause. Rosenthal and his colleagues then documented the phenomenon of SAD in a placebo-controlled study utilizing light therapy.[6][7] A paper based on this research was published in 1984. Although Rosenthal's ideas were initially greeted with skepticism, SAD has become well recognized, and his 1993 book, Winter Blues[21] has become the standard introduction to the subject.[22] Research on SAD in the United States began in 1970 when Herb Kern, a research engineer, had also noticed that he felt depressed during the winter months. Kern suspected that scarcer light in winter was the cause and discussed the idea with scientists at the NIMH who were working on bodily rhythms. They were intrigued, and responded by devising a lightbox to treat Kern’s depression. Kern felt much better within a few days of treatments, as did other patients treated in the same way.[7] Origin In many species, activity is diminished during the winter months in response to the reduction in available food and the difficulties of surviving in cold weather. Hibernation is an extreme example, but even species that do not hibernate often exhibit changes in behavior during the winter. It has been argued that SAD is an evolved adaptation in humans that is a variant or remnant of a hibernation response in some remote ancestor.[23] Presumably, food was scarce during most of human prehistory, and a tendency toward low mood during the winter months would have been adaptive by reducing the need for calorie intake. The preponderance of women with SAD suggests that the response may also somehow regulate reproduction.[23] Treatment One type of light therapy lamp There are many different treatments for classic (winter-based) seasonal affective disorder, including light therapy, medication, ionized-air administration, cognitive-behavioral therapy and carefully timed supplementation[24] of the hormone melatonin. Photoperiod-related alterations of the duration of melatonin secretion may affect the seasonal mood cycles of SAD. This suggests that light therapy may be an effective treatment for SAD.[25] Light therapy uses a lightbox which emits far more lumens than a customary incandescent lamp. Bright white "full spectrum" light at 10,000 lux, blue light at a wavelength of 480nm at 2,500 lux or green (actually cyan or blue-green [26]) light at a wavelength of 500nm at 350 lux are used, with the first-mentioned historically preferred.[27][28] Bright light therapy is effective[18] with the patient sitting a prescribed distance, commonly 30–60cm, in front of the box with her/his eyes open but not staring at the light source [13] for 30–60 minutes. A 1995 study showed that 500 nm cyan light therapy at doses of 350 lux produces melatonin suppression and phase shifts equivalent to 10,000 lux bright light therapy in winter depressives.[27] However, in this study, the improvement in depression ratings did not reach statistical significance. A study published in May 2010 suggests that the blue light often used for SAD treatment should perhaps be replaced by green or white illumination.[29] Discovering the best schedule is essential. One study has shown that up to 69% of patients find lightbox treatment inconvenient and as many as 19% stop use because of this.[13] A study from a company in Finland has shown that bright light therapy delivered directly to photosensitive regions of the brain via the ear canal may also be an effective alternative to light box treatment. In studies without control groups 92% of SAD sufferers experienced total relief from their symptoms when receiving bright light treatment in this way. [30][unreliable source?] Dawn simulation has also proven to be effective; in some studies, there is an 83% better response when compared to other bright light therapy.[13] When compared in a study to negative air ionization, bright light was shown to be 57% effective vs. dawn simulation 50%.[8] Patients using light therapy can experience improvement during the first week, but increased results are evident when continued throughout several weeks.[13] Most studies have found it effective without use year round but rather as a seasonal treatment lasting for several weeks until frequent light exposure is naturally obtained.[12] Light therapy can also consist of exposure to sunlight, either by spending more time outside[31] or using a computer-controlled heliostat to reflect sunlight into the windows of a home or office.[32][33] SSRI (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor) antidepressants have proven effective in treating SAD. Bupropion is also effective as a prophylactic.[14] Effective antidepressants are fluoxetine, sertraline, or paroxetine.[12][34] Both fluoxetine and light therapy are 67% effective in treating SAD according to direct head-to-head trials conducted during the 2006 Can-SAD study.[35] Subjects using the light therapy protocol showed earlier clinical improvement, generally within one week of beginning the clinical treatment.[12] Negative air ionization, which involves releasing charged particles into the sleep environment, has been found effective with a 47.9% improvement if the negative ions are in sufficient density (quantity).[36][37][38] Depending upon the patient, one treatment (e.g., lightbox) may be used in conjunction with another (e.g., medication).[12] Modafinil may be an effective and well-tolerated treatment in patients with seasonal affective disorder/winter depression.