* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Hypertension in Pregnancy: Management Strategies

Survey

Document related concepts

Birth control wikipedia , lookup

Epidemiology of metabolic syndrome wikipedia , lookup

Women's health in India wikipedia , lookup

Reproductive health wikipedia , lookup

HIV and pregnancy wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal development wikipedia , lookup

Women's medicine in antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Maternal health wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal testing wikipedia , lookup

Prenatal nutrition wikipedia , lookup

Fetal origins hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Pre-eclampsia wikipedia , lookup

Maternal physiological changes in pregnancy wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

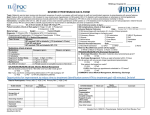

Chapter for ‘Cardiology update’ 2014 Hypertension in Pregnancy: Management Strategies. Dr. Vitull K. Gupta MD (Medicine), Associate Professor, Adesh Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Bathinda, Punjab. Email: [email protected] Dr. Sonia Arora, MBBS, DNHE, Senior Consultant, Diet and Nutrition, Kishori Ram Hospital and Diabetes Carte Centre, Bathinda, Punjab. Meghna Gupta MBBS (Std), Adesh Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Bathinda, Punjab. Introduction: About four thousand years ago people realized that there are two main mortal things: hemorrhage and toxemia, unique to pregnancy causing childbirth related deaths. Toxemia was thought to be some kind of toxin causing seizures, swelling and death from the beginning of the third trimester to a month or so beyond delivery. Eclampsia was described by Celsus in 100 AD as seizures during pregnancy that abated with delivery1. As medical science progressed it was termed as Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy(HDP), Hypertension in Pregnancy(HIP) or pregnancy induced hypertension(PIH). Hypertension(HTN) is the most common medical problem encountered during pregnancy worldwide. HDP occur in women with pre-existing primary or secondary chronic HTN, and in women who develop new-onset HTN in the second half of pregnancy.2 Prompt identification and appropriate management of HDP are essential for optimal outcomes because HDP: Are associated with severe maternal obstetric complications and increased maternal mortality risk. 3 Lead to preterm delivery, fetal intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR), low birth weight and perinatal death.4 An estimated 8-10% pregnancy is complicated by hypertensive disorders and about 25% of all antenatal admissions are due to HTN related complications4 5 and is a leading cause of maternal and fetal morbidity, particularly when the elevated blood pressure (BP) is due to preeclampsia, either alone (pure) or “superimposed” on chronic vascular disease. 6 7 They are responsible for 8-9% of maternal deaths in India and 15 -20% of maternal deaths in western world. Even in the current millennium, HDP remain among the most understudied areas and one of the lowest recipient of research funds compared with other diseases in terms of disability adjusted life years8 which underscoring decades of controversies surrounding classification, diagnosis and management of HDP. In reviewing the literature, one is faced with difficulties regarding definitions and classifications used to categorize HTN in pregnant women.9 10 While there is general consensus across guidelines for most major definitions, there are some noteworthy differences in definitions and criteria for severity stratification which are not in the preview of this chapter. More over, in absence of RCTs, recommendations can only be guided by expert opinion.11 Definition: Hypertension: HTN in pregnancy is defined as a systolic blood pressure(SBP) ≥140 or DPB ≥90mmHg or both. There is consensus across most guidelines and Guideline Development Group (GDG) has defined mild, moderate and severe HTN.2 Mild hypertension: SBP 140-149mmHg, DBP 90–99mmHg. Moderate hypertension: SBP 150-159mmHg, DBP 100–109mmHg. Severe hypertension: SBP >160mmHg, DBP >110 mmHg. Classification of HDP: 2 12 13 14 15 16 HDP are comprised of a spectrum of disorders typically classified into 4 categories: Chronic (preexisting) hypertension, Gestational hypertension, Preeclampsia (including chronic (preexisting) HTN with superimposed preeclampsia). Eclampsia. Chronic Hypertension: Chronic (preexisting) HTN is defined as HTN (SBP ≥140mmHg or DBP ≥90mmHg or both) that is present before 20 weeks of gestation or prior to pregnancy documented on