* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Roman Gladiators - Lake Oswego High School

Military of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

The Last Legion wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Switzerland in the Roman era wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Demography of the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman emperor wikipedia , lookup

Roman economy wikipedia , lookup

History of the Roman Constitution wikipedia , lookup

Romanization of Hispania wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Roman funerary practices wikipedia , lookup

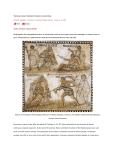

Roman Gladiators Gladiators (from Latin gladiatores) were both professional and amateur fighters in ancient Rome who fought for the entertainment of its “civilized” spectators. These matches took place in arenas in throughout the empire and for the bulk of its history. Man vs. man and man against animal engagements, in combat that was at times to the death, was the ancient world sport that rivaled all of modern society spectacles rolled into one. It’s possible that the origin of the “games” was rooted in the Estruscan custom of ritual human sacrifices to honor the dead. The first gladiatorial contest in Rome took place in 264 BC as part of one of these funeral rituals called a munus. Marcus and Decimus Junius Brutus staged a gladiatorial combat in honor of their deceased father with three pairs of slaves serving as gladiators in the Forum Boarium (a commercial area that was named after the Roman cattle market). The concept of the munus was that it kept alive the memory of an important individual after death. They were held some time after the funeral and were often repeated at annual or fiveyear intervals. Gladiatorial games, or munera were not made a regular part of public games until the late first century. A contemporary second century AD scholar, Festus, (who abridged the work of the Augustan era writer Verrius Flaccus) suggests that gladiatorial combat was a substitution for an original sacrifice of prisoners on the tombs of great warriors. Tertullian, a Christian writer also of the second century, claimed that gladiatorial combat was a human sacrifice to the manes or spirits of the dead. Gladiator matches took place in amphitheatres (like the Flavian Amphitheatre or Colosseum) and were staged after the venationes (animal fights) and public executions (noxii). In its earliest forms, individuals of patrician or equestrian status organized these, often to gain political favor with the public. The organizer of any of these games was called the editor, munerator, or dominus and he was honored with the official signs of a magistrate. In the Imperial period, the Emperors were nearly solely responsible, excepting cases with special permission, for these all inclusive public ludi circenses, or "games". Gladiators were typically recruited from criminals, slaves, and prisoners of war. If selected for such duty, having lost, or never had, the rights of a citizen, there was no choice but to comply for these “recruits”. Provided that one had desirable physical appearance and abilities, the arena could be a likely destination. Some free-born men as well, although they had not lost their citizen rights, voluntarily chose the profession and pledged themselves to the owner (lanists) of a gladiatorial troupe (familia) by (according to Petronius) swearing an oath "to endure branding, chains, flogging or death by the sword". It has been estimated that by the end of the Republic, about half of the gladiators were volunteers (auctorati), who took on the status of a slave for an agreed-upon period of time, similar to indentured servitude that was common in the late second millennium. These auctorati, by taking the gladiator’s oath, agreed to be treated as a slave and suffered the ultimate social disgrace (infamia). Seneca described this oath as "most shameful". The potential advantages for this new career could outweigh the alternatives, however. Aside from the potential for public fame and fortune, including liaisons with Roman women of even aristocratic status, the gladiator recruit became a member of a cohesive group that was known for its courage, good morale, and absolute fidelity to its master to the point of death. Life became a model of military discipline and through courageous behavior he was also now capable of achieving honor similar to that enjoyed by Roman soldiers on the battlefield. Gladiators were trained in special schools called ludi, which could be found as commonly as amphitheatres throughout the empire. There were four schools in Rome itself, the largest of which was called the Ludus Magnus, which was connected to the Colosseum by an underground tunnel. Among the most famous is the school at Capua where the slave rebellion of Spartacus was sparked in 73 BC. Typically, like modern boxers, most gladiators would not fight more than 2 or 3 times a year and with enough fame and fortune they could purchase their freedom. Some, however, such as criminals, were either expected to die within a year (ad gladium), or might earn their release after three years (ad ludum), if they survived. Unlike the movie “Gladiator” with Russell Crowe, gladiators usually fought in single pairs (Ordinarii), in one on one combat. Sponsors of the games or special audiences could, however, request other combinations like several gladiators fighting together (Catervarii), or specific gladiators against each other even from outside the established troupe (Postulaticii). Occasionally, lanista used substitutes (supposititii) if a scheduled or requested gladiator was killed or wounded. In the imperial era, Emperors could have their own team called Fiscales. Mr. Noble 1 Roman Gladiators Again, contrary to what is seen in most movies, gladiatoral combat was less likely to result in death than is depicted. Gladiators were expensive to maintain, train and replace in the event of death, and keeping the most popular of crowd pleasers alive was far more practical than the alternative. That’s not to say, however, that death wasn’t common among the non-elite. In these cases, when a