[39] Alfred J. Lewy of Oregon Health & Science University and others see the cause of SAD as a misalignment of the sleep-wake phase with the body clock, circadian rhythms out of synch, and treat it with melatonin in the afternoon. Correctly timed melatonin administration shifts the rhythms of several hormones en bloc.[24] Another explanation is that vitamin D levels are too low when people do not get enough Ultraviolet-B on their skin. An alternative to using bright lights is to take vitamin D supplements.[40][41][42][43] However, one study did not show a link between vitamin D levels and depressive symptoms in elderly Chinese.[44] Incidence Nordic countries Winter depression is a common slump in the mood of some inhabitants of most of the Nordic countries. It was first described by the 6th century Goth scholar Jordanes in his Getica wherein he described the inhabitants of Scandza (Scandinavia).[45] Iceland, however, seems to be an exception. A study of more than 2000 people there found the prevalence of seasonal affective disorder and seasonal changes in anxiety and depression to be unexpectedly low in both sexes.[46] The study's authors suggested that propensity for SAD may differ due to some genetic factor within the Icelandic population. A study of Canadians of wholly Icelandic descent also showed low levels of SAD. [47] It has more recently been suggested that this may be attributed to the large amount of fish traditionally eaten by Icelandic people, in 2007 about 90kilograms per person per year as opposed to about 24kg in the US and Canada,[48] rather than to genetic predisposition; a similar anomaly is noted in Japan, where annual fish consumption in recent years averages about 60kg per capita.[49] Fish are high in vitamin D. Fish also contain docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), which has been shown to help with a variety of neurological dysfunctions. [50] To give an example of how widespread the popular understanding of SAD is, a character suffers from seasonal affective disorder in the Swedish Horror film Marianne. Other countries In the United States, a diagnosis of seasonal affective disorder was first proposed by Norman E. Rosenthal, MD in 1984. Rosenthal wondered why he became sluggish during the winter after moving from sunny South Africa to New York. He started experimenting increasing exposure to artificial light, and found this made a difference. In Alaska it has been established that there is a SAD rate of 8.9%, and an even greater rate of 24.9%[51] for subsyndromal SAD. Around 20% of Irish people are affected by SAD, according to a survey conducted in 2007. The survey also shows women are more likely to be affected by SAD than men. [52] An estimated 10% of the population in the Netherlands suffer from SAD.[53] SAD and bipolar disorder Most people with SAD experience major depressive disorder, but as many as 20% may have or may go on to develop a bipolar disorder (manic-depressive disorder). It is important to discriminate the improved mood associated with recovery from the winter depression and a manic episode because there are important treatment differences. [54] In these cases, people with SAD may experience depression during the winter and hypomania in the summer. Role of Occupational Therapy in Treating SAD Given that SAD impacts a wide variety of occupational performance areas in a person’s life as described in the aforementioned section, occupational therapists (OTs) play a key role in helping individuals cope with SAD. OTs incorporate best practices and principles from various health care disciplines into their therapeutic practice with clients with SAD, including assessment, treatment, and evaluation. Care and treatment are holistic and tailored to the client’s identified goals, needs, and responsiveness to treatments. In addition to educating clients on the etiology, prevalence, symptoms and occupational performance issues associated with SAD, OTs play a large role in treating patients or educating them on the different types of interventions available. Of particular importance is educating clients on fatigue management and energy conservation, as low energy level is commonly reported in people with SAD.[55] With increased energy levels, clients can hopefully return to doing activities that they need and want to do with respect to self-care, productivity, and leisure. The two main treatment approaches that OTs come across are the biomedical approach and the psychosocial approach. Biomedical approaches OTs can play a large role in educating their clients on biomedical interventions, which can be very effective in minimizing symptoms that impact occupational performance issues in the areas of leisure, productivity and self-care. OTs should be knowledgeable about the most commonly used biomedical treatment approaches, which are light therapy and pharmacotherapy, to address SAD. Light Therapy Bright light therapy, or phototherapy, has been used for over 20 years to treat SAD[56] with numerous studies citing its effectiveness.[57][58] Light therapy is recommended as a first-line treatment for SAD in Canadian, American, and international clinical guidelines.[58] The mood of individuals with SAD can improve with as little as 20 minutes of bright light exposure.[59] Bright light is more effective than dim light in protecting against “mood lowering” which commonly occurs in SAD.[59][60]p2 Light boxes are widely available devices which typically provide fluorescent light as a treatment for SAD.[56] OTs should be familiar with typical usage guidelines provided to users of light boxes and emphasize to clients the need for clinical monitoring to ensure the appropriate doses of light.[56] Effective doses of light therapy vary depending on the individual. Studies have shown effective doses ranging between 3,000 lux 2 hours/day for 5 weeks[61] to 10,000 lux 30 minutes/day for 8 weeks.[58] Patients are typically advised to sit “within several yards” of the device and glance occasionally (rather than stare) at it.[62]p20 Commercial light boxes are not regulated by U.S. law and, as such, OTs should recommend medical consultation and advise caution when selecting and using them.[56][62] Only 41% of SAD patients comply with clinical practice guidelines and use light therapy regularly due to reasons of inconvenience and ineffectiveness.[63] As such, OTs can help clients develop methods for incorporating light therapy effectively into their daily routines and complying with clinical guidelines.[64] [edit] Effectiveness Light therapy does not work for everyone. Twenty to fifty percent of those diagnosed with SAD do not gain adequate relief from it.[65] In addition to the lack of efficacy, the required time commitment and the tendency for recurrence are additional reasons why individuals with SAD explore alternative treatments to light therapy.[66] In a study comparing the effectiveness of light therapy and an antidepressant medication, fluoxetine, evidence was found to support the effectiveness and tolerability of both treatments for SAD.[58] Antidepressant Medications (Pharmacotherapy) Antidepressant medication (ADM) has been shown to be effective in treating various forms of depression.[67] Of the various types of ADMs used to treat SAD, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine and sertraline appear to be most effective.[68] OTs play a role in helping their clients understand how such medications, if prescribed, can decrease acute symptoms and lead to enhanced engagement in daily occupations. ADMs are considered to be largely compensatory in nature.[67] In other words, ADMs may suppress depressive symptoms while they are being used, but lasting changes are not guaranteed once treatment is discontinued. A growing body of evidence is showing that psychosocial approaches to therapy, such as cognitive and behavioural interventions, may have more enduring effects than biomedical interventions.[67] Psychosocial approaches to SAD interventions OTs play an important role in the implementation and recommendation of psychotherapeutic interventions, which follow psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery-based approaches. The roles of OTs in psychosocial rehabilitation often include the following: Identifying the clients' psychosocial issues, strengths and limitations associated with the condition Assessing clients’ readiness, motivation, and belief in their abilities to make changes in their lives Identifying what is meaningful to the client Identifying social support systems that are available to help the client achieve their goals.[69] OTs often use guiding frameworks, such as the Canadian Model of Occupational Performance[70] and the Model of Human Occupation[71] to help clients set rehabilitation goals and identify areas of occupational performance that are affected by the symptoms associated with SAD. Several types of interventions fall within the psychosocial scope of occupational therapy, and are used by an interdisciplinary team of health care providers who work with clients with SAD. In a health care system that is driven largely by medical models, OTs can play an important role in promoting psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery when addressing the underlying issues associated with SAD.[72] OTs use clinical reasoning to draw holistically upon principles of a variety of treatment approaches when implementing individual and group therapy among clients with SAD. Group Therapy OTs in mental health settings often lead groups for inpatients and outpatients with mood disorders.[73] Some group therapy topics that target occupational performance issues related to SAD could include: Stress management Weight control and nutrition Smoking cessation Substance abuse Time management Social skills and networking Wintertime activities Sleep education Self-esteem Sexual health These group therapy sessions are often guided by a number of different theoretical and therapeutic frames of references, which use methods that are shown by research to be effective. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy, Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy, Behavioural Activation, Problem-Solving Therapy, Positive Psychotherapy, Self-System Therapy and Outdoor Therapy are just some of the more common approaches that OTs use when framing their interventions for client with SAD. Cognitive Behavioural Therapy Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) is used widely by OTs to treat SAD and other mood disorders. Originally developed by Beck and colleagues,[74] CBT aims to help clients identify the expectations and interpretations that can lead them towards depression and anxiety; adjust to reality; and break through their avoidances and inhibitions. [75] When implemented appropriately, it can help people change their cognitive processes, which may then correspond with changes in their feelings and behaviours.[76] CBT for SAD focuses on the early identification of negative anticipatory thoughts and behavior changes associated with the winter season, and helps clients develop coping skills to address these changes.