more than one occasion. Gestational Hypertension: Gestational HTN is defined as new HTN (SBP ≥140mmHg or DBP ≥90mmHg or both) presenting at or after 20 weeks gestation without proteinuria or other features of preeclampsia and followed by normalization of BP postpartum. This terminology replaces the term “PIH” that was widely used in older guidelines and literature. Preeclampsia and chronic (preexisting) HTN with superimposed preeclampsia: Preeclampsia is defined as HTN plus significant proteinuria (24 hour urine protein >300 mg), specifically gestational HTN plus new onset proteinuria, or chronic (preexisting) HTN with new or worsening proteinuria classified as chronic (preexisting) HTN with superimposed preeclampsia. Preeclampsia can also occur without proteinuria, with hepatic, hematopoietic, or other manifestations. Edema is no longer considered a specific diagnostic criterion for preeclampsia. Eclampsia: Eclampsia is defined as new onset grand mal seizures in women with preeclampsia. Eclampsia can manifest without preeclampsia and also in post-partum period. HELLP syndrome: HELLP syndrome is a serious systemic disorder associated with preeclampsia and manifested by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and a low platelet count. HELLP syndrome can manifest with or without proteinuria. Management Strategies: The goal of management strategies in HDP is to optimize pregnancy outcome, which requires consideration of minimizing maternal risk while maintaining placental/fetal perfusion16 and to watch for exacerbation of HTN and progression to preeclampsia.17 Treatment options for HDP vary according to diagnosis, severity, gestational age, woman’s wishes, cultural and religious beliefs and the consultant’s recommendations. This chapter intends to provide a brief overview of possible management strategies for HDP. Management Strategies include: Assessment of HDP, Non pharmacological management stratégies, Pharmacological management strategies, Prevention strategies. Assessment of HDP: Includes: Investigations, Assessment of the risk for preeclampsia, Severity of preeclampsia, Presence of additional relevant findings, including identifiable causes of hypertension or kidney disease. Investigations: Hemoglobin levels: >13g/dL suggest hemoconcentration. Low levels suggest microangiopathic hemolysis or iron deficiency. Platelet count: <150,000/μL, suggest dilutional thrombocytopenia of pregnancy and preeclampsia. <100,000/μL, suggest preeclampsia or immune thrombocytopenic purpura(ITP). Prothrombin time(PT) and activated partial prothrombin time(aPTT): abnormal in consumptive coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy(DIC) complicating severe preeclampsia. Urinalysis: If >1+ proteinuria on dipstick, suggests need for 24 hour proteinuria. Blood urea and Serum creatinine: are reduced in uncomplicated pregnancy, “normal” values may indicate renal impairment. LFTs: transaminase concentrations increase in HELLP syndrome. Urate: rise in pre-eclampsia, largely due to reduced renal excretion. Clotting screen: when platelet count <100×109/l. Peripheral Blood film: microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia may occur in severe pre-eclampsia. Doppler Assessment of Uterine Arteries: Uterine artery dopplers are offered to high risk women between 20–24 weeks of pregnancy and have useful predictive power. Normal uterine Doppler at 20–24 weeks is considered low risk and abnormal dopplers suggest 20% chance of developing pre-eclampsia.18 MRI: MRI in preeclamptic women with severe visual disturbance, seizures or altered mental status is to evaluate cerebral edema, infarction or hemorrhage. An MRI is more sensitive than a CT scan for detecting cerebral cortical abnormalities but less useful in detecting cerebral hemorrhage. USG: Ultrasonography or CT scanning of liver is used to evaluate subcapsular hemorrhage or infarction in the setting of persistent severe right hypochondriac pain or markedly elevated hepatic transaminases. Fetal USG: HDP increases the risk of IUGR so regular fetal ultrasound scans is suggested to assess fetal growth, liquor volume and umbilical artery blood flow. Predictive Tests: A review of 27 different tests failed to identify a single biomarker or clinical factor that met the standards of clinical effectiveness typically applied to predictive tests. 19 At present, there is no single test that accurately predicts development of preeclampsia and further research on combine clinical and laboratory findings using multivariable models is ongoing. Assessment of the risk for preeclampsia: Early identification of women at risk is essential for prevention and for reducing the risk of preeclampsia-associated complications.20 21 Risk Factors: 22 23 Maternal risk factors for preeclampsia: First pregnancy. New partner/paternity. Age <18 years or >35 years. History of preeclampsia. Family history of preeclampsia in a first-degree relative. Black race. Obesity (BMI ≥30). Inter-pregnancy interval <2 or >10 years. Chronic HTN, especially secondary HTN (hypercortisolism, hyperaldosteronism, Pheochromocytoma, or renal artery stenosis). Preexisting diabetes (type 1 or type 2), especially with microvascular disease. Renal disease. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Thrombophilia. History of migraine. Use of selective serotonin uptake inhibitor antidepressants (SSRIs) beyond first trimester. Placental/fetal risk factors for preeclampsia: Multiple gestations. Hydrops fetalis. Gestational trophoblastic disease. Triploidy. Severity of preeclampsia: Consensus criteria for severity of preeclampsia include the presence of any one of the following: 13 Severe HTN (SBP ≥160mmHg or DBP ≥110mmHg, or both), New onset cerebral or visual disturbance, Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain, Oliguria, Progressive renal insufficiency (S Creatnine >1.1 mg/dl), Pulmonary edema, Cyanosis, Impaired liver function,(Twice the normal concentration), Thrombocytopenia,(<100000/micro liter), IUGR. Several guidelines include degree of proteinuria (3-5grams/day) and onset of preeclampsia prior to 34 weeks gestation in definition of severe preeclampsia. Presence of additional relevant findings, including identifiable causes of hypertension or kidney disease: Should be evaluated and treated accordingly. Non pharmacological management strategies: Preconception or Pre-pregnancy /initial visit counseling and evaluation: There is consensus across guidelines that preconception counseling should be provided to women with chronic (preexisting) HTN, regarding treatment strategies, medication risks and alternatives for those planning pregnancy. In women with chronic HTN, assessment before conception includes: Exclusion of secondary causes of HTN. Evaluation of their hypertensive control, Discussion of the increased risks of preeclampsia, Education about any drug alterations should they become pregnant. Poorly controlled HTN significantly increase maternal and fetal morbidity and mortality. Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) need to be withdrawn since they are fetotoxic. Women with history of poor obstetric outcomes or at high risk of preeclampsia be counseled for problem, self management, signs or symptoms of concern and offered preventive treatment options. Life Style Modification: A healthy lifestyle is generally recommended for pregnant women and guidelines recommend balanced nutrition for all pregnant women with special nutrition consultation for obese women. Calorie restriction for overweight or obese pregnant women is not recommended as it doers not decreased incidence of preeclampsia or gestational HTN and may contribute to starvation ketosis in fetus causing neuro-developmental problems. Guidelines for weight gain during pregnancy suggests a range of appropriate weight gain based on pre-pregnancy Body Mass Index(BMI).24 Salt Restriction: There is consensus across guidelines that salt restriction is not recommended solely to prevent gestational HTN or preeclampsia, since there is no clear evidence to support its effectiveness in high-risk women.12, 14 There is good evidence against recommending dietary salt restriction in low-risk women. Rest and Exercise: Physical activity is part of a healthy lifestyle and there is insufficient evidence to recommend rest or activity limitation for women with HDP. Guidelines identify preeclampsia and gestational HTN as absolute contraindications and poorly controlled chronic (preexisting) HTN as a relative contraindication to aerobic exercise in pregnancy. 25 WHO guidelines14 do not recommend rest at home for prevention of preeclampsia in women at risk. Besides other know benefits, lifestyle factors like abstention from alcohol and tobacco, do not have specific evidence for a reduction of the risk of preeclampsia. Changes in diet or bed rest have not been shown to provide maternal or fetal benefit. Most guidelines recommend against strict bed rest for inpatient care of women with HDP. Pharmacological management strategies: There is insufficient evidence to know which drug therapy is best, when to begin treatment, how vigorously to treat, or whether to stop treatment. The only trial for treatment of HTN during pregnancy with adequate infant follow-up (7.5 years) was performed over 30 years ago with alpha-methyldopa, now rarely used in nonpregnant patient. 