* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Click here - Walkington News

Survey

Document related concepts

Allies of World War I wikipedia , lookup

Technology during World War I wikipedia , lookup

Australian contribution to the Allied Intervention in Russia 1918–1919 wikipedia , lookup

Allied intervention in the Russian Civil War wikipedia , lookup

World War I in popular culture wikipedia , lookup

List of World War I memorials and cemeteries in Artois wikipedia , lookup

The Birtley Belgians wikipedia , lookup

Economic history of World War I wikipedia , lookup

History of Germany during World War I wikipedia , lookup

History of the United Kingdom during the First World War wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

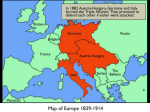

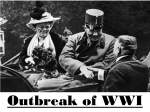

1914 - 1919 One hundred years on, a look back at the times and lives of the people of Walkington and the men who paid the ultimate price in the bloodiest conflict in history. Walkington in 1914 Walkington during the Great War was a small rural community of around 1,288 people, which included 591 inmates and 95 staff of the East Riding Asylum (later Broadgate Hospital). Life revolved around work or school, chapel, church or the ‘alternative pew ‘of the public house. At all Hallows Church the Reverend Michael Watson Bodley Dawe was the rector living at what we now know as the Old Rectory, he and his wife Mary came from the West Country, and were looked after by a cook called Eliza Brooks and a housemaid called Sarah Williamson. His total flock was 600 people, and the rest of the population attended the two chapels in the village. At that time these were the Primitive Methodist Chapel on East End and the Jubilee Methodist Chapel on West End. (The Primitive and Wesleyan chapels did not join together until 1962). Presiding at the school on Northgate was Mr Samuel Stafford Granger, assisted by Mr. J. R. Hayward, who would answer the call to arms in 1915, and Miss. Skingle, Miss. Mathews and Miss. Smith. Mr. Granger himself also went off to war in 1917. The Parish council led by the Reverend Dawe met at the Board School. The inhabitants were provided with local shops run by Miss. Rose Farrow and Mr. Edward Page, Miss. Farrow’s shop was on West End this is now number 24. The village blacksmith was Mr. Tom Bailey, and children returning home from school loved to stop at the forge at the Ferguson Fawsitt Arms to watch him shoeing horses and for a treat helping to blow the bellows. The joiner and wheelwright Mr. Rotsey Lawson was across the road, the local builder Sam Lythe was at Kirk View up Kirk Lane. Any goods required from Beverley or Hull where collected by one of the two carriers Fred Ridsdale or John Tom Anderson. There were six market gardeners, all growing produce to send to market. A butcher Mr. Fred Willie at the bottom of Northgate would slaughter and sell his own meat and this too was a source of entertainment for children leaving school. He was assisted in this by Jim Smith who later took over from him and was known by all as ‘Butcher Jim’. The post office was the domain of Miss. Smith, who would have been the first to receive news of the deaths of village boys. Robert and Ralph Dunning milled corn at Walkington Mill, some of which was supplied by the local farmers Edward Bailey, John Boynton, Edward Broomfield, William Cook,(Broadgate Farm) Alfred Carter, John Dunning, David Foster(Wolds), Mrs Gardham, Edmund Hairsine (Wolds), Harry Burrell (Lions Den), Thomas Joys, George Leaper (Manor Farm), Albert Webster (Bank Farm), Lawson Wilson (Butt Farm) the Asylum farm run by Thurlow Moses and the Mathisons at Towers Farm (later renamed Northlands farm) Poultry was raised by Fred ‘Chuck’ Richardson and John Taylor at Broadgate Cottage. At The Dog and Duck mine host was Edward Spence, at the Ferguson Fawsitt no less than three Ashtons looked after your needs and at the Barrell Inn Mary Holmes was the beer retailer. The tailor was Mr. Arthur Cross and Mr. George Sanderson and Thomas Anderson would make your boots and mend your shoes. Hannah Haldenby would take in your washing if you could afford to pay her and various ladies in the village would make their livings by dressmaking. At Walkington Hall, the Chater-Fawsitts were looked after by a cook, house keeper, a groom, and gardener John Grant and his son. Charles Marshall and George Ridsdale were joiners and most of the people living in the village would have been employed within the established businesses. The village consisted of West End, East End, Northgate and a few houses on the periphery up Kirk Lane and Townend road. There were also some outlying farms and cottages on the Risby estate. (ordnance survey map 1910 PC43/1920) Most of the families were housed in small cottages, the majority of which have been pulled down excepting for those along East End just past the Barrel Inn and in Ivy Terrace and Northgate. Domestic life was a hard graft, as lighting was by oil-lamps, water was drawn from wells, either in people’s gardens or from the well in Crake Wells. Heating and cooking was done on the fire range, and earth closets were at the bottom of the garden. Walkington was not an estate village as for example Sledmere, (although the land owned by the owners of Walkington Hall amount to 1,440 acres) so the village enjoyed a more relaxed relationship with the Chater-Fawsitts, who were known as great benefactors. In June 1914, the weather was glorious and although there had been much posturing in the Balkans and Europe, there was no thought of immediate war until the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian empire by Gavrilo Princip, a Serb sponsored terrorist on 28th June. This was neither predictable nor inevitable, yet within weeks millions of men would be on the march. Firstly Austria/ Hungary declared war on Serbia, Germany declared war on France and invaded through Belgium. Britain was committed by an earlier treaty to defend