* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Jasmine Wong

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

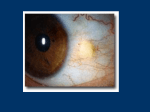

There's a black sheep in every flock Jasmine Wong Yumori Optometry Resident West LA VA Health Center ABSTRACT 35 year old White male with the initial complaint of redness in both eyes, more in his right than left eye, presents with a vascularized conjunctival lesion. Excisional biopsy results reveal a rare conjunctival plasmacytoma. Key words: Plasmacytoma, SEMP, multiple myeloma, conjunctival tumor, excisional biopsy CASE REPORT A 33 year old white male presented to our clinic with a complaint of constant redness in both eyes, more in his right than left eye. The patient’s ocular and medical histories were negative and he denied any medications or allergies. His family ocular history was positive for glaucoma in his paternal grandfather. He was oriented to time, place, and person. His pupils were equally round and reactive to light without any afferent papillary defect, extraocular motilities were unrestricted in all gazes, and confrontation visual fields were full to finger counting in both eyes. His uncorrected visual acuity was 20/20- in each eye; with manifest refraction of +0.50DS in both eyes his best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. Intraocular pressures were 20 mmHg in each eye pre-dilation at 9:45AM and 23 mmHg in each eye at 11:00AM post-dilation with Goldmann applanation tonometry. Anterior segment evaluation with slit lamp examination revealed clogged meibomian glands and inflamed nasal pterygia 1.8 mm across the limbus in his right eye and 2.4 mm in his left eye. A mildly elevated, mobile, faint pink, vascularized, 4.5mm by 4.5 mm lobular temporal bulbar conjunctival lesion in his right eye was also noted. His dilated fundus examination was unremarkable in both eyes with a cup to disc ratio of 0.40 with healthy rims in both eyes. The patient diagnosed with inflamed pterygia and meibomitis in both eyes and a suspicious bulbar conjunctival lesion in his right eye. He was started on Acular four times a day in both eyes for seven days, lid hygiene was initiated, and he was asked to return to clinic for 3 months for monitoring, respectively. Based on his post-dilated IOP spike, he was also considered a glaucoma suspect and an IOP check and baseline threshold visual field examination was requested at his follow-up visit. The patient failed to return at the requested follow-up time and instead returned to clinic a year and a half later complaining of continuing redness in both eyes for the past two and a half years and requested an eye drop to occasionally use to decrease redness. He reported that the Acular previously prescribed did not help and Visine helped only temporarily; he also commented that the vascular lesion in his right eye had been stable for the past one to two years. Ocular findings revealed a follicular reaction in the inferior palpebral conjunctiva of both eyes and stable nasal pterygia in both eyes and suspicious bulbar conjunctival lesion in his right eye. Intraocular pressures were 16 mmHg in both eyes at 2:09PM with Goldmann applanation tonometry and he deferred dilation. Patanol and artificial tears were started two and four times a day, respectively, in both eyes for follicular conjunctivitis, warm compresses and lid hygiene was re-advised for meibomitis, and a consult to ophthalmology and for an anterior segment photo were placed for further evaluation of his conjunctival lesion in his right eye in two weeks. An IOP check, baseline visual field, baseline stereo disc photos, and dilation were also deferred to his follow-up examination. Two weeks later anterior segment findings were similar to prior examinations and intraocular pressures were 20 mmHg in both eyes at 10:00AM with Goldmann applanation tonometry. The dilated fundus examination was unremarkable and a trial of PredForte every two hours in the right eye with a slow taper was initiated to rule out an inflammatory process in the conjunctival lesion. Follow-up was scheduled in three weeks for consideration of excisional biopsy but the patient was lost to follow-up. Three years later the patient returned for evaluation of the conjunctival lesion. He reported growth of the conjunctival lesion since his prior examinations with increased redness and foreign body sensation in both eyes. He declined any medications, including any eye drops, and his incoming visual acuities remained 20/20 in each eye. During anterior segment evaluation with a slit lamp examination revealed a papillary reaction in both eyes, nasal pterygia now 2.0 mm across the limbus in his right eye and 2.7 mm in his left eye. The elevated conjunctival lesion was now noted to be 4.6mm by 5.8 mm with two larger feeder vessels in his temporal bulbar conjunctival lesion in his right eye was also noted. Dilation was again deferred by the patient, anterior segment photos were taken in both eyes, and excisional biopsy of the conjunctival lesion in the right eye was planned in two months. Subsequent excisional biopsy of pterygia was also