* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download What is Economics? 1 Chapter 11 perfect competition 1 What is

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

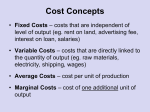

C h a p t e r 11 PERFECT COMPETITION Chapter Key Ideas Say Cheese! A. There are thousands of dairy farms in the U.S. and many of these firms are finding the milk industry a very competitive market. As a result, many are leaving the milk industry and using their resources to enter into the competitive cheese market. B. The consumer electronics markets are also highly competitive. In the past few years consumers have seen significant declines in the price of personal computers, palm-held digital assistant devices, and DVD player/recorders. C. We can explain these observed changes in market price and firm output as firms operating within a market exhibiting perfect competition respond to shifting consumer demand and technological change. Outline I. What Is Perfect Competition? A. Perfect competition describes an industry in which: 1. Many firms sell identical products to many buyers. 2. There are no restrictions to entry into the industry. 3. Established firms have no advantages over new ones. 4. Sellers and buyers are well informed about prices. B. Perfect competition arises when: 1. Perfect competition occurs when the firms’ minimum efficient scale are small relative to demand for the good or service, and 2. when each firm is perceived to produce a good or service that has no unique characteristics, so consumers don’t care from which firm they buy. C. In perfect competition, each firm is a price taker. 1. A price taker is a firm that cannot influence the market price and sets its own price at the market price. 2. Each firm produces a tiny proportion of the entire market and consumers are well informed about the prices charged by other firms. 252 CHAPTER 11 3. Each firm’s output is a perfect substitute for the output of the other firms, so the demand for each firm’s output is perfectly elastic. D. Economic Profit and Revenue The goal of each firm is to maximize economic profit, which equals total revenue minus total cost. 1. A firm’s total cost is the opportunity cost of production, which includes a normal profit—the return that the entrepreneur can expect to receive on the average in an alternative business. 2. A firm’s total revenue equals price, P, multiplied by quantity sold, Q, or P Q. 3. A firm’s marginal revenue is the change in total revenue that results from a one-unit increase in the quantity sold. In perfect competition the price remains the same as the quantity sold changes, which means that marginal revenue equals the market price. 4. Figure 11.1 illustrates a firm’s revenue concepts. a) Figure 11.1a shows how the market demand and supply determine the equilibrium market price that the firm must take. b) Figure 11.1b shows the demand curve for the firm’s product, which is also its marginal revenue curve. The firm’s demand curve is perfectly elastic. c) Figure 11.1c shows the firm’s total revenue curve, with total revenue increasing as a constant rate. II. The Firm’s Decisions in Perfect Competition A. A perfectly competitive firm faces two types of constraints: PERFECT COMPETITION 253 1. A market constraint is summarized by the market price and the firm’s revenue curves. 2. A technology constraint is summarized by firm’s product curves and cost curves (from Chapter 10). B. The perfectly competitive firm must make two sequential decisions in the short run and two sequential decisions in the long run: 1. In the short run, each firm has a given plant size and the number of firms in the industry is fixed. a) A firm must decide in the short-run whether to produce positive quantity of output or to shut down completely. b) If the firm’s decision is to produce a positive quantity of output, then the firm must choose what quantity to produce. 2. In the long run, firms can enter or exit the industry and change their plant size. a) A firm must decide in the long-run whether to stay in or exit from the industry. b) If the firm’s decision is to stay in the industry, then the firm must choose whether to change its plant size. 254 CHAPTER 11 C. A perfectly competitive firm chooses the output that maximizes its economic profit. 1. One way to find the profit maximizing output is to use the total revenue and total cost curves. a) Figure 11.2 shows the total revenue and total cost curves, as well as the profit for each level of output for the sweater making firm. b) At relatively low and relatively high levels of outputs, the firm incurs an economic loss where total cost exceeds total revenue. 2. At two separate levels of output, total revenue exactly equals total cost. Such an output is called a break-even point. At these levels of output the entrepreneur earns normal profit. 3. The output at which total revenues exceed total cost by the largest amount is the profitmaximizing level of output. D. Marginal Analysis 1. The firm can use marginal analysis to determine the profit-maximizing level of output to produce. 2. Profit is maximized by producing the level of output at which marginal revenue, MR, equals marginal cost, MC. That is: MR = MC. PERFECT COMPETITION 3. 255 Figure 11.3 shows the level of output where MR = MC for the sweater making firm. These two curves intersect because MR is constant as output increases and MC rises as output increases. a) If MR > MC, economic profit increases if the firm increases output. b) If MR < MC, economic profit decreases if the firm increases output. c) If MR = MC, economic profit decreases regardless if the firm increases or decreases output, so economic profit is maximized at this specific level of output. E. Profits and Losses in the Short Run 1. The maximum profit for the firm is not always a positive amount. We compare the firm’s average total cost, ATC, at the profit maximizing output to the market price, P, to determine whether a firm is earning an economic profit, earning a normal profit, or incurring an economic loss. 2. Figure 11.4 shows the three possible profit outcomes at the profit maximizing level of output. a) As in Figure 11.4a, if the market price equals the firm’s ATC, the firm earns zero economic profit (a normal profit). 256 CHAPTER 11 b) As in Figure 11.4b, if the market price is greater than the firm’s ATC, the firm earns a positive economic profit. c) F. As in Figure 11.4c, if the market price is less than the firm’s ATC, the firm incurs an economic loss, which means economic profit is negative. A perfectly competitive firm’s short run supply curve shows how the firm’s profitmaximizing output changes as the market price varies, other things remaining the same. 1. Figure 11.5 shows how to derive a firm’s short-run supply curve. 2. Because the firm produces the output at which marginal cost equals marginal revenue, and because marginal revenue equals price, the firm’s supply curve is its marginal cost curve (above the shutdown point). G. A firm may temporarily shut down it plant. 1. If the market price is less than the firm’s minimum AVC, the firm will shut down temporarily and incur a loss equal to total fixed cost. a) The total fixed cost is the largest loss that the firm must bear. b) If the firm were to produce a unit of output at price below average variable cost, it would incur an additional (and avoidable) loss, so at any price less than the firm’s average variable cost it shuts down. 2. The shutdown point is the level of output and price at which the firm’s total revenues just cover its total variable cost. a) The shutdown point is the level of output at which AVC is minimized. b) The shutdown point is also the point at which the MC curve crosses the AVC curve. c) 3. At the shutdown point, the firm is indifferent between producing and shutting down temporarily. If the market price exceeds the minimum AVC, the firm remains open and produces the quantity at which MC equals the market price. a) In this case, the firm’s total revenues are greater than its total variable cost. b) Because the firm’s total revenue exceeds its total variable cost, the firm can use the difference to pay at least part of its total fixed cost. PERFECT COMPETITION 4. 