* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Premature Infant: Nursing

Maternal physiological changes in pregnancy wikipedia , lookup

Maternal health wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Fetal origins hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Infant mortality wikipedia , lookup

Long-term care wikipedia , lookup

Infection control wikipedia , lookup

Preventive healthcare wikipedia , lookup

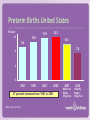

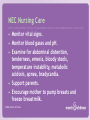

The Premature Infant: Nursing Assessment and Management, 2nd Edition Lyn E. Vargo, PhD, NNP, RNC Carol Wiltgen Trotter, PhD, NNP, RNC Slides prepared by Margaret Comerford Freda, EdD, RN, CHES, FAAN Preterm Births United States Percent 12.3 11.9 12 10.8 10.1 9.4 7.6 8 4 0 1981 1991 2001 2003 27 percent increase from 1981 to 2001 © 2006, March of Dimes 2007 March of Dimes Objective 2010 Healthy People Objective Transition to Extrauterine Life • Requires many physiologic changes for the infant • Nurses need to understand general principles of delivery-room management, resuscitation and thermoregulation for premature infants. © 2006, March of Dimes Delivery-Room Management Certification by the Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) of the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) is essential for all nurses who work with premature infants. © 2006, March of Dimes Delivery-Room Management Risks • • • • • • • Tendency to have difficulty with transition Vulnerable to cold stress More lung immaturity and RDS More intracranial hemorrhage More hypoglycemia Potential for oxygen-related injuries High risk of developing NEC © 2006, March of Dimes Delivery-Room Management Precautions • Follow resuscitation from NRP guidelines. • Avoid rough handling during resuscitation. • Reduce heat loss even if resuscitation is not required. • Preterm infants may require endotracheal intubation and surfactant administration soon after birth. © 2006, March of Dimes Delivery-Room Management Precautions (Continued) • Administer medication slowly as recommended by NRP guidelines. • Follow glucose levels carefully. Glycogen stores may be decreased. Infant may experience hypoglycemia secondary to perinatal compromise. • Maintain normal oxygen range after resuscitation. © 2006, March of Dimes Major Physiologic Problems of the Premature Infant • RDS, BPD, apnea of prematurity and • • • • chronic lung disease PDA and hypotension ROP Immune-system immaturity that increases the risk of infection P-IVH © 2006, March of Dimes Additional Physiologic Problems of the Premature Infant • • • • • • • • Skin immaturity and fragility Thermoregulation GI issues Fluid and electrolyte imbalances related to immature renal function Acid-base disorders Pain management Developmental issues related to the CNS Impact of the NICU environment © 2006, March of Dimes RDS • Incidence 10% for all premature infants • Incidence 50% for 26 week to 28 weeks • Risk factors: – Low gestational age – Male – Born to diabetic mothers – Born after an asphyxial insult before birth – Born after maternal-fetal hemorrhage – Multiple gestation © 2006, March of Dimes RDS (Continued) Complex respiratory disease characterized by diffuse alveolar atelectasis of the lungs, primarily caused by a deficiency of surfactant. This leads to higher surface tension at the surface of alveoli, which interferes with normal exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide. © 2006, March of Dimes NIH Recommendations for Use of Antenatal Steroids • Give to all pregnant women 24 to 34 weeks gestation who are at risk for preterm delivery within 7 days: – 2 doses of 12 mg of betamethasone IM 24 hours apart OR – 4 doses of 6 mg of dexamethasone IM 12 hours apart • Repeat courses of corticosteroids should not be given routinely in pregnant women. © 2006, March of Dimes Chain of Events with Surfactant Delivery © 2006, March of Dimes Signs and Symptoms of RDS • Difficulty in establishing normal respiration, especially if infant has risk factors for RDS • Expiratory grunting while the infant is not crying • Intercostal and sternal retractions due to increased rib cage compliance and decreased