26 27 While there is consensus on benefits of drug treatment of severe HTN in pregnancy, but the benefits are uncertain for treatment of mild to moderate HTN in pregnancy, either preexisting or pregnancy-induced, except for a lower risk of developing severe HTN.28 In the absence of RCTs, recommendations can only be guided by expert opinion. Non-acute management of HDP: Despite lack of evidence, the 2013 Task Force 13 reconfirms early initiation of antihypertensive treatment at values >140/90mmHg in HDP with methyldopa, labetalol and nifedipine. Betablockers (possibly causing foetal growth retardation if given in early pregnancy) and diuretics (reduction of plasma volume) should be used with caution. All antihypertensive drugs have been shown to cross the placenta and reach the fetal circulation, however, none of the antihypertensive agents in routine use have been documented to be teratogenic, but ACE inhibitors, ARBs and renin inhibitors are fetotoxic so should absolutely be avoided. In emergency (preeclampsia), intravenous labetalol is the drug of choice with sodium nitroprusside or nitroglycerin in intravenous infusion being the other option. Oral Antihypertensive Drugs: 16 29 Drugs Doses Methyldopa Standard dose: 250-1000 mg orally per day in 2-3 divided doses. Maximum dosage: 3000 mg/ day Standard dose: 200-800 mg orally per day in 2-3 divided doses Maximum dosage:2,400 mg/ day Standard dose: 30-60 mg orally per day Maximum dosage: 120 mg per day slowrelease preparation Adverse Effects Maternal sedation, elevated LFTs, depression, hemolytic anemia, Hydralazine 50-300 mg/day in 2-4 divided doses Headache, Should be avoided in women with cardiac conduction abnormalities, systolic heart failure or asthma. Headache, short acting nifedipine is not recommended due to the risk of hypotension. There is concern for severe hypotension if nifedipine is continued with intravenous magnesium. Should not be used as a sole agent due to reflex tachycardia; use with a beta-blocker Hydrochlorothiazide 12.5-50 mg/day but minimal benefit Can cause volume depletion and electrolyte Labetalol Nifedipine above 25 mg disorders; rarely initiated in pregnancy, but if patient taking prior to pregnancy may continue Acute management of HDP-severe HTN and preeclampsia: There is consensus across guidelines to acutely manage severe HTN with the goal of preventing maternal stroke and avoiding IUGR.16 Acute onset of persistent, severe HTN in pregnant or postpartum women with preeclampsia or eclampsia constitutes a hypertensive emergency.15 Management of severe HTN involves adequate BP control, often using parenteral agents and “expectant” management by trying to prolong the pregnancy without unduly risking the mother or fetus. Different units have their preferences for either parenteral hydralazine or labetalol and some use oral nifedipine. Hydralazine should be given after a colloid challenge to reduce the reflex tachycardia and abrupt hypotension, precipitated by vasodilatation of a volume contracted circulation. Rapidly BP control may lead to placental hypoperfusion, as placental blood flow is not autoregulated, and this will compromise the fetus. Across guidelines, inpatient care is recommended for women with severe HTN or preeclampsia and consideration of the rare home management for non-severe preeclampsia after initial inpatient care with recommendation of serial assessment of maternal and fetal condition. Guidelines uniformly recommend magnesium sulfate in severe preeclampsia to prevent seizures and for all women with preeclampsia who are in labor. But there is no definitive evidence for seizure prophylaxis in women with non-severe preeclampsia.16 Guidelines recommend admission to critical care for intensive monitoring and management for women with HDP and organ failure, severe pulmonary edema or sepsis, intractable HTN, anuria or renal failure, repeated seizure, massive blood loss with DIC, neurologic impairment requiring ventilation, or critical abdominal pathology. Pharmacologic Agents for Treatment of Severe Acute HTN:13 Drugs Doses Labetalol Nifedipine Hydralazine 20 mg IV, then 20-80 mg every 5-15 minutes, up to a max of 300 mg or constant infusion of 1-2mg/min 10-30 mg PO (NOT sublingual), repeat in 45 minutes if needed 5 mg IV or IM, then 5-10 mg every 20-40 minutes IV or continuous infusion of 0.5-10 mg/h Adverse Effects Maternal tachycardia and arrhythmia Only used in absence of parenteral options Maternal hypotension, fetal