* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Electroconvulsive therapy during pregnancy: a systematic review of case studies REVIEW ARTICLE

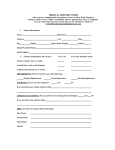

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript