* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Writer`s Workshop

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

E. Harlos

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

Whenever there are questions that you need to complete they will have a small

number in brackets at the end of them.

Ex:

What is your favorite colour? (1)

This number is the value of marks this question is worth. You need to write AT

LEAST that many points or sentences. Writing MORE than necessary is always

preferred in case you are a little off on one of your points.

When you answer questions you want to EXPLAIN

DESCRIPTION.

WHY using

Ex:

One of my favorite colours right now is brown. I am really into brown clothing. I love

to wear chocolate brown and so does my daughter! She’s only 2 years old so I guess she has to

like it as I buy all of her clothes!

You do not need to write out the questions… however your answer should

CONTAIN the question in a full

sentence. Avoid using yes (or no) to

answer your questions – write out what you mean.

Ex:

Do

Do you like the show Corner Gas?

NOT do this:

Yes, it’s a good show.

DO: I do like the show Corner Gas because I like the distinctly Canadian humour. I can

relate to the show because I am from the prairies just like the characters on Corner Gas.

The “do not: example” above is a SENTENCE FRAGMENT. You want to avoid

writing sentence fragments. Sentence fragments are missing some key

information. To avoid sentence fragments make sure all of your sentences can

make sense standing alone. That is, if you separate them from the rest of your

writing they still make sense

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

- sentence fragments –

Working on avoiding sentence fragments:

When writing, it is important that all of your sentences can stand alone.

Short sentences can not. You want to avoid sentence fragments. That don’t have

enough information. We will work on sentence fragments here. To make sure you

learn how to avoid them.

I have underlined the sentence fragments in the above writing…do you see that

alone they do not make sense?

Short sentences can not. (can not do what?)

That don’t have enough information (what don’t?)

To make sure you learn how to avoid them. (avoid what?)

To fix sentence fragments, either combine sentences or add additional information

to the fragments:

When writing, it is important that all of your sentences can stand alone

because short sentences can not. You want to avoid sentence fragments that don’t

have enough information. We will work on sentence fragments here, to make sure

you learn how to avoid them.

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

- sentence fragments –

Underline the sentence fragments in the following pieces of writing. Then rewrite the piece without the fragments.

1.

This morning I slept in. If you could call it that. I like to get up early, so

7am is

sleeping in for me. I like to start the day with coffee. Milk in it.

Drinking my coffee.

Watching the news. My favorite way to start the day.

2.

I hear the backstreet boys are getting back together. What a surprise. I

guess they were popular in their day. Although not to me.

3.

Are you getting what sentence fragments are? How to fix them? How to

avoid them? They are the sentences. That can’t stand alone.

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

-commonly mis-used wordsIn the English language unfortunately we have a number of words that are the same but not the same. They

SOUND the same but they are not the same WRITTEN word.

its / it’s

Its is a personal pronoun in the possessive form. The dog wagged its tail.

It’s is a contraction of it is. It’s a sunny day today.

there /their /they’re

There indicates a place and is the opposite of here. Over there!

Their is the possessive form of they. Their school work.

They’re is a contraction of they are. They’re good students.

to / too / two

To is a preposition. It is also an infinitive, a verbal. The road to freedom.

Too is an adverb that means “also” or “overly”. It was too spicy.

Two refers to the number. There were two computers.

your / you’re

Your is the possessive form of the pronoun you. Your work.

You’re is the contraction of you are. You’re improving your writing.

accept / except

Accept is a verb that indicates agreement. I accept your invitation.

Except a preposition that means excluding. Everything except apples.

affect / effect

Affect is a verb meaning to have influence or to act on emotions.

Seeing her always affects me.

Effect can be a verb or a noun. As a noun it can mean a result (side

effects) or belongings (her personal effects) or give an impression (he has

that effect on me). As a verb, effect can mean to bring about (I want to

effect change)

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

-commonly mis-used words-

1.

Its/It’s a nice sunny day today.

2.

The cat stretched its/it’s legs.

3.

Go over there/their/they’re now!

4.

There/their/they’re going to get married in the summer.

5.

It is going to be there/their/they’re special day.

6.

I am going to/too/two outside for a walk.

7.

Let me go to/too/two!

8.

So, there are to/too/two of us going on a walk.

9.

Your/you’re writing is going to be great someday!

10.

Your/you’re improving every day.

11.

I am taking all of my clothing on the holiday, accept/except my winter

coat.

12.

I can’t wait to let him know that I accept/except his invitation.

13.

Reading that book really had an affect/effect on me.

14.

It is a side effect/affect of the medication.

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

-another commonly mis-used word-

ALOT

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

- COMMAS –

A comma indicates a slight pause in a sentence.

