* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Quality Imperative: Lessons from the Cath Lab

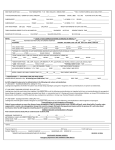

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

The Quality Imperative: Lessons from the Cath Lab Protecting Patients, Meeting Reform Goals and Assessing Performance with Accuracy and Fairness The Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) October XX, 2010 T he recently enacted health care reform legislation promises profound change for our health care system. Officially known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), its main goal is to expand access to an additional 32 million Americans. PPACA also suggests the system is marred by escalating costs without a corresponding rise in quality. As a result, the act attempts to cut costs without compromising care through a variety of means, including payment reform, delivery of care reform, provider reimbursement reductions, and quality improvements that deliver better care at lower costs. As physicians closely involved in the current health care system, we agree systemic changes are essential to achieve the goals of the PPACA. But we believe it is essential to safeguard quality of care so Americans can continue to have faith that their physicians are first and foremost concerned about their medical care. It’s clear that policymakers believe reimbursement ...we believe it is essential to strategies can improve safeguard quality of care so health care quality and outcomes and reduce Americans can continue to costs. This “pay-forhave faith that their physicians performance” (P4P) focus are first and foremost concerned is manifest throughout the legislation in elements about their medical care. such as the new “Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation,” the “Medicare Shared Savings Program”, the “Hospital Value Based Purchasing Program” and multiple pilot programs, all designed to “improve quality” and “test, evaluate, and expand in Medicare, Medicaid and CHIP (Children’s Health Insurance Program) different payment structures and methodologies to reduce program expenditures...” 1 Integral to these P4P programs is the belief that quality can be measured, tracked, and improved, and that payment reform models based on quality will 2 not only deliver better care, they will “reduce the rate of cost growth.” The clock is ticking, however, as recommendations for a “national quality strategy” that includes processes to develop quality measures is due by Jan. 1, 2011; by 2012, PPACA will initiate other changes, including a program to share cost savings, a reduction in Medicare payments for “excess (preventable) hospital readmissions” and “a hospital value-based purchasing program” for Medicare.2 We share policymakers’ sense of urgency around quality improvement as well as their belief that quality can be improved, and used, potentially, as a means to incentivize better performance. Done well, quality improvement programs in the hospital setting improve patient outcomes and value to the health care system by: • Driving new and better means to enhance care; • Showing which interventions work and which do not; • Identifying specific areas in need of improvement and targets for future research; • Pinpointing specific systems, operators or facilities with less than optimal outcomes or problems that require remediation; • Developing and supporting remediation through corrective action planning to ensure patient safety and preserve important health care resources; and • Reducing preventable complications and hospital-acquired conditions. Done poorly, however, quality improvement efforts can wreak havoc within the health care system and compromise access to and quality of patient care. Scarce resources can be wasted if ineffective quality of care programs “crowd out” outcomes-based quality improvement efforts. Worse, proponents of effective quality improvement can be alienated, discouraged or even intimidated by a poorly run process, resulting in lackluster support for quality improvement efforts. Most troubling, though, is that patient care could suffer if highly skilled physicians are penalized simply because they took on the toughest cases. It’s a rare but feasible possibility that the ill-defined quality improvement program could result in physicians “cherry picking” the easier cases – and avoiding the more complex ones – as a means of safeguarding their performance. This unintended consequence of measuring performance without adjusting for the patient’s condition is to reduce access for the sickest patients because they represent the highest risk. Ironically, such a poorly-defined quality improvement program would also undermine a candid and objective assessment of care delivery processes and systems, operator effectiveness, and patient outcomes. Given the complexity of quality improvement programs, it is all too possible to unintentionally create a program that would hamper quality improvement rather than promote it. Our health care system cannot afford the serious distractions and repercussions that would result from this kind of failure –and our patients certainly deserve more. We are eager to work with policymakers and other health care stakeholders to ensure that quality improvement programs: • Focus on outcome measures (did the individual patient do as well or better than expected, based on his or her health status?) as well as process measures (did the physician and/or operator follow evidenced-based guidelines appropriate for the situation?); • Rely on