257 The firm’s short-run supply curve is its MC curve at prices that are equal to or greater than its minimum AVC. a) The firm’s quantity supplied is zero at prices below the minimum AVC. b) The firm’s supply curve has a break at point where the market price is equal to its minimum AVC. c) The firm will not produce quantities between zero and the shutdown quantity (determined by its minimum AVC). H. The short-run industry supply curve shows how the quantity supplied by the industry at each price when the plant size of each firm and the number of firms remain constant. 1. Figure 11.6 shows an industry supply curve. a) The quantity supplied by the industry at any given market price is the sum of the quantities supplied by all the firms in the industry at that price. b) The industry supply curve is perfectly elastic at a price equal to the firms’ minimum AVC (the shutdown price) because some firms will produce their shutdown quantity and other firms will produce zero units of output. 258 CHAPTER 11 III. Output, Price, and Profit in Perfect Competition A. Short-run industry supply and industry demand determine the market price and output in a perfectly competitive market. B. Figure 11.7 shows the short-run equilibrium at the intersection of the demand and supply curves and how changes in market demand can change the short-run equilibrium price and quantity in the market. 1. If the market demand increases, the demand curve shifts rightward and the equilibrium market price rises. As a result, firms increase their production along their respective supply curves. 2. If market demand decreases, the demand curve shifts leftward and the equilibrium market price falls. As a result, firms decrease their production along their respective supply curves. C. A Change in Demand 1. A firm may earn an economic profit, earn a normal profit, or incur an economic loss during short-run market equilibrium. 2. Whichever of these states exists will determine the two sequential decisions that the firm must make in the long run. a) The firm must decide whether to enter or exit the industry. b) If the firm decides to enter into or stay in the industry, it must decide whether to change its plant size. D. The competitive market exhibits adjustments to changes in the long run market equilibrium price and quantity. 1. New firms are motivated to enter an industry in which the existing firms are earning an economic profit. 2. Existing firms are motivated to exit an industry in which they incur an economic loss. PERFECT COMPETITION 3. 259 Figure 11.8 shows the effects on market equilibrium price and quantity of firm entry into and exit from the industry in the long run. a) As new firms enter a market, the industry supply increases and the supply curve shifts rightward. The market price falls and the economic profit of each firm decreases. b) As firms exit a market, the industry supply decreases and the supply curve shifts leftward. The market price rises and the economic loss of the surviving firms decreases. 4. Firms are no longer motivated to enter or exit the industry when economic profits or economic losses have been eliminated and the firms within the industry return to earning normal profits. E. Changes in Plant Size Figure 11.9 shows the effects of changes in plant size. F. 1. Firms change their plant size whenever it is profitable to do so. 2. If ATC exceeds the minimum longrun average cost, the firms will change their plant size to lower production costs and increase profits. Long-run equilibrium occurs in a competitive industry when: 1. Economic profit for firms remaining in the industry is zero, so firms are no longer motivated to either enter or exit the industry. 2. Long-run average cost for each firm in the industry is at its minimum, so firms are not motivated to change their existing plant size. 260 CHAPTER 11 III. Changing Tastes and Advancing Technology A. Figure 11.10 shows the effects of a permanent decrease in demand on an industry and on a firm within the industry. 1. A decrease in market demand shifts the demand curve leftward. The market price decreases and the market quantity supplied in the market by all firms decreases. (There is a movement down the market supply curve.) 2. The lower market price is less than each firm’s minimum ATC and each firm incurs an economic loss. 3. Economic losses motivate firms to exit the industry, decreasing short-run supply and shifting the industry supply curve leftward. 4. As industry supply decreases, the market price rises (there is a movement up the demand curve) while the market quantity continues to decrease (because firms are exiting the industry). 5. As the market price is rising, each firm that remains in the industry increases its production in a movement along its own respective short-run supply curve. 6. A new long-run equilibrium price and quantity occurs when the market price has risen to again equal the minimum ATC for each firm still in the industry. These firms no longer incur economic losses and are no longer motivated to leave the industry. 7. The main difference between the old equilibrium and the new equilibrium is that the number of firms in the industry has declined. B. There are similar but opposite effects from a permanent increase in demand on a firm within the industry. 1. An increase in market demand shifts the demand curve rightward. The market price increases and the market quantity supplied in the market by all firms increases (There is a movement up the market supply curve). 2. The higher market price exceeds each firm’s minimum ATC and firms enjoy an economic profit. PERFECT COMPETITION 261 3. Economic profits motivate firms outside the industry to enter the industry, increasing short-run supply and shifting the industry supply curve rightward. 4. As industry supply increases, the market price falls (there is a movement down the demand curve) while the market quantity continues to increase (because firms are entering the industry). 5. As the market price falls, each firm in the industry decreases its production in a movement along its own respective short-run supply curve. 6. A new long-run equilibrium price and quantity occurs when the market price has fallen to equal the minimum ATC for each firm in the industry. These firms no longer enjoy economic profits and firms outside the industry are no longer motivated to enter the industry. 7. The main difference between the old equilibrium and the new equilibrium is that the number of firms in the industry has increased. C. The change in the long-run equilibrium price following a permanent change in demand depends on external economies and external diseconomies. 1. External economies are factors beyond the control of an individual firm that lower the firm’s costs as the industry output increases. 2. External diseconomies are factors beyond the control of a firm that raise the firm’s costs as industry output increases. D. In the absence of external economies or external diseconomies, a firm’s production costs remain constant as industry output changes. 1. Figure 11.11 illustrates the three possible cases and shows the long-run industry supply curve, which shows how the quantity supplied by an industry varies as the market price varies after all the possible adjustments have been made, including any changes in plant size and the number of firms in the industry. 