Belgium and declared war on Germany on 4th August 1914. Russia also declared war on Austria and Germany and the British Expeditionary Force went into battle on the 23rd August at Mons. Germany had a long standing strategic plan which had been developed by Alfred von Schlieffen, known as the Schlieffen Plan. (The Schlieffen Plan was the German Army’s plan for war against France and Russia. It was a direct response to the alliance between France and Russia of 1892 which was thought likely to compel Germany to fight a war on two fronts, against both her powerful neighbours in any future war. Germany planned to open the war with a massive invasion of Belgium bypassing the Maginot Line. In the event Belgium’s resistance and Britain’s immediate entry into the land war at Mons thwarted their plans and fears of Russian attacks in East Prussia diverted troops to the eastern front and diluted the German attacks). How the conflict came about and what befell millions is recorded in Max Hastings latest book ‘Catastrophe’ 2013. Of almost a hundred men from Walkington who answered the call to arms, twenty six men with Walkington connections lost their lives fighting for king and country in the 1914-18 war and are commemorated on the war memorial in Walkington churchyard. Most of these men would have known, been at school with, lived next door to or worked with each other. Some had family connections through marriage in village families. The historian A. J. P. Taylor in An Illustrated History of the War writes ‘The un-known soldier was the hero of the First World War. He vanished, except for a cipher, from written records’. As the hundredth anniversary of the First World War approached I was motivated to find out who our Walkington men were after watching the BBC production ‘The Village’ in the spring of 2013. I have spent some time during the summer adding detail to the list of the men on the war memorial. Finding the information has been an enlightening journey and I have met some interesting people, but learning of the suffering and heartbreak has been at times emotionally draining. Christine Elston November 2013 Life in Walkington during 1914 to 1919 At Walkington School classes were disrupted when Mr. Hayward went off to the front, and in 1917 the headmaster, Mr. Granger was called up. He was to serve 21 months as a signaller with the Royal Garrison Artillery batteries in France and Belgium. On his return he suffered slightly from the effects of a gas attack and from a wounded hand which affected his game of cricket. He was replaced at school by Mr. Wilfred Bilham from Sigglesthorne who boarded in Walkington during the week and went home at weekends. The school did not have a playing field, instead Mrs. Chater-Fawsitt allowed them the use of a field up Northgate known then as the deer park. This is the field which opens from the top of Northgate and runs behind the bowling green. James Thirsk in his book, ‘A Beverley Child’s War’, gives a clear description of what life would have been like for children. He tells us that popular treat foods would have been Lyles Golden Syrup and chocolate ground-rice; breakfast may have been ‘Force’ wheat-flakes and tea a boiled egg with soldiers. The games they played would have been familiar to us today like Ludo, Snakes and Ladders and rounders, but others we would be unfamiliar, a game called ‘Egg if you Move’ was probably a variation of ‘It’. Dr. Mike Scrowston in his ‘A hundred years of Education in Walkington’, tells us that on Empire Day, 24th May, the whole school paraded up to the Hall, sat on the lawn, ate chocolate bars and heard a lecture by Captain Chater-Fawsitt on Captain Cook, who he considered to be the greatest Yorkshire man of all time. The children then sang ‘Children of a Mighty Empire’, the words by Mrs. Dawe ( the rector’s wife) and music by Mr. Cammidge, organist at the Beverley Minster, and after three cheers for Mr. and Mrs. Chater-Fawsitt trooped down the drive back to school in Northgate. Professor Lythe in his Memoirs of Walkington, reprinted in the Walkington Newsletter, recalls that his father in law, Mr. S. S. Granger was in charge of the civil defence in the village. The main threat came from a sea born invasion or Zeppelins. A Zeppelin caused consternation when it appeared to be heading east from the Humber. His grandmother hauled him out of bed and took him half a mile up the road to Hunsley to get a better view! In the Beverley area Special Constables were appointed under the Special Constable Commander and Mr.Granger was ‘the’ man in Walkington. Communications were by letter, delivered by dispatch rider on a motor cycle. In ‘Our Walkington’, a publication produced by the villagers in the 1970’s Bert Griffin recalls that he joined up at the beginning of the war and during the next four years he travelled through France, Mesopotania (Iraq), Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and Egypt and apart from brief leaves did not see Walkington again until 1919. His wife, Edith Anne Curtis from Bishop Burton, lost two brothers and he lost one brother. (This could have been Ernest or Albert, as both brothers had left home before 1911 and despite finding men with the same names listed in the military for that period I could not find the essential link with Walkington that I needed). At the East Riding Asylum accommodation for wounded soldiers was provided at ‘The Ridings’, and the Medical Superintendent Dr. Archdale was absent on military duty from the outbreak of war. He returned in 1917, allowing Dr. Simpson the acting Medical Superintendent to join the 3rd Northumbrian Field Ambulance. Dr. Simpson was awarded the Military Cross for meritorious services. Miss Fielding the Matron was also released to serve with the Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Nursing Association. In addition eighteen attendants and five artisans plus the assistant clerk Mr James Robson served in the military. Mr. Haith, Mr. Robson, Mr. Reynolds, Mr. Wadsworth, Mr. Noddle, Mr. Freebury, and Mr. Brewer were all recorded as ‘sacrificed their lives for their country....in defence of The Empire’. 