accurate and verified clinical data, subject to random audits by competent and objective reviewers -- not administrative claims data that are designed for billing purposes; • Use data that is risk adjusted to reflect the individual patient’s health and condition; • Benchmark against a national standard so that observed outcomes versus expected results can be tracked and evaluated; and • Are dedicated to a continuous quality improvement approach that seeks to improve patient outcomes, not just show adherence to protocols. While quality improvement as a discipline is still in its infancy, there are a number of programs in existence today that can guide policymakers as they move to implement the PPACA requirement to develop its “national quality strategy” and its processes for quality measures. By the start of next year, PPACA requires the development of “a national quality improvement strategy that includes priorities to improve the delivery of health care services, patient health outcomes, and population health.” This paper seeks to explore the essential components of an effective quality improvement program, pitfalls to anticipate and guard against, and issues that policymakers should consider in the delivery of the quality strategy recommendation. Given the complexity of quality improvement programs, it is all too possible to unintentionally create a program that would hamper quality improvement rather than promote it. Our health care system cannot afford the serious distractions and repercussions that would result from this kind of failure –and our patients certainly deserve more. 3 The Urgent Need for Quality Improvement – and the Pitfalls of Doing it Wrong Consider this fact: Before the first angioplasty procedure more than 30 years ago, if you had a heart attack, you had a one in four chance of dying; today, more than 95 percent of heart attack victims who arrive at the hospital for treatment survive. Starting with the introduction of angioplasty, there have been a series of scientific innovations and medical breakthroughs in cardiovascular medicine, including stents, that have enhanced benefits and reduced risks for heart patients. Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) procedures involve threading a slender tube into the arteries of the heart, expanding a tiny balloon to widen the artery and, usually, leaving an expandable metal stent in place to hold the artery open. As a result, interventional cardiologists are able to stop heart attacks, prevent strokes, correct congenital heart problems and improve quality of life, and have done so for millions of heart disease patients. Although “quality improvement” is often associated with these significant scientific advances, continuous quality improvement (CQI) describes an organized, scientific process for evaluating, planning, improving and reassessing quality.3 The end goal is to deliver the right care at the right time to the right patient by following best practices procedure by procedure, providing timely care patient by patient, and striving, physician by physician, to avoid unnecessary tests and procedures, medical errors and complications. The question is: how can quality be accurately measured, especially at the ground level of individual cath labs and interventional cardiologists? There have been many attempts to answer this question; most, for one reason or another, have fallen short. 4 Public assessments of a hospital’s quality often rely on testimonials, rankings or self-proclaimed “centers of excellence” designations. What may be heart-warming and inspiring tributes are clearly not objective, validated indications of quality. Likewise, published hospital rankings and health grades have, at best, a tenuous correlation with improved outcomes, according to peer-reviewed studies. 4 5 6 A key obstacle to measuring quality is that most of the available measuring sticks have flaws. For instance, administrative data are often used to measure quality because they are accessible and inexpensive. But assessing quality based on information from insurance claims or billing statements – designed for accountants, not clinicians – is simply inadequate for the purposes of scientific inquiry. Nevertheless, many existing report cards and rating systems depend on administrative data. Attempts to “risk-adjust” those data have been shown to be highly inconsistent.7 This has brought considerable danger to the publication of data on individual physicians, especially if it is used to rate performance in a P4P reimbursement model. Many physicians will become unduly discouraged by this unfair evaluation of their performance, and, as previously noted, may avoid taking on the most complex cases. Meanwhile, some may be tempted to focus on “gaming the system” as a means to improve their performance scores. Clearly, such report cards or rating systems will provide a disincentive to physicians when it comes to taking on patients with severe or costly conditions. For instance, after the New York State Department of Health Cardiac Surgery Reporting System began making public disclosure of individual surgeons’ mortality rates following coronary artery bypass, researchers sent 150 New York State cardiac surgeons an anonymous mail survey in 1997. Of the 104 respondents, 62% refused to operate on at least one high-risk patient within the last 12 months due to public reporting.8 ...researchers found that report cards in New York and Pennsylvania led to higher Medicare expenditures and adverse outcomes relative to nearby states that did not have similar report cards. Corroborating this survey are studies showing this public reporting of cardiac surgery outcomes in New York – and Pennsylvania, which also had a coronary artery bypass surgery report card – resulted in an increasing number of high-risk patients being referred out of state.9 10 In addition, not only did the illness severity of patients receiving the surgery decline in Pennsylvania and New York compared to states without report cards, there were more surgeries performed on healthier patients.11 And consistent with increased sorting of patients related to report cards were delays in treatment for both healthy and sick patients due to time required for the sorting process. Finally, researchers found that report cards in New York and Pennsylvania led to higher Medicare expenditures and adverse outcomes relative to nearby states that did not have similar report cards.12 In addition, physicians fear that such flawed reporting systems may end up misleading patients, misdirecting them at a time of critical decision making about their health.13 For instance, last year, a national newspaper cited an analysis of Medicare data to conclude that Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston had a death rate among angioplasty patients that was twice the state’s rate.14 Although the story included the fact that an independent audit showed most of the deaths resulted from the hospital’s willingness to treat patients with a slim chance of survival, one may rightly wonder how many heart patients or their families balked at going to Massachusetts General because of that story. Likewise, process measures, which assess the activities performed when health care professionals provide care to patients (physical exams, diagnostic testing, staffing ratios, etc), ignore critical elements to providing optimal patient care, such as the physician’s clinical judgment and the patient’s overall health condition. In fact, recent studies show a lack of correlation between most process measures and risk-adjusted outcomes.15 16 Clearly, there are some guidelines and best practices, such as giving aspirin to heart attack patients or shortening the so-called “door-to-balloon” time for those patients, that play an important role in improving quality; but most outcomes have many associated processes associated and perfecting any one – or even a few – of them may not result in measurable improvement in outcomes. There is also concern that quality improvement programs that do not see improving quality as a continuous process may stifle innovation. Linking performance measurement and reimbursement to an existing standard will, by its nature, encourage the status quo. Such programs encourage compliance to the detriment of the patient. Likewise, there is the danger that aggressive treatment may be deemed “inappropriate use” despite the circumstances of the procedure and the condition of the patient. In the end, we must avoid quality improvement programs that put a chilling effect on innovation – after all, it is innovation that has repeatedly been proven to improve care, save lives, and advance the quality of medical care. Fortunately, there are outcomes-based quality programs that use risk-adjusted information gathered by trained clinicians from medical charts to create a prospective, peer-controlled, validated database that takes into consideration the patient’s condition in assessing outcomes and can help pinpoint a program’s specific strengths and weaknesses. They provide a continuous process of measuring performance and providing feedback to the clinician, which numerous studies have found lead to improvements in performance.17 5 In Michigan, for instance, a statewide CQI initiative for cath labs showed demonstrable decreases in bleeding,18 transfusion requirements, vascular complications, and a reduction in contrast nephropathy. Likewise, peer-reviewed studies have shown that a surgical quality improvement program is effective in improving the quality of surgical care and in reducing complications. Higher quality and lower rates of complications translate into lower costs – a not insignificant by-product, given that health care costs continue to escalate at a time when we are increasingly strapped for resources. Given the current interest from policymakers to develop a national quality improvement strategy and use P4P programs to improve quality and outcomes and reduce costs, it is important to understand what tools and programs have shown effectiveness in measuring, tracking and improving quality. Consider the robust quality improvement model developed for cath labs and interventional cardiologists by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) and implemented in tandem with the American College of Cardiology’s (ACC) National Cardiovascular Data Registry (NCDR). While it is a work in progress, as any continuous quality improvement program should be, its scientific rigor and validity is earning the respect of clinicians worldwide. The Elements of a Continuous Quality Improvement (CQI) Program in the Cath Lab Improving quality in cath labs means routinely striving to protect patient safety, improve outcomes and carefully weigh the risks of the procedure against the condition of the patient. This approach continuously strives to enhance processes, efficiencies and outcomes based on a fair physician-led review of performance that objectively evaluates structure, process and outcomes and takes the appropriate corrective action when necessary. 