2. Figure 11.11a shows that in the absence of external economies or external diseconomies, the equilibrium price remains constant when market demand increases. 3. Figure 11.11b shows that when external diseconomies are present, the equilibrium price rises when demand increases. 4. Figure 11.11c shows that when external economies are present, the equilibrium price falls when demand increases. 262 CHAPTER 11 C. New technologies are constantly being discovered. Such technology changes lower production costs. 1. A new technology enables firms to produce at a lower long run average cost. This lowers the firm’s marginal cost, shifting the firms’ cost curves downward. 2. Those firms that adopt the new technology earn an economic profit. 3. New-technology firms enter the industry and old-technology firms either exit or adopt the new technology. 4. Industry supply increases and the industry supply curve shifts rightward. The equilibrium price falls and quantity increases. 5. Eventually, a new long-run equilibrium price and quantity emerges in the industry in which all the firms use the new technology. The price falls to the minimum ATC and each firm earns normal profit. 6. The adjustment process as old-technology firms exit or adopt the new technology and new-technology firms enter can create great changes in the prosperity of the local community. The dynamics of a competitive market imply that some regions experience economic decline while others experience economic growth. V. Competition and Efficiency A. Efficient Use of Resources The competitive market can achieve the efficient use of resources 1. Resources are used efficiently when no one can be made better off without making someone else worse off. 2. Resource use is efficient when marginal benefit equals marginal cost. B. We can describe an efficient use of resources in terms of the choices made by consumers and firms whose decisions are coordinated through market equilibrium. 1. Analyzing consumer and producer choices: a) We derive a consumer’s demand curve by finding how the best (most valued by the consumer) budget allocation changes as the price of a good changes. Consumers get the most value out of their resources by consuming at any point along their demand curves, which are also their marginal benefit curves. b) Competitive firms produce the quantity that maximizes profits. The supply curves are derived from the profit maximizing quantities firms are willing to supply at each market price. Firms get the most value out of their resources at any point along their supply curves, which are also their marginal cost curves. 3. Understanding the implications of market equilibrium: a) In a competitive market equilibrium the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied, which implies that marginal benefit equals marginal cost. b) All gains from trade in this market have been realized. Gains from trade are the sum of consumer surplus (the area under the demand curve but above the price) plus producer surplus (the area under price but above the supply curve). PERFECT COMPETITION 4. 263 Figure 11.12 shows an efficient outcome in a perfectly competitive industry. a) The competitive equilibrium is efficient if there are no external benefits or costs. b) External benefits are benefits that accrue to people other than the buyer of a good or service. c) External costs are costs that are borne by someone other than the producer of the good or service. Reading Between the Lines A news article about dairy firms exiting the highly competitive milk industry and entering into various competitive cheese markets such as Buffalo mozzarella. The analysis shows the effects on the market price and quantity and the dynamics of the competitive market. New in the Seventh Edition The Reading Between the Lines looks at the dairy industry rather than Connecticut’s maple syrup industry to illustrate the dynamics of a very competitive market. Te a c h i n g S u g g e s t i o n s Challenges and primary goals Students find the topic of competitive market dynamics challenging. Part of their problem is that understanding the dynamics requires a strong understanding of the cost curves of the previous chapter, yet many of them still have only a shaky grasp of that important material. So emphasize the cumulative nature of economics and remind the students of the huge payoff from mastering material a bite at a time (see the firm owner’s quick decision example in the point of interest example toward the end of the lecture outline constructed for this chapter). You can help your students by emphasizing the two primary goals of this chapter: (1) To derive the market supply curve in a competitive industry and (2) to deepen your students’ understanding 264 CHAPTER 11 of how competition among self-interested consumers and producers will move society’s resources from less valued uses to more highly valued uses, achieving an efficient allocation in the eyes of society. Explain that although Chapter 3 (Demand and Supply) and Chapter 5 (Efficiency and Equity) covered these same topics, they did so at a level that is one step removed from the decision makers who make it happen. Remind the students that they’ve seen how consumer decisions lead to the best use of a household’s income. Point out that now they are going see how producer decisions are made and how they interact with consumer decisions. 1. The range of market types. Remind the students of what they learned in Chapter 9 about the spectrum of markets that range from perfect competition to monopoly. The perfect competition model serves as a benchmark and its predictions work in a wide range of real markets. Set the scene for appreciating the power of the perfect competition model with a physical analogy. Explain that physicists often use the model of a “perfect vacuum” to understand our physical world. For example, to predict how long it will take a 50 pound steel ball to hit the ground if it is dropped from the top of the Empire State Building, you will be very close to the actual time if you assume a perfect vacuum and use the formula that applies in that case. Friction from the atmosphere is obviously not zero, but assuming it to be zero is not very misleading. In contrast, if you want to predict how long it will take a feather to make the same trip, you need a much fancier model! Economists use the model of “perfect competition” in a similar way to understand our economic world. Emphasize to students that although no real world industry meets the full definition of perfect competition, the behavior of firms in many real world industries and the resulting dynamics of their market prices and quantities can be predicted to a high degree of accuracy by using the model of perfect competition. Understanding the price taking firm. Spend a few minutes providing intuition to ensure that your students understand why firms in perfect competition are price takers. On the one hand, they could offer to sell for a lower price but they’d be giving profits away because they can sell all they want at the going market price. On the other hand, they can ask for a higher price but not even one consumer will pay because consumers know where to buy an exact substitute at a lower price. You might like to note that if the market is not in equilibrium, then the firm isn’t really a price taker. If there is a market shortage then firms can temporarily get away with charging a higher price. That’s how prices rise in the market. If there is a surplus then firms can offer a lower price to move more of their product. That’s how prices fall. In equilibrium, however, there is nothing a firm can do but take the going market price, and competitive markets arrive at equilibrium price quickly. 