* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Canine Anterior Uveitis

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

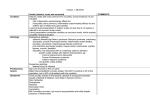

CE Article 3 CE CREDITS Canine Anterior Uveitis Brett Wasik, DVM, DACVIM-SAIM VCA Animal Diagnostic Clinic Dallas, Texas Elizabeth Adkins, DVM, MS, DACVOa Hope Center for Advanced Veterinary Medicine Vienna, Virginia Abstract: Canine anterior uveitis can be a debilitating, painful, vision-threatening disease. Several local and systemic diseases can cause anterior uveitis. Because the eye is limited in its ability to respond to injury, different diseases produce similar clinical signs, making an etiologic diagnosis difficult but imperative to improve the likelihood of a successful outcome. A thorough history and complete ocular and physical evaluations are necessary to ensure timely and accurate diagnosis. This article reviews the pathophysiology, most common causes, diagnostic recommendations, current therapeutic options, potential complications, and prognosis for canine anterior uveitis. A nterior uveitis is a painful, inflammatory disorder endothelium of the iridal blood vessels. Tight junctions jointhat is one of the most frequently observed ocular ing these cells maintain the continuity of the barrier. When diseases in dogs.1 Intrinsic ocular abnormalities and the BAB is breached as a result of uveal inflammation, promultiple systemic diseases can trigger its development.2 tein and blood cells leak into the fluid medium of the eye, Establishing the etiology is essential because inappropriate resulting in aqueous flare. therapy may result in loss of vision. Appropriate therapy can be curative but sometimes is, at best, long term and pallia- Pathophysiology of Ocular Inflammation Anterior uveitis develops as a result of injury to the antetive. Complications are common. rior uveal tract. Pathophysiologic mechanisms responsible Anatomy of the Uveal Tract for this tissue injury include damage by organisms or neoThe uvea is the highly vascular middle layer of the eye, plastic cells spread through the bloodstream from distant located immediately beneath the sclera. It comprises the iris, anatomic sites or directly to the eyes from adjacent tissues ciliary body, and choroid. The iris and ciliary body make (e.g., meninges, optic nerve, upper respiratory tract), tisup the anterior uveal tract, and the choroid composes the sue damage from exposure to environmental or microbial posterior uveal tract. Uveitis is any inflammatory condition FIGURE 1 involving all or a portion of these tracts. Iritis and cyclitis refer to inflammation of the iris and ciliary body, respectively. Anterior uveitis, or iridocyclitis, is present when both the iris and ciliary body are inflamed. Posterior uveitis denotes inflammation of the ciliary body and choroid. Further classification is based on duration (acute, chronic, recurrent), pathology (e.g., granulomatous, suppurative), and cause (e.g., traumatic, infectious, neoplastic, immune-mediated).3 The blood–aqueous barrier (BAB) plays an important anatomic role in the development of anterior uveitis. Normally, this selectively permeable barrier prevents the influx of blood and proteins into the aqueous humor. It is formed by the nonpigmented epithelium of the ciliary body and the Multifocal iridal hemorrhages and miosis in the right a Dr. Adkins discloses that she has served as a consultant for Covance Inc. eye of a young, mixed-breed dog with immune-mediated hemolytic anemia. Flash artifact present. Vetlearn.com | November 2010 | Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® E1 ©Copyright 2010 MediMedia Animal Health. This document is for internal purposes only. Reprinting or posting on an external website without written permission from MMAH is a violation of copyright laws. FREE CE Canine Anterior Uveitis table 1 Condition Differential Diagnosis of Canine Anterior Uveitis Ocular Redness Miosis/Mydriasis Pain Discharge Uveitis Intense ciliary flush just posterior to the limbus Miosis of affected eye Glaucoma Diffuse congestion of large, deep episcleral vessels; some congestion of superficial conjunctival vessels Mydriasis of affected eye Present in Thin to no affected discharge eye Ulcerative keratitis Similar to pattern described for uveitis Normal pupil if simple; miosis if severe and secondary uveitis is present; mydriasis if secondary glaucoma is present Aqueous Flare Fluorescein Dye Uptake Decreased Present Absent Elevated Present Absent Present in Profuse, affected thick eye discharge Normal to decreased if severe Present Can be present if keratitis is severe Normal pupil size Conjunctivitis Diffuse reddening of the conjunctiva between small superficial vessels with thickening and folding of conjunctiva; small superficial vessels move with conjunctival manipulation; vessels blanch with topical epinephrine Present in Profuse, affected thick eye discharge Normal Absent Absent Horner’s syndrome Superficial conjunctival hyperemia Miosis, ptosis, may be present enophthalmos, prolapsed third eyelid Absent Normal Absent Absent Episcleritis Hyperemia localized to inflamed area with local thickening of episclera and congestion of vessels deep to conjunctiva Normal Absent Absent Normal pupil size toxins, immune-mediated mechanisms (FIGURE 1), primary intraocular neoplasms, trauma, corneal ulceration, and cataract formation.4–6 Tissue injury and the continued presence of bacteria or viruses or their genetic material results in inflammation. This inflammation, if left unresolved, can damage delicate ocular tissues. The inflammatory mediators that can incite classic ocular changes associated with anterior uveitis (i.e., aqueous flare, photophobia, hyperemia, miosis, decreased intraocular pressure [IOP]) are the arachidonic acid metabolites—prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and leukotrienes. Arachidonic acid is released from cell membrane phospholipids through the action of phospholipase A2 after tissue injury. Cyclooxygenase converts arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and prostacyclins, whereas lipoxygenase converts arachidonic acid into leukotrienes and hydroperoxy and hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids.5 In response to the release of these metabolites from cell membrane phospholipids, inflammatory cells infiltrate the uveal tract. Platelet-activating factor (PAF) released from damaged cells, leukocytes, and mast cells results in platelet aggrega- E2 Present in Thin to no affected discharge eye Intraocular Pressure Absent Present in Excessive affected lacrimation eye tion, polymorphonuclear cell chemotaxis, increased vascular permeability, and smooth-muscle contraction with subsequent miosis.7 Histamine, prostaglandins, and kinins further increase vascular permeability.8 Prostaglandins are powerful mediators of intraocular inflammation and can cause miosis, hyperemia, and alterations in IOP.5 