lung compliance © 2006, March of Dimes Signs and Symptoms of RDS (Continued) • Nasal flaring • Cyanosis • Tachypnea © 2006, March of Dimes RDS Treatment • Thermoregulation • Fluid balance and nutrition • Skin care • Pain assessment • Developmental care • Family care © 2006, March of Dimes RDS Treatment (Continued) • Focus is to prevent and minimize atelectasis. • Minimize untoward effects of oxygen and barotrauma or volutrauma. • Treat underlying cardiovascular infectious and other physiologic problems. • Maintain a balanced physiologic environment. © 2006, March of Dimes Surfactant Therapy • Surfactant coats the inside of the alveoli. It prevents collapse (atelectasis) and keeps alveoli open at the end of expiration. • It is given via endotracheal tube. • Prophylactic therapy appears more beneficial than rescue therapy. © 2006, March of Dimes Surfactant Therapy (Continued) • Criteria for identifying at-risk infants who would benefit from prophylactic treatment are unclear. • Multiple doses lead to improved clinical outcomes. © 2006, March of Dimes Adjunct Treatments for RDS CPAP – A method of assisting lung expansion with continuous distending pressure – A valuable adjunct when spontaneous breathing is adequate and pulmonary disease is not excessive – Increases transpulmonary pressure; improves oxygenation and ventilation – Reduces tachypnea and grunting © 2006, March of Dimes Adjunct Treatments for RDS (Continued) • HFV – Allows the use of small tidal volumes (smaller than anatomic dead space) and high frequencies. – Rates of 150 to 3,000 breaths per minute can be used depending on the type of HFV. – HFV limits large tidal volumes and wide ventilator pressure swings associated with volutrauma/ barotrauma caused by traditional mechanical ventilation. • Oscillation © 2006, March of Dimes RDS Nursing Care Any nurse caring for an infant with RDS must: – Be familiar with RDS pathophysiology – Recognize symptoms of RDS – Initiate interventions as indicated © 2006, March of Dimes RDS Nursing Care (Continued) • Maintain paO2 and oxygen saturation levels. • Recognize importance of weaning oxygen and other ventilator parameters. • Recognize complications arising from RDS, intubation and mechanical ventilation. • Utilize proper endotracheal suctioning techniques. © 2006, March of Dimes RDS Nursing Care (Continued) • Provide mouth and skin care. • Maintain proper positioning. • Provide adequate fluid and electrolyte balance. • Monitor blood glucose levels. • Reduce environmental stressors. • Provide parental support. © 2006, March of Dimes BPD • A significant problem for premature • • • • infants Uncommon after 32 weeks gestation A secondary disease that develops in neonates treated with positive pressure ventilation and oxygen for primary lung problems such as RDS 7,500 new cases every year in the United States 10% die by 1 year of age © 2006, March of Dimes Signs and Symptoms of BPD • Hypoxemia with prolonged oxygen • • • • requirement Hypercapnia, tachypnea with increased work of breathing Episodic bronchospasm with wheezing In severe cases, CHF with cor pulmonale Abnormal postures of neck and upper trunk © 2006, March of Dimes Cascade of Events Occurring in BPD © 2006, March of Dimes BPD Treatment • Therapy is preventive and supportive. • Preventive measures begin prenatally with preventing prematurity and using a single course of antenatal steroids. • Includes early, careful management of RDS, use of low ventilator pressures, and careful use of oxygen and exogenous surfactant treatment. © 2006, March of Dimes AAP/CPS Summary/Recommendations on Postnatal Steroids • Systemic administration of dexamethasone to mechanically ventilated premature infants decreases incidence of chronic lung disease and extubation failure. Does not decrease overall mortality. • Dexamethasone treatment for VLBW infants is associated with complications (impaired growth and neurodevelopmental delay). © 2006, March of Dimes AAP/CPS Summary/Recommendations on Postnatal Steroids (Continued) • Use of inhaled corticosteroids to prevent CLD has not shown benefits. • Routine use of dexamethasone for the prevention of BPD in VLBW infants is not recommended. • Postnatal