2. Do firms really choose the output that maximizes profit? It is useful to explain to your students that many big firms routinely make tables using spreadsheets describing total revenues, total costs, and economic profits earned for each product line and market that are similar to those in Figure 11.2. However, most firms (and certainly most small firms like Cindy’s sweater knitting firm) don’t make such careful and extensive calculations. Nonetheless, these firm owners do make their decisions at the margin. They can figure out how much it will cost to hire one more worker and how much output that worker will produce. So they can figure out their marginal cost—wage rate divided by marginal product. They can compare that number with the price. In effect, they are choosing input and output levels “at the margin.” 3. The mechanics of the shutdown analysis will be a lot easier to explain once the students have thought about these real situations with which they are familiar. Operating a business at a loss: Students often have a hard time understanding why operating at an economic loss can be the best action for a firm owner. The key is emphasizing: PERFECT COMPETITION 265 The firm owner’s short-run decisions are made after some irrevocable commitments have generated sunk costs. The firm owner considers only avoidable future costs when making decisions. Unavoidable costs should have no impact on the decision (other than to learn from them). For the firm to continue to produce output, the firm owner needs only to receive revenues that exceed any avoidable costs, not necessarily all total costs. The profit maximization goal doesn’t require the firm owner to earn a positive economic profit in the short run, just the minimum economic loss. Operating a business at zero economic profit. Students are often skeptical that a zero economic profit is an acceptable outcome for a hard working entrepreneur. The key is to reinforce the meaning of normal profit. A rational decision for a firm owner is one that is based on a weighing of the full opportunity cost of each alternative against its full benefits. For a firm owner this means weighing the total revenues received against the total opportunity cost for each alternative use of his or her time, effort and resources. 4. 5. Opportunity cost includes the benefits from forgone opportunities as well as explicit costs paid. One of these forgone opportunities is that of the entrepreneur pursuing his or her next best career opportunity. The value of this forgone opportunity is normal profit. When a firm earns zero economic profit, the entrepreneur earns a normal profit and enjoys the same benefits as those that would be available in his or her next best career opportunity. There is no incentive for the firm owner to change his or her activity. Watching the work of the invisible hand. The power of the market to make firms respond to consumers’ changing demands become visible to the student in this chapter. When you teach the dynamics of firm entry and exit do the analysis with a specific (and current or recent) example with which the students can identify. Computers, palm pilots and internet ISPs are good examples for an increase in demand. Audio cassette tapes and analogue video cameras are good examples for a decrease in demand. Pulling it all together. In this chapter you can show your students what they’ve learned and pull together the entire course to date. Begin by reiterating the two primary goals of this chapter and then note that you are now dealing with the second goal. Emphasize that the pressures of competition force self-interested firms to produce incredible long run results: Each firm produces at the lowest possible average total cost, as illustrated by: producing at the minimum point of the long run average cost curve. Each consumers pays the lowest possible price that keeps firms in business and willing to voluntarily produce the goods and services, as illustrated by: P = minimum ATC. Each firm is motivated to use the latest available, least-cost technology, as is illustrated by: firms can enjoy profits in the short run only if they can successfully charge a lower price than their competitors. Firms produce the efficient quantity price, as is illustrated by firms choosing to produce at marginal benefit equals marginal cost to maximize profits (assuming no external costs to society). The forces of market competition, which Adam Smith called an “invisible hand,” guide selfinterested firms to produce output and charge prices that maximize the value of society’s scarce resources and promote the social interest. 266 CHAPTER 11 The Big Picture Where we have been: Chapter 11 relies heavily on the productivity and cost analysis material of chapter 10, the marginal analysis and efficiency issues introduced in chapter 2 and chapter 5, and the concept of economic profit introduced in Chapter 9. Where we are going: Chapter 11 is the first of three chapters that explore the price and output decisions of firms under various market characteristics. Chapter 11 studies perfect competition, Chapter 12 monopoly, and Chapter 13 monopolistic competition and oligopoly. All three chapters use cost curves, marginal analysis, and the concept of efficiency. O ve r h e a d Tr a n s pa r e n c i e s Transparency Text figure Transparency title 66 Figure 11.2 Total Revenue, Total Cost, and Economic Profit 67 68 Figure 11.3 Figure 11.4 69 Figure 11.5 Profit-Maximizing Output Three Possible Profit Outcomes in the Short Run A Firm’s Supply Curve 70 Figure 11.7 Short-Run Equilibrium 71 Figure 11.8 Entry and Exit 72 Figure 11.12 Efficiency of Competition Electronic Supplements MyEconLab MyEconLab provides pre- and post-tests for each chapter so that students can assess their own progress. Results on these tests feed an individualized study plan that helps students focus their attention in the areas where they most need help. Instructors can create and assign tests, quizzes, or graded homework assignments that incorporate graphing questions. Questions are automatically graded and results are tracked using an online grade book. PowerPoint Lecture Notes PowerPoint Electronic Lecture Notes with speaking notes are available and offer a full summary of the chapter. PowerPoint Electronic Lecture Notes for students are available in MyEconLab. PERFECT COMPETITION 267 Instructor CD-ROM with Computerized Test Banks This CD-ROM contains Computerized Test Bank Files, Test Bank, and Instructor’s Manual files in Microsoft Word, and PowerPoint files. All test banks are available in Test Generator Software. Additional Discussion Questions 1. Examples of seemingly peculiar short run behavior by firm owners. Students should see how a clear understanding a perfectly competitive market justifies firm behavior that otherwise might appear somewhat peculiar: Late night TV is full of zany TV commercials with firm owners who claim “I must be crazy, because I’m losing money on every sale!” Why do they advertise to increase sales if they’ll cause the owner to lose even more money? At first, it appears that these owners must be lying about “losing money on every sale.” Yet their claim is potentially true, as the various firms in their industry may currently face a market price above AVC, but below ATC in the short run. In this case they would remain in business and continue advertising, despite “losing money on every sale” because they are earning revenues above their variable costs to at least help contribute toward paying their fixed cost obligations to their debtors. Why do the same farmers always complain of losing money but never seem to exit the industry? Point out that agriculture is a collection of highly competitive markets where farming operations typically have an extremely high capital-to-labor ratio. This makes the typical farm’s ratio of fixed costs to variable costs very high relative to most industries. Also, much of a farmer’s capital is in the form farmland, which is difficult to sell during falling agriculture prices, lengthening the farmer’s short run time frame. In this case, the dollar difference between market price and minimum AVC will be rather large. As long as market price exceeds AVC, the farmer will minimize losses by continuing to produce output over an extended short run time frame. 2. The dynamics of the competitive market generate socially efficient resource allocations. Emphasize that when firms go out of business and exit the industry, this brings the market closer to the efficient outcome. Ask the following questions: What is implied about efficiency if the average cost of producing a good exceeds the price people are willing to pay for it? Remind the students that a firm’s cost curves reflect the opportunity cost to society of the firm using the resources to make the goods in its market (the resources could be making goods in some other market that could bring benefits to society). The demand curve reflects the value society places on each level of quantity of goods produced. If the price people are willing to pay is determined by the market supply and demand and going market price is less than the opportunity cost of producing the last unit of the good, using more resources to increase output creates fewer net benefits for society than could be generated if the resources were used elsewhere in other markets. What happens to the resources that were used by a firm for production when that firm exits the industry? Point out that when price falls below ATC, this generates an economic loss for the firm. This is a signal from a society of consumers to the owner of the resources that he or she will benefit from reallocating the resources to making different goods and services from the same resources that could represent greater value to society. How can an increase in net benefits to society be generated from the systematic destruction of firms leaving the market? A famous economist named Joseph Schumpeter coined the phrase “creative destruction” to describe the dynamics of a competitive market. While the productive capacity of a perfectly competitive industry facing declining consumer demand is ultimately 268 CHAPTER 11 destroyed, the resources themselves are not destroyed. They are simply released to firms in other markets to create goods and services that are relatively more valuable to society. This “destruction” of an industry creates goods of greater social value in another industry. That is Schumpeter’s “creative destruction.” 3. The “Invisible Hand” of competition. The students should develop an appreciation for the incredibly coordinated and socially beneficial activity behind the dynamics of a competitive market, despite the lack of any central coordinating body of decision makers responsible for monitoring and controlling the use of society’s resources. Ask the following questions: What makes the self-interested firms produce and sell output at the lowest possible cost per unit in the long run? The students should see that, although each firm seeks to maximize profit rather than social benefits, competition renders the firm unable to charge a price any higher than the minimal amount necessary to cover its cost of production. 4. What makes all the self-interested firms adopt the latest available technology for producing at the lowest opportunity cost possible over time? Emphasize that competitive firms cannot increase their economic profits by raising the market price, so they must search for ways to increase economic profit through falling production costs. This means that firms are constantly seeking out the latest production technologies to find a cost advantage over their competitors. If the other firms failed to adopt this low-cost production technology, they would suffer an economic loss when those that do adopt the technology lower their prices to increase market share. Firms that refuse to adopt the technology must then match a lower market price to retain their market shares, causing them to bear an economic loss and face an eventual exit from the market. Examples of external economies and diseconomies. Get the students interested in thinking about what might cause the value of long run average cost to rise or fall with output. Ask the following questions: What markets might exhibit external economies (a decrease in the cost per unit to produce a good or service)? Suggest evidence of markets with external economies by mentioning geographical areas known for their industry, like New York City’s financial districts, or Silicon Valley’s high technology industries. Sometimes close geographical proximity of mobile, abundant, and highly specialized laborers can decrease the cost of doing business for firms in that area, resulting in firms experiencing falling long run average costs over time. What markets might exhibit external diseconomies (an increase in the cost per unit to produce a good or service)? This one is a little more difficult, but perhaps the market for defense goods like nuclear submarines or stealth bombers would be an example of external diseconomies. If the government desired to contract with private firms for a significant increase in the number of these machines, many different firms might enter the market, raising the demand for scientists and engineers with rare technical skills and expertise (unique human capital). As the quantity of output increases, the demand for the labor of these highly skilled workers would increase but the supply would be relatively low. The wages commanded by these laborers would climb higher and higher, raising the resource costs for firms, increasing the long run average cost of production. PERFECT COMPETITION 269 Answ ers to the Review Quizzes Page 239 1. One firm’s output is a perfect substitute for another firm’s output. This implies that each firm cannot unilaterally influence the market price for which it can sell its good or service. It must accept, or “take” the market equilibrium price—hence the term, price taker. 2. The market demand for the goods and services in a perfectly competitive market is downward sloping. However, no single firm in this market can determine the price at which to sell its output. This means that a price taker firm must take the equilibrium market price as given, and the firm faces a perfectly elastic demand curve. 3. The perfectly competitive firm’s demand curve is a horizontal line at the market price. This means that the price it receives is the same every unit sold. The marginal revenue received by the firm is the change in total revenue from selling one more unit, which is the constant market price. This means the perfectly competitive firm’s demand curve is the same as its marginal revenue curve. 4. Total revenue equals the price of a firm’s output multiplied by the number of units of output sold, or P Q. If the firm can sell each and every unit at a constant market price, then the addition to total revenue for each unit sold will be constant. This means the slope of the total revenue curve is positive and linear. 1. A firm’s profit is maximized by producing the level of output at which marginal revenue for the last unit produced equals its marginal cost, or MR = MC. In a perfectly competitive market, MR is equal to the market price P for all levels of output. This implies that a perfectly competitive firm will always maximize profit by producing output where P = MC. 2. The lowest price a firm will produce positive output is that price which equals the firm’s minimum AVC. At this price the firm has just enough total revenue to cover its total variable costs. The firm’s loss is equal to its fixed costs. At any lower market price, the firm’s loss would be greater than its fixed costs. This implies that the firm can avoid losses that are greater than its fixed cost by shutting down its plant and stopping production. 