1915 In 1915 the country was alert for spies and Walkington became concerned as a mysterious grey car was seen going at a fast speed up the Hunsley road to set up a signal station for a ‘Zep’. (So the gossip went!) The War Office began an earnest advertising campaign in the local press for recruits. Appeals went out for ‘A National Egg Collection’ to provide for eggs for the troops who were recovering from injury. By November, Walkington had donated 1,595 eggs and this collecting was to continue for the duration. There were also weekly requests in the Beverley Guardian for cigarettes for the front and hundreds responded. Every week there are letters published from troops thanking people for their donations. The staff at the East Riding Asylum, regularly get a mention as does Miss. Ashton at The Ferguson Fawsitt Arms and Edgar Lythe who must have only been a young boy at the time. Appeals for the French, Belgian and Russian emergency funds featured regularly. So Walkington started fund raising in a big way Mrs. Chater- Fawsitt, Mrs. Dawe, Miss. Stephenson, Mrs. Joys and Miss. Plimpton led fund raising events and work parties, all the women and children set to knitting and sewing. The Beverley Guardian produced a list of comforts sent to the Walkington boys during 1915, these included 200 pairs of socks, 104 grey flannel shirts and numerous first aid articles such as bandages, swabs and towels. Ordinary life went on in other ways, the cuckoo, swallows and willow warblers arrive on the 1st May and the East Riding Ladies Golf Club continued to meet for their nine hole monthly meeting. The summer races took place at the race course at Beverley but that was the last time until the end of the hostilities, bowling and cricket continued at the Beverley recreation ground. In Walkington, the school presented an unbroken record of attendance award to Reginald Wardill and listed others for near record attendances including brothers and sisters of some of our ‘Memorial Men’, Charles Purdon, Herbert Collinson, Violet Dinsdale, Frank and Walter Lawson, and Sydney Ash. Farmers were not pleased as wheat prices dropped to 6s 6d, a cut of 13 shillings in a fortnight and flour was reduced by 18d a sack, a fall of 3s 6d in two weeks. In Risby Park, farmer Joseph Wilson was claiming £12 for the value of a heifer stolen by Walter Palmer of Hull. Weddings were taking place on a regular basis, Alfred Jackson, Royal Field Artillery of Beverley married Ada Carter from Walkington and Annie Carter married Private Ernest Widdas of 5th East Yorkshires of Beverley. The groom had been wounded in the thigh and had been in hospital in Lincoln but was due back to his regiment after the wedding. Until this time all of the men enlisting had been volunteers but after this time compulsory conscription was started. The Reverend Dawe makes his usual announcement in the Beverley Guardian that he and Mrs. Dawe would be away for the months of July and August 1915. They liked to visit the West Country each summer, and the church was reopened later in the year after internal renovation and instalment of new heating apparatus. 1916 The year 1916 found regular fund raising taking place; a new fund for the Walkington Volunteer section was started to raise money for uniforms, whist drives were a very popular event and regularly raised 33 tables. The annual meeting of the Walkington Friendly Society was reported in the Beverley Guardian where the Death and Sickness Fund stood at £116. 19s 6d, a loss on the previous year, but it did not include the profits from monies invested in a more profitable fund, the results of which were awaited. Men who had enlisted came home on leave from time to time, and we hear that Private Bert Griffin of the Seaforth Highlanders had been home after hospital care in Lincoln; also at home for a few days was Private Frank Marson, who lost his life soon after. Private G. I’Anson and Private Harold Lythe also had a few days leave. The death was announced of Mrs. Sarah Blades, wife of the late Thomas Blades of Holly Lodge, East End, mother of Gunner Jack Blades, Royal Field Artillery who had died from wounds at Rouen on 18th May 1915. His mother had lived for only a few months after receiving this news. (‘Holly Lodge’ later became the home of Louis Ashton, under the terms of the will of Major Fawsitt). Another sad death announced was that of Emily Gilbank Anderson, aged forty who was the wife of John Tom Anderson. She died following childbirth leaving ten children, one of them was Annie, mother of the well known Herdsman family of Walkington. The Parish Council had to deal with more mundane village life and payment of accounts and correspondence regarding the cost of heating, lighting and cleaning of the schoolroom during council meetings was on the agenda. July 1st,,1916 saw the beginning of the Battle of the Somme. On that first day 60,000 men were either killed or wounded for very little gain in territory. As the fighting intensified news of the deaths of Walkington men came through; the Beverley Guardian carried Rolls of Honour each week and Lance Corporal Marson was listed together with Private Duggleby, William Ash, John Haith, John Gilbank, Alan Mathison and Thomas Taylor. At this time no less than 91 men from the village were serving their King and Country. Amongst all this sad news came some good news when Captain Robert Plimpton was awarded the Military Cross. He had been a respected captain of Beverley Cricket team before the war and the club applauded his achievement. Cash prizes were presented to men of the volunteer platoon for good shooting; this took place in the reading room. In ‘Two Families at Walkington’ Professor S. G. E. Lythe outlines the benevolent acts of the Chater-Fawsitts which included the provision of a reading room. The reading room was what is now number 10 West End and because there was no social meeting place other than the public houses Mrs Chater-Fawsitt had converted a cottage and made provision for a fire and arranged daily papers. 