[77] By adopting a CBT approach, OTs can help clients with SAD engage in pleasurable activities in the winter months (i.e. behavioral activation) and help people think more positively (i.e. cognitive restructuring).[77] If qualified, OTs can deliver CBT skills training groups to SAD patients. The skills that OTs teach can have a direct impact on occupational performance issues and can include:[77] developing a repertoire of wintertime leisure interests using diaries to record automatic negative thoughts creating a balanced activity level improving time management skills problem solving about situations that initiate negative thinking setting goals and plans for maintaining gains and preventing relapse CBT, or a combination of CBT and LT, can lead to a significant decrease in levels of depression amongst those with SAD.[64][66] With non-seasonal depression, CBT appears to be about as effective as ADM in terms of acute distress reduction; however, the effects of CBT are shown to be longer lasting than ADM.[67][78] There have been no direct comparisons made between CBT and ADM specifically for SAD. [77] CBT is effective in treating both mild and more severely depressed patients, and is shown to prevent or delay the relapse of depressive symptoms better than other treatments for depression.[77][79] There are no known adverse physical side effects of CBT.[77] Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT) is an intervention that aims to increase meta-cognitive awareness to the negative thoughts and feelings associated with relapses of major depression.[80] Unlike CBT, MBCT does not emphasize changing thought contents or core beliefs related to depression. It instead focuses on meta-cognitive awareness techniques, which are said to change the relationship between one’s thoughts and feelings.[81] The act of passively and repetitively focusing one’s attention on the symptoms, meanings, causes, and consequences of the negative emotional state of depression is called rumination.[82] MBCT aims to reduce rumination by addressing the cognitive patterns associated with negative thinking and cultivating mindfulness through meditation and self-awareness exercises.[83] Once awareness of feelings and thoughts are cultivated, MBCT emphasizes accepting and letting them go.[83] OTs can train clients with SAD in MBCT skills, which often takes place in a group setting over a number of weeks. Training focuses on the concept of “decentering,” which is the [83] act of taking a present-focused and non-judgmental stance towards thoughts and feelings. By learning how to decenter, a person can distance themselves from the negative thoughts and feelings that may affect occupational performance in areas such as eating healthily, maintaining social relationships and being productive at work. By bringing attention back to the present (e.g. by focusing on their breath), clients gradually begin to observe their thought processes rather than reacting to them, thus, facilitating occupational engagement. Behavioural activation Behavioural activation (BA) is considered to be a traditional form of psychotherapy.[84] It is based on activity scheduling and aims to increase the number of positively reinforcing experiences in a person’s life. BA has shown comparable efficacy with other psychosocial therapies such as CBT, as well as with ADM treatment among mildly to moderately depressed patients.[85] BA has the potential to be very effective when used in occupational therapy, as it focuses on occupying one’s time with activities and experiences that are meaningful, positive, and engaging to the client. As such, clients who have occupational performance issues in productivity, leisure, and self-care may benefit from such therapy. Problem-solving therapies This intervention involves the patient creating a list of problems, identifying possible solutions, choosing the best solutions, creating a plan to implement them, and evaluating outcomes with respect to the problem. Further studies are needed to better understand the conditions under which problem-solving therapy is effective for depression;[86] however, this type of therapy is compatible with occupational therapy approaches to SAD. The Canadian Occupational Performance Measure (COPM)[87] is a widely used instrument that supports clients working with OTs in identifying their occupational needs, setting goals, and assessing change in occupational performance. Similar to the use of the COPM, OTs can use problem-solving therapy to focus on client choice and empowerment - principles that are fundamental to psychosocial rehabilitation and recovery.[88] Positive psychotherapy Positive psychotherapy (PPT) works to increase positive emotions in depressed clients and enhance engagement and meaning in activities that take place in a person’s life. Seligman and colleagues[89] found that group PPT was effective in treating mild to moderate depression for up to one year after the treatment was terminated. They also found that individual PPT led to greater remission rates than non-PPT treatments plus pharmacotherapy. OTs could adopt a PPT approach when conducting individual and group therapy sessions with clients with SAD. For example, they could introduce activities that instill success and learning, identify clients' interests, and encourage clients to engage in positive and personally meaningful occupations. Self-System Therapy Self-System Therapy (SST) is based on the notion that depression arises from chronic failure to attain personal goals due to one’s inability to self-motivate and pursue their goals.