6 That’s why we recommended CQI for all cath labs in the 2005 PCI guideline update from the SCAI, ACC and the American Heart Association (AHA);19 in addition, we required CQI as a part of the new Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence (ACE) program from SCAI and ACC.20 ACE will offer objective, peer-review evaluation of processes and assessment of outcomes based on established benchmarks, tools and guidance for improvement, and when necessary, help in developing corrective action plans. For cath labs, SCAI recommends five key elements as part of a CQI program “blueprint”: • Collecting data; • Benchmarking data to find where improvement is needed; • Identifying quality indicators; • Correcting deficiencies; and • Reassessing the data to gauge the effect of the corrective action. A fundamental element for a CQI program, according to SCAI, is to prospectively gather data about all of a cath lab’s procedures and compare the outcomes to national norms. To create those national norms, SCAI encourages all interventional cardiologists and cath labs to send their PCI data to the NCDR CathPCI Registry. Registry data, which collect patient demographics, clinical variables, and outcomes on each procedure, are used to provide quarterly reports with benchmarking and risk-adjusted outcomes. The NCDR is the most comprehensive outcomes-based quality improvement program in the U.S. with a suite of data registries involving more than 2,400 hospitals and more than 10.6 million patient records.21 The evidence-based data are combined with process and performance measures linked to current ACC/AHA/ SCAI clinical practice guidelines.22 To implement CQI, an independent committee should be created with oversight over all aspects of the CQI process to establish quality indicators, track performance, and identify and correct problems. Often directed by the cath lab director, SCAI suggests the committee include among its other voting members interventional cardiologists and others associated with the cath labs as well as non-interventional cardiologists, cardiac surgeons, emergency room physicians and non-cardiologist internists. Non-voting members may include representatives of the hospital’s quality assurance and cardiovascular administrations. While protecting patient safety is the primary purpose of the CQI committee, identifying deficiencies in the program must be done openly and with the involvement, as appropriate, of the hospital’s risk management staff. The committee must operate with equity and transparency to ensure fairness to operators whose work they will review, quality for the patient and credibility for the process. One of the first tasks of the committee is to identify quality indicators based on guidelines, accreditation bodies, and local practice requirements. These indicators often apply to processes and outcomes within the cath lab, but may also include outside factors affecting cath lab quality. For instance, in a patient undergoing a heart attack, an important quality indicator is how long it takes for the patient to receive angioplasty after entering the Emergency Room – the “door-to-balloon” time. The committee regularly uses these quality indicators to evaluate the cath lab’s performance. Clinical practice guidelines and appropriateness criteria are an essential part of the CQI process. While guidelines are intended only as suggestions based on scientific studies and cannot replace the clinical judgment of the physician, it has been shown that when overall guidelines are followed, clinical outcomes improve.23 In 2009, several professional organizations, including the ACC, SCAI, STS and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery (AATS), conducted an “appropriateness review” of common clinical scenarios in which PCI is a possible treatment. These scenarios included information on symptom status, extent of medical therapy, risk level as assessed by noninvasive testing, and coronary anatomy. About 180 clinical scenarios were developed and scored on a scale of 1 to 9. Scores of 7 to 9 indicate that PCI was considered appropriate for the patient and likely to improve health outcomes or survival; often, these patients had heart attack, significant heart disease symptoms and/or chest pain.24 In contrast, scores of 1 to 3 indicate PCI was considered inappropriate for the patient and unlikely to improve health outcomes or survival; typically, these patients did not have symptoms or were found to be of lowrisk by a noninvasive test. This appropriateness rating system is expected to guide physician decision making, patient education and future research. While a cath lab does not have the workforce to assess the appropriateness of each procedure, random case reviews should evaluate appropriateness, procedure documentation and technique. Such reviews may identify cases in which the operator prescribes PCI for low risk patients who should have been treated only with medication. Operators who frequently conflict with guidelines or appropriateness criteria may prompt the CQI committee to require a peer assessment of performance. We should not equate quality with lack of complications, for to do so is to penalize physicians who take on complex procedures and high-risk patients. 