* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download TRUSTEES FOR ALASKA

Survey

Document related concepts

Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project wikipedia , lookup

Biodiversity action plan wikipedia , lookup

Mission blue butterfly habitat conservation wikipedia , lookup

Marine conservation wikipedia , lookup

Habitat conservation wikipedia , lookup

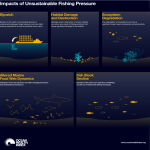

Overexploitation wikipedia , lookup

Transcript