[90] SST is designed to improve one's ability to self-regulate and attain personal goals by helping define goals, identify the steps needed to attain them, identify the barriers that are preventing progress, and create a plan for how the goals may be achieved. This intervention draws upon techniques from cognitive therapy and BA, but has an overall emphasis on self-regulation. OTs can play a large role in helping SAD clients set and attain goals related to self-care, productivity, and leisure. Outdoor therapy Outdoor therapy is yet another psychotherapeutic intervention that OTs can recommend. Outdoor work has been used effectively as a therapy to treat those with mood difficulties during the winter season in Denmark.[91] As an example, horticulture groups have shown positive impacts on depressive symptoms, which can be associated with psychosocial adaptation leading to healthy occupational performance.[92] Similarly, outdoor walking can provide a “therapeutic effect” to individuals with SAD that is on par with light therapy.[93] OTs should incorporate outdoor occupations into their interventions with clients diagnosed with SAD. Assessments for SAD OTs also play a role in assessing and providing ongoing evaluation of clients who have SAD or who are suspected to have SAD. Assessments are most often used to determine if a particular treatment is working and what aspects of the disorder require the most attention. Two commonly used assessments for SAD are the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression – Seasonal Affective Disorder version (SIGH-SAD)[94] and the Beck Depression Inventory, 2nd edition (BDI-II).[95] The SIGH-SAD is a semi-structured interview that includes 21 non-seasonal depression items and an extra 8-item SAD-specific subscale. The BDI-II is quicker to administer and contains 21 measures of depressive symptom severity, which also captures atypical symptoms that are common in SAD. See also Circadian rhythm sleep disorder Depression (mood) Risks and benefits of sun exposure Social anxiety disorder Seasonal effects on suicide rates External links New York Times article on S.A.D. References 1. ^ Seasonal Depression can Accompany Summer Sun. Ivry, Sara. The New York Times. Retrieved September 6, 2008 2. ^ Lurie, Stephen J.; et al. (November 2006). "Seasonal Afective Disorder". American Family Physician 74 (9): 1521–4. PMID17111890. http://www.aafp.org/afp/20061101/1521.html. 3. ^ Friedman, Richard A. [1] “Brought on by Darkness, Disorder Needs Light”. New York Times’’, 2007-12-18. 4. ^ MedlinePlus Overview seasonalaffectivedisorder 5. ^ a b c Seasonal Affective Disorder by Mayo Clinic 6. ^ a b Rosenthal NE, Sack DA, Gillin JC, Lewy AJ, Goodwin FK, Davenport Y, Mueller PS, Newsome DA, Wehr TA. et al. (1984). "Seasonal Affective Disorder: A Description of the Syndrome and Preliminary Findings with Light Therapy". Archives of General Psychiatry 41 (1): 72–80. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790120076010. PMID6581756. 7. ^ a b c Marshall, Fiona. Cheevers, Peter (2003). "Positive options for Seasonal Affective Disorder", p.77. Hunter House, Alameda, Calif. ISBN 0-89793-413-X. 8. ^ a b Terman, M.; Terman, J.S. (2006). "Controlled Trial of Naturalistic Dawn Simulation and Negative Air Ionization for Seasonal Affective Disorder". American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (12): 2126–2133. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2126. PMID17151164. 17151164. 9. ^ "Properly Timed Light, Melatonin Lift Winter Depression by Syncing Rhythms" (Science Update). National Institute of Mental Health. 2006-05-01. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/science-news/2006/properly-timed-light-melatonin-lift-winter-de pression-by-syncing-rhythms.shtml. Retrieved 2009-08-30. 10. ^ Gabbard, Glen O. Treatment of Psychiatric Disorders. 2 (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing. p.1296. 11. ^ Rose, Phil Fox (2 November 2010). "SAD That DST is Ending--Dealing with the shortening days and the end of daylight-saving time". Busted Halo. http://www.bustedhalo.com/features/what-works-38-sad-that-dst-is-ending. Retrieved 3 November 2010. 12. ^ a b c d e f Lam, RW; Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, Enns MW, Morehouse R, Michalak EE, Tam EM (2006). "The Can-SAD Study: a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of light therapy and fluoxetine in patients with winter seasonal affective disorder". American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (5): 805–812. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.805. PMID16648320. 13. ^ a b c d e Avery, D H; Eder DN, Bolte MA, Hellekson CJ, Dunner DL, Vitiello MV, Prinz PN (2001). "Dawn simulation and bright light in the treatment of SAD: a controlled study". Biological Psychiatry 50 (3): 205–216. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01200-8. PMID11513820. 14. ^ a b c Modell, Jack; Rosenthal NE, Harriett AE, Krishen A, Asgharian A, Foster VJ, Metz A, Rockett CB, Wightman DS (2005). "Seasonal affective disorder and its prevention by anticipatory treatment with bupropion XL Biological Psychiatry". Biological Psychiatry 58 (8): 658–667. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.07.021. PMID16271314. 15. ^ Johansson, C; Smedh C, Partonen T, Pekkarinen P, Paunio T, Ekholm J, Peltonen L,Lichtermann D, Palmgren J, Adolfsson R, Schalling M (2001). "Seasonal affective disorder and serotonin-related polymorphisms". Neurobiology of Disease 8 (2): 351–357. doi:10.1006/nbdi.2000.0373. PMID11300730. 