Ex:

Before students finish this class, they will learn how to write

like pros!

You try:

1. As you go through these exercises you will get better at writing.

A comma is used to separate words or groups of words within a complete thought.

Ex:

He picked up the pennies, nickels, and dimes.

Ex:

It took all day to separate the coins, count them up, and put

them in their paper rolls.

You try:

2.

Go to the grocery store and buy apples oranges and bananas.

3.

When you get home slice the apples peel the oranges and mash

the bananas.

Use a comma after an introductory word or phrase.

Ex:

You try:

4.

In 2003, there were 300 cars sold.

After grace we ate the meal.

Use a comma to separate two or more adjectives (describing words) that come

before a noun.

Ex:

You try:

5.

Vancouver is a large, beautiful city.

Alice is a shy quiet girl.

Use a comma before but, nor, or, for, so, yet when it joins two separate thoughts.

Ex:

The sky was dark and cloudy, but the sun was still out.

Ex:

The kid must get to bed early, or they will be tired in the

morning.

You try:

6.

I feel happy today yet I am unable to show it.

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

- COMMAS –

The following piece of writing has no commas in it. Add commas where

necessary.

Once upon a time there was a cute precious puppy named Mojo. She was

always ready to fetch a ball play tug-o-war or chew on a toy. One day in

September Mojo got out of the fence and ran down the street. Luckily a

neighbour found Mojo put a leash on her and brought her home. It scared Mojo

to be outside of the yard yet she enjoyed the run! Thankfully Mojo is learning

the rules these days. She is calming down listening to her owners and being a

pleasant friendly dog.

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

- OTHER PUNCTUATION –

Colons

Use a colon before a list of items.

Ex:

For the football game, I’ll need to have the following: snacks, pizza,

diet pop, and licorice.

Use a colon after the salutation of a letter.

Ex:

To whom it may concern:

You try

1.

Dear Sam

2.

I have to go to the mall at lunch to buy the following pens, pencils,

and staples.

paper,

Semicolons

Use a semicolon when you are joining two complete sentences that share a similar

thought.

Ex:

One important crop in the West is canola; it is grown for its oil.

You try:

3.

It was a fun day at the beach the sun was hot and the lake was

calm.

Apostrophes

Use apostrophes to show possession.

Ex:

Ava’s toys

Erin’s module

Use an apostrophe to create a contraction.

Ex:

I am = I’m

can not = can’t

You try

4.

I am excited to read Taras assignment.

we are = we’re

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

- PUNCTUATION –

Add punctuation to the following piece of writing:

On Sunday Darian and Patrick went walking to the park. When they arrived they

couldnt decide what to do they sat for awhile to think it over. Once they had

agreed on a game plan they decided on the following ride the teeter toter play in

the sand and end with some swinging. After they finished all of that Darian

discovered that Patricks shirt was ripped. Since neither boy knew how to sew

Darian and Patrick headed for home.

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

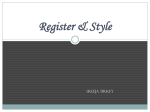

FORMAL LANGUAGE Versus INFORMAL LANGUAGE

There is a large difference between writing a text to

someone and writing an essay in University. Certain words

are appropriate in certain situations and not others. In

academic writing, you will be asked to use formal language

in certain situations and informal language in others. Here

is some info on the difference.

INFORMAL LANGUAGE

Can include:

slang or even swears when appropriate

contractions

abbreviations (T.V.)

numbers (1 instead of one)

personal words or phrases like I, you, we

FORMAL LANGUAGE

Excludes:

slang or even swears when appropriate

contractions

abbreviations (T.V.)

numbers (1 instead of one)

personal words or phrases like I, you, we

Writer’s Workshop

learning to be a better writer

FORMAL LANGUAGE Versus INFORMAL LANGUAGE

Decide whether this language is informal (I) or formal (F).

1.

sup?

2.

can’t

3.

will not

4.

I am going to…

5.

The students worked…

6.

r u goin?

7.

LOL

8.

watching TV

9.

The teacher had 4 books to read.

10.

I am going to write about…

The Writing Process

Step 1

Prewriting is a technique for gathering ideas. Pre-writing starts by

just getting your ideas down on paper. Your only focus here is to

generate ideas; to brainstorm… write down whatever comes to

mind about your topic.

Step 2

During drafting your focus is to get your ideas into the assigned

format. Don’t worry about grammar, spelling, etc. here you are

just ordering your ideas and organizing them into a desired

format.

Step 3

During revising you will read through your draft and revise. Circle

things, cross out stuff, add etc. Do whatever you need to do to

“FIX” your writing until it is error free. Edit, proofread and polish!