Inflammatory mediators (particularly prostaglandins) cause miosis by their direct effects on the iris sphincter.5,7,8 Leukocyte chemotaxis, phagocytosis, and degranulation are stimulated by complement, the clotting/fibrinolytic systems, and, most importantly, leukotrienes.8 Tissue destruction is further enhanced by release of leukocyte granules and enzymes.9 Clinical Signs Clinical signs of ocular pain (photophobia, blepharospasm, elevation of the nictitating membrane, epiphora) are frequently observed with anterior uveitis. Aqueous flare, miosis, corneal edema, conjunctival hyperemia, and scleral blood vessel congestion are also commonly documented.6 The presence of protein and cells in the aqueous humor (flare) is pathognomonic for anterior uveitis.10 Other acute Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® | November 2010 | Vetlearn.com FREE Canine Anterior Uveitis CE signs include keratic precipitates, iridal swelling, hypopyon, and hyphema.1 Chronic anterior uveitis results in accumulation of toxic wastes and inflammatory mediators within the aqueous humor. These substances damage corneal endothelial cells and disrupt the normal metabolism of the corneal stroma, leading to corneal edema.1 Inflammatory debris can accumulate in the aqueous humor drainage channels and increase IOP, predisposing the patient to glaucoma.1 Preiridal fibrovascular membrane formation also contributes to secondary glaucoma. These membranes originate as endothelial buds from anterior iridal stroma that mature into fibrous or fibrovascular membranes and can result in hyphema and glaucoma.11 They are rarely detected clinically and likely form in response to angiogenic factors released by an ischemic retina, neoplasms, or leukocytes involved in ocular inflammation.11 As the pupillary margin becomes adhesive due to chronic inflammation, anterior and posterior synechiae may form. Iris hyperpigmentation, cataracts, and deep corneal vascularization can also be consequences of chronic inflammation of the anterior uvea.1 Ocular redness, miosis, pain, and discharge can have many other causes, including glaucoma, ulcerative keratitis, conjunctivitis, Horner’s syndrome, and episcleritis. Therefore, a thorough ocular examination consisting of a Schirmer tear test (STT), fluorescein dye application, tonometry, pupillary dilation (if IOP is not elevated), slit lamp biomicroscopy, and funduscopy is necessary to distinguish between these diseases and anterior uveitis. Reductions in IOP can be an early but subtle indication of anterior uveitis.6 The decrease in IOP results from reduced production of aqueous humor due to cyclitis. Concomitantly, increases in uveoscleral aqueous humor outflow further decrease IOP. The type of vessels involved (superficial, mobile conjunctival versus deeper, immobile scleral), magnitude of increase or decrease of IOP from the normal range, presence of fluorescein dye uptake on the cornea, presence of aqueous flare, presence or absence and consistency of ocular discharge, and presence or absence of photophobia (pain) all aid in differentiating anterior uveitis from the other diseases8 (TABLE 1). Diagnostic Testing In addition to performing a complete physical and ocular examination, clinicians must obtain a detailed and thorough history.12 The client should be asked about the patient’s travel history, vaccination status, tick exposure/prophylaxis, trauma, and heartworm prophylaxis. Appropriate tests include hemography, a serum biochemistry panel, urinalysis, and serologic testing (if infectious disease is suspected) as dictated by the history, physical and ocular findings, geographic location, and travel history.12 Aqueocentesis may be considered as a final diagnostic option after exhausting other testing modalities. This is a low-yield test that is contraindicated in a sighted Box 1 Noninfectious Causes of Canine Anterior Uveitis1,6,14–16 • Lens-induced uveitis • Trauma • Idiopathic uveitis • Primary ocular neoplasia — Melanocytic tumors — Ciliary body tumors • Secondary ocular neoplasia — Lymphoma — Hemangiosarcoma — Mammary carcinoma — Oral malignant melanoma • Corneal ulceration • Pigmentary uveitis of golden retrievers • Uveodermatologic syndrome eye with active inflammation, as it may further exacerbate inflammation. Aqueous humor obtained by aqueocentesis can be used for cytologic examination, microbial culture and sensitivity testing, genetic evaluation with polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and antibody titer determination.13 Etiology Causes of anterior uveitis can be noninfectious or infectious1,6,14–16 (BOXES 1 and 2). Noninfectious disease processes account for most known causes of anterior uveitis.1 Lensinduced uveitis (LIU), trauma, idiopathic anterior uveitis, intraocular neoplasia, corneal ulceration, pigmentary uveitis of golden retrievers, and uveodermatologic syndrome are examples of noninfectious causes of anterior uveitis. Many of these etiologies can be identified by evaluation of signalment, history, and results of thorough physical and ocular examination. Investigation into possible infectious causes can be frustrating because it is difficult to make an etiologic diagnosis by ocular examination alone. Appropriate diagnostic testing can be performed based on the most likely diseases or syndromes for each case. Geographic location should also be considered when ranking etiologies, as some infectious diseases are more prevalent in certain areas. For example, blastomycosis is more common in young adult dogs in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, whereas coccidioidomycosis is more prevalent in the desert regions of the southwestern United States and protothecosis in the southeastern coastal regions.17 Vetlearn.com | November 2010 | Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® E3 FREE CE Canine Anterior Uveitis Box 2 FIGURE 2 Infectious Causes of Canine Anterior Uveitis1,6,14–16 Rickettsial • Ehrlichia canis • Rickettsia rickettsii Mycotic • Blastomyces dermatitidis • Histoplasma capsulatum • Coccidioides immitis • Cryptococcus neoformans • Aspergillus spp Algal • Prototheca zopfii • Prototheca wickerhamii Bacterial • Leptospira spp • Borrellia burgdorferi • Brucella canis • Bartonella vinsonii subsp berkhoffi • Bacteremia/septicemia6 Parasitic • Dirofilaria immitis14 • Leishmania spp15,16 • Toxocara spp1,6 Viral • Infectious canine hepatitis1 Noninfectious Causes of Anterior Uveitis Lens-Induced Uveitis Late immature cataract in a young mastiff resulting in lens-induced uveitis. Note the diffuse conjunctival hyperemia, epiphora, and miosis. There is a 360° corneal opacity at the limbus. 