considered. Excisional biopsy of the conjunctival lesion was performed and histology revealed a plamacytoma, monoclonal kappa. Immunochemistry with CD138 and K/L light chain stains supported the diagnosis. A consult to the oncology service for systemic evaluation was placed, order for an MRI to rule out orbital involvement, and a dilated fundus examination with B-scan was planned to rule out choroidal involvement. Post-operative examinations day one and week one were otherwise uneventful; conjunctival sutures were intact with no gaping and Ocuflox and PredForte four times a day in the right eye were completed for a week with a slow PredForte taper. The dilated fundus examination with Bscan revealed no posterior segment involvement, MRI was normal, and a thorough systemic evaluation for plasma cell dyscrasis with the oncology service revealed no systemic involvement. At his post-operative month one examination there was increase in redness at the excision site and concern for recurrence versus post-op inflammation. The patient was restarted on PredForte four times a day in the right eye with a slow taper, anterior segment photography was repeated, and follow-up has been scheduled for one month. The differential diagnoses may be extensive. Listed below are the differential diagnoses, and associated clinical and histopathologic signs, that were considered in this case. Definitive diagnoses may only be achieved through biopsy and histopathologic studies. Clinical and histopathologic descriptions, unless otherwise cited, are from Shields C.L., Shields J.A. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Survey of Ophthalmology 2004; 49(11): 3-24. Papilloma: Papillomas are pink fibrovascular fronds arranged in either a sessile or pedunculated configuration; histopathologically, papillomas show numerous vascularized papillary fronts lined by acanthotic epithelium. Amelanotic nevus: Composed of nests of benign melanocytes in the stroma near the base layers of the epithelium, nevi are typically located in the interpapebral bulbar conjunctiva near the limbus; precautions are employed during excision to prevent recurrence should the lesion prove to be a melanoma. Amelanotic melanoma: Melanomas are clinically variable but typically have prominent feeder vessels and histopathologically are composed of variably pigmented malignant melanocytes within the conjunctival stroma. Lymphoid tumor: Appearing as a diffuse, slightly elevated pink pass in the stroma or deep to Tenon’s fascia, lymphoid tumors appear similar to that of smoked salmon. Histopathologically, lymphoid tumors appear as sheets of lymphocytes and may be classified as reactive lymphoid hyperplasia or malignant lymphoma. Granuloma: A benign lesion, granulomas appear elevated red masses with a florid blood supply. Pyogenic granulomas are composed of granulation tissue with chronic inflammatory cells and numerous small caliber blood vessels. Plasma cell granulomas in particular are composed of mature plasma cells and lymphocytes, eosinophils, fibroblasts, and capillary endothelial hyperplasia (Seddon et al., 1982). Granuomas may respond to topical corticosteroids but many require excision. After excisional biopsy and histopathology confirm plasmacytoma, laboratory testing is needed to definitively diagnose a plasmacytoma secondary to manifestation of systemic multiple myeloma or a solitary extramedullary lesion. Multiple myeloma is a systemic disease associated with plasma cell infiltration of bone marrow and osteolytic lesions; monoclonal immunoglobin may also be present in serum and urine. In contrast, patients with SEMP have normal bone marrow, urine, serum electrophoresis, and hemoglobin. Histopathologically the tumor consists of sheets of mature plasma cells. Other diagnoses that may be considered include: Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia: Histopathologically, conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasias demonstrate either partial or nearly full thickness replacement of the surface epithelium by abnormal epithelial cells that lack normal maturation. They usually occur at the limbus in the interpapebral fissure and a white plaque may be visualized on the surface of the lesion due to secondary hyperkeratosis. Squamous cell carcinoma: An extension of abnormal epithelial cells through to the conjunctival stroma, squamous cell carcinoma are characterized histopathologically by malignant squamous cells that have violated the basement membrane and have grown in sheets or cords into the stromal tissue. They appear larger and more elevated than a conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. DISCUSSION Plasmacytomas are tumors of plasma cell origin (Adkins et al., 1996) that have become modified to produce large amounts of immunoglobulin (Shields, 1989). Plasmacytomas may be a primary or secondary tumor focus, the distinction of which is based on the presence of systemic disease. Primary plasmacytomas may be divided into medullary, referring to bone lesions, or extramedullary, referring to soft tissue lesions (Salmon & Cassady, 1997). Known as a solitary extramedullary