bradycardia; maternal tachycardia often dose-limiting side effect Management of Eclampsia: Magnesium sulfate is first line treatment for seizures in eclampsia. Guidelinerecommend 4-6 grams in 100cc IV infusion in 15 minutes, followed by 1-2 grams IV infusion per hour. BP, respiratory rate, urine output and deep tendon reflexes should be monitored during magnesium sulfate administration. Repeat boluses of 2-4 grams can be administered for recurrent seizures. Other agents are considered only if magnesium sulfate is ineffective or contraindicated and include phenytoin and benzodiazepines. Delivery timing in eclampsia: Considerations for delivery timing in eclampsia include assessment of stability with regard to BP, urinary output and fetal heart rate. A consensus recommendation is delivery two hours after stability is achieved. Therapy for HELLP syndrome: Transfusion therapy: Based on expert consensus12 of risk of profound hemorrhage, platelet transfusion is recommended prior to vaginal delivery or cesarean section for any woman with HELLP syndrome with platelet count of <50x109/L and falling and/or there is coagulopathy and some experts recommend platelet transfusion for platelet count <40x109/L prior to intubation for cesarean section. 30 Prophylactic platelet transfusion is not recommended, even prior to cesarean delivery, if platelet count is >50x109/L and there is no excessive bleeding or evidence of platelet dysfunction.12 Other therapy for HELLP syndrome: The use of corticosteroids for HELLP syndrome is not well defined in the literature. Only SOGC guidelines12 recommend corticosteroids with platelet counts <50x109/L, other guidelines, including those of the WHO14, do not recommend the use of corticosteroids in HELLP syndrome. SOGC guidelines note insufficient evidence for plasma exchange or plasmapheresis, noting that observational studies have suggested improved hematological and biochemical indicators, but small RCTs have found no maternal or perinatal outcome improvement. Thromboprophylaxis: Recommendations for thromboprophylaxis differ among guidelines. Guidelines 31 32 33.34 recommend assessment of risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and antenatal prophylaxis with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) as early in pregnancy as possible for women at risk. Preeclampsia is a risk factor for thrombosis, particularly in presence of additional risk factors such as obesity, >35 years, previous thrombotic event, family history of thrombosis, nephrotic range proteinuria or likely inpatient stay more than a few days, other risk factors include previous recurrent VTE, previous unprovoked or estrogen or pregnancy-related VTE, previous VTE and a history of VTE in a first degree relative or documented thrombophilia. Guidelines consider compression stockings for hospitalized women and postpartum thromboprophylaxis for women with preeclampsia unless it is contraindicated. Post partum LMWH should not be administered until two hours after epidural catheter removal. When women are admitted for observation in hospital they will usually be relatively immobile and graduated compression stockings should be considered, with or without prophylactic LMWH. Postpartum evaluation/surveillance and management:16 HDP may resolve immediately following delivery, or can persist for several weeks or months. HTN and/or preeclampsia can also arise for the first time (de novo) in postpartum period after a normotensive pregnancy. Optimal management of postpartum HTN is not well understood,35 36 that is why close monitoring is essential in postpartum period. Post partum HTN is common and BP typically rises after delivery over first five days37 so BP is monitored immediately after the birth, daily for the first 2 days and at least once between day 3 and day 5 after birth. Initiate antihypertensive treatment if BP is > 140/90 mmHg.2 WHO guidelines14 recommend continuing antihypertensive treatment postpartum in women treated antenatally. Women who are breastfeeding should be offered information regarding antihypertensive agents. Guidelines note that all antihypertensive medications are believed to be compatible with breastfeeding, but using medications with a well-established record is reasonable, as the safety data for doxazosin, amlodipine and ARBs are lacking. Although available data suggest that all studied agents are excreted into human breast milk, but most are excreted to a negligible degree. The JNC15recommends against ACE/ARB therapy based on reports of adverse fetal and neonatal effects and insufficient evidence of safety. Diuretics