1+ aqueous flare (not seen in this photo) was detected via slit-lamp microscopy. Flash artifact can be seen. Anterior uveitis secondary to cataract formation can occur in patients with diabetes mellitus. These cataracts are bilaterally symmetrical and result from well-described alterations in the lens metabolic pathways.6 Due to their osmotic activity and rapidly progressive nature, canine diabetic cataracts result in lens intumescence and subsequent leakage of lens protein, leading to anterior uveitis.6 In phacoclastic LIU, zonal inflammation involving intra lenticular neutrophils and perilenticular fibroplasia develops following rupture of the lens capsule.19 Eyes examined early in the onset of clinical signs are likely to have fibrinopurulent anterior uveitis; older lesions are dominated by fibroplasia. Phacoclastic uveitis is resistant to antiinflammatory therapy but does respond to early removal of the injured lens.20 Features that may aid in the clinical diagnosis of phacoclastic uveitis include historical or physical evidence of ocular penetration, poor response to symptomatic therapy, and patient age (more prevalent in young dogs, some <1 year of age).19 Histopathology can aid in diagnosis because the zonal, perilenticular nature of inflammation, intralenticular leukocytes, and magnitude of fibroplasia are specific to uveitis secondary to lens capsular rupture.19 Spontaneous lens capsule rupture has been documented. Rupture is usually equatorial with varying degrees of associated phacoclastic uveitis in diabetic dogs with intumescent cataracts.21 Spontaneous posterior lens capsule rupture has also been observed in nondiabetic patients with cataracts.22 LIU is an inflammatory response of the ocular uvea to lens protein. Under normal conditions, a low concentration of circulating lens protein is chronically present in the eye to maintain immunologic tolerance to lens antigen by T cells.18 Two distinct types of LIU exist in dogs, phacolytic and phacoclastic.8,19 Phacolytic uveitis involves slow leakage of small amounts of lens protein through an intact lens capsule of a resorbing cataract (FIGURE 2).8,19 This incites a mild lymphocytic–plasmacytic anterior uveitis that can clinically resemble idiopathic uveitis.19 A presumptive etiologic diagnosis can be made by considering the history of cataract formation with subsequent development of anterior uveitis. Trauma This type of LIU is frequently observed in dogs presenting Uveal contusion and intraocular hemorrhage may occur secfor cataract surgery and often responds well to antiinflam- ondary to blunt or penetrating ocular trauma. Additional lesions include conjunctival hyperemia, corneal edema, iris matory therapy.19 E4 Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® | November 2010 | Vetlearn.com FREE Canine Anterior Uveitis CE vascular congestion, miosis, fibrin and cellular debris in the anterior chamber, and hypotony.6 The physical and ophthalmologic examination, a detailed history, and ultrasonographic imaging (if available) can aid in establishing the extent of ocular trauma. Idiopathic Idiopathic uveitis is diagnosed in almost 60% of dogs evaluated for anterior uveitis unrelated to trauma, hypermature cataract, neoplasia, or infectious disease.23 These dogs are generally middle-aged, spayed or neutered, and have no evidence of systemic disease. Unilateral ocular involvement is more likely with idiopathic anterior uveitis than with neoplastic or infectious causes.23 Idiopathic anterior uveitis with concurrent exudative retinal detachment has also been documented in dogs.24 This syndrome results in blindness; acute, severe bilateral choroiditis; and variable anterior uveitis with exudative retinal detachment. The etiopathogenesis of this syndrome is unknown, but it has been successfully treated with high dosages of corticosteroids. Ultimately, many patients require additional immunosuppressive therapy such as azathioprine or cyclosporine in combination with corticosteroids to control clinical signs (TABLE 2). A thorough diagnostic evaluation is necessary before initiating corticosteroid/immunosuppressive treatment to prevent exacerbation of infectious etiology or neoplastic process. table 2 Uveitis Drugs Used to Treat Canine Anterior 5,13,59,66 Drug Class Drug Dose Topical drugs Corticosteroids Prednisolone acetate (1% suspension) q1–12h NSAIDs Flurbiprofen (0.03% solution) q6–12h Suprofen (1% solution) q6–12h Ketorolac (0.5% solution) q6–12h Diclofenac (0.1% solution) q6–12h Mydriatic/cycloplegic drugs Atropine sulfate (0.5% and q8–24h 1% solution and ointment) Oral drugs Corticosteroids Prednisone or prednisolone 0.5 to 1 mg/kg bid Immunosuppressive drugs Cyclosporine 5 mg/kg bid; adjust dose pending 12-h whole blood trough level 48 h after initiation of therapy Azathioprine 2 mg/kg q12h for 2 weeks, then every other day for 2 weeks, then taper to 1 mg/kg every other day Carprofen ≤2.2 mg/kg q12–24h PRN Meloxicam ≤0.2 mg/kg once, then ≤0.1 mg/kg q24h thereafter Etodolac ≤15 mg/kg q24h Deracoxib ≤4 mg/kg q24h NSAIDs an underlying Neoplasia In one study, almost 25% of dogs evaluated for uveitis from 1989 to 2000 were diagnosed with neoplasia-associated uveitis.23 Older dogs make up this population; rottweilers are most commonly affected, followed by golden retrievers, Labrador retrievers, German shepherds, and mixed breeds. Ocular inflammation is a possible sequela of any intraocular neoplasm.6 Aqueous flare was the most common clinical sign observed in the study, but corneal edema, hyphema, and keratic precipitates were also documented.23 Although relatively rare, primary and secondary ocular neoplasms can cause anterior uveitis. Tumors of melanocytic origin are the most common primary ocular tumors in dogs, followed by epithelial tumors of the ciliary body.6,25 Melanocytic tumors may have a heritable basis in Labrador retrievers.6 Recent evidence has suggested that limbal melanomas, caudal anterior uveal melanomas, and ocular melanosis in golden retrievers may also be partly heritable, with the same genetic mutation(s) causally associated with melanocytic disease at different ocular sites.26 Uveal melanomas, whether benign or malignant, almost always arise from the anterior uveal tract and have a low incidence of metastasis.6,25 Iridal and ciliary body neoplasms are usually heavily pigmented and have a low risk of metastasis.27,28 Lymphoma is the most common secondary neoplasm23,25 of the canine globe, followed by hemangiosarcoma, mammary carcinoma, and oral malignant melanoma.25 Lymphoma may cause inflammation, iridal thickening, hypopyon, hyphema, and glaucoma.4 Cytologic samples for diagnosis may be procured via aqueocentesis or hyalocentesis if thorough staging or peripheral lymph node aspiration does not suffice. Alternatively, tissue may be submitted for histopathologic evaluation following enucleation. Other tumors Vetlearn.com | November 2010 | Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® E5 FREE CE Canine Anterior Uveitis known to metastasize to the eye include seminoma, transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder and/or urethra, transmissible venereal tumor, anaplastic fibrosarcoma, neurogenic sarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, and