DO THIS ON YOUR DRAFT- you do not need to re-write it – yet!

Once you have completed your own revisions, get a friend, family

member or teacher to revise and edit for you.

Step 4

Now write or type out a FINAL DRAFT and hand it in. Just before

you does this take a quick look at how you are being evaluated

and be sure you have met all of the criteria.

Types of Writing

Personal

A piece of writing designed to talk about the author’s personal experience, feelings or

ideas

Expository

A piece of writing designed to inform, explain and describe

Persuasive

A piece of writing designed to convince or persuade

Narrative

A piece of writing designed to tell a story

Descriptive

A piece of writing designed to describe an observation or experience

Researched

A piece of writing based on discovered facts through ample investigation

Types of Writing Crossword

1

2

3

4

5

6

ACROSS

DOWN

4. talks about the author’s

personal experience, feelings

or ideas

6. based on discovered facts

through ample investigation

1. informs, explains and

describes

2. designed to convince or

persuade

3. tells a story

5. describes an observation or

experience

Writing A PARAGRAPH

Your paragraph should begin with a

TOPIC SENTENCE: this is a sentence

that explains what your paragraph is about.

The BODY of your paragraph explains your

topic sentence: use examples and

description to explain what you mean in 5-8

sentences. Your paragraph should end with

a CONCLUDING STATEMENT: this is a

sentence that sums up everything you have

discussed in your paragraph.

WRITING AN ESSAY

Essays are OPINION pieces that use FORMAL LANGUAGE.

Typically an essay is a persuasive piece designed to answer a posed essay

question. Your goal is to convince a reader to buy into your ideas by offering

well articulated proof and justification for your opinion.

Work your way through this process to learn how to write an essay.

Essay question:

Step 1

Brainstorm (pre-write) ideas as to how you will answer this question and

WHY.

Step 2

Pick the best THREE reasons you came up with for why your opinion is

true.

Step 3

Construct your THESIS STATEMENT

What is a THESIS STATEMENT?

A thesis is your answer to the posed essay question. It

contains your opinion and THREE reasons why your answer is correct.

Template:

________________________________________ because

_______________________________, _____________________________________, and

_________________________________________.

Step 4

Separate the three points from your thesis and begin to brainstorm ideas

and examples to PROVE they are true.

Point 1

Point 2

Point 3

Step 5

Take each point and create ONE sentence that sums up what you have to say

about it. These will become TOPIC SENTENCES. The ideas and examples

from above will form the rest of the paragraph.

Point 1

Point 2

Point 3

Step 6

Begin to write your INTRODUCTION.

Your introduction should look like a funnel

ending narrow.

beginning broad and

Begin your intro with GENERAL STATEMENTS about the TOPIC. Next

begin to narrow your in on your opinion. Lastly, end your intro with your thesis.

General statements about the topic

Narrowing statement(s)

Thesis

Step 7

Begin to write your CONCLUSION.

Your conclusion should look like a reverse funnel

and ending broad

beginning narrow

Start by restating your thesis (use slightly different phrasing). Next review your

points and lastly, EXPAND -- THINK BIG and answer SO WHAT? WHO

CARES?

Restated Thesis

Review of points

Expand, think big… answer so what? Who cares?

Step 8

Put all of your pre-writing into a 5 paragraph formal essay.

Intro Paragraph (pre-writing from page 4)

Body Paragraph One (pre-writing from page 3)

Body Paragraph Two (pre-writing from page 3)

Body Paragraph Three (pre-writing from page 3)

Concluding Paragraph (pre-writing from page 5)

Step 9

Revise, Revise, Revise!

Read through your essay and fix it up. Ask yourself these questions:

□ Is your thesis clear and in the right place?

□ Do you have 5 paragraphs (intro, 3 body paragraphs, conclusion)

□ Do you use only formal language?

□ Do each of your body paragraphs begin with a topic sentence?

□ Is your intro a funnel?

□ Is your conclusion a reverse funnel?

□ Spelling, grammar errors?

□

□

Step 10

Have someone else proof-read your draft.

Step 11

Write on and hand in a FINAL DRAFT.

Formatting your Writing

Please type your work. Hand-writers tended to have more spelling, punctuation, and

little grammar errors that a computer spell and grammar check would fix for you.

Always title your work. Be creative and go beyond Paragraph, Essay or Final Draft

please. Your title should be centred, the same size font, and underlined.

“Glee”: The Show you Should Never Miss

Double space your work. This makes your work easier to read and leaves space for

feedback and revision.