3. The firm will produce output as long as it receives a price greater than the min AVC and it will choose the level of output where MC = P. This means the firm’s supply curve is the firm’s MC curve above min. AVC. 4. A perfectly competitive industry’s short-run supply curve equals the horizontal summation of each individual firm’s supply curve. That is, the amount supplied by the total industry equals the sum of what each firm in the industry supplies at a given price. 1. When a firm in a perfectly competitive market is producing the quantity that maximizes profit, its marginal cost is equal to the marginal revenue. Because the marginal revenue is equal to the market price, this means that the marginal cost is equal to the marginal revenue is equal to the market price. 2. When the existing firms in a perfectly competitive industry experience economic profit, firms from outside the industry enter the market, increasing market supply. The market supply curve shifts rightward, driving the equilibrium market price down and lowering the firm’s profits in the industry. In the long run, the market price falls to a level such that the firms in the market Page 245 Page 249 270 CHAPTER 11 earn only a normal profit. The equilibrium market output has increased as a result of the entry of new firms. 3. When the existing firms in a perfectly competitive industry experience economic losses, firms exit the industry, decreasing market supply. This shifts the market supply curve leftward, driving the equilibrium market price up and raising firm profits in the industry. In the long run, the market price returns to the original market equilibrium level, equilibrium market output has decreased, and economic profit for each firm remaining in the industry returns to zero. 1. A permanent decrease in demand decreases the market quantity, and the market price falls below ATC for each firm. In the short run, firms in the industry experience an economic loss, which leads to firms exiting the industry. This exit shifts the industry supply curve leftward, raising the market price as the market quantity continues to decrease. The increase in market price shrinks the economic loss for each remaining firm. Exit continues until the price again equals the minimum point on each firm’s ATC curve. At this point, firms return to zero economic profit and exit stops. In the long run, the market price returns to the original level, market output has decreased, and economic profit for each firm returns to zero. 2. A permanent increase in demand increases the market quantity, and the market price rises above ATC for each firm. In the short run, firms in the industry experience an economic profit, attracting firms from outside the industry to enter the industry. This entry shifts the industry supply curve rightward, decreasing the market price as the market quantity continues to increase. The fall in the market price shrinks the firms’ economic profit until the price again equals the minimum point on each firm’s ATC curve. At this point, firms return to zero economic profit and entry stops. In the long run, the market price returns to the original level, market output has increased, and economic profit for each firm returns to zero. 3. Technological advances result in lower cost curves for the firm that adopts them and initially these firms earn an economic profit. This causes two actions to occur in the market: i) firms from outside the industry that have adopted the new technology enter the market, ii) firms with old technology either exit the market or adopt the new technology. These two actions cause the industry supply curve to shift rightward, decreasing market price and increasing market quantity. In the long run, all firms in the industry will be new technology firms, economic profit for each firm will return to zero, market quantity will increase, and market price will fall to the new minimum ATC for each firm. Page 253 PERFECT COMPETITION 271 Answ ers to the Problems 1. a. b. c. 2. a. b. c. 3. a. Quick Copy’s profit-maximizing quantity is 80 pages an hour. Quick Copy maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In perfect competition, marginal revenue equals price, which is 10 cents a page. Marginal cost is 10 cents when Quick Copy produces 80 pages an hour. Quick Copy’s profit is $2.40 an hour. Profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals $8.00 an hour (10 cents a page multiplied by 80 pages). The average total cost of producing 80 pages is 7 cents a page, so total cost equals $5.60 an hour (7 cents multiplied by 80 pages). Profit equals $8.00 minus $5.60, which is $2.40 an hour. The price will fall in the long run to 6 cents a page. At a price of 10 cents a page, firms make economic profit. In the long run, the economic profit will encourage new firms to enter the copying industry. As they do, the price will fall and economic profit will decrease. Firms will enter until economic profit is zero, which occurs when the price is 6 cents a copy (price equals minimum average total cost). Jerry’s profit-maximizing quantity is 300 ice cream cones a day. Jerry’s maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In perfect competition, marginal revenue equals price, which is $3 a cone. Marginal cost is $3 when 300 cones a day are produced. Jerry’s profit is $150 a day. Profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals $900 a day ($3 a burger multiplied by 300 cones). The average total cost of producing 300 ice cream cones is $2.50 a cone, so total cost equals $750 a day ($2.50 multiplied by 300 cones). Profit equals $900 minus $750, which is $150 a day. In the long run, the price will fall to $2 a cone. At a price of $3 a cone, firms make economic profit. In the long run, the economic profit will encourage new firms to enter and set up an ice cream stand on the beach. As they do, the price will fall and economic profit will decrease. Firms will enter until economic profit is zero, which occurs when the price is $2 a cone (price equals minimum average total cost). (i) At $14 a pizza, Pat’s profit-maximizing output is 4 pizzas an hour and economic profit is $10 an hour. Pat’s maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In perfect competition, marginal revenue equals price, which is $14 a pizza. Marginal cost is the change in total cost when output is increased by 1 pizza an hour. The marginal cost of increasing output from 3 to 4 pizzas an hour is $13 ($54 minus $41). The marginal cost of increasing output from 4 to 5 pizzas an hour is $15 ($69 minus $54). So the marginal cost of the fourth pizza is half-way between $13 and $15, which is $14. Marginal cost equals marginal revenue when Pat produces 4 pizzas an hour.. Economic profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals $64 ( $14 multiplied by 4). Total cost is $54, so economic profit is $10. (ii) At $12 a pizza, Pat’s profit-maximizing output is 3 pizzas an hour and economic profit is $5. Pat’s maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Marginal revenue equals price, which is $12 a pizza. Marginal cost of increasing output from 2 to 3 pizzas an hour is $11 ($41 minus $30). The marginal cost of increasing output from 3 to 4 pizzas an hour is $13. So the marginal cost of the third pizza is 272 CHAPTER 11 b. c. d. 4. a. half-way between $11 and $13, which is $12. Marginal cost equals marginal revenue when Pat produces 3 pizzas an hour. Economic profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals $36 ($12 multiplied by 3). Total cost