16. ^ Johansson, C; Willeit M, Levitan R, Partonen T, Smedh C, Del Favero J, Bel Kacem S, Praschak-Rieder N,Neumeister A, Masellis M, Basile V, Zill P, Bondy B, Paunio T, Kasper S, Van Broeckhoven C, Nilsson LG,Lam R, Schalling M, Adolfsson R. (2003). "The serotonin transporter promoter repeat length polymorphism, seasonal affective disorder and seasonality". Psychological Medicine 33 (5): 785–792. doi:10.1017/S0033291703007372. PMID12877393. 17. ^ Uz, T; Manev, H (2001). "Prolonged swim-test immobility of serotonin N-acetyltransferase (AANAT)-mutant mice". Journal of Pineal Research 30 (3): 166–170. doi:10.1034/j.1600-079X.2001.300305.x. PMID11316327. 18. ^ a b Avery, D. H.; Kizer D, Bolte MA, Hellekson C (2001). "Bright light therapy of subsyndromal seasonal affective disorder in the workplace: morning vs. afternoon Acta exposure". Psychiatrica Scandinavica 103 (4): 267–274. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00078.x. PMID11328240. 19. ^ Leppämäki, Sami; Haukka J, Lonnqvist J, Partonen T (2004). "Drop-out and mood improvement: a randomised controlled trial with light exposure and physical exercise ISRCTN36478292". BMC Psychiatry 4: 22. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-4-22. PMC514552. PMID15306031. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pmcentrez&artid=514552. 20. ^ Naish, John (2008-11-08). "Breakthroughs tips and trends: November 7th - Times Online". London: www.timesonline.co.uk. http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/life_and_style/health/article5106718.ece. Retrieved 2008-11-10. 21. ^ Rosenthal, Norman E.. (2006) Winter Blues, Revised edition, The Guilford Press, New York. ISBN 1-57230-395-6 22. ^ More, Lee Kremis. Gannett News Service. “It's Wintertime: When Winter Falls, Many Find Themselves In Need Of Light”, Milwaukee Sentinel, 1994-12-26. 23. ^ a b Nesse, Randolphe M; Williams, George C (1996). Why We Get Sick (First ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp.290. 24. ^ a b Bhattacharjee, Y (2007). "Psychiatric research. Is internal timing key to mental health?". Science 317 (5844): 1488–90. doi:10.1126/science.317.5844.1488. PMID17872420. http://www.ohsu.edu/ohsuedu/academic/som/images/Al-Lewy-Science.pdf. 25. ^ Howland, RH (2009). "Somatic therapies for seasonal affective disorder". J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 47 (1): 17–20. doi:10.3928/02793695-20090101-07. PMID19227105. 26. ^ |title=The Visible Light Spectrum |author=Zimmerman, Andrew |url=http://physics.about.com/od/lightoptics/a/vislightspec.htm |date=2012-02-15 27. ^ a b Saeeduddin Ahmed, Neil L Cutter, Alfred J. Lewy, Vance K. Bauer, Robert L Sack and Mary S. Cardoza (1995). "Phase Response Curve of Low-Intensity Green Light in Winter Depressives". Sleep Research 24: 508. ""The magnitude of the phase shifts [using low-level green light therapy] are comparable to those obtained using high-intensity white light in winter-depressives."" 28. ^ Strong, RE; Marchant, BK; Reimherr, FW; Williams, E; Soni, P; Mestas, R (2009). "Narrow-band blue-light treatment of seasonal affective disorder in adults and the influence of additional nonseasonal symptoms". Depression and Anxiety 26 (3): 273–8. doi:10.1002/da.20538. PMID19016463. 29. ^ J. J. Gooley, S. M. W. Rajaratnam, G. C. Brainard, R. E. Kronauer, C. A. Czeisler, S. W. Lockley (May 2010). "Spectral Responses of the Human Circadian System Depend on the Irradiance and Duration of Exposure to Light". Science Translational Medicine 2 (31): 31–33. doi:10.1126/scitranslmed.3000741. PMID20463367. http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/2/31.cover-expansion. 30. ^ "Valkee Bright Light Headset Research". http://www.valkee.com/uk/science.html#navigation. 31. ^ Beck, Melinda. (December 1, 2009) "Bright Ideas for Treating the Winter Blues". (Section title: "Exercise outdoors") The Wall Street Journal. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748703300504574567881192085174.html?m od=rss_Today%27s_Most_Popular 32. ^ "Applications: Health". Practical Solar. http://www.practicalsolar.com/applications.html. Retrieved 2009-06-09. 33. ^ "Grab the Sun With Heliostats". New York House. 2009-06-01. http://www.newyorkhousemagazine.com/pages/full_story?page_label=home_main_top&id =2631630&widget=push&instance=home_green_future&article-Grab%20the%20Sun%20 With%20Heliostats%20=&open=&. Retrieved 2009-12-08. 34. ^ Moscovitch, A; Blashko CA, Eagles JM, Darcourt G, Thompson C, Kasper S, Lane RM (2004). "A placebo-controlled study of sertraline in the treatment of outpatients with seasonal affective disorder". Psychopharmacology 171 (4): 390–7. doi:10.1007/s00213-003-1594-8. PMID14504682. 35. ^ Lam, Raymond W.; Anthony J. Levitt, Robert D. Levitan, et al. (May 2006). "The Can-SAD Study: A Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effectiveness of Light Therapy and Fluoxetine in Patients With Winter Seasonal Affective Disorder" (PDF). Am J Psychiatry 163 (5): 805–812. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.5.805. PMID16648320. http://day-lights.com/light-therapy-news/downloads/can-sad-study-wp.pdf. 36. ^ Terman, M.; Terman, J. S. (2006). "Controlled Trial of Naturalistic Dawn Simulation and Negative Air Ionization for Seasonal Affective Disorder". American Journal of Psychiatry 163 (12): 2126–33. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.12.2126. PMID17151164. 37. ^ Terman, M.; Terman, JS; Ross, DC (1998). "A Controlled Trial of Timed Bright Light and Negative Air Ionization for Treatment of Winter Depression". Archives of General Psychiatry 55 (10): 875–82. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.875. PMID9783557. 