All of your work should be formatted EXACTLY like this:

Your first and last name

The class you are in

The date it is submitted

Your’s teacher’s name

size 12, Times New Roman Font

Top left hand corner, single spaced in regular body of your work (not a header)

Sue Sylvester

Social Studies

September 1, 2011

Ms. Harlos

Glee: The Show you Should Never Miss

Blah, blah, blah and blah and the double space this work.

Code for how I write on your work:

Also

gdleave

= good

an extra space after each paragraph.

vgd = very good

SF= sentence fragment

AWK = awkward; sounds weird

P = paragraph

WW = wrong word

WP = wrong punctuation

RO= run on sentence

If something is circled there is something wrong with it (i.e. it is informal, it is

capitalized wrong, it is spelled wrong…)

APA Format says:

Italicize or underline the titles of longer works such as books, edited collections, movies,

television series, documentaries, or albums: The Closing of the American Mind; The Wizard of

Oz; Friends.

Put “quotation marks” around the titles of shorter works such as journal articles, articles

from edited collections, television series episodes, and song titles: "Multimedia Narration:

Constructing Possible Worlds"; "The One Where Chandler Can't Cry."

Attending to Grammar

A Brief Introduction

Grammar is more than just a set of rules. It is the ever-evolving structure of our

language, a field which merits study, invites analysis, and promises fascination.

Don't believe us? Didn't think you would.

The fact is that grammar can be pretty dull: no one likes rules, and memorizing rules is

far worse than applying them. (Remember studying for your driver's test?) However, as

I've said, grammar is more than this: it is an understanding of how language works, of

how meaning is made, and of how it is broken.

You understand more about grammar than you think you do. Brought up as English

speakers, you know when to use articles, for example, or how to construct different

tenses, probably without even thinking about it. (Non-native speakers of English may

struggle with these matters for years.)

However, when you write, even as a native speaker of English, you will encounter

problems and questions that you may not know how to answer. "Who" or "whom?"

Comma or no comma? Passive, or active?

Most Commonly Occurring Errors

Would grammar seem more manageable to you if we told you that writers tend to make the same twenty

mistakes over and over again? In fact, a study of error by Andrea Lunsford and Robert Connors shows

that twenty different mistakes constitute 91.5 percent of all errors in student texts. If you can

control these twenty errors, you will go a long way in creating prose that is correct and clear.

Below is an overview of these errors, listed according to the frequency with which they occur. Look for

them in your own prose.

1. Missing comma after introductory phrases.

For example: After the devastation of the siege of Leningrad the Soviets were left with

the task of rebuilding their population as well as their city. (A comma should be placed

after "Leningrad.")

2. Vague pronoun reference.

For example: The boy and his father knew that he was in trouble. (Who is in trouble?

The boy? His Father? Some other person?)

3. Missing comma in compound sentence.

For example: Wordsworth spent a good deal of time in the Lake District with his sister

Dorothy and the two of them were rarely apart. (Comma should be placed before the

"and.")

4. Wrong word.

This speaks for itself.

5. No comma in nonrestrictive relative clauses.

Here you need to distinguish between a restrictive relative clause and a nonrestrictive

relative clause. Consider the sentence, "My brother in the red shirt likes ice cream." If

you have TWO brothers, then the information about the shirt is restrictive, in that it is

necessary to defining WHICH brother likes ice cream. Restrictive clauses, because they

are essential to identifying the noun, use no commas. However, if you have ONE

brother, then the information about the shirt is not necessary to identifying your

brother. It is NON-RESTRICTIVE and, therefore, requires commas: "My brother, in the

red shirt, likes ice cream."

6. Wrong/missing inflected ends.

"Inflected ends" refers to a category of grammatical errors that you might know

individually by other names - subject-verb agreement, who/whom confusion, and so on.

The term "inflected endings" refers to something you already understand: adding a

letter or syllable to the end of a word changes its grammatical function in the sentence.

For example, adding "ed" to a verb shifts that verb from present to past tense. Adding an

"s" to a noun makes that noun plural. A common mistake involving wrong or missing

inflected ends is in the usage of who/whom. "Who" is a pronoun with a subjective

case; "whom" is a pronoun with an objective case. We say "Who is the speaker of the

day?" because "who" in this case refers to the subject of the sentence. But we say, "To

whom am I speaking?" because, here, the pronoun is an object of the preposition "to."

7. Wrong/missing preposition.

Occasionally prepositions will throw you. Consider, for example which is better:

"different from," or "different than?" Though both are used widely, "different from" is

considered grammatically correct. The same debate surrounds the words "toward" and

"towards." Though both are used, "toward" is preferred in writing. When in doubt, check

a handbook.

8. Comma splice.

A comma splice occurs when two independent clauses are joined only with a comma.