1917 At the beginning of 1917, the Sherwood trustees met under the leadership of the Reverend Dawe and agreed to provide funds to purchase materials to be made into products needed by the Walkington men at the front. The charity fund continues to provide essential funds for a great many causes in the village, currently under the chairmanship of Mr. G. Southern. People were encouraged not to waste food and to grow their own where possible. Recipes for economical meals appeared on the women’s pages of magazines and newspapers. In Walkington, the Parish Council, was seeking land, for the provision of allotments. They instructed the parish clerk to make enquires of local landowners to see if they had land suitable for allotments as applications had been received from parishioners. The land which was eventually rented to the council by Mr. Chater-Fawsitt was situated on the north side of West End, immediately behind what is now ‘Tall Trees’, running up to Manor House Lane across the land where the manor house estate is built. The council also congratulated Mr. W. A. Plimpton on the military honours received by his three sons and applauded his younger daughter for entering hospital training; she had been with the Red Cross in France and Egypt. The minutes of the Parish Council for March 1917, include a letter sent to them by Captain Robert Plimpton, the address is ‘In a field’ and he says how he is looking forward to ‘doing my bit’ in the peaceful recuperation of farming and village life. Sadly, this was not to be as news of his death was received in September, 1917. As more and more men left for war women were encouraged to volunteer to work on the land, they were offered a uniform and advised that they could do anything men did except carry corn. The Beverley Picture House, which is now Brown’s store in Saturday Market and the Marble Arch Picture Palace which is where Marks and Spencer now stands showed patriotic films. People were encouraged to watch as one enthralling film after another was advertised each week. ‘The Battle of Ancre’ with tank battles and actual film shot at the front was used. The people of Beverley must have flocked to the cinema to see if they could spot a loved one. Worldwide, there was a great deal of unrest and in Russia the revolution forced the Tsar to abdicate. In an editorial at the time, the Beverley Guardian thought this was a mighty contribution towards the civilisation of the world. Only later would they learn of the murders of the Tsar and all his family at Ekaterinburg in 1918. Men from the village who were serving their country, continued to have leave and all are reported in the Beverley Guardian. Mrs. D. R. F. Dunning welcomed her brother Mr. J. Malcolm who was serving with an Australian contingent. Private William Richardson who had been wounded was now in a British hospital. Sargeant Jackson who had twice been wounded was reported as being on home service as was Private Windass, son-in-law of Mrs. A. Carter. Corporal Jelley (Military Medal) was also on leave for a few days after spending many weeks in hospital with dysentery. Causing as much excitement was young Fred Ash who got his fingers caught in a turnip cutter and lost the tips of two fingers; Mr. Plimpton rushed him in his car to see Dr. Munro at Beverley. Big, fit schoolboys up to the age of fifteen were encouraged to help with farm work. There is a photograph in the Beverley Guardian of twenty eight boys from the Grammar school who had volunteered to work on farms. These were outnumbered by the school cadet force which had almost twice the number. On the wider front, the help being given by America is accepted cautiously and warnings are given by editorials that money borrowed from America will have to be repaid after the war, putting our workforce under greater stress. American troops had landed in France in June 1917. Recruitment posters urged women to join the St. John Ambulance Brigade and Red Cross to work in military hospitals. An advertisement shows that women were still trying to look after their youthful looks as they were encouraged to buy ‘Ven Yusa the oxygen face cream’, to protect the face when doing war work! Gordon Armstrong who had a garage in North Bar Within, Beverley, was offering Whiting Bull Tractors for sale at £350 in his weekly advertisement, with well researched evidence that one tractor could do the work of ten horses and five men. By the following year, this same tractor was costing £395. The British Red Cross sale at Beverley raised a lot of money with Mr. J. E. Wood, farmer of Walkington, donating a mulch cow which raised £50 at auction. Walkington lost a few well known and respected residents during 1917. Mr. Harry Dolby died aged 35, in Hull Royal Infirmary; Mrs. Franklin Lambert from Waterworks House, Walkington Gate (opposite the opening to the whiting works). Mr. G. Haldenby died, he was related to the Ridsdale and the Davy families, both families had members serving in the forces. Mrs. Mary Lythe, wife of Sam Lythe (builder) died aged 70, after a long painful illness, during which her son Sydney had been wounded and treated in a hospital in France. Another brother, Sapper Harold Lythe, Royal Engineers, was also at the funeral and the third son, Ernest who owned the house we now live in (48 West End) had emigrated to New Zealand. Mr.George Ridsdale, Walkington’s oldest male resident, died aged 84. He had been born at Risby but came from an East Yorkshire family that could be traced back 200 years. George was a Primitive Methodist and Parish Councillor. He had four married sons and four married daughters. It was his nephew George Ridsdale who is listed on the war memorial. There is continuing news of serving soldiers; Rifleman T. Anderson was wounded on November 24th 1917. He lived at Woodbine Cottage (this was where no 85 East End now