use of systemic dexamethasone for the prevention of BPD should be limited to carefully designed randomized doublemasked controlled trials. © 2006, March of Dimes AAP/CPS Summary/Recommendations on Postnatal Steroids (Continued) Outside the context of a randomized controlled trial, the use of postnatal corticosteroids should be limited to exceptional clinical circumstances (an infant on maximal ventilatory support). Parents should be fully informed about the shortand long-term risks and agree to treatment. © 2006, March of Dimes BPD Nursing Care • Prevent further lung damage. • Wean ventilator and oxygen support slowly. • Recognize that stressful situations can minimize hypoxemia-inducing events. • Use sucrose with nonnutritive sucking before painful procedures to decrease pain. © 2006, March of Dimes BPD Nursing Care (Continued) • Preoxygenation (increasing FiO2 just before suctioning) may help prevent hypoxemia with suctioning. • A consistent caregiver is helpful to parents. • Use fortified breastmilk or premature specialty formula for a consistent weight gain of 10 g to 30 g per day. • Kangaroo care promotes bonding. © 2006, March of Dimes Kangaroo Care • Improvement in gas exchange and temperature in premature infants • No adverse affect on physiologic stability • Improvement in lactation outcomes in mothers wishing to breastfeed premature infants • Positive impact on the parenting process © 2006, March of Dimes Apnea of Prematurity • 50% of NICU infants • Periods of cessation of respiration for longer than 10 seconds to 15 seconds • Apneic episodes frequently accompanied by cyanosis, bradycardia, pallor or hypotonia • Exact cause unknown but thought to be due to immature CNS © 2006, March of Dimes Types of Apnea in Premature Infants • Central: Absent breathing movements/ effort • Obstructive: Breathing movements but no air flow • Mixed: Mixture of obstructive and central apnea © 2006, March of Dimes Apnea Treatment • Cardiac and respiratory monitoring until no apnea episodes for 5 to 7 days • Neutral thermal environment • Careful positioning; avoid flexion and hyperextension of the neck © 2006, March of Dimes Apnea Treatment (Continued) • Attention to gastric tube placement and infusion rate during tube feeding • Nasal CPAP • Methyxanthines (oral to intravenous aminophylline, theophylline and caffeine) © 2006, March of Dimes Apnea Nursing Care • Assess infant’s color, perfusion, respiratory rate, heart rate, position and oxygen saturation. • Document frequency and severity of episodes and type and amount of stimulation required to interrupt the event. • Ensure bag and mask set-ups with oxygen available at infant bedside. © 2006, March of Dimes PDA • The most common cardiac complication in premature infants • Incidence inversely related to gestational age • Occurs in 45% of infants with a birthweight <1,750 g • Occurs in 80% of infants with a birthweight <1,200 g © 2006, March of Dimes Signs and Symptoms of PDA • Signs and symptoms of congestive heart failure, increased need for oxygen and inability to wean from ventilator • Widened pulse pressure, an active precordium, bounding peripheral pulses and tachycardia with or without a gallop • Echocardiogram most useful to evaluate PDA © 2006, March of Dimes Left-to-Right Shunt Through PDA © 2006, March of Dimes PDA Treatment • Treatment is controversial. • Medical management with fluid restriction and diuretics may be the initial approach. • Indomethacin has been effective in closing PDAs (dosage depends on weight, gestation and renal function). © 2006, March of Dimes PDA Nursing Care • Continually assess high-risk infants for pulse, heart rate, pulse pressure, perfusion, and auscultation for the presence of a murmur. • Know dosage and contraindications for indomethacin. • Assess infant after indomethacin for ductal closure, decreased urine output and thrombocytopenia. • Teach and reassure parents. © 2006, March of Dimes ROP • A significant cause of blindness in children initiated by delay in retinal vascular growth • The more premature the infant, the more likely the infant is to have ROP. • 82% of infants weighing <1,000 g at birth develop ROP. © 2006, March of Dimes ROP (Continued) • 47% of infants weighing 1,000 g to 1,500 g at birth develop ROP. • Other risk factors: prolonged mechanical ventilation and oxygen administration, hyperoxia, hypoxia, sepsis, acidosis, shock © 2006, March of Dimes Long-Term Consequences of ROP • Myopia (nearsightedness) • Strabismus (crossed eye) • Amblyopia (lazy eye) • Astigmatism • Glaucoma • Late retinal detachment • Blindness © 2006, March of Dimes AAP: Screening Premature Infants for ROP • First exam occurs 4 to 6 weeks after birth or 31 to 33 weeks postconceptional age. • Two exams after pupillary dilation using indirect ophthalmoscopy if: – Weight at birth <1,500 g or gestational age <28 weeks – High-risk event and weight at birth 1,501 g to 2000 g or gestational age 29 to 36 weeks © 2006, March of Dimes ROP Treatment • ROP progresses at different rates in different infants. • The goal of treatment for ROP is prevention of blindness. • Surgical therapies—Laser photocoagulation and cryotherapy © 2006, March of Dimes Characteristics of Neonatal Sepsis Early Onset <7 days Late Onset 7 days to 3 months Late, Late Onset >3 months Intrapartum complications Often present Usually absent Varies Transmission Vertical; organisms often acquired from mother’s genital tract Vertical or via postnatal environment Usually postnatal environment Clinical manifestations Fulminant course, multisystem involvement, pneumonia Insidious, focal infection, meningitis common Insidious Case-fatality rate 5 percent to 20 percent 5 percent Low M.S. Edwards, 2002a. Reprinted with permission. © 2006, March of Dimes Deficiencies in Neonatal Host Defenses that Predispose to Infection • Anatomic barriers—Injuries during delivery (skin abrasions) • Invasive procedures in the nursery (umbilical artery catheters, endotracheal tubes) © 2006, March of Dimes Deficiencies in Neonatal Host Defenses that Predispose to Infection, Continued Phagocytic cells – Small PMN leukocyte storage pool – Decreased PMN leukocyte adherence – Decreased PMN leukocyte and monocyte chemotaxis – Decreased phagocytosis in stressed neonates – Decreased PMN leukocyte intracellular killing in stressed neonates © 2006, March of Dimes Deficiencies in Neonatal Host Defenses that Predispose to Infection, Continued • Complement – Decreased levels of complement – Decreased expression of complement receptors • Cellular immunity – Possible defects in T-cell immunoregulation © 2006, March of Dimes Deficiencies in Neonatal Host Defenses that Predispose to Infection, Continued Humoral immunity – – – – – Decreased IgA, IgM Decreased IgG in premature neonates Impaired antibody function Decreased levels of fibronectin Decreased levels of cytokine (interferon, tumor necrosis factor) © 2006, March of Dimes Meningitis • Severely debilitating illness in VLBW infants • Caused by the same pathogens that cause sepsis • Incidence of culture-proven meningitis: 1.8% • Occurs in neonates with lower mean birthweights and gestational ages • Residual major neurologic abnormalities and subnormal scores on MDI on the Bayley Scales of Infant Development © 2006, March of Dimes Meningitis (Continued) • Most common etiology is hematogenous spread from the bloodstream to the meninges. • Can be early- or late-onset • Mortality is usually higher with early onset disease. © 2006, March of Dimes Signs and Symptoms of Meningitis • Lethargy • Hypotonia • Temperature instability • Increased oxygen requirements • Apnea • Bradycardia • Feeding intolerance • Seizures © 2006, March of Dimes Pneumatocele © 2006, March of Dimes Pneumonia in a Premature Infant © 2006, March of Dimes Pneumonia • Developed: – In utero through transplacental transfer of organisms and aspiration of pathogens from amniotic fluid of mothers with chorioamnionitis – During/After delivery through aspiration of infected materials – Postdelivery through inhalation of particles from individuals or equipment; through contaminated endotracheal tubes; through hematogenous spread from pathogens in the bloodstream • Most common cause is GBS. © 2006, March of Dimes Signs and Symptoms of Pneumonia Early signs are the same as for sepsis: • Lethargy or irritability • Poor feeding • Temperature instability • Poor