For example: "Picasso was profoundly affected by the war in Spain, it led to the painting

of great masterpieces like Guernica." A comma splice also occurs when a comma is used

to divide a subject from its verb. For example: "The young Picasso felt stifled in art

school in Spain, and wanted to leave." (The subject "Picasso" is separated from one of its

verbs "wanted." There should be no comma in this sentence, unless you are playing with

grammatical correctness for the sake of emphasis - a dangerous sport for unconfident or

inexperienced writers.)

9. Possessive apostrophe error.

Sometimes apostrophes are incorrectly left out; other times, they are incorrectly put in

(her's, their's, etc.)

10. Tense shift.

Be careful to stay in a consistent tense. Too often students move from past to present

tense without good reason. The reader will find this annoying.

11. Unnecessary shift in person.

Don't shift from "I" to "we" or from "one" to "you" unless you have a rationale for doing

so.

12. Sentence fragment.

Silly things, to be avoided. Unless, like here, you are using them to achieve a certain

effect. Remember: sentences traditionally have both subjects and verbs. Don't violate

this convention carelessly.

13. Wrong tense or verb form.

Though students generally understand how to build tenses, sometimes they use the

wrong tense, saying, for example, "In the evenings, I like to lay on the couch and watch

TV" "Lay" in this instance is the past tense of the verb, "to lie." The sentence should

read: "In the evenings, I like to lie on the couch and watch TV." (Please note that "to lay"

is a separate verb meaning "to place in a certain position.")

14. Subject-verb agreement.

This gets tricky when you are using collective nouns or pronouns and you think of them

as plural nouns: "The committee wants [not want] a resolution to the problem."

Mistakes like this also occur when your verb is far from your subject. For example, "The

media, who has all the power in this nation and abuses it consistently, uses its influence

for ill more often than good." (Note that media is an "it," not a "they." The verbs are

chosen accordingly.)

15. Missing comma in a series.

Whenever you list things, use a comma. You'll find a difference of opinion as to whether

the next-to-last noun (the noun before the "and") requires a comma. ("Apples, oranges,

pears, and bananas...") Our advice is to use the comma because sometimes your list will

include pairs of things: "For Christmas she wanted books and tapes, peace and love, and

for all the world to be happy." If you are in the habit of using a comma before the "and,"

you'll avoid confusion in sentences like this one.

16. Pronoun agreement error.

Many students have a problem with pronoun agreement. They will write a sentence like

"Everyone is entitled to their opinion." The problem is, "everyone" is a singular

pronoun. You will have to use "his" or "her."

17. Unnecessary commas with restrictive clauses.

See the explanation for number five, above.

18. Run-on, fused sentence.

Run-on sentences are sentences that run on forever, they are sentences that ought to

have been two or even three sentences but the writer didn't stop to sort them out,

leaving the reader feeling exhausted by the sentence's end which is too long in coming.

(Get the picture?) Fused sentences occur when two independent clauses are put

together without a comma, semi-colon, or conjunction. For example: "Researchers

investigated several possible vaccines for the virus then they settled on one"

19. Dangling, misplaced modifier.

Modifiers are any adjectives, adverbs, phrases, or clauses that a writer uses to elaborate

on something. Modifiers, when used wisely, enhance your writing. But if they are not

well-considered - or if they are put in the wrong places in your sentences - the results

can be less than eloquent. Consider, for example, this sentence: "The professor wrote a

paper on sexual harassment in his office." Is the sexual harassment going on in the

professor's office? Or is his office the place where the professor is writing? One hopes

that the latter is true. If it is, then the original sentence contains a misplaced

modifier and should be re-written accordingly: "In his office, the professor wrote a

paper on sexual harassment." Always put your modifiers next to the nouns they modify.

Dangling modifiers are a different kind of problem. They intend to modify something

that isn't in the sentence. Consider this: "As a young girl, my father baked bread and

gardened." The writer means to say, "When I was a young girl, my father baked bread

and gardened." The modifying phrase "as a young girl" refers to some noun not in the

sentence. It is, therefore, a dangling modifier. Other dangling modifiers are more

difficult to spot, however. Consider this sentence: "Walking through the woods, my

heart ached." Is it your heart that is walking through the woods? It is more accurate

(and more grammatical) to say, "Walking through the woods, I felt an ache in my heart."

Here you avoid the dangling modifier.

20. Its/it's error.

"Its" is a possessive pronoun. "It's" is a contraction for "it is."

Attending to Style

Introduction

Most of us know good style when we see it. We also know when a sentence seems

cumbersome to read. However, though we can easily spot beastly sentences, it is not as

easy to say WHY a sentence - especially one that is grammatically correct - isn't working.