stands) and had been a postman before he enlisted nine months previously. There was news of the death of one of the war memorial men, Sapper Ernest Farrow, aged 24. Before the war he had been a joiner and wheelwright. Private A. Cross of the Machine Gun Corps who had been a master tailor before the war was invalided home and was in hospital in Leicester. He lived at the Red House next door to the chapel. Gunner T. Twiddle, Royal Field Artillery, from Westfield Farm was wounded and was in hospital, before joining up he had worked for Mr. T. S. Stephenson of Walkington House, Townend Road. The scholars at school were once again complimented on good attendance records and we see many familiar names amongst them including Lawrence Binnington, Maisie and Barbara Bailey, and Annie Ash. 1918 Despite the bad news which came in regularly during the year the annual round of nature continued and Mr. Taylor advertised his Rhode Island Red sitting eggs for sale, ‘satisfaction given as to fertility’. The Primitive Methodist Chapel’s musical concert was well received with many of the local children doing renditions; and the Reverend Dixon from Beverley congratulated the choir on their musical ability. Beverley aeroplane appeal raised £90,000, almost three times what had been expected, amongst the subscribers were the Chater-Fawsitts donating £100, and Mr. A. W. Waterworth from Bishop Burton who gave £1,387, and the local M.P. Captain Stanley Wilson donated £5,000. Mrs. Gardham who was selling up after farming for some years, was advertising two horses, seven beasts, six pigs and twenty four fowls as well as dairy equipment and household goods. Mrs. Gardham lived in the Sherwood house behind the pond. Her animals were probably looked after in the field which is now the bowling-green. Mr. Ridsdale was selling land at Burton Gate, lot 1 and 2 freehold and lot 3 and 4 copyhold of The Manor of Walkington and Provost Fee. Plans were made to hold the annual flag-day in aid of the After Care Colony. (This was a residential establishment for the treatment of tuberculosis (T.B.) and was situated on the road to Bishop Burton.) After the Second World War it was owned by the racehorse trainer Pat Taylor, but will be remembered by most people as the Northlands Hotel. The house and land had been donated by Sir James Reckitt to the people of Hull for the treatment of tuberculosis; he made it a condition that any person from the East Riding needing treatment was also eligible. It was recognised as one of the best in the land and the open air life it afforded the patients was widely held to be beneficial in the treatment of T.B. Residents usually stayed for one year and if necessary Hull Corporation provided for families left at home. Ex-service men were paid for by the Government, others were insured and non insured people were covered by the Hull Corporation. The colony was self sufficient and sold surplus produce making the huge amount of £70 in one year from grapes alone. News was received of the deaths of three more Walkington men at the front, Private Frank Hayton, Private Harry Ezard and Private Charles Dunn. This brought the Walkington Roll of Honour to fifteen men who had laid down their lives. In May, Private R. Binnington 1/7 Duke of Wellington’s received a card from the Rev. and Mrs Dawe as he recovers from a shell wound to his tongue and mouth. In a letter from his mother she refers to damage to his teeth and that’ it is a slow process waiting to get them done’. Later that year, the great Influenza epidemic was at its height and one hundred and seventy two inmates of the asylum (Broadgate Hospital) succumb to the virus resulting in seventeen deaths. (More lives were lost during the influenza epidemic than were lost in the Great War). The minutes of the visiting committee show that they agreed to extra pay for the nurses who had remained on duty for long hours throughout the epidemic as patients and staff succumbed to the illness. In Beverley, the local food committee issued ration books; in Parliament, the third reading of the Education Bill is passed, raising the school leaving age to 14 years. Bad news continues from the front, Private Dinsdale is reported missing during further fighting on the Somme. A letter is received from his officer Lieutenant J. R. Thompson who is reported missing himself soon after. Farm workers in Holderness go on strike for more money. They demand a minimum wage of £2 per week and £4 during harvest; farmers meet to discuss it but offer only £3.10s, so soldiers are released to help with the harvest, and the farm workers are encouraged to return to work during the arbitration period. The Beverley Guardian praises the Walkington soldiers as it reports the gaining of the Military Medal by Sergeant Edwin Oliver. Sergeant Oliver was the eldest son of Mr. and Mrs. R. Oliver who during the retreat on ‘Black Day’ during ‘The German Great Offensive’ volunteered to blow up an ammunition dump. He accomplished his mission, although he was severely wounded in the back and knee. He had previously been wounded and gassed and was progressing well in hospital in Nottingham at the time of the report. ‘Black Day’ for the Allies refers to the 21st March, 1918 when thousands of German troops smashed the allied lines and in the coming weeks pushed them back forty miles, breaking the deadlock of trench-warfare. We came close to losing the war but the ragged line held. The British, French and Americans counter attacked on 8th August, 1918 and General Ludendorf referred to this day as ‘The Black Day’ of the German army. British losses had been so severe during the Great Offensive that medical requirements and age restrictions were dropped. The tribunals then began to call up men up to the age of fifty. Corporal Reginald Jelley and Sergeant Jackson had both been awarded the Military Medal; Sergeant Edgar Drew was also amongst those decorated and was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal for bravery on the field. (He is