can decrease lactation and with methyldopa there is risk of postnatal depression so both should be avoided. Postpartum surveillance should include confirmation of resolution of end-organ dysfunction, monitoring platelet count, transaminases and serum creatinine in the 48-72 hours after birth for women with preeclampsia, to be repeated as clinically indicated. Derangement should resolve at 6 weeks post partum. If proteinuria does not remit by three months post partum, further renal investigations are required. Recurrence of Hypertension in Subsequent Pregnancy: HTN recurs in 20-50% of subsequent pregnancies in women with HDP, particularly in early onset HDP, a history of chronic (preexisting) HTN, or HTN persisting beyond 5 weeks postpartum.38 The risk of developing HTN is almost four-fold.39 Data from 5 cohort studies suggests that women who have had gestational HTN have a 32% risk of developing gestational HTN and 3% chance of developing preeclampsia in a subsequent pregnancy. Women with preeclampsia in previous pregnancy have a 38.5% risk of developing gestational HTN and a 14.5% chance of developing preeclampsia in a subsequent pregnancy (based on 8 retrospective cohort studies).2 In addition, severe isolated IUGR is also a risk factor for developing HTN in a subsequent pregnancy HDP & cardiovascular consequences: Hypertensive disorders have been recognized as an important risk factor for CVD in women and women with preeclampsia have nearly a 2 fold increase in risk for ischemic heart disease (IHD), stroke and VTE in 5 to 15 years after the pregnancy.40 Two large reviews suggest women who develop preeclampsia experience an increased lifetime risk of HTN, cerebrovascular and cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, renal disease and thromboembolism.41 42 Because of its CV and metabolic stress, pregnancy provides a unique opportunity to estimate a woman’s lifetime risk, a window into the future CV health of women, which is unavailable in men. Interestingly, women who go through a pregnancy without developing HTN are at a reduced risk of becoming hypertensive in later life, when compared to nulliparous women. Timing of birth: Determination of delivery timing in women with HDP is a complex decision that requires consideration of gestational age, degree of BP control and patterns of maternal and fetal adverse conditions such as HELLP syndrome, deteriorating renal function and fetal distress or IUGR.2 Do not offer birth before 37 weeks to women with HDP whose BP is <160/110mmHg, with or without antihypertensive treatment. Manage pregnancy in women with pre-eclampsia conservatively until 34 weeks and offer birth to women if: severe HTN develops refractory to treatment or maternal or fetal indications develop. Recommend birth within 24–48 hours for women who have pre-eclampsia with mild or moderate HTN after 37 weeks. Seizure prophylaxis: Guidelines uniformly recommend magnesium sulfate in severe preeclampsia to prevent seizures and should be considered for all women in labor with preeclampsia. There is no definitive evidence for seizure prophylaxis in women with non-severe preeclampsia. WHO guidelines14 recommend a full regimen of magnesium sulfate for prevention as well as treatment. Prevention strategies: Risk reduction for preeclampsia and other complications of HDP: Aspirin: There is general consensus across guidelines including those of WHO, that women at high risk for preeclampsia should receive low-dose aspirin (75 mg/day) that too as early as possible for maximal benefit and should continue to delivery.14 WHO14 recommends initiation prior to 20 weeks gestation. More evidence is needed to ascertain benefit of low-dose aspirin therapy for women with mild to moderate risk factors for preeclampsia. Other pharmaceuticals: Other than low-dose aspirin, there are no pharmaceuticals recommended in current guidelines for the prevention of preeclampsia or its complications. Antihypertensive therapy specifically to prevent preeclampsia is not recommended. There is insufficient evidence to recommend LMWH for preventing preeclampsia, even in thrombophilia or previous preeclampsia. Nitric oxide donors, diuretics and progesterone are not recommended in guidelines14 for the prevention of preeclampsia or its complications. Dietary calcium supplementation: There is no clear evidence for the benefit of calcium for the reduction of the risk of preeclampsia. The greatest effect of calcium supplementation has been shown in high-risk women with poor intake and has included a small decrease in the incidence of preeclampsia, and also a decrease in maternal