We look at the sentence; we see that the commas are in the right places; we find no error

to speak of. So why is the sentence so awful? What's gone wrong?

When thinking about what makes a good sentence, it's important to put yourself in the

place of your reader. What is a reader hoping to find in your sentences? Information,

yes. Eloquence, surely. But most important, a reader is looking for clarity. Your reader

does not want to wrestle with your sentences. She wants to read with ease. She wants to

see one idea build upon the other. She wants to experience, without struggling, the

emphasis of your language and the importance of your idea. Above all, she wants to feel

that you, the writer, are doing the bulk of the work, and not she, the reader. In short, she

wants to read sentences that are forceful, straightforward, and clear.

The Basic Principles of the Sentence

Principle One: Focus on Actors and Actions

To understand what makes a good sentence, it's important to understand one principle:

a sentence, at its very basic level, is about actors and actions. As such, the subject of a

sentence should point clearly to the actor, and the verb of the sentence should describe

the important action.

This principle might seem so obvious to you that you don't think that it warrants further

discussion. But think again. Look at the following sentence, and then try to determine,

in a nutshell, what is wrong with it:

o

There was uncertainty in President Clinton's mind about the intention of the

Russians to disarm their nuclear weapons.

This sentence has no grammatical errors. But certainly it lumbers along, without any

force. Now consider the following sentence:

o

President Clinton remained unconvinced that the Russians intended to disarm

their nuclear weapons.

What changes does this sentence make? We can point to the more obvious changes:

omitting the "there is" phrase; replacing the wimpy "uncertainty" with the more

powerful "remained unconvinced"; replacing the abstract noun "intention" with the

stronger verb "intended." But what principle governs these many changes? Precisely the

one mentioned earlier: that the actor in a sentence should serve as the sentence's

subject, and the action should be illustrated forcefully in the sentence's verbs.

Whenever you feel that your prose is confusing or hard to follow, find the actors and the

actions of your sentences. Is the actor the subject of your sentence? Is the action a verb?

If not, rewrite your sentence accordingly.

Principle Two: Be Concrete

Student writers rely too heavily on abstract nouns: they use "expectation" when the verb

"expect" is stronger; they write "evaluation" when "evaluate" is more vivid. But why use

an abstract noun when a verb will do better? Many students believe that abstract nouns

permit them to sound more "academic." But when you write with a lot of abstract nouns,

you risk confusing your reader. You also end up putting yourself in a corner,

syntactically. Consider the following:

Nouns often require prepositions.

Too many prepositional phrases in a sentence are hard to follow. Verbs, on the other

hand, can stand on their own. They are cleaner; they don't box you in. If you need some

proof for this claim, consider the following sentence: An evaluation of the tutors by the

administrative staff is necessary in servicing our clients. Notice all of the prepositional

phrases that these nouns require. Now look at this sentence, which uses verbs: The

administrative staff evaluates the tutors so that we can better serve our clients. This

sentence is much easier to read.

Abstract nouns often invite the "there is" construction.

Consider this sentence: There is much discussion in the department about the

upcoming tenure decision. We might rewrite this sentence as follows: The faculty

discussed who might earn tenure. The result, again, is a sentence that is more direct

and easier to read.

Abstract nouns are, well, abstract.

Using too many abstract nouns will leave your prose seeming un-rooted. Instead, use

concrete nouns as well as strong verbs to convey your ideas.

Abstract nouns can obscure your logic.

Note how hard it is to follow the line of reasoning in the following sentence. (I've boldfaced the nouns that might be rewritten as verbs, or as adjectives.) Decisions with

regard to the dismissal of tutors on the basis of their inability to detect grammar

errors in the papers of students rest with the Director of Composition. Now consider

this sentence. When a tutor fails to detect grammar errors in student papers, the

Director of Composition must decide whether or not to dismiss her.

Which sentence, in your opinion, is easier to follow?

(PS. You should note that abstract nouns often force you to use clumsy phrases like "on

the basis of" or "in regard to." How much better the above sentence is when it relies on

the simple word "when" to make its logical connection.)

Principle Two, The Exception: Abstract Nouns & When To Use Them.

Of course writers will find instances where the abstract noun is essential to the sentence.

Sometimes, abstract nouns make references to a previous sentence ("these arguments,"

"this decision," etc.). In other instances, they allow you to be more concise ("her needs"

vs. "what she needed"). In still other instances, the abstract noun is a concept important

to your argument: freedom, love, revolution, and so on. Still, if you examine your prose,

you will probably find that you overuse abstract nouns. Omitting from your writing

those abstract nouns that aren't really necessary makes for leaner, "fitter" prose.