gladiator had overpowered his opponent, he would turn to the spectators for a reaction from the crowd. The defeated gladiator would possibly raise his left hand asking for his life to be spared. If the spectators turned their thumbs up yelling 'missum', they wished to spare his life, but if they turned their thumbs down yelling 'iugula', they wished the victor to finish him. The final decision in this was usually left to a single judge. In the presence of the Emperor, the judgment belonged to him, but otherwise it may rest with the games munerator or sponsor. There are many such events depicted on frescoes or mosaics. In one specific example, the result of a fight is shown in an inscription (Astyanax defeated Kalendio) with the symbol of death (a circle with a diagonal line through it) marked over the loser. Another possibility related to the thumbs up/down debate is that the crowd raised their fists but kept their thumb inside it if they wanted the loser to live, and pointed down to indicate death. If the audience felt both men fought admirably, or witnessed a bout between two popular gladiators, they would likely want both to live and fight another day. A gladiator who won several fights, or served an indefinite period of time was allowed to retire, in many cases to continue as a gladiator trainer. Those who did win or buy their freedom, or at times at the request of the crowd or Emperor, were given a wooden sword (rudis) as a memento. Gladiatoral contests were first known to be outlawed by Constantine I in 325 AD, but they did continue through the mid 5th century. The Emperor Honorius is credited with putting a stop to it as the western empire was nearing its fall. The last known gladiator competition in the city of Rome occurred on January 1, 404. Some interesting gladiator facts: The Emperor Commodus liked to stage fights between dwarfs and women. He also appeared no less than 735 times on the stage in the character of Hercules, with club and lion’s skin, and in a position of little risk of harm to himself, he killed countless beasts and men. Tacitus in his Annals writes about Roman emperor Nero staging "a number of gladiatorial shows, equal in magnificence to their predecessors, though more women of rank and senators disgraced themselves in the arena". in 63 AD Petronius' Satyricon mentions a Roman circus, which featured a female chariot fighter competing against men. According to Suetonius, the Emperor Domitian (reigned AD 81-96) made women gladiators fight by torchlight at night. Women were members of the venatores, according to the writings of Martial and Cassius Dio. Emperor Septimius Severus issued an edict prohibiting women combatants in the arena in 200 AD. Caesar's large-scale exhibitions prompted the Roman Senate to limit the number of contestants. For his daughter Julia’s funeral games, he pitted 300 pairs of gladiators. The largest contest of gladiators was given by the emperor Trajan as part of a victory celebration in 107 AD in Dacia and included 5000 pairs of fighters. Mr. Noble 2 Roman Gladiators Roman Gladiator Types Different gladiators specialized in different weapons and tactics. The following illustrates these various styles and equipment. Of these, Thracians, Mirmillones, Retiarii, and Secutores were four of the most common. Andabatae: (1st cent. BC) Clad in chainmail like eastern cavalry (cataphracti), wore visored helmets without eyeholes. They charged blindly at one another on horseback as an ancient precursor to the medieval joust. Bestiarii: (beast fighters) originally armed with a spear or knife, these gladiators were condemned to fight beasts with a high probability of death. In later times, the Bestiarii were highly trained, specializing in various types of exotic, imported beasts. Dimachaeri: Used two-swords, one in each hand. Equites: Fought on horseback with a spear and gladius, dressed in a full tunic, with a manica (arm-guard). Generally, the Eques only fought gladiators of his own type. Essedari: Celtic style charioteers, likely first brought to Rome from Britain by Caesar. Hoplomachi (heavily armed) or Samnite: Fully armored, and based on Greek hoplites. They wore a helmet with a stylized griffin on the crest, woolen quilted leg wrappings, and shin-guards. They carried a spear in the Hoplite style with a small round shield. They were paired against Mirmillones or Thraces. Laquerii: Laqueatores used a rope and noose. Mirmillones (or murmillones): Wore a helmet with a stylized fish on the crest (the mormylos or sea fish), as well as an arm guard (manica). They carried a gladius and an oblong shield in the Gallic style. They were paired with Hoplomachi or Thraces. Provocatores (challengers): Paired against the Samnites but their armament is unknown and may have been variable depending on the games. Retiarii: Carried a trident, a dagger, and a net, a larger manica extending to the shoulder and left side of the chest. They commonly fought secutores or mirmillones. Occasionally a metal shoulder shield, or galerus, was added to protect the neck and lower face. Saggitarii: Mounted bowman armed with reflex bows capable of propelling an arrow a great distance. Samnites: see Hoplomachi. Secutores: Had the same armour as a murmillo, including oblong shield and a gladius. They were the usual opponents of retiarii. Scissores (carvers): Little is known about this ominous sounding gladiator. Thraces: The Thracian was equipped with a broad-rimmed helmet that enclosed the entire head, a small round or square-shaped shield, and two thigh-length greaves. His weapon was the Thracian curved sword, or the sica. They commonly fought mirmillones or hoplomachi. Velites: Fought on foot, each holding a spear with attached thong in strap for throwing. Named for the early Republican army units of the same name. Venatores: Specialized in wild animal hunts. Technically not gladiators, but still a part of the games. One more type deserving mention is the Praegenarii who were used as an ancient opening act to get the crowd in the mood. They used a rudis (wooden sword) and wore wrappings around body. As they fought, they were accompanied by music (cymbals, trumpets, and hydraulis water organ). Mr. Noble 3