death and serious morbidity.12 WHO guidelines14 recommend supplementation with 1.5-2 grams elemental calcium per day for pregnant women, particularly those at high risk for preeclampsia, in areas where dietary calcium intake is low. Other dietary supplements: There is no evidence for the benefit of magnesium, vitamin C and E and prostaglandin precursors such as fish oils or algal oils. There is insufficient evidence to recommend garlic, zinc, pyridoxine or selenium. WHO guidelines14 do not recommend Vitamin D supplementation for the prevention of preeclampsia and its complications. There is poor evidence for the use of folic acid in the prevention of HDP. Summary: HDP is a unique clinical condition comprised of a spectrum of disorders typically classified into 4 categories and has major short-term and long-term antenatal, perinatal and postpartum implications for both mother and fetus. The goal of management strategies in HDP is to optimize pregnancy outcome, minimizing maternal risk while maintaining placental/fetal perfusion and prevent exacerbation of HTN and progression to preeclampsia. Treatment options for HDP vary according to diagnosis, severity, gestational age, woman’s wishes, cultural and religious beliefs and the consultant’s recommendations. HDP serves as a window of opportunity to predict future CV risk- something not possible in nulliparous women. While there is consensus on benefits of drug treatment of severe HTN in pregnancy, but the benefits are uncertain for treatment of mild to moderate HTN in pregnancy. Availability of only a limited number of antihypertensive drugs that have documented safety and efficacy in pregnancy makes the task even more challenging. References: 1 Chesley LC. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. New York, NY: Appleton-Century-Crofts; 1978. Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) Clinical Guideline- Hypertension in Pregnancy: the Management of Hypertensive Disorders during Pregnancy. August 2010. http://publications.nice.org.uk/ hypertension-in-pregnancy-cg107 Accessed December 10, 2012. 3 Berg CJ, Callaghan WM, Syverson C, Henderson Z. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States 1998-2005. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2010; 116(6): 1302-1309. 4 Roberts JM, Pearson G, Cutler J, Lindheimer M. Summary of the NHLBI Working Group on Research on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Hypertension 2003; 41:437-445. 5 Rahul Mehrotra, Manish Bansal, Ravinder s. Sambi, Krishna C. K. Hypertension in pregnancy: Challenges and solutions. Indian Heart J. 2010; 62:423-426 6 Ness RB, Roberts JM. Epidemiology of hypertension. In: Lindheimer MD, Roberts JM, Cunningham FG, editors. Chesley’s Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy, 2nd ed. Stamford, Connecticut: Appleton & Lange, 1999: 43–65. (3rd edition revision in press, May 2009, Elsevier). 7 Villar J, Say L, Gulmezoglu AM, Marialdi M, Lindheimer MD, Betran AP, et al. Pre-eclampsia eclampsia: a health problem for 2000 years. In: Critchly H, MacLean A, Poston L, Walker J, editors. Pre-eclampsia. London, England: RCOG Press, 2003: 189–207. 8 Gross CP, Anderson CF, Rowe NR. The relation between funding by the National Institutes of Health and the burden of disease. N Engl J Med 1999; 340: 1881–7. 9 National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group report on high blood pressure in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1990; 163:1691-1712. 10 Davey DA, MacGillivray I. The classification and definition of the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988;158:892-898 11 2013 ESH/ESC Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Journal of Hypertension 2013, 31:1281–1357 12 Magee LA, Helewa M, Moutquin J-M et al. Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC). Clinical Practice Guideline- Diagnosis, Evaluation and Management of the Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008; 30 (3, Supplement 1): S1-S48. 13 Executive Summary, Hypertension in Pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstetrics & Gynecology. Vol. 122, No. 5, November 2013 14 World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for prevention and treatment of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. WHO Press, Geneva, Switzerland. 2011. http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/maternal_perinatal _health/rhr_11_30/en/index.html Accessed December 10, 2012. 15 National High Blood Pressure Education Program, National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health. NIH Publication No. 04-5230. August 2004. http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.htm Accessed December 10, 2012. 