Principle Three: Be Concise

One of the most exasperating things about reading student texts is that students don't

know how to write concisely. Students use phrases when a single word will do. Or they

offer pairs of adjectives and verbs where one is enough. Or they over-write, saying the

same thing two or three times with the hope that, one of these times, they'll get it the

way they want it.

Stop the madness! It's easy to delete words and phrases from your prose once you've

learned to be ruthless about it.

Do you really need words like "actually," "basically," "generally," and so on? If you don't

need them, why are they there? Are you using two words where one will do? Isn't "first

and foremost" redundant? What is the point of "future" in "future plans?" And why do

you keep saying, "In my opinion?" Doesn't the reader understand that this is your

paper, based on your point of view?

Sometimes you won't be able to fix a wordy sentence by simply deleting a few words or

phrases. You'll have to rewrite the whole sentence. For example: Plagiarism is a serious

academic offense resulting in punishments that might include suspension or dismissal,

profoundly affecting your academic career. The idea here is simple: Plagiarism is a

serious offense with serious consequences. Why not say so, simply?

Principle Four: Be Coherent

At this point in discussing style, we move from the sentence as a discrete unit to the way

that sentences fit together. Coherence (or the lack of it) is a common problem in student

papers. Sometimes a professor encounters a paper in which all the ideas seem to be

there, but they are hard to follow. The prose seems jumbled. The line of reasoning is

anything but linear. Couldn't the student have made this paper a bit more, well,

readable?

While coherence is a complicated and difficult matter to address, we do have a couple of

tricks for you that will help your sentences to "flow." Silly as it sounds, you should

"dress" your sentences the way a bride might - wearing, as the saying goes, something

old and something new. In other words, each sentence you write should begin with the

old - that is, with something that looks back to the previous sentence. Then your

sentence should move on to telling the reader something new. If you do this, your line of

reasoning will be easier for your reader to follow.

While this advice sounds simple enough, it is in fact not always easy to follow. Let's take

the practice apart, so that we can better understand how our sentences might be "welldressed."

Consider, first, the beginning of your sentences. The coherence of your paper depends

largely upon how well you begin your sentences. "Well begun is half done" - so says

Mary Poppins, and in this case (as in all cases, really) she is right.

Beginning a sentence is hard work. When you begin a sentence, you have three

important matters to consider:

Is your topic also the subject of your sentence?

Usually, when a paper lacks coherence, it is because the writer has not been careful to

ensure that the TOPIC of his sentence is also the grammatical SUBJECT of his sentence.

If, for instance, I am writing a sentence whose topic is Hitler's skill as a speaker, then the

grammatical subject of my sentence should reflect this: Hitler's skill as a speaker was

far more crucial to the rise of the Nazi party than was his skill as a politician. If, on the

other hand, I bury my topic in a subordinate clause, look what happens: Hitler's rise to

power, an event which came about because of Hitler's skill as a speaker, was not due to

any real political skill. Note how, in this sentence, the real topic is obscured.

Are the topics/subjects of your sentences consistent?

For a paragraph to be coherent, most of the sentence subjects should be the same. To

check for consistency, pick out a paragraph and make a list of its sentence subjects. See

if any of the subjects seem out of place. For example, if you are writing a paragraph

about the sex lives of whales, do most of your sentence subjects reflect that topic? Or do

some of your sentences have as their subjects researchers? Sea World? Jacques

Cousteau? While Sea World may indeed have a place in your paper, you will confuse

your reader if a paragraph's sentence subjects point to too many competing ideas.

Revise your sentences (perhaps your entire paragraph) for coherence.

Have you marked, when appropriate, the transitions between ideas?

Coherence depends upon how well you connect a sentence to the one that came before.

You will want to make solid transitions between your sentences, using words such as,

however or therefore. You will also want to signal to your reader whenever, for example,

something important or disappointing comes up. In these cases, you will want to use

expressions like it is important to note that, unfortunately, etc. You might also want to

indicate time or place in your argument. If so, you will use transitions such as, then,

later, earlier, in my previous paragraph, etc.

Be careful not to overuse transition phrases. Some writers think transition phrases can,

all by themselves, direct a reader through an argument. Indeed, sometimes all a

paragraph needs is a "however" in order for its argument suddenly to make sense. More

often, though, the problem with coherence does not stem from a lack of transition

phrases, but from the fact that the writer has not articulated, for himself, the

connections between his ideas. Don't rely on transition phrases alone to bring sense to

muddled prose.

Principle Five: Be Emphatic

We have been talking about sentences and their beginnings. But what about sentences

and how they end?

If the beginnings of your sentences must look over their shoulders at what came before,

the ends of your sentences must forge ahead into new ground. It is the ends of your

sentences, then, that must be courageous and emphatic. You must construct your

sentences so that the ends pack the punch.

To write emphatically, follow these principles:

As we've said, declare your important ideas at the end of your sentence.

Shift your less important ideas to the front.

Trim the ends of your sentences.

Don't trail off into nonsense, don't repeat yourself, don't qualify what you've just said if

you don't have to. Simply make your point and move on.

Use subordinate clauses to house subordinate ideas.

Put all the important ideas in main clauses, and the less important ideas in subordinate

clauses. If you have two ideas of equal importance that you want to express in the same

sentence, use parallel constructions or semi-colons. These two tricks of the trade are

perhaps more useful than any others in suggesting a balanced significance between

ideas.

Principle Six: Be In Control

Readers know when a writer has lost control of his sentences when these sentences run

on and on. Take control of your sentences. When you read over your paper, look for

sentences that never seem to end. Your first impulse might be to take these long

sentences and divide them into two (or three, or four). This simple solution often works.

But sometimes this strategy isn't the most desirable one: it might lead to short, choppy

sentences. Moreover, if you always cut your sentences in two, you'll never learn how it is

that a sentence might be long and complex without violating the boundaries of good

prose.

So what do you do when you encounter an overly long sentence? First consider the point

of your sentence: usually it will have more than one point, and sorting out the points

helps to sort out the grammar. Consider carefully the points that you are trying to make

and the connections between those points. Then try to determine which grammatical

structure best serves your purpose.

Are the points of equal importance?

Use a coordinating conjunction or a semi-colon to join the ideas together. Try to use

parallel constructions when appropriate.

Are the points of unequal importance?

Use subordinate clauses or relative clauses to join the ideas.

Does one point make for an interesting aside?

Insert that point between commas, dashes, or even parentheses at the appropriate

juncture in the sentence.

Do these ideas belong in the same sentence?

If not, create two sentences.

Fixing your Essay’s Formal Language

Go through your essay and search for:

□ Numbers

□ Contractions

□ Slang

□ Informal or unsophisticated words

□ Personal phrases such as I, you, we

Circle them and put in alternative words/phrases

Get a second

to:

Go through your essay and search for:

□ Numbers

□ Contractions

□ Slang

□ Informal or unsophisticated words

□ Personal phrases such as I, you, we

Circle them and put in alternative words/phrases

Fixing your Essay’s Grammar

1. Check your sentence structure

□

Vague pronoun reference

□

Wrong/missing inflected ends

□

Wrong/missing preposition

□

Tense shift

□

Unnecessary shift in person

□

Sentence fragment

□

Wrong tense or verb form

□

Subject-verb agreement

□

Pronoun agreement error

□

Run-on

□

Fused sentences

□

Misplaced modifier

□

Dangling modifiers

□

Wrong word

2. Check your punctuation

□

Missing comma after introductory phrases

□

Missing comma in compound sentence

□

No comma in nonrestrictive relative clauses

□

Comma splice

□

Possessive apostrophe error

□

Missing comma in a series

□

Unnecessary commas with restrictive clauses

□

Its/it's error

Fixing your Essay’s Style

The Basic Principles of the Sentence:

□ Principle One: Focus on Actors and Actions

□ Principle Two: Be Concrete

□ Principle Three: Be Concise

□ Principle Four: Be Coherent

□ Principle Five: Be Emphatic

□ Principle Six: Be In Control

Fixing your Essay’s Structure

1. Make a paragraph here! Record the last sentence of your introduction, the first

sentence of each of your body paragraphs, and ending with the first sentence of your

conclusion.

?? Ask yourself: ??

□ Does your paragraph contain 5 sentences?

□ Does this paragraph make sense? (it most definitely won’t be the most interesting or

reader-pleasing paragraph, but it should make sense)

□ Does everything relate?

Does your paragraph contain:

□ Your thesis?

□ 3 topic sentences (one from the beginning of each body paragraph)?

□ Your restated thesis?

Basic Essay Structure

Introduction

Body

Para. 1

Starts generally, with info about the

topic

Defines terms

Narrows

Ends with a thesis statement

Begins with a topic sentence that outlines the 1st point from your thesis

Proof

Evidence

Facts

Deal with opposition

Body

Para. 2

Begins with a topic sentence that outlines the 2nd point from your thesis

Proof

Evidence

Facts

Deal with opposition

Body

Para. 3

Begins with a topic sentence that outlines the 3rd point from your thesis

Proof

Evidence

Facts

Deal with opposition

Conclusion

Begins with restated thesis

Reviews argument & deals with

opposition

Pushes readers to wonder, ask

questions, think globally