color • Respiratory signs--tachypnea, apnea, cyanosis, retractions, grunting, nasal flaring and retractions © 2006, March of Dimes Treatment of Sepsis, Meningitis and Pneumonia • Early identification of neonate at risk is essential for prevention of morbidity and mortality. • Develop a culture of prevention of infection in NICU. • Eradicate the pathogen with medications. • Minimize sequelae. © 2006, March of Dimes Nursing Care of Sepsis, Meningitis and Pneumonia • Monitor respiratory status, oxygen support, mechanical ventilation. • Watch for worsening apnea/bradycardia. • Suctioning PRN • Volume replacements PRN with isotonic solutions © 2006, March of Dimes Nursing Care of Sepsis, Meningitis and Pneumonia, Continued • Blood products PRN • Minimal handling to avoid extra stress • Watch for seizures. © 2006, March of Dimes NEC • The most common neonatal intestinal emergency • Characterized by intestinal ischemia, most often involving the terminal ileum • Pathogenesis is uncertain. • Three major factors: bowel wall ischemia; bacterial invasion of the bowel wall; enteral feedings © 2006, March of Dimes Pathogenesis of NEC © 2006, March of Dimes Three Stages of NEC 1. Generalized symptoms of early sepsis, including temperature instability, lethargy, apnea and bradycardia, feeding intolerance, abdominal distention, and stools that test positive for occult blood 2. Severe abdominal distention and tenderness, visible bowel loops, grossly bloody stools, metabolic acidosis, poor perfusion and a mottled skin color 3. Fulminant signs of SIRS, including shock, mixed acidosis, DIC and neutropenia © 2006, March of Dimes NEC Treatment • Goals: – Stabilize the neonate. – Treat the infection. – Rest the intestinal tract. • Discontinue feedings. • Initiate IV access for fluids and antibiotics. • NG tube to decompress GI tract © 2006, March of Dimes NEC Nursing Care • Monitor vital signs. • Monitor blood gases and pH. • Examine for abdominal distention, tenderness, emesis, bloody stools, temperature instability, metabolic acidosis, apnea, bradycardia. • Support parents. • Encourage mother to pump breasts and freeze breastmilk. © 2006, March of Dimes Intrapartum Antibiotic Prophylaxis to Prevent Perinatal GBS Vaginal and rectal GBS screening cultures at 35 to 37 weeks gestation for all pregnant women (unless patient had GBS bacteriuria during the current pregnancy or a previous infant with invasive GBS disease). Intrapartum prophylaxis indicated Intrapartum prophylaxis not indicated • Previous infant with invasive GBS disease • GBS bacteriuria during current pregnancy • Positive GBS screening culture during current pregnancy (unless a planned cesarean delivery, in the absence of labor or amniotic membrane rupture, is performed) • Unknown GBS status (culture not done, incomplete or results unknown) and any of the following: • Previous pregnancy with positive GBS screening culture (unless a culture was also positive during the current pregnancy) • Planned cesarean delivery performed in the absence of labor or membrane rupture (regardless of maternal GBS culture status) • Negative vaginal and rectal GBS screening culture in late gestation during the current pregnancy, regardless of intrapartum risk factors – Delivery at <37 weeks gestation – Amniotic membrane rupture ≥18 hours – Intrapartum temperature ≥100.4°F (≥38.0°C)† © 2006, March of Dimes GBS Prophylaxis for Women with Threatened Preterm Delivery © 2006, March of Dimes Prevention of Early-Onset GBS Disease in the Newborn © 2006, March of Dimes PBPs for Prevention of Nosocomial Infections in NICUs • Increased compliance with hand-hygiene standards • Improved accuracy of the diagnosis of bacteremia • Reduced line and line connection (hub) bacterial contamination © 2006, March of Dimes PBPs for Prevention of Nosocomial Infections in NICUs (Continued) • Maximal barrier precautions for central line placement • Decreased – Number of skin punctures – Duration of IV lipid infusion – Duration of central venous line use © 2006, March of Dimes IVH/PVH • 50% will die. • Occurs in 25% to 30% of all VLBW infants discharged from Level III NICUs • Associated primarily with prematurity • Infants <28 weeks gestation