* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

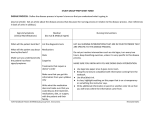

Download Algorithm for Treating Behavioral and Psychological

Moral treatment wikipedia , lookup

Psychiatric and mental health nursing wikipedia , lookup

Emergency psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Parkinson's disease wikipedia , lookup

Controversy surrounding psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

History of psychiatric institutions wikipedia , lookup

Mental status examination wikipedia , lookup

Glossary of psychiatry wikipedia , lookup

Antipsychotic wikipedia , lookup

Autism therapies wikipedia , lookup

Behavioral theories of depression wikipedia , lookup

Abnormal psychology wikipedia , lookup

Alzheimer's disease wikipedia , lookup