pheochromocytoma.6 Bilateral ocular involvement may occur, and varying degrees of anterior uveitis and its sequelae may be the presenting signs.6 One case of intraocular osteosarcoma causing anterior uveitis in a 10-year-old German shepherd has been documented.29 Corneal Ulceration Anterior uveitis may occur as an extension of a local process such as scleritis or keratitis.8 It has been proposed that an axonal reflex mechanism may be responsible for vasodilatation and inflammation of the uvea when ulcerative keratitis is present.8 Breed-Specific Uveitis Some patients develop generalized vitiligo and/or poliosis. Rapidly depigmenting areas tend to become ulcerated and crusted. Ocular histopathology primarily reveals panuveitis, retinal separation, and prominent pigment-containing macrophages.6 Skin histopathology reveals interface dermatitis with a primarily lichenoid pattern, large histiocytic cells, plasma cells, and small mononuclear cells.6 Treatment involves topical or subconjunctival cortico steroids, cycloplegics (atropine), and systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, 1 to 2 mg/kg/d PO) to treat inflammation and dermatologic signs.34 Recurrence is common, and combination therapy consisting of oral corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive drugs (e.g., azathioprine, 2 mg/kg/d) may be necessary.6 Oral cyclosporine is a reasonable alternative to azathioprine when combined with corticosteroids to control inflammation (TABLE 2). Topical administration of cyclosporine can be considered, but this drug cannot penetrate an intact cornea. Pigmentary uveitis of golden retrievers is presumed to be an inherited form of anterior uveitis. It presents as adhe- Infectious Causes of Anterior Uveitis sions between the iris and lens or peripheral iris and cornea, In a recent retrospective study23 of dogs with anterior uveitis, with pigment dispersion across the anterior lens capsule.30 17.6% were diagnosed with an infectious etiology. In genThis form of anterior uveitis is not associated with any sys- eral, tick-borne, fungal, algal, and bacterial agents should be temic disorder or infectious etiology.31 The most frequently suspected when evaluating a patient for infectious causes of observed early clinical sign is pigment on the anterior lens anterior uveitis.23 Other systemic signs may accompany ocucapsule.32 Other clinical signs associated with this disorder lar manifestations, such as generalized lymphadenopathy, include aqueous flare, uveal cysts, fibrin in the anterior pancytopenia, thrombocytopenia, diarrhea, and draining chamber, posterior synechiae, secondary glaucoma, corneal skin lesions.23 Standard-of-care therapy for these etiologic ulcer, hyphema, iris bombé, phthisis bulbi, retinal degen- agents is briefly discussed here; a more thorough discussion eration or detachment, and uveal neoplasia.32 Diagnosis is of treatment can be found in veterinary internal medicine or based on exclusion of other underlying etiologies. The prog- canine infectious disease texts. nosis is guarded because this disease is progressive and Tick-Borne Disease predisposes to secondary glaucoma.32 Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis is a tick-borne disease caused Uveodermatologic Syndrome by the rickettsial pathogen Ehrlichia canis. E. canis is transUveodermatologic syndrome is a debilitating disease result- mitted primarily by the brown dog tick (Rhipicephalus ing in blindness in many affected dogs.33 Due to its similari- sanguineus) and the American dog tick (Dermacentor varities to Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada (VKH) syndrome in humans, abilis). Ocular lesions are common, and the severity of signs this disease is commonly known as VKH-like disease.6 The varies.35 Ocular signs include conjunctivitis, conjunctival/ cause is unknown, but an immune-mediated etiology is iridal petechiae and ecchymoses, corneal edema, panuveitis, strongly suspected.33 A slightly greater incidence in males hyphema, secondary glaucoma, optic neuritis, and retinal has been suggested, with a likely immunogenetic predis- hemorrhage with detachment.36 Diagnosis of ehrlichiosis position, evidenced by occurrence of this disease in Akitas, requires visualization of morulae, detection of E. canis antibodies, or PCR amplification of E. canis DNA.37 Samoyeds, Siberian huskies, and Shetland sheepdogs.6 Ocular signs are usually the first abnormality noted, with Ocular manifestations can also occur with Rocky Mountain most patients being referred for acute-onset blindness or spotted fever (RMSF). RMSF is caused by Rickettsia rickchronic anterior uveitis.34 Ocular findings range from bilat- ettsii, a gram-negative, obligate intracellular coccobacillus eral anterior uveitis to severe panuveitis, retinal detachment, transmitted primarily by the D. variabilis tick in the eastern posterior synechiae, secondary glaucoma, cataract, and United States and Dermacentor andersonii in the western vision loss.34 Depigmentation of the hair and skin usually United States and Canada. Ocular involvement occurs secfollows the onset of ocular signs. The eyelids, nasal pla- ondary to vasculitis.38 Clinical signs include conjunctival num, lips, scrotum, and footpads are often affected; depig- vascular injection, anterior uveitis, petechial hemorrhages of mented areas can be generalized or restricted to the face.34 the iris stroma, and bilateral hyphema.39 E6 Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® | November 2010 | Vetlearn.com FREE Canine Anterior Uveitis CE An immunofluorescence assay (IFA) detects IgM and IgG and is the “gold standard” in the diagnosis of RMSF. A single IFA titer of 1:64 or higher for IgM with concurrent clinical signs is considered diagnostic.38 A fourfold rise in IgG between acute and convalescent specimens acquired 3 to 4 weeks apart is also considered diagnostic.38 Standard therapy of ehrlichiosis and RMSF consists of routine supportive care and doxycycline at a minimum dose of 10 mg/kg/d for 28 days, but 7 days of administration has been shown to be sufficient for RMSF.37,40 Tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are also effective in treating RMSF.38 Fungal Disease Key Facts • Canine anterior uveitis is a common ocular disorder that is usually idiopathic but can be associated with multiple, serious systemic diseases. • It can be difficult to distinguish among the various etiologies of canine anterior uveitis because the eye is limited in its ability to respond to injury. • A thorough history, physical and ocular examinations, and routine database (complete blood cell count, serum chemistry analyses, urinalysis) should be obtained to direct subsequent diagnostic testing and establish a definitive diagnosis. Systemic mycoses can cause anterior or posterior uveitis or panuveitis. Infection with Blastomycosis dermatitidis • Immediate, aggressive therapy is necessary to stop is the systemic mycosis most commonly