are at greatest risk. © 2006, March of Dimes IVH/PVH (Continued) • Small (Grades I and II) – Grade I hemorrhage is an isolated germinal matrix hemorrhage. – Grade Il is an IVH with normal ventricular size. • Moderate (Grade III) is an IVH with acute ventricular dilation. • Severe (Grade IV) is an IVH with parenchymal hemorrhage. © 2006, March of Dimes Venous Drainage of Cerebral White Matter © 2006, March of Dimes Signs and Symptoms of IVH/PVH • Can be subtle; sometimes only decreased hematocrit or hemoglobin levels • May evolve over several hours and include decreased activity, hypotonia, altered consciousness, respiratory disturbances • Can develop rapidly, with seizures, decerebrate posturing, fixed pupils © 2006, March of Dimes IVH/PVH Treatment and Nursing Care • Optimal treatment is prevention. • Minimize brain tissue destruction. • Minimize pain and stress. • Minimize crying, suctioning, rapid bolus infusions. © 2006, March of Dimes IVH/PVH Treatment and Nursing Care (Continued) • Maintain neutral thermal environment. • Elevate head 30º. • Use sucrose pacifiers, topical anesthetics for procedures. • Provide parental support. © 2006, March of Dimes PBPs for Prevention of IVH and PVL • Administer antenatal steroids. • Optimize peripartum management. • Administer antenatal antibiotics for preterm rupture of the membranes. • Delivery-room resuscitation by neonatologists and an experienced team © 2006, March of Dimes PBPs for Prevention of IVH and PVL (Continued) • Maintain the baby’s temperature >36° centigrade. • Maintain cardiorespiratory stability while administering surfactant. • Optimize direct clinical management by neonatologists. • Implement measures to minimize pain and stress responses. © 2006, March of Dimes PBPs for Prevention of IVH and PVL (Continued) • Use developmental care. • Judiciously use narcotic sedation (low dose, continuous). • Avoid early lumbar puncture (72 hours old). • Use optimal positioning. © 2006, March of Dimes PBPs for Prevention of IVH and PVL (Continued) • In terms of fluid volume treatment of hypotension, there is no evidence demonstrating benefit of using MAP 30 rather than MAP > estimated gestational age weeks. • Use postnatal indomethacin judiciously. • Optimize respiratory management. • Use postnatal dexamethasone judiciously. © 2006, March of Dimes Goals of Nursing Care to Promote Parental Attachment • Opening the intensive care nursery to parents • Transporting the mother to be near her infant • Maternal day care for premature infants • Rooming in for parents • Individualized nursing care plans • Early discharge © 2006, March of Dimes Goals of Nursing Care to Promote Parental Attachment (Continued) • Listening to parents during the infant’s hospitalization and after discharge • Parent support groups • Programmed contact and reciprocal interaction • Transporting the healthy premature infant to the mother © 2006, March of Dimes Goals of Nursing Care to Promote Parental Attachment (Continued) • Home-based interventions for young parents • Discussion with parents after discharge • Kangaroo care • Nurse home visitation © 2006, March of Dimes March of Dimes Prematurity Campaign Multi-year, multimillion-dollar campaign to help families have healthier babies by: • Funding research to find causes of premature birth • Educating women about risk reduction • Providing support to families © 2006, March of Dimes March of Dimes Prematurity Campaign (Continued) • Expanding access to health care coverage for prenatal care • Helping providers learn ways to help reduce risk of early delivery • Advocating for access to insurance to improve maternity care and infant health outcomes © 2006, March of Dimes March of Dimes NICU Family Supportsm • Provides emotional and informational resources to families with a newborn in the NICU • In more than 50 NICUs in the United States by 2007 • marchofdimes.com/prematurity/nicu © 2006, March of Dimes March of Dimes Share Your Story • Online community for families with a child in the NICU • Users share NICU experiences, participate in online discussions and meet other NICU families. • More than 10,000 registered members • marchofdimes.com/share © 2006, March of Dimes