38. ^ Terman, M; Terman, JS (1995). "Treatment of seasonal affective disorder with a high-output negative ionizer". Journal of alternative and complementary medicine 1 (1): 87–92. doi:10.1089/acm.1995.1.87. PMID9395604. 39. ^ Lundt, L (2004). "Modafinil treatment in patients with seasonal affective disorder/winter depression: an open-label pilot study". Journal of Affective Disorders 81 (2): 173–8. doi:10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00162-9. PMID15306145. 40. ^ http://newfoundlandnews.blogspot.com/2008/01/sadness-seasonal-affective-disorder.html 41. ^ http://www.nowfoods.com/M092051.htm "Vitamin D Deficiency Linked to Low Mood State and Lowered Intellectual Ability in Elderly" 2006 42. ^ Lansdowne, AT; Provost, SC (1998). "Vitamin D3 enhances mood in healthy subjects during winter". Psychopharmacology 135 (4): 319–23. doi:10.1007/s002130050517. PMID9539254. 43. ^ Gloth Fm, 3rd; Alam, W; Hollis, B (1999). "Vitamin D vs broad spectrum phototherapy in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder". The journal of nutrition, health & aging 3 (1): 5–7. PMID10888476. 44. ^ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/03/090317142847.htm "Vitamin D May Not Be The Answer To Feeling SAD" Mar 2009 45. ^ Jordanes, Getica, ed. Mommsen, Mon. Germanae historica, V, Berlin, 1882. 46. ^ Magnusson, Andres; Axelsson, Johann; Karlsson, Mikael M.; Oskarsson, Högni (February 2000). "Lack of Seasonal Mood Change in the Icelandic Population: Results of a Cross-Sectional Study". Am J Psychiatry 157 doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.234. (2): 234–8. PMID10671392. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/157/2/234. 47. ^ Magnússon A, Axelsson J (1993). "The prevalence of seasonal affective disorder is low among descendants of Icelandic emigrants in Canada". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 50 (12): 947–51. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820240031004. PMID8250680. 48. ^ Fishery and Aquaculture Statistics: SECTION 2 - Food balance sheets and fish contribution to protein supply, by country from 1961 to 2007 Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2008 49. ^ Cott, Jerry; Joseph R. Hibbeln (February 2001). "Lack of Seasonal Mood Change in Icelanders" (Letter to the Editor). Am J Psychiatry (American Psychiatric Association) 158 (2): 328. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.328. PMID11156835. http://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/cgi/content/full/158/2/328. Retrieved 2008-09-02. "Thus, high levels of fish consumption should be considered a potential etiology for the finding of a lack of seasonal affective disorder among the Icelandic population." 50. ^ Horrocks, LA; Yeo, YK (1999). "Health benefits of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)". Pharmacological research: the official journal of the Italian Pharmacological Society 40 (3): 211–25. doi:10.1006/phrs.1999.0495. PMID10479465. 51. ^ Seasonal Affective Disorder and Latitude 52. ^ BreakingNews.ie - One in five suffers from SAD 53. ^ Elsevier – Dark Days: Winter Depression (Dutch) 54. ^ "Depression" (PDF). Mood Disorders Society of Canada. http://www.mooddisorderscanada.ca/documents/Consumer%20and%20Family%20Support /Depression.pdf. Retrieved 2009-08-08. 55. ^ Rosenthal NE. Winter blues: everything you need to know to bead seasonal affective disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 2006. 56. ^ a b c d New treatment options for seasonal affective disorder. Harvard Mental Health Letter 2008 11;25(5):6-7. 57. ^ Paino M, Fonseca-Pedrero E, Bousoño M, Lemos-Giráldez S. Light-therapy applications for DSM-IV-TR disease entities. The European Journal of Psychiatry 2009 07;23(3):166-176. 58. ^ a b c d Lam RW, Levitt AJ, Levitan RD, Enns MW, Morehouse R, Tam EM. The Can-STUDY: a randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of light therapy and fluoxetine in patients with winter seasonal disorder. Am J Psychiat 2006; 163:805-812. 59. ^ a b Virk G, Reeves G, Rosenthal NE, Sher L, Postolache TT. Short exposure to light treatment improves depression scores in patients with seasonal affective disorder: A brief report. International Journal on Disability and Human Development 2009 07;8(3):283-286. 60. ^ aan het Rot M, Benkelfat C, Boivin DB, Young SN. Bright light exposure during acute tryptophan depletion prevents a lowering of mood in mildly seasonal women. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology 2008; 18: 14-23. 61. ^ Ruhrmann S, Kaspar S, Hawellek B, Martinez B, Hoflich G, Nickelsen T, Moller HJ. Effects of fluxetine versus bright light in the treatment of seasonal affective disorder. Psychol Med 1998; 28: 923-833. 62. ^ a b Howland RH. Somatic therapies for seasonal affective disorder. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv 2009;47(1):17-20. 63. ^ Schwartz PJ, Brown C., Wehr TA, Rosenthal NE. Winter seasonal affective disorder: a follow-up study of the first 59 patients of the National Institute of Mental Health Seasonal Studies Program. Am J Psychiat 1996; 153: 1028-1036. 64. ^ a b Rohan KJ, Roecklein KA, Lacy TJ, Vacek PM. Winter depression recurrence one year after cognitive-behavioral therapy, light therapy, or combination treatment. Behav Ther 2009; 40: 225–238. 65. ^ Cognitive behavioral therapy may be an option for treating seasonal affective disorder. Harvard Mental Health Letter 2010 02;26(8):7-7. 66. ^ a b Rohan KJ, Roecklein KA, Tierney Lindsey K, Johnson LJ, Lippy RD, Lacy TJ, Barton FB. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioral therapy, light therapy, and their combination for seasonal affective disorder. J Consult Clin Psych 2007; 75: 489-500. 67. ^ a b c d Hollon S. D., Stewart M. O., Strunk D. (2006). "Enduring effects for cognitive behavior therapy in the treatment of depression and anxiety". Annual Review of Psychology 57: 285–315. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190044. PMID16318597. 68. ^ Moscovitch A, Blashko CA, Eagles JM, Darcourt G, Thompson C, Kasper S, Lane RM. A placebo-controlled study of sertraline in the treatment of outpatients with seasonal affective disorder. Psychopharmacology 2004; 171:390–397. 69. ^ Ikiugu M. The new occupational therapy paradigm: implications for integration of the psychosocial core of occupational therapy in all clinical specialties. Occup Ther Ment Health 2010; 26:343–353. 70. ^ Law M, Polatajko H, Baptiste S, Townsend E. Core concepts of occupational therapy. In: Townsend E, editor. Enabling occupation: an occupational therapy perspective. Ottawa. Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists; 2002. 71. ^ Kielhofner G. A model of human occupation — theory and application. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1995. 72. ^ Krupa T, Clark C. Occupational therapy in the field of mental health: promoting occupational perspectives on health and well-being. Can J Occup Ther 2004 Apr; 71(2): 69-74. 73. ^ Sundsteigen B, Eklund K, Dahlin-Ivanoff S. Patients’ experience of groups in outpatient mental health services and its significance for daily occupations. Scand J Occup Ther 2009; 16: 172-180. 74. ^ Beck AT, Rush JA, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive therapy of depression. New York: Guilford Press; 1979. 75. ^ Weinrach SG. Cognitive therapists: a dialogue with Aaron Beck. J Couns Dev 1988; 67:159-164. 76. ^ Ikiugu MN. Psychosocial conceptual practice models in occupational therapy: building adaptive capability. St. Louis: Mosby Elsevier; 2007. 77. ^ a b c d e f Rohan KJ. Coping with the seasons: A cognitive-behavioral approach to season affective disorder therapist guide. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. 78. ^ Driessen E, Hollon SD. Cognitive behavioral therapy for mood disorders: efficacy, moderators and mediators. Psychiatric Clinics N Am 2010; 33: 537-555. 79. ^ DeRubeis RJ, Hollon ST, Amsterdam JD, Shelton RC, Young PR, Salomon RM, O’Reardon JP, Lovett ML, Gladis MM, Brown LL, Gallop R. Cognitive therapy vs medications in the treatment of moderate to severe depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005; 62: 409-416. 80. ^ Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: a new approach to preventing relapse. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. 81. ^ Scherer-Dickson N. Current developments of metacognitive concepts and their clinical implications: Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression. Couns Psych Quar 2004; 17(2): 223–234. 82. ^ Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. J Abnorm Psych 2000; 109: 504–511. 83. ^ a b c Hick SF, Chan L. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: effectiveness and limitations. Soc Work Ment Health 2010; 8: 225-237. 84. ^ Lau MA. New developments in psychosocial interventions for adults with unipolar depression. Curr Opin Psychiat 2008, 21:30–36. 85. ^ Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Behavioral activation treatments of depression: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev 2006; 27:318–326. 86. ^ Cuijpers P, van Straten A, Warmerdam L. Problem solving therapies for depression: a meta-analysis. Eur Psychiatry 2007; 22:9–15. 87. ^ Law M, Baptiste S, McColl MA, Opzoomer A, Polatajko H, Pollock N. The Canadian occupational performance measure: An outcome measure for occupational therapy. Can J Occup Ther 1990; 57: 82–87. 88. ^ Kirsh B, Cockburn L. The Canadian occupational performance measure: a tool for recovery-based practice. Psychiatric Rehab J 2009; 32(3): 171–176. 89. ^ Seligman EP, Rashid T, Parks AC. Positive psychotherapy. Am Psychol 2006; 61:774–788. 90. ^ Strauman TJ, Vieth AZ, Merrill KA et al. (2006). "Self-system therapy as an intervention for self-regulatory dysfunction in depression: a randomized comparison with cognitive therapy". J Consult Clin doi:10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.367. PMID16649881. Psychol 74 (2): 367–376. 91. ^ Hahn IH, Grynderup MB, Dalsgaard SB, Thomsen JF, Hansen AM, Kaergaard A, et al. Does outdoor work during the winter season protect against depression and mood difficulties? Scand J Work Environ Health 2011 Mar 1. 92. ^ Fieldhouse J. The impact of an allotment group on mental health clients’ health, wellbeing and social networking. Br J Occup Ther 2003; 66(7): 286-296. 93. ^ Wirz-Justice A, van der Velde P, Bucher A, Nil R. Comparison of light treatment with citalopram in winter depression: a longitudinal single case study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 1992; 7: 109–116. 94. ^ Williams JB, Link MJ, Rosenthal NE, Amira L, Terman M. Structured interview guide for the Hamilton depression rating scale – seasonal affective disorder version (SIGH-SAD). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1992. 95. ^ Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck depression inventory – 2nd edition manual. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. External links Seasonal Affective Disorder at the Open Directory Project Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Seasonal_affective_disorder&oldid=509 141649"