the uncle of Dave Drew and great uncle of Jamie Drew the present chairman of the Parish Council). His younger brother had also just returned to France for a sixth time and his youngest brother in the Royal Field Artillery had been discharged with severe wounds to the head. News was received of the death of Private Tom Noddle of the Coldstream Guards. Before signing on he had been employed at the East Riding Asylum for six years. The death was also reported of Gunner W. Purdon who had been reported missing in April. The Mayor of Beverley received the official news of the armistice at Beverley Police Court at 11am, on Monday 11th November, 1918. The bells of both the Minster and St Mary’s church rang out. The shipyard was closed for the day and all other works closed down, some schools were already closed because of the flu epidemic and the streets thronged with people but few families had escaped the sorrow of bereavement created by this terrible conflict. 1919 By 1919, Mrs. Binnington is writing to her son Robert as he looked forward to being demobbed, she told him what was happening in the village ‘that Harold Lythe is now back playing the organ at church and it had been a lovely Michaelmas summer’. She says. ‘We have finished with plums and damsons and your dad got the apples pulled and all the potatoes up, we have a good stack of onions so you will find plenty to go at, she finishes by hoping that the strike will soon be over.’ It is difficult to pinpoint the exact strike she was referring to but there was considerable unrest in the immediate post war years with police, miners, dock workers, engineer, railway workers, transport workers and farm workers going on strike. It was the nearest Britain ever came to a workers revolution. British workers, like those all over Europe, strained to overthrow the capitalist system but were dragged back at a rally in the Albert Hall, in October 1919 when it was conceded that the workers revolution was not ready to overthrow the Government. Wage negotiations after this time would be within the capitalist system. But as the news starts to come through of the atrocities being committed by the Bolsheviks against their own people, many would be glad that this country did not go down the communist road. Whilst reading the Beverley Guardian for 1919 I have eagerly looked down the list of wounded and can only imagine the hope in people’s hearts as they searched for loved ones who had been reported missing. None of the boys on the Walkington Memorial were amongst the list but many were listed in the ’in memoriam’ columns. One from M. Lewis for George Boynton says ’noble and faithful to the end’. There was also one from Harry Ezard’s young widow Mabel, ‘Still memory clings’. One Walkington wife, Mrs. Doris Davey nee Ridsdale was delighted to hear from the Red Cross that her husband was alive and had been a prisoner of war. The family still have this communication preserved in the family Bible. Towards the end of the year Walkington Church celebrates a pretty wedding when Miss. Maggie Twiddle from Westfield Farm, marries Arthur Baker and they go to live at Wold Farm.( this is the farm up passed Middlehow pit(now Remembrance Wood).Her brother Thomas, was wounded earlier in the war and had returned home for the celebrations. Peace celebrations were held and the Parish council paid for teas for the whole village. The photograph taken of residents in Northgate shows the relief and joy. Northland farm was bought by one Mr. A. H. Waterworth; Mr. A. Stanley Wilson is returned as the coalition M.P. under the leadership of Mr. David Lloyd George. Mr. H. R. Pease, the agent at Bishop Burton estate, was voted in as the local County Councillor and women demand equality through the Union of Women Suffrage Society. Life in Walkington was a microcosm of the changing times. The Chater-Fawsitts were about to sell Walkington Hall and their land. Tractors were replacing men on the farms, women were beginning to fight for universal suffrage and the right to work. Men were demanding a fair wage and Walkington is about to enter a new phase in the life of the village. During the hundred years since the end of the First World War the country has experienced all of the emotions associated with grief, shock, denial, anger, guilt, blame, and a striving to understand why. We have had the reflections and analysis of hundreds of historians and biographers and heard the voices of the men who took part. Today we can only imagine the life and times of those who lived through it. Nevertheless here in Walkington we thrive, life here is satisfying, we are surrounded by beautiful well tended country side. The village activities continue and unless our way of life is threatened the coming generations will continue to make Walkington home. The British Army in 1914 In August 1914, Field Marshall Lord Kitchener dismissed the prevailing view that the war would be ‘over by Christmas’ and announced his intention to raise five new armies, 500,000 men. Each army would be in the image of the British Expeditionary Force that had been sent to fight alongside the French as the Germans invaded Belgium. Volunteers came forward in unprecedented numbers, causing an immediate shortage of equipment and experienced officers to train recruits into soldiers. For the first of these new armies, known unofficially as K1 and K2 the problems were soon rectified but with K3, K4 and K5 the problems of inexperienced officers became critical. Shortages of uniforms and equipment and the inability to get troops quickly into place increased the problems of the senior officers. Communications between the allies was at times almost non-existent and troops were often moved without any knowledge of what was happening in other parts of the line. The ordinary soldier had quickly to learn that these armies were made up of two or three Corps which comprised two or three Divisions (15,000 to 20,000 men). A British Division had three Brigades, these Brigades were made up