associated with inflammation, prevent and control complications ocular lesions.12 Approximately 30% to 43% of dogs with secondary to inflammation (glaucoma, cataract systemic blastomycosis have clinical signs of ocular involveformation, retinal degeneration), relieve pain, and ment.41 Common ocular abnormalities include conjunctival preserve vision. hyperemia, corneal edema, aqueous flare, iritis, iridocyclitis, vitritis, retinitis, chorioretinitis, serous or granulomatous retinal separation, optic neuritis, secondary glaucoma, and rhagic enteritis as the most common clinical sign.46 However, blindness.42 Other fungal organisms proved or suspected to canine protothecosis can present with acute blindness as cause anterior uveitis in dogs include Coccidioides immi- the only sign.47 tis, Cryptococcus neoformans, Aspergillus fumigatus, and In one study, ocular involvement was present in 77% of Histoplasma capsulatum.6,43 All disseminated mycoses result cases of systemic protothecosis.46 Aqueous flare, iritis, episin posterior segment disease, but coccidioidomycosis and cleral injection, epiphora, conjunctival hyperemia, low IOP, cryptococcosis predominantly cause posterior segment dis- and hyphema have also been documented.47 Diagnosis is confirmed by direct visualization of the organism, cytologic ease without anterior segment involvement.12 Organisms can be detected by cytopathology of body examination of rectal scrapings, aqueocentesis, or histofluids, lymph node aspirates, vitreous humor, or impression pathologic examination of tissue specimens from the colon smears of skin lesions or by histopathologic examination of or regional lymph nodes.46 various tissues, including enucleated eyes.44 Direct visualiza- Successful therapy has yet to be discovered for proto tion of the organism remains the gold standard for diagnosis, thecosis.46 Amphotericin B has been successful in slowing but serology may be useful to aid in supporting a diagnosis disease progression but has not been curative.45 Amphotericin B (1 mg/kg IV three times weekly to a cumulative dose of when organisms cannot be identified. Systemic blastomycosis with ocular involvement is treated 12 mg/kg) used in combination with ketoconazole, fluconwith itraconazole at a dose of 5 mg/kg/d PO for a minimum azole, or itraconazole (5 to 10 mg/kg/d PO) is an option for of 60 to 90 days or at least 30 days beyond resolution of long-term therapy of P. zopfii infection, but the prognosis clinical signs.44 Treatment durations of 6 to 12 months are remains grave.46 not unusual. Enucleation may be necessary if severe secondary glaucoma develops.42 Histoplasmosis can be treated Bacterial and Protozoal Disease with itraconazole (10 mg/kg/d PO) or with amphotericin B.44 Leptospirosis has been documented as a cause of panuveitis Fluconazole is the initial drug of choice for coccidioidomy- in one case, with mild hyphema, aqueous flare, and partial cosis (10 mg/kg PO bid) and cryptococcosis (2.5 to 5 mg/kg serous retinal detachments bilaterally.48 Diagnosis can be obtained by evaluation of acute and convalescent microPO or IV daily or bid).44,45 scopic agglutination titers (MATs) for the various Leptospira Protothecosis serovarieties. PCR can be performed on blood and urine to Prototheca spp are colorless algae related to the green algae detect leptospiral genetic material. Appropriate clinical signs of the genus Chlorella. Of the four recognized or proposed with elevated serum MATs are the gold standard in diagnospecies, Prototheca zopfii and Prototheca wickerhamii have sis.49 Penicillin (25,000 to 40,000 U/kg q12–24h IV or IM for been found to be pathogenic.46 In dogs, protothecosis usu- 14 days), ampicillin (22 mg/kg PO, SC, or IV q8–12h for 14 ally presents as a systemic infection, with protracted hemor- days), or amoxicillin (22 mg/kg PO q8h for 14 days) is given Vetlearn.com | November 2010 | Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® E7 FREE CE Canine Anterior Uveitis to eliminate leptospiremia, followed by doxycycline (5 to 10 secondary glaucoma, and analgesia.8,12 Specific therapies mg/kg PO bid) for 14 days to eliminate the organism from address etiologic agents or contributing factors (e.g., conthe renal tubular cells.50,51 Appropriate therapy is essential junctival or corneal foreign body, corneal ulcer, anterior or because infected animals pose a zoonotic threat to human posterior lens luxation) discovered during the initial diagcaretakers.50 nostic evaluation. Nonspecific therapy comprises decreas Animals infected with Borrelia burgdorferi can present ing intraocular inflammation, inducing mydriasis to prevent with anterior uveitis.52 Uveal inflammation should therefore synechia formation, and initiating cycloplegia to alleviate prompt the clinician to evaluate for borreliosis if other com- pain (TABLE 2). mon causes are eliminated. Brucella canis, a gram-negative Antiinflammatory drug therapy (corticosteroids and coccobacillus found in the vaginal fluid or urine of infected NSAIDs) is an extremely important consideration in treatdogs, can also produce anterior uveitis.53 Serology can be ing anterior uveitis regardless of its cause because failure to employed in the diagnosis of either borreliosis or brucel- control inflammation leads to serious complications. Topical losis. Doxycycline (10 mg/kg q24h PO for 21 to 28 days) or or systemic administration depends on drug formulation, β-lactam antibiotics such as amoxicillin (22 mg/kg q12h PO severity of clinical signs, and location of inflammation.13 Anterior uveitis is initially treated topically, but if the inflamfor 21 to 28 days) are effective treatments.54 Bartonella spp have been implicated in causing anterior mation remains poorly controlled by topical treatment alone, uveitis.55 In one case, a 2-year-old, spayed spaniel mix was systemic therapy may be required.58 evaluated for bilateral anterior uveitis. All infectious dis- Corticosteroids are the drugs most commonly used to ease titers were normal, except for a 1:512 antibody titer control ocular inflammation, but they are contraindicated to Bartonella vinsonii subsp berkhoffi. Ocular changes in the presence of ulcerative or infectious keratitis.59 Topical attributable to bartonellosis include optic neuritis, anterior corticosteroids can be used to treat anterior uveitis assouveitis, vitritis, pars planitis, focal and multifocal retinal ciated with systemic infectious disease without significant vasculitis, retinal white dot syndrome, branch retinal arte- exacerbation of the infectious process.59 Prednisolone aceriolar or venous occlusions, focal choroiditis, serous reti- tate achieves a high intraocular concentration and is the drug nal detachments, papillitis, and peripapillary angiomatous of choice for anterior uveitis.60 Topically, it is administered lesions.55 Clinical improvement was linked with a posttreat- as a 1% suspension. Frequency of administration depends ment decrease in B. vinsonii