is $41, so economic profit is $5. (iii) At $10 a pizza, Pat’s profit-maximizing output is 2 pizzas an hour and economic profit is $10. Pat’s maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Marginal revenue equals price, which is $10 a pizza. Marginal cost of increasing output from 1 to 2 pizzas an hour is $9 ($30 minus $21). The marginal cost of increasing output from 2 to 3 pizzas an hour is $11. So the marginal cost of the second pizza is half-way between $9 and $11, which is $10. Marginal cost equals marginal revenue when Pat produces 2 pizzas an hour. Economic profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals $20 ($10 multiplied by 2). Total cost is $30, so economic profit is $10. Pat’s shutdown point is at a price of $10 a pizza. The shutdown point is the price that equals minimum average variable cost. To calculate total variable cost, subtract total fixed cost ($10, which is total cost at zero output) from total cost. Average variable cost equals total variable cost divided by the quantity produced. For example, the average variable cost of producing 2 pizzas is $10 a pizza. Average variable cost is a minimum when marginal cost equals average variable cost. The marginal cost of producing 2 pizzas is $10. So the shutdown point is a price of $10 a pizza. Pat’s supply curve is the same as the marginal cost curve at prices equal to or above $10 a pizza and the y-axis at prices below $10 a pizza. Pat will exit the pizza industry if in the long run the price is less than $13 a pizza. Pat’s Pizza Kitchen will leave the industry if it incurs an economic loss in the long run. To incur an economic loss, the price will have to be below minimum average total cost. Average total cost equals total cost divided by the quantity produced. For example, the average total cost of producing 2 pizzas is $15 a pizza. Average total cost is a minimum when it equals marginal cost. The average total cost of 3 pizzas is $13.67, and the average total cost of 4 pizzas is $13.50. Marginal cost when Pat’s produces 3 pizzas is $12 and marginal cost when Pat’s produces 4 pizzas is $14. At 3 pizzas, marginal cost is less than average total cost; at 4 pizzas, marginal cost exceeds average total cost. So minimum average total cost occurs between 3 and 4 pizzas—$13 at 3.5 pizzas an hour. (i) Luigi’s profit-maximizing output 5 plates an hour and economic profit is $18. Luigi’s maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In perfect competition, marginal revenue equals price, which is $24 a plate. Marginal cost is the change in total cost when output is increased by 1 plate an hour. The marginal cost of increasing output from 4 to 5 plates an hour is $22 ($102 minus $80). The marginal cost of increasing output from 5 to 6 plates an hour is $26 ($128 minus $102). So the marginal cost of the fifth plate is half-way between $22 and $26, which is $24. Marginal cost equals marginal revenue when Luigi produces 5 plates an hour. Economic profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals $120 ($24 multiplied by 5). Total cost is $102, so economic profit is $18. (ii) Luigi’s profit-maximizing output 4 plates an hour and economic profit is zero. Luigi’s maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. Marginal revenue equals price, which is $20 a plate. The marginal cost 4th plate an hour is $20. The profit-maximizing output is 4 plates an hour. PERFECT COMPETITION b. c. d. 5. a. b. c. d. e. f. 6. a. 273 Economic profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals $80 ($20 multiplied by 4). Total cost is $80, so economic profit is zero. (iii) Luigi’s profit-maximizing output is zero and economic profit is $14. Marginal revenue equals price, which is $12 a plate. The marginal cost is $12 if Luigi’s produces 2 plates an hour. If Luigi’s produces 2 plates an hour, total revenue is $24 ($12 multiplied by 2). Total cost is $48, so Luigi’s would incur an economic loss of $24 if she produces 2 plates. By shutting down, Luigi will incur a loss equal to total fixed costs, which are $14 (total cost when output is zero). Luigi’s shutdown point is at a price of $16 a plate. The shutdown point is the price that equals minimum average variable cost. To calculate total variable cost, subtract total fixed cost ($14, which is total cost at zero output) from total cost. Average variable cost equals total variable cost divided by the quantity produced. For example, the average variable cost of producing 3 plates is ($62 minus $14) divided by 3, which equals $16 a plate. Average variable cost is a minimum when marginal cost equals average variable cost. The marginal cost of producing 3 plates is $16. So the shutdown point is a price of $16 a plate. Luigi’s economic profit at the shutdown point is $14. At the shutdown point, total revenue is zero. Total variable cost is zero and so total cost equals total fixed cost , which is $14. Luigi’s incurs a loss of $14 at the shutdown point. Firms with costs identical to Luigi’s will enter at any price above $20 a plate. Firms will enter an industry in the long run when firms currently in the industry are making economic profit. Firms with costs identical to Luigi’s will make economic profit when the price exceeds minimum average total cost, which is $20 a plate. The market price is $8.40 a cassette. The market price is the price at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. The firm’s supply curve is the same as its marginal cost curve at prices above minimum average variable cost. Average variable cost is a minimum when marginal cost equals average variable cost. Marginal cost equals average variable cost at the quantity 250 cassettes a week. So the firm’s supply curve is the same as the marginal cost curve for the outputs equal to 250 cassettes or more. When the price is $8.40 a cassette, each firm produces 350 cassettes and the quantity supplied by the 1,000 firms is 350,000 cassettes a week. The quantity demanded at $8.40 is 350,000 a week. The industry output is 350,000 cassettes a week. Each firm produces 350 cassettes a week. Each firm incurs an economic loss of $581 a week. Each firm produces 350 cassettes at an average total cost of $10.06 a cassette. The firm can sell the 350 cassettes for $8.40 a cassette. The firm incurs a loss on each cassette of $1.66 and incurs an economic loss of $581a week. In the long run, some firms exit the industry because they are incurring economic losses. The number of firms in the long run is 750. In the long run, as firms exit the industry, the price rises. In long-run equilibrium, the price will equal the minimum average total cost. When output is 400 cassettes a week, marginal cost equals average total cost and average total cost is a minimum at $10 a cassette. In the long run, the price is $10 a cassette. Each firm remaining in the industry produces 400 cassettes a week. The quantity demanded at $10 a cassette is 300,000 a week. So the number of firms is 300,000 cassettes divided by 400 cassettes per firm, which is 750 firms. The market price is $8.40 a cassette. 