16 Hypertensive Disorders in Pregnancy. Guideline Summary, New York State Department of Health. May 2013 2 17 Sibai BM. Diagnosis and management of gestational hypertension and preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2003 Jul; 102(1):181-192. 18 Smith GCS, Pell JP, Walsh D. Pregnancy complications and maternal complications of ischaemic heart disease: a retrospective cohort study of 129 290 births. Lancet 2001; 357:2002–6. 19 Meads CA, Cnossen JS, Meher S, Juarez-Garcia A, ter Riet G, Duley L, et al. Methods of prediction and prevention of pre-eclampsia: systematic reviews of accuracy and effectiveness literature with economic modeling. Health Technol Assess 2008 Mar; 12(6): iii-iv, 1-270. 20 Turner JA. Int J Womens Health 2010; 2. 21 Report of the National High Blood Pressure Education Program Working Group on High Blood Pressure in Pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2000; 183(1):S1-S22. 22 Nelson-Piercy C. Handbook of Obstetric Medicine. 3rd ed: Informa Health Care; 2007. 23 Duckitt K, Harrington D. Risk factors for pre-eclampsia at antenatal booking: systematic review of controlled studies. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.). 2005; 330(7491):565. 24 IOM (Institute of Medicine) and NRC (National Research Council). 2009. Washington, DC: the National Academies Press. 25 Committee on Obstetric Practice. ACOG committee opinion. Exercise during pregnancy and the postpartum period. Number 267, January 2002. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Int J Gynecol Obstet 2002; 77(1):7981. 26 Redman CW. Fetal outcome in trial of antihypertensive treatment in pregnancy. Lancet. 1976; 2: 753–756. 27 Cockburn J, Moar VA, Ounsted M, Redman CW. Final report of study on hypertension during pregnancy: the effects of specific treatment on the growth and development of the children. Lancet. 1982; 1: 647–649. 28 Abalos E, Duley L, Steyn DW, Henderson-Smart DJ. Antihypertensive drug therapy for mild to moderate hypertension during pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2001; CD002252. 29 American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Chronic hypertension in Pregnancy. Practice Bulletin number 125. Obstetrics and Gynecology 2012; 119 (2 Part 1): 396-407. 30 Sibai BM. Diagnosis, controversies and management of the syndrome of hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelet count. Obstet Gynecol 2004; 103:981-991. 31 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists/ American Academy of Pediatrics (ACOG/AAP). Guidelines for Perinatal Care Sixth Edition 2007. 32 Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. Reducing the risk of thrombosis and embolism during pregnancy and the puerperium. Green top guideline #37a. November, 2009. http://www.rcog.org.uk/files/rcogcorp/GTG37aReducingRiskThrombosis.pdf Accessed December 10, 2012. 33 Society of Obstetric Medicine of Australia and New Zealand (SOMANZ). Guidelines for the Management of Hypertensive Disorders of Pregnancy. 2008. 34 Hague WM, North RA, Gallus AS, Walters BN et al. Anticoagulation in pregnancy and the puerperium. Med J Aust. 2001; 175:258-63. 35 Magee L, Sadeghi S. Prevention and treatment of postpartum hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005 Jan 25;(1)(1): CD004351 36 Sibai BM. Etiology and management of postpartum hypertension-preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011 Sep 16. 37 Sibai BM. Treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1996; 335:257–65. 38 ACOG Committee on Practice bulletins--Obstetrics. Diagnosis and Management of Preeclampsia and Eclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 2002; 99(1):159-67. 39 McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J 2008; 156:918–930. 40 Mosca L, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bezanson JL, Dolor RJ, Lloyd-Jones DM, et al. Effectiveness-based guidelines for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in women: 2011 update: aguideline from the American Heart Association. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011; 57:1404–1423. 41 Bellamy L, Casas JP, Hingorani AD, Williams DJ. Pre-eclampsia and risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer in later life: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ 2007 Nov 10; 335(7627):974. 42 McDonald SD, Malinowski A, Zhou Q, Yusuf S, Devereaux PJ. Cardiovascular sequelae of preeclampsia/eclampsia: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Am Heart J 2008 Nov;156(5):918-930