subsp berkhoffi seroreactivity. on the severity, location, and etiology of the disease proLong-term antibiotic administration (4 to 6 weeks) may be cess. One to six times daily up to hourly administration has necessary to eliminate infection.56 Macrolides (erythromycin, been advocated for the suspension.5,13,59 Effective treatment azithromycin), fluoroquinolones (alone or in combination results in normalization of IOP and decreased photophobia, with amoxicillin), and doxycycline are the initial drugs of blepharospasm, discharge, keratitis, and aqueous flare.59 choice for treating B. vinsonii subsp berkhoffi infection in Systemic corticosteroids may be necessary to supplement topical therapy when treating severe cases of anterior dogs.56 Bacteremia or septicemia from any local or generalized uveitis. These drugs have minimal effects on most forms infectious process may result in anterior uveitis. Common of keratitis and control intraocular inflammation when topietiologies of ocular inflammation include pyometra, pros- cal corticosteroids are contraindicated.61 Although not pretatitis, neonatal umbilical infections, abscesses, bacterial viously reported, I (E. A.) have observed several cases of melting corneal ulcers in dogs receiving immunosuppresendocarditis, dental/oral infections, and pyelonephritis.6,12 Ocular leishmaniasis, although rare in the United States, sive doses of systemic corticosteroids. These patients should is known to cause anterior uveitis.12,57 Cases have been be monitored for the development of ulcerative keratitis. reported in Texas, Maryland, and Oklahoma, and anti- Therapy is instituted at a higher dose to suppress inflammaleishmanial antibodies have been detected in asymptom- tion, followed by drug tapering for long-term maintenance. atic animals in Alabama and Michigan.16 Although ocular The recommended initial dose is 0.5 mg/kg PO bid for leishmaniasis is infrequently diagnosed in the United States, antiinflammatory effects, up to 1 mg/kg PO bid for immuactive military dogs or dogs with travel history to or from nosuppressive effects.59 The dose can then be decreased endemic areas such as Europe, Africa, Asia, and Central and incrementally based on patient response. When an infectious disease is suspected, systemic corticosteroids should South America should be screened for this disease.12 be used with caution because of their immunosuppressive Treatment effects. Appropriate antimicrobial therapy is recommended Primary therapeutic objectives for treatment of anterior if systemic corticosteroid administration is required in the uveitis should include treatment or elimination of any spe- presence of a bacterial infection. cific etiology, reduction and control of inflammation, pres- Available topical ophthalmic NSAIDs include suprofen ervation of a functional pupil, prevention or treatment of (1%), diclofenac (0.1%), flurbiprofen (0.03%), and ketorolac E8 Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® | November 2010 | Vetlearn.com FREE Canine Anterior Uveitis CE (0.5%). Flurbiprofen and suprofen are similar in their ability to reduce ocular inflammation.62 Flurbiprofen is well absorbed into ocular tissues, concentrates in the cornea, and has low systemic absorption.63 It can be used in conjunction with topical corticosteroids. Adverse effects include topical irritation and possible hemorrhage as a result of interference with platelet aggregation.64 Choices for injectable or oral NSAIDs include aspirin, acetaminophen, piroxicam, ketoprofen, meloxicam, carprofen, etodolac, and deracoxib. These drugs are commonly used for treatment of anterior uveitis when corticosteroids are contraindicated.65 Gastrointestinal effects and hepatopathy are the most significant adverse effects of their use.66 Keratoconjunctivitis sicca has been reported in dogs receiving oral etodolac.67 Cycloplegic drugs relieve pain by preventing ciliary body and iris muscle spasms, whereas mydriatic drugs prevent or break down posterior synechiae by dilating the pupil and decreasing iris–lens contact.13 Cycloplegia and mydriasis can be accomplished by using a parasympatholytic agent such as atropine sulfate. Atropine is a direct-acting parasympatholytic agent that blocks the postganglionic cholinergic receptor response, resulting in mydriasis, cycloplegia, and decreased tear production.59 It is often the drug of choice in management of inflammation of the anterior segment.59 Much of the pain associated with anterior uveitis is a result of inflammation and subsequent spasm of the iridal and ciliary body musculature.59 Atropine paralyzes these muscles, decreasing discomfort. Atropine also stabilizes the BAB.5,60 Topical atropine sulfate is formulated in a 1% ointment or solution. Duration and frequency of application depend on the severity of inflammation. Mild inflammation may require once-daily administration, whereas severe inflammation may require treatment three to four times a day.13 Atropine is contraindicated in glaucoma; therefore, IOP should be measured during the course of atropine therapy and immediately discontinued if evidence of glaucoma is observed.5,59 Complications and Prognosis Intraocular inflammation can have many deleterious sequelae; therefore, treatment should be prompt, aggressive, and appropriate. Synechiae formation can lead to glaucoma by obstructing aqueous humor flow through the pupil or iridocorneal angle. Development of secondary glaucoma should be suspected when IOP is >10 mm Hg in eyes with anterior uveitis.13 Anterior uveitis may cause cataracts, the extent of which depends on the severity and duration of inflammation. Corneal endothelial damage from chronic anterior uveitis can cause corneal edema, often followed by deep corneal vascularization and scarring.8 The prognosis depends on the location, extent, and duration of inflammation; underlying cause; secondary compli- cations; and timeliness/adequacy of treatment.12 Chances of recovery are greatest when the inflammation is mild to moderate and a treatable underlying cause can be found. Severe, recurrent anterior uveitis typically carries the poorest long-term prognosis.12 Systemic spirochetal and rickettsial infections have a good prognosis if treated promptly and aggressively, whereas the prognosis for systemic mycotic/ algal infections and uveodermatologic syndrome is guarded to poor.12 The prognosis is good for most canine primary intraocular neoplasms because they are usually benign, whereas the outlook for multicentric or metastatic intraocular neoplasia remains guarded.6,12 Conclusion Canine anterior uveitis is a complex ocular disorder with several etiologies. Understanding the pathophysiology, clinical signs, and potential etiologies can guide clinicians to a prompt, accurate diagnosis and appropriate therapy. Proper treatment is essential to alleviate patient discomfort, produce rapid recovery, and prevent secondary complications and permanent undesirable sequelae that may result in blindness or enucleation. References 1. Gwinn RM. Anterior uveitis: diagnosis and treatment. Semin Vet Med Surg (Small Anim) 1988;3(1):33-39. 