7 Data Collection and Benchmarking Peer Review and Remediation When a cath lab’s data vary significantly from quality indicators, appropriateness criteria or from national or regional norms, an internal peer-review process should examine patient selection and outcomes. Just as good drivers learn from “fender benders,” good physicians learn from procedures that result in complications. Sometimes, fender benders are due to poor weather conditions, mechanical failure, traffic, other drivers or operator error. Other times, a pattern of fender benders suggests the driver is not anticipating or responding to changing conditions, is impaired or inattentive, or has some other issue that needs remediation. Likewise, just as we need to go beyond traffic reports to assess the quality of a driver, we need to go beyond complication rates to assess the quality of the physician. Benchmarking against national standards enables reviewers to compare an individual cath lab’s outcomes to expected results as determined by national registry data, which has been shown to be effective in predicting outcomes. By comparing a cath lab’s data to national benchmarks, reviewers can detect worrisome patterns. For instance, benchmarking may detect a higher-than-average proportion of the cath lab’s patients received PCI even though they may not have been deemed an appropriate candidate based on their condition. At the same time, it is critical to understand when a pattern is “worrisome” as opposed to when it reflects a much more difficult and complex patient base. We should not equate quality with lack of complications, for to do so is to penalize physicians who take on complex procedures and high-risk patients. This could deny access to such patients as the 65-year-old patient who has already had two coronary bypass surgeries and now is in need of a third or another procedure; many heart surgeons or interventionalists would not take on such a high-risk patient, especially if a less than optimal outcome would damage their professional reputation. This is why it is so critical to be sure that the data is riskadjusted so that the comparisons are fair, accurate and relevant. That’s why all outcomes should be adjusted to reflect the risk of the patient’s condition as part of the process of determining if the procedure was appropriate for that patient. 8 Evaluating an individual operator’s “quality” is an integral part of a cath lab’s CQI process. The clinical proficiency of each operator should be the subject of an ongoing peer-review assessment that includes random case review, identifies strengths and weaknesses of the cath lab and the individual operator, and compares individual and cath lab outcomes against national standards and benchmark databases. While operators may aspire to a high standard of performance, they must also be required to meet minimum standards to maintain their privileges to operate in the cath lab.25 Once again, this peer-review process should be seen as much about learning as it is about remediation. The CQI committee and the hospital’s quality management department need to work closely together to investigate reported events. Yet there are many challenges to applying the CQI and peer-review processes in a constructive and impartial manner. For instance, close attention should be paid to avoiding conflicts of interest in which the peer reviewer may benefit from adjudicating adversely on a physician’s care for political, financial or personal reasons. Unfortunately, there have been cases, albeit rare, in which physicians were unfairly sanctioned.26 For example, complications can occur in any circumstance, such as damage to an artery during angioplasty; or unforeseen problems may be discovered during a procedure. Peer reviewers must strive to consider the context in which the procedure was performed, and not judge a physician harshly simply because the outcome did not measure up to national norms. Conversely, reviewers must not close ranks and protect physicians who are falling short of expectations and are possibly in need of remediation or sanction. Concerns with operator performance may relate to professional behavior, such as poor attitude or ethical conduct; inadequacies in knowledge, judgment or procedural skills; mental impairment or addictive substance abuse; or a combination of any of the above. To assure credibility, the peer-review process must remain impartial, consistently applying review criteria and establishing a random review mechanism to avoid enabling operators to “game” the system. Remediation often starts with a “neutral,” wellrespected individual in the cath lab assigned to discuss the quality issue with the operator in question using benchmarking data. Often this quiet, though legally protected, discussion may be enough to solve the performance problem. This process, as defined in federal law, requires due process, protects confidentiality and shields participants from litigation.27 This is important, since if they are not protected, these conversations and remediation may be perceived as punitive; that may, in turn, be an obstacle to the conversation and remediation, thereby stifling quality improvement. When further education or training is called for, it is typically part of a non-punitive action plan that specifies the required changes and includes appropriate, constructive feedback. This corrective action plan should include effectiveness measurements and clearly state expected outcomes or targets. Corrective actions should be reassessed on an ongoing basis, and may prompt further steps, such as additional education or mentoring. When an internal resolution cannot be reached, the case should be referred to the proper review body within or outside the institution. Outside reviewers should be impartial experts whose selection is subject to the approval of all relevant parties. A formal