* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Smith, Paula

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

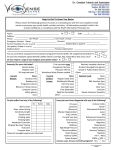

Management of Pediatric Aphakia Secondary to Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome Paula Smith, OD MCO Pediatric and Binocular Vision Resident Abstract A twelve month old presents with ocular complications associated with Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Management of aphakia and microphthalmia with contact lens and strategies optimizing visual development are described. Discussion includes differential diagnoses, associated conditions and treatments. I. Case History A 12 month old Caucasian male presented to our clinic in May 2009 as a referral for a contact lens fitting. The patient was born with Hallerman-Streif Syndrome, and as a result had visual complications of cataracts and microphthalmia, in addition to systemic gastrointestinal and skeletal issues. At two months old, the patient had both cataracts removed, leaving him aphakic. Other surgeries included tracheotomy placement at one month old, and a stomach surgery to prevent gastroesophageal reflux disease at two months and four months old. Current medications included a multi-vitamin and a fluoride supplement, with no known allergies to medications. Family ocular and medical history was unremarkable. Previous vision care included diagnoses of aphakia, sensory nystagmus, variable muscle alignment, and glaucoma suspect. Previous best achievable visual acuities were light perception in each eye. Glasses were poorly tolerated and rigid gas permeable lenses were previously unsuccessful due to an inability to maintain lens centration. Our patient was undergoing vision therapy through a state developmental program, and was using a “little room” at home to help develop spatial perception. II. Pertinent Findings Based on information obtained from the referring surgeon, trial soft contact lenses were ordered empirically to be used during the fitting. Upon first presentation to our clinic, the patient demonstrated significant physical and developmental delays. He was pleasant and compliant but unable to sit without assistance, talk, or follow directions. The first lenses we tried were custom trial lenses in hioxifilcon A standard soft material. The parameters were as follows: 1 OD: Base Curve 6.0, diameter 11.0 mm, power +45.00 D OS: Base Curve 5.50, diameter 11.0 mm, power +45.00 D The lenses maintained centration, but a small bubble was observed under the left lens. Switching lenses between the eyes revealed improved fit OS and worse fit OD. A soft lens with a 6.50 base curve was attempted, but failed to remain centered eye. The original fit was dispensed as trials. The mother was educated on disinfectant use and wear schedule and to continue with the State vision development program. She was also instructed to use auditory and tactile feedback along with bold, high contrast visual targets, but to occasionally use visual only targets to determine if visual stimuli was noticed on its own. Because of long travel, the mother was contacted four days later via telephone to determine fit consistency. The mother reported that the 5.50 base curve lens was causing irritation, and was discontinued. In an effort to minimize visual depravation to either eye, the 6.00 base curve lens was alternated between eyes halfway through each day. At the one week phone consultation, she reported the 6.0 base curve lens had fallen out of the patient’s left eye and was now lost. A second set of trials was ordered and sent to the patient with new parameters: OD: BC 6.0, diameter 11.0 mm, power +40.00 D OS: BC 5.75, diameter 11.0 mm, power +40.00 D The first in-office follow-up, 3 weeks later, revealed more information. The mother had gone back to switching the lenses between the right and left eye, due to the 6.0 base curve lens still falling out. The patient would nap in the lenses, but not sleep in them overnight. There were no problems with insertion and removal of the lenses, and no noted redness, discharge, or excessive watering. There were also no noted changes in fixation, or a difference in vision with the lenses in or out per the mother. She had been switching between hydrogen peroxide and Optifree solutions every other night. Exam findings revealed that the 6.0 base curve lens on the right eye had a superior-temporal placement, and the 5.75 base curve lens centered with no bubble on the left eye. The patient had no voluntary fixation, but did avoid bright lights and appeared to have a positive OKN drum response. Removal of the lenses and exam under a slit lamp showed 1+ protein deposits OU, with no tears, and a fluorescein evaluation of the patient’s cornea with a UV lamp revealed an intact corneal epithelium OU. Paramyd was administered OU to open the pupils to obtain an over-refraction. The contacts were re-inserted, and retinoscopy revealed a +2.00 D spherical equivalent over the right eye, and a -1.00 spherical equivalent over the left eye. 2 Silicone Hydrogel lenses were ordered with new parameters. A 3.00 diopter increase in power was added to the lenses to account for the patient’s aphakia and close working distance: OD: 5.75/11.0/+45.00 OS: 5.75/11.0/+42.00 The mother was instructed to use Hydrogen peroxide solution for overnight use, and Optifree solution for short rinses or soaks, and to return in a month for a follow-up. We instructed her to continue with visual rehabilitation activities as she had been. A second follow-up a month later showed improved results. The patient had been wearing the lenses as directed, still only napping in the lenses with the mother removing them every night. The mother had started to notice increased visual attention to lighted toys and to movies. With the new material she noted slightly more resistance of the lenses with insertion and removal, but not to a point where it was problematic. She