2. Glaze MB. Ocular manifestations of systemic disease. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XI. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1992:1061-1070. 3. Powell CC, Lappin MR. Causes of feline uveitis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2001;23(2):128-141. 4. Swanson JF. Ocular manifestations of systemic disease in the dog and cat. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1990;20(3):849-867. 5. Van der Woerdt A. Management of intraocular inflammatory disease. Clin Tech Small Anim Pract 2001;16(1):58-61. 6. Diseases and surgery of the canine anterior uvea. In: Gelatt KN. Essentials of Veterinary Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2000:197-225. 7. Millichamp NJ, Dziezyc J. Mediators of ocular inflammation. Prog Vet Comp Ophthalmol 1991;1(1):41-58. 8. Hakanson N, Forrester S. Uveitis in the dog and cat. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1990;20(3):715-735. 9. Howes EL Jr. Basic mechanisms of pathology. In: Spencer WH, ed. Ophthalmic Pathology, an Atlas and Textbook. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1985:Vol. 1:1-108. 10.Hendrix DVH. Differential diagnosis of the red eye. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XIII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:1042-1045. 11.Peiffer RL Jr, Wilcock BP, Yin H. The pathogenesis and significance of pre-iridal fibrovascular membrane in domestic animals. Vet Pathol 1990;27(1):41-45. 12.Kern TJ. Canine uveitis. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995:1248-1253. 13.Powell CC, Lappin MR. Diagnosis and treatment of feline uveitis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2001;23(3):258-266. 14.Carastro SM, Dugan SJ, Paul AJ. Intraocular dirofilariasis in dogs. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1992;14(2):209-215. 15.Torrent E, Leiva M, Segales J, et al. Myocarditis and generalized vasculitis associated with leishmaniosis in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 2005;46:549-552. 16.Ciaramella P, Corona M. Canine leishmaniasis: clinical and diagnostic aspects. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2003;25(5):358-368. 17.Gilger BC. Ocular manifestations of systemic infectious diseases. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XIII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:276-279. 18.Woerdt A, Nasisse MP, Davidson MG. Lens-induced uveitis in dogs: 151 cases (1985-1990). JAVMA 1992;201(6):921-926. 19.Wilcock BP, Peiffer RL Jr. The pathology of lens-induced uveitis in dogs. Vet Pathol 1987;24:549-553. 20.Slatter DH. Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1981:439. 21.Wilkie DA, Gemensky-Metzler AJ, Colitz CMH, et al. Canine cataracts, diabetes Vetlearn.com | November 2010 | Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® E9 FREE CE Canine Anterior Uveitis mellitus and spontaneous lens capsule rupture: a retrospective study of 18 dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 2006;9:328-334. 22.Davidson MG, Nelms SR. Diseases of the canine lens and cataract formation. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary Ophthalmology. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing; 2007:859881. 23.Massa KL, Gilger BC, Miller TL, et al. Causes of uveitis in dogs: 102 cases (19892000). Vet Ophthalmol 2002;5(2):93-98. 24.Gwin RM, Wyman M, Ketring K, et al. Idiopathic uveitis and exudative retinal detachment in the dog. JAAHA 1980;16:163-170. 25.Dubielzig RR. Ocular neoplasia in small animals. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1990;20(3):837-848. 26.Donaldson D, Sansom J, Scase T, et al. Canine limbal melanoma: 30 cases (19922004). Part 1. signalment, clinical and histological features and pedigree analysis. Vet Ophthalmol 2006;9(2):115-119. 27.Diters RW, Dubielzig RR, Aguirre GD, et al. Primary ocular melanoma in dogs. Vet Pathol 1983;20:379-395. 28.Wilcock BP, Peiffer RL. Morphology and behavior of primary ocular melanomas in 91 dogs. Vet Pathol 1986;23:418-424. 29.Van de Sandt RROM, Boeve MH, Stades FC, et al. Intraocular osteosarcoma in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 2004;45:372-374. 30.Ocular Disorders Presumed to be Inherited in Purebred Dogs. 2nd ed. Phoenix, AZ: Genetic Committee of the American College of Veterinary Ophthalmologists; 1996. 31.Sapienza JS. Pigmentary uveitis in golden retrievers: 43 cases. Proc Annu Meet ECVO 1998:33. 32.Sapienza JS, Domenech FJS, Prades-Sapienza A. Golden retriever uveitis: 75 cases (1994-1999). Vet Ophthalmol 2000;3:241-246. 33.Angles JM, Famula TR, Pedersen NC. Uveodermatologic (VKH-like) syndrome in American Akita dogs is associated with an increased frequency of DQA1*00201. Tissue Antigens 2005;66(6):656-665. 34.Morgan RV. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome in humans and dogs. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1989;11(10):1211-1216. 35.Martin CL. Ocular manifestations of systemic disease. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary Ophthalmology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:1401-1504. 36.Leiva M, Naranjo C, Pena MT. Ocular signs of canine monocytic ehrlichiosis: a retrospective study in dogs from Barcelona, Spain. Vet Ophthalmol 2005;8(6):387-393. 37.Neer TM, Harrus S. Canine monocytic ehrlichiosis and neorickettsiosis (E. canis, E. chaffeensis, E. ruminatium, N. sennetsu, and Risticii infections). In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2006:203217. 38.Low RM, Holm JL. Canine rocky mountain spotted fever. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2005;27(7):530-538. 39.Davidson MG, Breitschwerdt EB, Nasisse MP, et al. Ocular manifestations of RMSF in dogs. JAVMA 1998;194(6):777-781. 40.Neer TM, Breitschwerst EB, Greene RT, Lappin MR. 2002 Consensus statement on ehrlichial disease of small animals from the Infectious Disease Study Group of the ACVIM. American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine. J Vet Intern Med 2002;16:309315. 41.Hendrix DVH, Rohrbach BW, Bochsler PN, et al. Comparison of histologic lesions of endophthalmitis induced by Blastomyces dermatitidis in untreated and treated dogs: 36 cases (1986-2001). JAVMA 2004;224(8):1317-1322. 42.Bloom JD, Hamor RE, Gerding PA. Ocular blastomycosis in dogs: 73 cases, 108 eyes (1985-1993). JAVMA 1996;209(7):1271-1274. 43.Gelatt KN, Chrisman CL, Samuelson DA, et al. Ocular and systemic aspergillosis in E10 a dog. JAAHA 1991;27:427-431. 44.Legendre AM, Toal RL. Diagnosis and treatment of fungal disease of the respiratory system. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XIII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:815-819. 45.Cryptococcosis. In: Greene CE, ed. Infectious Diseases of the Dog and Cat. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2006:584-598. 