peer review of an individual physician’s professional competence may or may not result in punitive actions, such as suspension or revocation of privileges, depending on the findings of the review. Thoughtful consideration and clear deliberation on physician remediation must be factored and weighted against physician punishment. Since our society has heavily invested in and depends on the skills of our physicians, every effort should be made to resolve quality problems through remediation. This is especially true at a time when the physician supply is already stressed due to a decreasing number of physicians ready to replace those who are retiring and rising demand for medical services due to our aging population. Assessment and remediation programs – such as the Physician Assessment and Clinical Education Program at the University of California, San Diego – can make a difference by sorting out those physicians who are fully competent from those who are not, and between those who could benefit from additional training and those who should no longer be practicing medicine.28 CQI must, by definition, identify program elements, processes and operators in need of improvement. If it is portrayed or viewed primarily as a way to identify, investigate and punish outliers in the cath lab, its ability to effect quality improvement in the cath lab will be undermined because it likely will deter medical and hospital personnel from raising problems. 9 Conclusion and Recommendations There is a robust CQI process available for cath labs, and while it is not perfect, it is the best there is for delivering clear, measurable results. Improving quality is ever a work in progress, and the interventional cardiology community continues to seek improvement and collaborate with other specialties, such as anesthesiology and surgery. However, spurred by health care reform and increased payer and policymaker interest in quality and cost, cath labs and interventional cardiologists may face a much different approach to measuring quality and performance. We believe there are some critical elements that cath labs can implement to safeguard and promote quality; and yet, we are concerned that many of the existing approaches to measuring quality and appropriateness (such as those that rely solely on administrative data) not only fall far short of the mark, but may also end up harming patient care and access. Specifically, there is an opportunity for interventional cardiology to drive a grassroots initiative to connect with local hospitals at the state level to ensure quality standards are being met and the best in quality improvement is implemented. State by state demonstration of leadership on the physicians’ part can only serve to extend the message of consistent quality and continued focus on the best in patient care regardless of hospital size or location. Most importantly, establishing quality improvement programs in the cath lab are critical. Other steps cath labs can take to support the quality movement include: • Following the successful model of the “cath lab conference.” In regular multi-disciplinary cath lab conferences, peers discuss significant cases in an open forum. Such exercises are an important tool to promote learning and improve quality. 10 • Reporting data to a national database. Insurance databases document how many patients had a particular diagnosis or procedure, while randomized clinical trials test therapies under tightly controlled circumstances and in narrowly defined groups of patients. The NCDR, for example, uses direct clinical data from doctors and hospitals to document the cardiovascular treatments average patients receive every day, and how those treatments affect their health, helping doctors give better cardiovascular care in daily practice. By allowing hospitals and cardiologists to compare their treatments and clinical outcomes against those of similar volume and size across the nation, the NCDR also helps them to achieve the highest quality of care. • Seeking accreditation. Cath labs will benefit not just from the process of achieving accreditation, but from the continuing process of re-verification that will further prompt cath labs to constantly review their performances. Peer-reviewed studies have shown accreditation improves patient outcomes and enhances patient safety.[i] ACE, which requires CQI, provides guidance and tools to help physicians and hospitals improve their processes and outcomes, select patients according to established appropriateness criteria, and report data, assure quality and peer review. Note that accreditation for carotid stenting is now required for all facilities performing these procedures by CMS – another indication that the federal government is focusing on quality and quality improvement. While the first ACE project focuses on carotid stenting, projects for cardiac catheterization, angiography and PCI are expected to be operational by late 2010 or early 2011.