had been successfully using the hydrogen peroxide regimen nightly, and still noted no discharge, redness, watering, or irritation. Our exam found the lenses centered with no bubbles, and no excessive movement with blinking or eye movements. The patient was now able to fixate on lights, and the nystagmus seemed to decrease slightly with the lenses on compared to with the lenses off. Lens evaluation off the eyes revealed trace protein deposits, and the epithelium was again intact OU with a fluorescein evaluation. We determined it a successful fit, and instructed the mother that with continued care of the lenses, a three month replacement schedule would be adequate. We instructed her to continue the hydrogen peroxide regimen, the use of the little room, and gave her information about sun protection for infants. We also instructed her to continue seeing the pediatric ophthalmologist as scheduled, and to let us know if she had any other questions or problems with the lenses. III. Differential Diagnosis There are no significant differential diagnoses for Hallermann-Streiff syndrome. Differential diagnoses for congenital cataracts, and the resulting leukocoria, include Retinoblastoma, Toxocariasis, Coat’s Disease, Persistent Hyperplastic Primary Vitreous (PHPV), Retinal Astorcytoma, and Retinopathy of Prematurity1. IV. Diagnosis and Discussion 3 Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome, also known as Francois Syndrome and oculomandibulodycephaly2, is a rare disease with a reported 150 cases in 19913. The syndrome was described by Hallermann in 1948, Streiff in 1950, and Francois in 19583, with seven main features: birdlike facial features with hypoplasia of the lower jaw, proportioned dwarfism, dental anomalies, hypotrichosis, cutaneous (skin) atrophy, bilateral microphthalmia, and congenital cataracts2. It is thought to be a sporadic mutation, with no genetic or sex link, and often with normal chromosome studies3. Birth weight is often normal, with about a third of cases having low birth weight or prematurity, and growth is generally diminished3. Dental anomalies may include missing teeth, malformed teeth, or an open bite, among others, and several secondary anomalies occur from the malformed facial structure, including a narrow upper airway and sleep apnea3. Other possible abnormalities in these patients may include mental deficiency, skeletal defects, genital anomalies, cardiac defects, and ear anomalies3. Of particular note are the several reported ocular anomalies, in addition to the microphthalmia and congenital cataracts. Nystagmus and strabismus are most frequently reported, followed closely by sparse eyelashes and eyebrows, blue sclera, and fundus anomalies3. A study of 6 patients with the syndrome found 5 patients to have corneal stromal opacities, believed to be non-progressive2. Other ocular anomalies, although less common, include ocular hypertension, slanting of the palpebral fissures, persistent pupillary membrane, disc or iris coloboma, vitreous degeneration, and conjunctival defects2,3. Although the literature reports occasional spontaneous reabsorbtion of bilateral cataracts in Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome, removal of the lenses decreases the risk of depravation amblyopia. For congenital cataracts, studies have shown that earlier surgery is correlated to a better final visual outcome, and recommendations for removal are after one month of age, but before three months4. Final outcome is variable, however, depending on laterality, type of cataract, and presence of coexisting ocular pathologies4. Nystagmus and strabismus lead to lower visual outcomes, as do unilateral cataracts and polar cataracts4. Intraocular lenses (IOLs) are an option to treat for aphakia, but are often not implanted in children under two years of age to avoid such risks as inflammation, subluxation, change in axial length and therefore change in needed lens power, and need for repeat surgeries5. Epikeratophakia, a once common procedure of corneal replacement, is now rarely used due to the high associated risks5. For patients without IOLs, the most common complication is development of openangle aphakic glaucoma6. Once the lens is removed, the clinical challenge is how to best treat for infantile aphakia. 4 V. Treatment, Management Although glasses are a treatment option, complications such as peripheral distortion, weight of lenses, and maintaining the optical center and vertex distance make prescribing difficult and often impractical 5. Contact lenses, although having their own complications, eliminate many of the issues that arise with spectacles. Some benefits to contacts include ease of prescription change with patient growth, minimal lens induced magnification, no prismatic effect, and constancy of prescription at all times7, 8, 9. Disadvantages include loss of lenses and associated amblyopia if unnoticed, reduced oxygen to the cornea secondary to increased center thickness, difficulty of empirically determining fitting parameters, and other risks associated with any contact lens wear: infection, neovascularization, dry eye, etc7, 8, 9. Soft lenses are generally a better option than rigid lenses, owing to wear time, oxygen permeability, and relative ease of fit. Lenses are generally fit with a larger diameter rather than small to allow lid stabilization, and avoid the lenses being blinked out by the patient. Daily wear and extended wear lenses are viable options for wear schedule, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Extended wear lenses allow the best correction at all times, and new silicone hydrogel materials with higher Dk values have made this option much safer. However, risk of infection is higher, and the lenses are less likely to be noticed by the parents if missing or blinked out. Daily wear lenses, although not optically correcting the patient at all times, force the parents to look closer at the patients’ eyes with daily insertion and removal, and a lost lens will be noticed within 12 hours7. Several studies have shown that with proper hygiene and follow-up care with either type of wear schedule, final acuities can be improved. One study shows an average of 46% of cases to achieve a final acuity of 20/40 or better (lower for unilateral cataracts, higher for bilateral)7. Unfortunately, it is difficult to determine a success rate or lowest achievable acuity because studies vary on final visual outcome due to the range of coexisting conditions, types of cataracts, and type of treatment. We expect that this patient will have a difficult time developing normal vision, given his large scope of ocular anomalies. His early depravation from cataracts, difficulty and time in obtaining a stable optical correction, and coexisting conditions of nystagmus and possible strabismus leave him at a high risk for deprivation amblyopia. Having such an extremedegree of hyperopia and no accommodative system, the patient has no chance of emmetropization. He is currently undergoing vision therapy, where motility and fixation activities are stressed. He is also using a “little room.” The little room was developed by Lilli Nielsen after a study she did on cortically blind infants from 1984-1987. It was developed to help visually impaired infants develop a better awareness of their surroundings. The room is actually a small box that sits around the infant, with auditory, tactile, and visual stimulatory objects 5 hanging within reach of the child. Through interactions and responses to the objects, the child begins to learn about spatial relations. Even with aggressive refractive and vision therapy treatment, it is probable that future treatment of this patient will require low vision aids, if not blind vision rehab such as learning to use a cane, leader dog, or Braille. However, the current combination of visual and spatial activities along with a good optical correction are the best possible treatments for this patient at this point in his life. VI. Conclusion There were many difficulties encountered with this case, which certainly made for a good learning experience. One of the biggest barriers to patient care was distance- the patient lived about an hour drive away, making good communication essential, especially when much of it took place over the phone. Another distance issue was with the contact lens company. Again, communication was important, especially finding out specific parameters for each set of lenses, and having a good idea of what the treatment and fitting plan would be before ordering the lenses. Despite the fact that we were only caring for this patient for the contact lens fit, his quantity and severity of ocular and developmental issues still made the case challenging. We picked up many clinical pearls, the first being that although rare, Hallermann-Streiff patients usually have a wide range of ocular problems, including cataracts, corneal opacities, nystagmus, and strabismus, and should be closely monitored by an eye care professional. The second pearl is that soft contact lenses are a great option for pediatric aphakes, and can be used intead of gas permeable lenses or glasses, as long as proper care and insertion and removal techniques are demonstrated by the parents or caregivers. Finally, and most important, early diagnosis and correction of congenital cataracts is essential to prevent visual deprivation, regardless of coexisting ocular or systemic conditions. As with most patients, the first step is optimizing the visual system and then optimizing the visual environment and interaction. With our patient, this meant use of the “little room” and vision therapy, and later in life may mean low vision aids, or even physical and occupational therapy. Even though this means a lot of work for the parents now, one must keep in mind the incredible flexibility of ocular and neurological systems of children; the earlier the treatment, the better and easier to adapt to for the patient, and the better the likelihood of functional improvement. Realize that relatively insignificant improvements by “normal” standards may have dramatic functional benefits later in life to a visually impaired patient. As optometrists, we have the capability of changing a life. 6 References 1. Kunimoto DY, Kanitkar KD, Makar MS. The Wills Eye Manual- Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease Fourth Edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2004. 2. Roulez FM, Schuil J, Meire FM. Corneal Opacities in Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome. Ophthalmic Genetics. 29:61-66, 2008. 3. Cohen MM Jr. Hallermann-Streiff Syndrome: A Review. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 41:488499, 1991. 4. Kim KH M.D., Ahn K M.D., Chung ES M.D., Chung TY M.D. Clinical Outcomes of Surgical Techniques in Congenital Cataracts. Korean Journal of Ophthalmology. 22(2):87-91, 2008. 5. Duckman, Robert H. Visual Development, Diagnosis, and the Treatment of the Pediatric Patient. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2006. 6. Kuhli-Hattenbach C, Luchtenberg M, Kohnen T, Hettenbach LO. Risk Factors for Complications After Congenital Cataract Surgery Without Intraocular Lens Implantation in the First 18 Months of Life. American Journal of Ophthalmology. 146(1):1-7. 2008. 7. Neumann D M.D., Weissman BA O.D. PhD, Isenberg SJ M.D., Rosenbaum AL M.D., Bateman JB M.D. The Effectiveness of Daily Wear Contact Lenses for the Correction of Infantile Aphakia. Arch Ophtalmol. 111:927-30. 1993. 8. Brabender J, Kok JHC M.D. PhD, Nuijts RMMA M.D. PhD, Wenniger-Prick LJJM M.D. PhD. A Practical Approach to and Long-Term Results of Fitting Silicone Contact Lenses in Aphakic Children After Congenital Cataract. The CLAO Journal. 28(1):31-35. 2002. 9. Ozbek Z M.D., Durak I M.D., Berk TA M.D. Contact Lenses in the Correction of Childhood Aphakia. The CLAO Journal. 28(1):28-30. 2002. 7