274 CHAPTER 11 b. c. d. e. f. 7. a. b. c. d. e. f. 8. a. b. c. d. The market price is the price at which the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. The firm’s supply curve is the same as its marginal cost curve at prices above minimum average variable cost. Average variable cost is a minimum when marginal cost equals average variable cost. Marginal cost equals average variable cost at the quantity 250 cassettes a week. So the firm’s supply curve is the same as the marginal cost curve for the outputs equal to 250 cassettes or more. When the price is $8.40 a cassette, each firm produces 350 cassettes and the quantity supplied by the 1,000 firms is 350,000 cassettes a week. The quantity demanded at $8.40 is 350,000 a week. The industry output is 350,000 cassettes a week. Each firm produces 350 cassettes a week. Each firm incurs an economic loss of $1,561 a week. Each firm produces 350 cassettes at an average total cost of $12.86 a cassette. The firm can sell the 350 cassettes for $8.40 a cassette. The firm incurs a loss on each cassette of $4.46 and incurs an economic loss of $1,561a week. In the long run, some firms exit the industry because they are incurring economic losses. The number of firms in the long run is 500. In the long run, as firms exit the industry, the price rises. In long-run equilibrium, the price equals the minimum average total cost. When output is 450 cassettes a week, marginal cost equals average total cost and average total cost is a minimum at $12.40 a cassette. In the long run, the price is $12.40 a cassette. Each firm remaining in the industry produces 450 cassettes a week. The quantity demanded at $12.40 a cassette is 225,000 a week. So the number of firms is 225,000 cassettes divided by 450 cassettes per firm, which is 500 firms. The market price is $7.65 a cassette. When the price is $7.65 a cassette, each firm produces 300 cassettes and the quantity supplied by the 1,000 firms is 300,000 cassettes a week. The quantity demanded at $7.65 is 300,000 a week. The industry output is 300,000 cassettes a week. Each firm produces 300 cassettes a week. Each firm makes an economic loss of $834 a week. Each firm produces 300 cassettes at an average total cost of $10.43 a cassette. The firm can sell the 300 cassettes for $7.65 a cassette. The firm incurs a loss on each cassette of $2.78 and incurs an economic loss of $834 a week. In the long run, some firms exit the industry because they are incurring economic losses. The number of firms in the long run is 500. In the long run, as firms exit the industry, the price rises. Each firm remaining in the industry produces 400 cassettes a week. The quantity demanded at $10 a cassette is 200,000 a week. So the number of firms is 200,000 cassettes divide by 400 cassettes per firm, which is 500 firms. The market price is $7.65 a cassette. When the price is $7.65 a cassette, each firm produces 300 cassettes and the quantity supplied by the 1,000 firms is 300,000 cassettes a week. The quantity demanded at $7.65 is 300,000 a week. The industry output is 300,000 cassettes a week. Each firm produces 300 cassettes a week. Each firm incurs an economic loss of $1,815 a week. Each firm produces 300 cassettes at an average total cost of $13.70 a cassette. The firm can sell the 300 cassettes for $7.65 a cassette. The firm incurs a loss on each cassette of $6.05 and incurs an economic loss of $1,815 a week. PERFECT COMPETITION e. f. 275 In the long run, some firms exit the industry because they are incurring economic losses. The number of firms in the long run is 222. In the long run, as firms exit the industry, the price rises. In long-run equilibrium, the price will equal the minimum average total cost. When output is 450 cassettes a week, marginal cost equals average total cost and average total cost is a minimum at $12.40 a cassette. In the long run, the price is $12.40 a cassette. Each firm remaining in the industry produces 450 cassettes a week. The quantity demanded at $12.40 a cassette is approximately 100,000 a week. So the number of firms is 100,000 cassettes divided by 450 cassettes per firm, which is 222 firms. 276 CHAPTER 11 Additional Problems 1. 2. Bob’s is one of many burger stands along the beach. The figure shows Bob’s cost curves. a. If the market price of a burger is $4, what is Bob's profit-maximizing output? b. Calculate the profit that Bob's makes. c. With no change in demand or technology, how will the price change in the long run? Lucy’s Lasagna is a price taker that has the following costs: Output Total cost (plates per hour) (dollars per hour) a. 0 5 1 20 2 26 3 35 4 46 5 59 If lasagna sells for $7.50 a plate, what is Lucy’s profit-maximizing output? b. What is Lucy’s shutdown point? c. Over what price range will Lucy leave the lasagna industry? d. Over what price range will other firms with costs identical to Lucy’s enter the industry? e. What is the price of lasagna in the long run? PERFECT COMPETITION 277 Solutions to Additional Problems 1. a. b. c. 2. a. b. c. d. e. Bob’s profit-maximizing quantity is 200 burgers a day. Bob’s maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In perfect competition, marginal revenue equals price, which is $4 a burger. Marginal cost is $4 when 200 burgers a day are produced. Bob’s profit is $160 a day. Profit equals total revenue minus total cost. Total revenue equals $800 a day ($4 a burger multiplied by 200 burgers). The average total cost of producing 200 burgers is $3.20 a burger, so total cost equals $640 a day ($3.20 multiplied by 200 burgers). Profit equals $800 minus $640, which is $160 a day. The price will fall in the long run to $3 a burger. At a price of $4 a burger, firms make economic profit. In the long run, the economic profit will encourage new firms to enter the burger industry. As they do, the price will fall and economic profit will decrease. Firms will enter until economic profit is zero, which occurs when the price is $3 a burger (price equals minimum average total cost). Lucy’s profit-maximizing output is 2 plates an hour. Lucy’s maximizes its profit by producing the quantity at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost. In perfect competition, marginal revenue equals price, which is $7.50 a plate. Marginal cost is the change in total cost when output is increased by 1 plate an hour. The marginal cost of increasing output from 1 to 2 plates an hour is $6 ($26 minus $20). The marginal cost of increasing output from 2 to 3 plates an hour is $9 ($35 minus $26). So the marginal cost of the second plate is half-way between $6 and $9, which is $7.50. Marginal cost equals marginal revenue when Lucy produces 2 plates an hour. Lucy’s shutdown point is at a price of $10 a plate. The shutdown point is the price that equals minimum average variable cost. To calculate total variable cost, subtract total fixed cost ($5, which is total cost at zero output) from total cost. Average variable cost equals total variable cost divided by the quantity produced. For example, the average variable cost of producing 3 plates is $10 a plate. Average variable cost is a minimum when marginal cost equals average variable cost. The marginal cost of producing 3 plates is $10. So the shutdown point is a price of $10 a plate. Lucy will leave the industry if in the long run the price is less than $11 a plate. Lucy’s Lasagna will leave the industry if it incurs an economic loss in the long run. To incur an economic loss, the price will have to be below minimum average total cost. Average total cost equals total cost divided by the quantity produced. For example, the average total cost of producing 2 plates is $13 a plate. Average total cost is a minimum when it equals marginal cost. The average total cost of 3 plates is $11.67, and the average total cost of 4 plates is $11.50. Marginal cost when Lucy's produces 3 plates is $10 and marginal cost when Lucy's produces 4 plates is $12. At 3 plates, marginal cost is less than average total cost; at 4 plates, marginal cost exceeds average total cost. So minimum average total cost occurs between 3 and 4 plates—$11 at 3.5 plates an hour. Firms with costs identical to Lucy’s will enter at any price above $11 a plate. Firms will enter an industry when firms currently in the industry are making economic profit. Firms with costs identical to Lucy's will make economic profit when the price exceeds minimum average total cost, which is $11 a plate. The price in the long run is $11 a plate. This is the price that makes zero economic profit.