of four Battalions and each battalion had four Companies of two hundred men. A Company consisted of four Platoons and these would be the pals you trained with and fought along- side. Stages of the war Phase I: The German Invasion of Belgium, August 1914. As the British Expeditionary Force fulfilled their pledge to protect Belgium from invasion, two of our Walkington men who had been regular soldiers were preparing to embark for France. Daniel Reynolds, a past regular soldier in the King’s Royal Rifle Corp would be the first Walkington man to lose his life as the troops dug in to try to protect the town of Armentieres, on the French/ Belgium border. He died on 2nd November, 1914. Meanwhile, Timothy Oliver had been recalled from the Durham Constabulary to service in the Coldstream Guards. He would have said goodbye to his wife Jane, and three young children expecting to be home for Christmas; he died on Christmas Day, following the successful defence of the village of Givenchy. One can only speculate on the scene at his home in West Hartlepool as his wife received the telegram and relayed the news to his family in Walkington. Both of these men were awarded the 1914/15 Star with bar to denote they had been in the front line. The spontaneous truce that happened along the lines between German /French, German/British, German/Russian and Austrian /Russian troops at Christmas 1914 allowed the dead to be buried peacefully, amongst these was Timothy Oliver. In one instance between the German/ British troops the Germans actually carried the British dead to the middle of ‘no man’s land’. During this first phase of the war the French, British and Belgium troops had conducted a dogged defensive battle in which they were just able to hold the line against heavy odds. Total British casualties from September to December 1914 were 89,964. Phase II: Trench Warfare 1915. As spring gave way to summer, by 1915 the troops were dug in for trench warfare. At the beginning of 1915 the trenches on both sides were defended by swathes of barbed wire, sometimes four lines deep. They were designed to be impenetrable, protecting both fronts from infantry attack. A series of lines stretched from the English Channel to Switzerland. The trenches were a vast network of sophisticated dugouts where soldiers lived and worked. Both sides planned and executed attacks on each other trying to gain ground. Over the course of the next four years, yards and sometimes miles would be gained and then lost again. Our next Walkington man, John Blades, was to die as the town of Ypres was defended for a second time on 12th May 1915. At these second battles of Ypres the Germans used chlorine gas for the first time. Phase III: The Allied Offensive (Operations on the Somme). By 1916, the French were suffering enormous casualties at Verdun and pleaded with the British to attack on the Somme in order to relieve German pressure on Verdun. The Allied Offensive which was the Operations on the Somme took place between 1st July and 18th November 1916; these bloody battles were to claim 170,182 lives, amongst them six Walkington men. In the build up to the battle before the men went ‘over the top ’in ‘The Big Push’ the German lines were bombarded with thousands of tons of shells. The British Generals believed that this barrage would have flattened the German trenches and they told the men to go over the top and walk slowly towards the German lines which they expected to be empty. This proved not to be so and the German machine guns opened up and mowed down the British forces. On this first day 20,000 men were killed, and 40,000 wounded, the heaviest loss by British forces in a single day. Morale had been high before this battle, afterwards the soldiers began to understand what they were up against. Firstly, Frank Marson of the 8th East Yorks., was killed, then John Gilbank in the Notts. and Derbys. (The East Yorkshire Regiment took a particular battering), Harry Duggleby 8th East Yorks., Alan Mathison 1st East Yorks., Thomas Taylor 1st East Yorks, William Ash 1st East Yorks., and finally John Haith 3rd Coldstream Guards all gave their lives in this terrible slaughter. The men had been under constant barrage from heavy guns with gas attacks increasing the living nightmare. Barrie Barnes describes the horrors in his book ‘This Righteous War’ as recalled by the men of the East Yorkshire Regiment ‘Hull Pals’. Harold Ashton who had emigrated to South Africa may have been involved in the battles around Delville Wood on the Somme in 1916. If he was he survived, not dying until 1918. The families of all these men and others who died, would have received an illuminated scroll and memorial plaque or death penny, plus medals: ‘He whom this scroll commemorates was numbered amongst those who, at the call of King and Country, left all that was dear to them, endured hardness, faced danger, and finally passed out of sight of men by the path of duty and self sacrifice, giving up their own lives that others might live in freedom. Let those who come after see to it that his name be not forgotten.’ The 1914 Star and Bar was awarded to all men who had been in action from 5th August to 22nd November 1914. Those who were in France between those dates but saw no action got the 1914 Star but no Bar, these men were members of the original British Expeditionary Force or ‘Old Contemptibles’. The 1914-15 Star was awarded to men who saw active service after 1914 up to the end of 1915. Men who enlisted in or after 1916 never got a Star, all would get the War Medal and Victory Medal. The length of the front line being defended by the British Army began to stretch from 25 miles in 1914 to over 123 miles by 1918. Nearly 5,000 miles of railway tracks were laid to carry the vast amounts of war materials from dockside to railheads. Great use was also made of the canal systems in Northern France for moving supplies. Phase IV: Advance to the Hindenburg Line. By the end of 1916 the Front was advancing to the Hindenburg