[ii] There is increasing focus on cath lab quality from hospital administrators, insurers and other payers, and regulators. So far, at least, the quality improvement process for cath labs – including the role that peer review plays in that process – has been driven by interventional cardiologists and other clinicians engaged with the patients, the procedure, the science and the workings of the lab. But with the growing focus on quality and P4P efforts from payers to tie payments to quality outcomes, others less familiar with cath labs are intensifying their interest in cath lab quality. As leaders in innovation and quality improvement, interventional cardiologists believe it is the very act of working with the patient, performing the procedures, and conducting the follow up that helps us deliver the best care for our patients. Not only do we see first hand what works – we also see what needs to be done better. We have the tools and programs to improve quality, reduce variability, identify and remediate performers who are less than optimal. We owe it to our patients and to ourselves to meet and build on our professional commitment to providing the best possible care. 11 (Endnotes) 1 Kaiser Family Foundation, Summary of New Health Reform Law (Last Modified: March 26, 2010) http://www.kff.org/healthreform/upload/8061.pdf 2 Kaiser Family Foundation, Health Reform Implementation Timeline, http://www.kff.org/healthreform/8060.cfm 3 Dehmer GJ. Pay for Quality – What Every Interventional Cardiologist Needs to Know. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 68:169-172 (2006). 4 Osborne NH, et al. Do Popular Media and Internet-Based Hospital Quality Ratings Identify Hospitals with Better Cardiovascular Surgery Outcomes? JACS Jan. 2010. 210; 1: 87-92. 5 Mulvey GK, et al. Mortality and Readmission for Patients With Heart Failure Among U.S. News & World Report’s Top Heart Hospitals. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes 2009;2:558-565. 6 Rothberg MB, et al. Choosing the Best Hospital: The Limitations Of Public Quality Reporting. Health Affairs 2008 27;6:1680-1687. 7 Heupler FA Jr, Chambers CE, Dear WA, Angello DE, Helaler M and members of the Laboratory Performance Standards Committee of the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. Guidelines for internal peer review in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Cathet Cardiovasc Diag 1997; 40:21-32. 8 Burack JH, et al. Public reporting of surgical mortality: a survey of New York State cardiothoracic surgeons. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999 Oct;68(4):1195-200. 9 Omoigui NA, et al., “Outmigration for Coronary Bypass Surgery in an Era of Public Dissemination of Clinical Outcomes,” Circulation 93, no. 1 (1996): 27–33 10 Dranove D, et al. Is More Information Better? The Effects Of “Report Cards” On Health Care Providers. The Journal of Political Economy (June 2003) 111;3: 555-588. 11 Ibid. 12 Ibid. 13 TH Lee, et al. A middle ground on public accountability. N Engl J Med. (June 3, 2004) 350;23:2409-12. 14 Sternberg S. Premier hospital, high angioplasty death rate. USA Today Feb. 10, 2009. 15 Stulberg JJ, et al. Adherence to Surgical Care Improvement Project Measures and the Association With Postoperative Infections. JAMA (June 23/30, 2010) 303;24:2479-2485. 16 Werner RM, et al. Relationship Between Medicare’s Hospital Compare Performance Measures and Mortality Rates. JAMA (Dec. 13, 2006) 296; 22: 2694-2702. 17 Ibid. 18 Moscucci M, et al. Association of a continuous quality improvement initiative with practice and outcomes variations of contemporary percutaneous coronary interventions. Circulation 2006;113:814-822. 19 Smith SC, Jr, Feldman TE, Hirshfeld JW, Jr, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 Guideline Update for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention—summary article: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention). Circulation. 2006;113(1):156-175. 20 Smith SC Jr, et al. ACC/AHA/SCAI 2005 guideline update for percutaneous intervention: A report of the American College of Cardiology Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/SCAI Writing Committee to Update the 2001 Guidelines for Percutaneous Coronary intervention). J Am Coll Cardiol. Available at: http://www.acc.org/ clinical/guidelines/percutaneous/update/index.pdf 21 ACC’s NCDR Analysis Reveals Positive Trends in Heart Attack Care, July 12, 2010. http://www.cardiosource. org/News-Media/Media-Center/JACC-Releases/2010/07/NCDR-positive-trends-in-heart-attack-care.aspx 12 22 Brindis RG, Dehmer GJ. Continuous quality improvement in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Are the benefits worth the effort? Circulation 2006; 113: 767 – 770. 23 Anderson HV, Shaw RE, Brindis RG, et al. Relationship between procedure indications and outcomes of percutaneous coronary interventions by American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association task force guidelines. Circulation 2005; 112: 2786 – 2791. 24 Patel MR, et al. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC 2009 Appropriateness Criteria for Coronary Revascularization. Catheterization and Cardiovascular Interventions 73:E1–E24 (2009). 25 Ibid. 26 Parmley WW. Clinical peer review or competitive hatchet job? J Am Coll Cardiol 2000; 36: 2347. 27 Heupler FA Jr, Chambers CE, Dear WA, Angello DE, Helaler M and members of the Laboratory Performance Standards Committee of the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. Guidelines for internal peer review in the cardiac catheterization laboratory. Cathet Cardiovasc Diag 1997; 40:21-32. 28 Landro L. A Cure for Troubled Doctors: A University of California program combines data and gut instincts to determine if – and when – physicians who have been disciplined can start practicing again. The Wall Street Journal, April 13, 2010. 29 Longo DR, et al. Hospital Patient Safety: Characteristics of Best-Performing Hospitals. Journal of Healthcare Management, May 1, 2007. 30 Accreditation for Cardiovascular Excellence, Accreditation and Ongoing QA of Cardiac Catheterization and Percutaneous Coronary Intervention Programs. 13