46.Strunck E, Billups L, Avgeris S. Canine protothecosis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2004;26(2):96-102. 47.Schultze AE, Ring RD, Morgan RV, et al. Clinical, cytologic and histopathologic manifestations of protothecosis in two dogs. Vet Ophthalmol 1998;1:239-243. 48.Townsend WM, Stiles J, Krohne SG. Leptospirosis and panuveitis in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol 2006;9(3):169-173. 49.Sessions JK, Greene CG. Canine leptospirosis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and diagnosis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2004;26(8):606-622. 50.Ross LA, Rentko V. Leptospirosis. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XIII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:308-310. 51.Sessions JK, Greene CE. Canine leptospirosis: treatment, prevention, and zoonosis. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 2004;26(9):700-706. 52.Munger RJ. Uveitis as a manifestation of Borrelia burgdorferi infection in dogs. JAVMA 1990;197(7):811. 53.Wanke MM. Canine brucellosis. Anim Reprod Sci 2004;82-83:195-207. 54.Appel MJG, Jacobson RH. CVT update: canine lyme disease. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995:303-309. 55.Michau TM, Breitschwerdt EB, Gilger BC, et al. Bartonella vinsonii subspecies berkhoffi as a possible cause of anterior uveitis and choroiditis in a dog. Vet Ophthalmol 2003;6(4):299-304. 56.Breitschwerdt EB. Canine bartonellosis. In: Ettinger JE, Feldman EC, eds. Textbook of Veterinary Internal Medicine. St. Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2005:636-637. 57.Swenson CL, Silverman J, Stromberg PC, et al. Visceral leishmaniasis in an English Foxhound born and raised in an Ohio research colony. JAVMA 1988;193:1089-1092. 58.Collins, BK, Moore CP. Diseases and surgery of the canine anterior uvea. In: Gelatt KN, ed. Veterinary Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999:755-795. 59.Wilkie DA. Control of ocular inflammation. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1990;20(3):693-713. 60.Corticosteroid therapy. In: Havener WH. Ocular Pharmacology. 5th ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1983:223-235, 333-334, 433-500. 61.Slatter DH. Fundamentals of Veterinary Ophthalmology. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1981. 62.Stark WJ, Fagadau WR, Stewart RH, et al. Reduction of pupillary constriction during cataract surgery using suprofen. Arch Ophthalmol 1986;104:364-366. 63.Anderson JA, Chen CC, Vita JB, et al. Disposition of topical flurbiprofen in normal and aphakic rabbit eyes. Arch Ophthalmol 1982;100:642-645. 64.Feinstein NC, Rubin B. Toxicity of flurbiprofen sodium. Arch Ophthalmol 1988;106:311. 65.Miller TR. Anti-inflammatory therapy of the eye. In: Bonagura JD, ed. Kirk’s Current Veterinary Therapy XII. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995:1218-1222. 66.Giuliano EA. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in veterinary ophthalmology. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 2004;34(3):707-723. 67.Klauss G, Giuliano EA, Moore CP, et al. Keratoconjunctivitis sicca associated with administration of etodolac in dogs: 211 cases (1992-2002). JAVMA 2007;230(4):541547. Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® | November 2010 | Vetlearn.com FREE Canine Anterior Uveitis CE 3 CE CREDITS CE Test This article qualifies for 3 contact hours of continuing education credit from the Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine. To take individual CE tests online and get real-time scores, visit Vetlearn.com. Those who wish to apply this credit to fulfill state relicensure requirements should consult their respective state authorities regarding the applicability of this program. 1. Canine anterior uveitis a. presents with distinctive clinical signs. b. is almost always associated with a systemic infectious disease. c. is commonly idiopathic. d. can be treated effectively, easily, and with a low risk of complications. 2. The BAB a. is impermeable to constituents within blood and plasma. b. is not affected in patients with anterior uveitis. c. is composed of loosely adherent cells of the ciliary body and iridal blood vessels. d. leaks fluid, protein, and cells into the aqueous humor when compromised by inflammation, resulting in aqueous flare. 3. Which of the following is not a common mechanism responsible for ocular tissue injury resulting in anterior uveitis? a. damage to ocular tissue by infectious organisms b. topical drug administration c. immune-mediated mechanisms d. neoplastic invasion 4. ________ is not a diagnostic differential for anterior uveitis. a. Endothelial dystrophy b. Glaucoma c. Ulcerative keratitis d. Conjunctivitis 5. Which statement regarding aqueous flare is true? a. It is caused by increased protein and/or cells in the aqueous humor as a result of a disrupted BAB and is pathognomonic for anterior uveitis. b. It does not occur in dogs. c. It is caused by BAB breakdown in the iridocorneal angle. d. It occurs only when glaucoma is present. 6. The most common secondary ocular neoplasm in dogs is a. hemangiosarcoma. b. osteosarcoma. c. malignant melanoma. d. lymphoma. 7. Ocular blastomycosis a. can be ruled out by serology. b. can be treated inexpensively and rapidly. c. is best diagnosed by direct visualization of fungal organisms. d. always results in enucleation of the affected eye. 8. Which statement regarding treating uveitis is true? a. Nonspecific therapy should never be employed until a definitive diagnosis is made. b. The primary goal should be to stop inflammation, relieve pain, and prevent or control complications. c. Oral corticosteroids are preferred over topical corticosteroid administration. d. Atropine is always recommended to relieve ocular discomfort. 9. Which statement regarding topical drug therapy for treating canine anterior uveitis is false? a. Prednisolone acetate suspension (1%) is a potent topical corticosteroid used in the treatment of canine anterior uveitis. b. Topical NSAIDs can be used in conjunction with topical corticosteroids. c. Atropine relieves ocular pain by relaxing uveal muscle spasm. d. Hemorrhage due to interference with platelet aggregation is not a side effect of topical NSAID application. 10.Which statement regarding complications of anterior uveitis is true? a. Anterior uveitis rarely results in the development of glaucoma. b. Development of secondary glaucoma should be suspected when IOP is >10 mm Hg in eyes with anterior uveitis. c. Anterior uveitis does not cause cataracts. d. Development of blindness is a concern only with chorioretinitis, not anterior uveitis. Vetlearn.com | November 2010 | Compendium: Continuing Education for Veterinarians® E11 ©Copyright 2010 MediMedia Animal Health. This document is for internal purposes only. Reprinting or posting on an external website without written permission from MMAH is a violation of copyright laws.