line. The Hindenburg Line had been strategically placed by the German high command, and prepared unmolested by allied troops, it was a forty mile defensive wall made up of trenches and barbed wire designed to defend Germany from an anticipated increase in the Anglo- French attacks. The Germans believed it was impregnable. The British Offensives of 1917/18 proved otherwise. Phase V: The Allied offensive (3rd Ypres) Passchendaele 1917. The offensive continued throughout 1917,The Battle of Arras in April/May, The Battle of Messines Ridge, June 1917; 3rd. Ypres July/ November and Cambrai, December 1917. Robert Plimpton, the only officer named on the Walkington memorial was to lose his last fight on 27th September 1917. He was awarded the Military Cross and Bar. Ernest Farrow was involved in the push towards Cambrai when tanks were successfully used to breach the Hindenburg line. Despite breaching the line the capture of Cambrai from the enemy could not be achieved. Ernest Farrow lost his life during the retreat after this unsuccessful attack on Cambrai. (The Military Cross was awarded to officers and non commissioned officers (N.C.O.) in appreciation of distinguished and meritorious service in time of war. Bars were added for subsequent awards.) Despite the Royal Navy having command of the high seas much shipping was lost due to enemy action, although this was not the cause of the loss of our two Royal Navy men. Stoker Albert Collinson, who was serving as a stoker in the Royal Navy, lost his life on 9 July, 1917, on board H.M.S. Vanguard, not through enemy action but through a probable fault in the design of the ship when cordite combusted causing an explosion which ripped through the ship as it manoeuvred off Scapa Flow. He drowned together with 900 of the ship’s crew. Another Royal Navy man Able Seaman George Boynton was also lost when his ship, H.M.S. Narbrough broke up and sank as it went to the assistance of H.M.S. Opel, off the Orkneys on 12th January, 1918. Phase VI: The German offensive 1918. As the Germans continued their final offensive from March through to June 1918, nine more Walkington men were to sacrifice their lives. These men were Private Fred Dinsdale, Private Charles Dunn, Private Harry Ezard, Gunner Walter Purdon, Private Harry Lawson, Private John Cross and Private Frank Hayton. The men were weary after two years of attacking German lines only to be thrown back almost forty miles with heavy casualties. At this stage we came very close to losing the war. Phase VII: Advance to Victory. Finally on 8th August, 1918 the armies began their advance to victory; they would again fight over the land of the Somme. The war of attrition which had lasted four years was over. Private Tom Noddle would survive almost to the end of the war but was killed with the end in sight on 27th August, 1918. Harry Wadsworth who had been suffering from tuberculosis would die at home in 1918, and Gunner George Ridsdale would also die at home in 1919 from the results of being gassed earlier in the war. Trooper Harold Ashton would die in far away Johannesburg as he waited for demobilisation The armistice was signed at 5a.m. on 11th November, 1918. At 11am that morning the fighting stopped. On 18th January, 1919 The Peace Conference assembled in Paris and the peace treaty was presented to the Germans in May, 1919. The formal signing of the treaty was signed in the Hall of Mirrors in Versailles in June, but there was much tidying up to be done in the rest of Europe. Some decisions would contribute to the Second World War, but that is another story. In the final chapter of his latest book ‘Catastrophe’, Max Hastings analyses the outcomes of the war, it is recommended reading for anyone wanting to understand why the war happened and why it was so important for the western allies to be successful. Acknowledgements I would like to thank all the relatives and people living in Walkington who have given information about family members or knowledge passed down from families. Jean Wilson (Willie Ash), Eileen Archibald (George Boynton), Brenda Wilson (Albert Collinson), John Cross (Jack Cross), Graham Huntley (Frank Hayton), Judy Smith (Frank Marson), Elizabeth Foster (Tim Oliver), Trevor Purdon (Walter Purdon), Stuart Lace (George Ridsdale). Peter Rainer who took the new photographs in the churchyard, Shirley Scrowston, for the loan of books and her father’s medals, Amy Tomlinson for the loan of books, Bryan Watson for his knowledge of Walkington, Lucy Drew for the original photographs taken when the Memorial was dedicated. My particular thanks go to the historian Barrie Barnes who has guided me through all the information available about the Great War and the staff of the Treasure House, Beverley, their efficient service helped me find all the information I was looking for. I would also like to thank John Bowe for his interest in the Great War, helpful advice and for correcting my English, Mr Jamie Drew and members of the Walkington Parish Council for allowing me to use photographs from the archives and to Mr George Southern chairman of the Sherwood and Waudby Charity who encouraged me to carry on after reading and advising on the original work. The project has been funded by Walkington Parish Council and the Sherwood and Waudby Trust for which I am very grateful. The Researcher Christine Elston has lived in Walkington for the past sixty five years having moved from Beverley with her parents Ernie and Doris Teal and her sister Pat just after the 2nd World War. She is married to John and has two daughters and two grand children. She grew up alongside the descendants of some of the men on the war memorial and has provided an account for the current residents of the village on the happenings in the village at the beginning of the Great War and of the men who gave the ultimate sacrifice for us all. Christine trained first as a general nurse and secondly as a psychiatric nurse at Broadgate hospital and had a nursing career spanning four decades.