plamacytoma (SEMP), primary lesions represent 3% of plasma cell neoplasms (Aboud, Sullivan, & Whitehead, 1995), are locally invasive, and do not metastasize often. According to Benlin and Inci (1995), SEMP arise from B-type lymphocytes that originate in the bone marrow, migrate to the peripheral lymphoid tissues, and then undergo plasmacytoid differentiation. While the majority of SEMP develop in the walls of the upper respiratory tract or nasopharynx, ocular involvement by SEMP is very rare. As SEMP may be composed of premalignant B cells with no bone involvement, criteria for diagnosis of SEMP include negative lymph node assessment, skeletal survey, bone marrow biopsy, and computed tomography (De Smet & Rootman, 1972). Urine examination for Bence Jones proteins, serum protein estimation, and serum protein electrophoresis may also be used to help exclude generalized disease (Vyas, Vyas, & Chaudhary, 1984). Histological diagnosis is made when sheets of monomorphic neoplastic plasma cells are seen without inflammatory cells or other features of inflammatory granulomas (Vyas, Vyas, & Chaudhary, 1984). SEMP may be a future indicator of multiple myeloma (Kremer, Flex, & Manor, 1990). Secondary lesions stem from plasma cell infiltration of the bone marrow and monoclonal immunoglobulin in the serum, leading to anemia, bone pain, pathologic fractures, renal insufficiency, infection, and plasmacytomas (Douglas & Gibson, 1996). Secondary plasmacytomas are manifestations of multiple myeloma, are more aggressive and metastatic, and represent approximately 1% of cancers and 10% of hematologic malignancies (Salmon & Cassady, 1997). Besides periocular plasmacytoma, other ophthalmic features of multiple myeloma include retinal vascular manifestations of hyperviscocity, corneal crystals, ciliary body cysts, and papilledema (Knapp, Gartner, & Henkind, 1987). Death is usually caused by infection and renal insufficiency (De Smet & Rootman, 1972). TREATMENT AND MANAGEMENT Therapeutic options for SEMP include external beam radiotherapy (De Smet & Rootman, 1972) and local excision (Kremer, Flex, & Manor, 1990), or radiotherapy after surgical excision. The mean survival time is 8.3 years (Tetsumoto, Iwaki, & Inoue, 1993). Treatment for secondary plasmacytomas includes local irradiation and systemic chemotherapy along with a bone marrow transplant; mean survival time is 20 months (Tetsumoto, Iwaki, & Inoue, 1993). CONCLUSION This case report represents a rare case of a solitary extramedullary plamacytoma in the conjunctiva. Although plasmacytomas of the eye and orbit are rare, eye care practitioners must be familiar with ophthalmic manifestations of these tumors that may or not be associated with multiple myeloma and plasmacytomas must be included in the spectrum of ocular masquerade syndrome. The ultimate diagnosis of plasmacytoma is made by biopsy and histopathologic examination of the tissue. Long-term follow up, including periodic systemic evaluation, is required to establish that orbital involvement is not an early manifestation of multiple myeloma. BIBLIOGRAPHY Aboud N., Sullivan T., Whitehead K. Primary extramedullary plasmacytoma of the orbit. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1995; 23: 235-9. Adkins J.W., Shields J.A., Shields C.L., Eagle Jr. R.C., Flanagan J.C., Campanella P.C. Plasmacytoma of the eye and orbit. International Ophthalmology. 1996; 20(6): 39-343. Benli K., Inci S. Solitary dural plasmacytoma: case report. Neurosurgery 1995 June; 36(6): 1206-9. De Smet M.D., Rootman J. Orbital manifestations ofplasmacytic lymphoproliferations. Ophthalmology 1987; 94: 995-1003. Douglas DE, Gibson J. Diagnosis and treatment of multiple myeloma. In: Wiernik PH, Canellos GP, Dutcher JP, Kyle RA (eds) Neoplastic diseases of the blood. 3rd ed. New York: Churchill Livingston, 1996: 561-83. Knapp A.J., Gartner S., Henkind P. Multiple myeloma and its ocular manifestations. Surv Opthalmol 1987; 31: 343-351. Kremer I, Flex D, Manor R. Solitary conjunctival extramedullary plasmacytoma. Ann Ophthalmol 1990; 22: 126-30. Salmon S.E., Cassady J.R. Plasma cell neoplasms. In: DeVita VT, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA, editors. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. 5th ed, vol. 2. Philadelphia: Lippencott-Raven Publishers, 1997: 2344-2396. Seddon, J.M., Corwin, J.M., Weiter, J.J., Brisbane, J.U., & Sutula, F.C. Solitary extramedullary plasmacytoma of the palpebral conjunctiva. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982 Jul; 66(7):450-4. Shields J.A. Lymphoplasmacytoid tumors. In: Shields JA. Diagnosis and Management of Orbital Tumors. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders, 1989: 3304. Shields C.L., Shields J.A. Tumors of the conjunctiva and cornea. Survey of Ophthalmology 2004; 49(11): 3-24. Tetsumoto K., Iwaki H, Inoue M. IgG-kappa extramedullary plasmacytoma of the conjunctiva and orbit. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1993; 77: 255-257. Vyas MC, Vyas SP, Chaudhary RK. Primary extramedullary solitary plasmacytoma of conjunctiva--a case report. Indian J Ophthalmol. 1984 MayJun;32(3):181-3.