* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Thinkwell`s Microeconomics

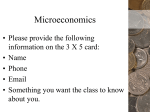

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript