* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download New Prevention Technologies in the UK

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

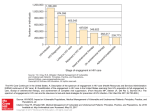

New Prevention Technologies in the UK A discussion paper to inform the seminar: HIV and biomedical prevention: re-framing the social science agenda. Prepared by Peter Keogh and Catherine Dodds Background New HIV Prevention Technologies (NPTs) can be defined as the application of pre-existing pharmaceutical treatments for HIV in novel ways to prevent HIV transmission. Four such applications can be identified: Treatment as Prevention (TasP), Pre-Exposure Prophylaxes (PrEP), Post-Exposure Prophylaxes (PEP) and Topical Microbicides. Treatment as Prevention (TasP) TasP consists of the treatment of a person with diagnosed HIV with anti-retrovirals in order to reduce viraema in fluids involved in sexual and other kinds of HIV exposure and transmission (seminal and vaginal fluids, blood and breastmilk). Hence the uninfected partner is exposed to much less or even no virus during unprotected or protected sexual intercourse as is the fetus/neonate during birth or breastfeeding. Treating to reduce infectiousness involves commencing HIV treatments prior to a decline in the individual’s clinical biomarkers before they are clinically indicated (that is, as soon as infection is identified rather than when the patient reaches a CD4 count of 250 cells/mm3 or less). Randomised control trials have found TasP to be highly effective. The HTPN052 trial found a 96% reduction in the risk of transmission amongst those who started treatment early rather than waiting until it was clinically indicated. Although clinicians and people with HIV have been aware of connections between viral load in blood and infectiousness for some time, until recently operationalizing this connection in terms of clinical practice was limited to the prevention of vertical transmission (that is treating treating women during preganancy and peripartum with the specific aim of preventing transmission to the child during birth) and clinical interventions in this respect were highly effective. However, WHO and UNAIDS now recommend the roll-out of TasP to all groups of people with HIV and their partners as part of integrated programmes of HIV prevention encompassing clinical, social and structural interventions to reduce HIV (called Treatment 2.0). In the UK, the British HIV Association (BHIVA) is currently preparing clinical guidance on the use of TasP, and this will undoubtedly aid the development of much-needed overarching clinical, patient and advocate consensus on how it should be rolled out. Recent BHIVA clinical guidance on treatment in general now recommends that all those with HIV infection accessing clinical services have a full informed discussion with their clinicians about the prevention aspects of treatment and that clinical care is informed by that discussion. Post and Pre-Exposure Prophylaxes (PEP and PrEP) PEP consists of course of antiretroviral treatment to prevent infection after (actual or suspected) exposure to HIV either sexually or occupationally. PEP has been available in the UK through GUM and many A&E departments for some years now and is dispensed according to risk assessment guidelines. PrEP is the use of antiretrovirals prior to exposure to HIV to prevent infection. PrEP is intended for use by people who may be at frequent risk for HIV or those in populations where there is a generalised epidemic. A series of studies conducted among MSM in six countries has shown that PrEP reduced infection by 44%. Moreover, clinicians in the UK are already prescribing PrEP for heterosexual sero-different couples wishing to conceive. In July 2012, the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of the drug Truvada for pre-exposure prophylactic purposes and in the UK, a feasibility study amongst MSM is now underway which will lead to the development of an implementation trial. Topical Microbicides Whilst PEP and PrEP are orally administered and hence systemic treatments, topical Microbicides refer to prototype topical applications (gels and sponges) that have been shown to be somewhat effective for vaginal use. Approval of these applications is being fast-tracked by the FDA and further trials for anal topical microbicides are underway. Background to this seminar New Prevention Technologies have generated intense interest amongst clinicians, the HIV community/activist sector and policy-makers. Whilst some have hailed NPTs as having the potential to ‘end the AIDS pandemic’ others are more circumspect both about the veracity/strength of the evidence of effectiveness and of the likely impact of NPTs on HIV transmission and acquisition. These reservations tend to focus on epidemiological factors (for example, that many new instances of exposure and transmission emanate from those most recently infected who have not yet had the opportunity to test for HIV) or on concerns about implementation and acceptability (for example, the range of psycho-social factors that will influence individuals’ capacity or willingness to engage with NPTs or use them effectively). That is, there is growing concern that NPTs are being considered solely as a clinical intervention where both effectiveness and the compliance of a largely passive population of people with or at risk for HIV are assumed. Moreover, NPTs are increasingly becoming the focus of moralistic or normative discourses about individual risk behaviours and responsibility (for example, ‘should’ PrEP be made widely available if it leads to increased risk-taking or sexual irresponsibility amongst MSM)? The purpose of this seminar is neither to promote nor undermine the implementation of NPTs. Rather this paper emerges out of a concern that the application of NPTs in the UK and the development of policy and guidance are taking place in the absence of input from the social sciences and, with some notable exceptions from medical sociology. The purpose of this paper is to inform and generate discussion for this event. The paper explores what we think are the main areas of enquiry for the social sciences and indicates the kinds of roles that social scientists might play in the development of NPTs in the UK. We are mindful of the need to bring together social scientists from a range of backgrounds and formations: cultural sociologists, health service researchers, economic sociologists, demographers, policy analysts, social epidemiologists and those with expertise in complex evaluations. Hence we have organised the material presented in this paper under five headings that range from questions of individual identity to how we might go about designing complex evaluations for NPTs. The questions therein are tentative and speculative and we look forward to having a much more developed output as a result of the event. Self, Identity & Personal Narrative Much work has been done on the different ways in which HIV (and other conditions) interact with notions of self and identity. Over the course of the epidemic, sociologists have described the emergence of novel identities in relation to HIV and the ways in which individuals engage in ‘identity work’ to articulate personal and communal responses to the epidemic. These notions of self reinforce or undermine over-arching social and cultural norms. Thus, we can describe selves that are sick/healthy, responsible/irresponsible, resisting/complying, moral/immoral etc. and thus articulate the lived experience of ‘being’ HIV-Positive or HIV-Negative in ever more complex ways. We can also identify events, milestones or narratives that are transformative in people’s biographical construction of themselves. These might include instances of sexual risk, testing for HIV, diagnosis with HIV, periods of and recovery from illness, changes in diagnostic or prognostic markers (such as viral load or CD4 count), starting treatments, treatment failure etc. NPTs have the potential to disrupt such identities and personal narratives. For example, by requiring both those diagnosed HIV positive and those receiving a negative diagnosis to engage with and take pharmacological treatments, PrEP has the potential to disrupt established distinctions between sick and healthy, HIV Positive and HIV Negative etc. Moreover, the status and place of key events in personal narratives (such as an HIV test or commencing treatment) change as individuals test for different reasons and take various actions depending on the result. Finally, the question of wherein lies the moral self or the responsible self becomes more complex as we consider targeting PrEP and TasP to those at greatest risk through their sexual behaviours and relationships. For example, choosing or refusing to take treatments and sub-optimal adherence to treatment is likely to take on a moral dimension as viral suppression is linked with potential for HIV transmission on an individual level. Will those who do not adhere be judged differently now that they are seen to potentially increase the risk of infection for their sexual partners? We must also be mindful of the potential for NPTs to interact with the self as inscribed within overarching social categories and systems. We know that HIV epidemiology is stratified by gender, ethnicity, social class and sexual identity. This is due in part to factors associated with the biology of HIV transmission but also reflective of broader social and power inequities in society. NPTs offer the potential for individuals to take far greater control of transmission risk and hence reduce their own vulnerability. This is particularly the case for women engaging in heterosexual sex. Whilst attending to the impacts that NPTs are likely to have on women, groups of gay men etc., we should also attend to the potential for NPTs to be introduced as solely clinical interventions without regard for preexisting power and social inequality. Thus, how might NPT implementation be mediated by pre-existing structural inequality and how might NPTs be transformative of structural inequality through shifting the means of control of sexual risk? Intimacy, Risk and Sex Medical Sociologists and others have described the ways in which HIV and the imperative to engage with sexual risk (or the eschewing of that imperative) have been both reductive and productive in informing the intimate lives of people with HIV, those close to them and those at risk. The management of HIV risk has defined the parameters of intimate relationships and intimate futures for many as expressed by sexual and reproductive decision-making etc. Moreover, individuals, couples and groups have forged novel intimate and sexual lives in the face of HIV. The ways in which we have constructed and produced knowledge about sexual risk has also changed throughout the epidemic. We have moved from a language of propensity to risk-taking in individuals or groups or notions of riskavoidance to a conception that sexual HIV risk involves individuals who are more or less competent, more or less practiced at negotiating highly personal and protean ‘landscapes of risk’. Thus the conception of sexual risk has moved from a reductive or deficit model to one that characterises the negotiation of sexual HIV risk as productive in terms of the self and the types of relationships open to people with HIV, those close to them and those at risk. The landscapes of risk described will be altered by NPTs. Individuals will have additional factors to weigh up when it comes to calibrating their sexual risk practices (such as the infectiousness of their partner if they are not themselves infected or whether their partner is on PrEP if they are infected). In addition, the ways in which intimacy is managed within the context of HIV is likely to be transformed. For example, sero-different relationships may become more tenable, sustainable and desirable as the balance of responsibility (and the associated tensions) for avoiding infection shifts tangibly: both partners possibly taking anti-retrovirals and the couple engaging with the clinic together using clinical markers to negotiate their intimate risk. This is likely to lead to an opening up of the potentiality of sex and relationships making more fulfilling sex and conception without transmission easier and allowing individuals and couples a much greater sense of control over their own future and their future as part of an intimate relationship. Finally, there may be changes in the way that we produce knowledge about risk and intimacy. Technologies that increase complexity around risk and promote the agency of those living with that risk promise to move us further away from positivist or deficit models of risk. However, as they also herald far greater involvement of the clinical sciences in both the measurement of risk and in measuring the impact of these technologies on behaviour, we may see a resurgence of research utilising positivist models of risk. Communities, Resistance and Activism As identities and moral/ethical perspectives shift, so too will the lines along which individuals and communities resist or collude with powerful defining discourses (for example medicalizing discourses or shaming discourses such as stigma). NPTs imply that people’s experience of and relationship with the virus and the clinic will change. More and more people who have received a negative HIV diagnosis will find themselves the subjects of medical interventions akin to those who have been diagnosed positive and the burden of risk management within couples may become more evenly distributed. As the identities/self-concept of ‘HIV Positive’ and ‘HIV Negative’ become blurred or lose their definitional power so too will they alter in terms of their collective, political and cultural meanings. Such meanings have been highly instrumental in defining interest groups united by common experiences and aims (for example, people with HIV, gay men/MSM, African communities) and determining how groups have chosen to organise themselves to attain political ends. Although community will retain a social and political currency, their make-up and the alliances/dis-alliances within and between them are likely to change as are the aims, targets and approaches of AIDS activism. NPTs would also appear to be already having an impact on the relationships between the different actors in HIV treatment and prevention (for example, AIDS activists, treatment advocates, community and voluntary organisations, drugs companies, clinical providers and governments). For example, lines between treatment activism/advocacy and HIV prevention are blurring whilst clinical providers are becoming increasingly involved in HIV prevention implementation. Meanwhile, enthusiasm with regard to the potential benefits of NPTs may not be shared by government or communities and there are likely to be a range of different perceptions. Thus, we may see re-alignments between and within groups and challenges to consensus emerging over the coming years. These may bring into play many concerns some of which are already apparent: for example, human rights concerns regarding compulsion to comply with treatments, concerns that clinical and treatment decisions might be made with reference to cost rather than clinical need and concerns about the re-emergence of moralistic discourses around ‘responsible’ or ‘irresponsible’, ‘undeserving’ or ‘deserving’, ‘innocent’ or ‘guilty’ people with HIV. Systems, Structures and Institutions It is essential to take account of the interrelated structures and institutions involved in the conceptualisation and delivery of NPTs in the UK. Already, many such institutions (such as clinics and voluntary agencies) are collaborating in ways that are likely to streamline systemic access to NPTs, primarily through integration within existing prevention and treatment interventions. Inevitably, there will also be (and no doubt, already have been) a range of institutions and systems - for cultural, disciplinary, pragmatic, resourcing and territorial reasons – that conflict, and will obfuscate or delay the progress of the NPT agenda. Those involved in the study of health systems delivery, organisational sociology, and policy analysis will find opportunities to ask a range of questions about the shifts, tensions and breakthroughs that impact how NPTs are conceptualised, managed and delivered at a systems level. Furthermore, such matters can only be understood within the broader context of the most severe cuts to public funding in a generation, accompanied by an overhaul of England’s National Health Service and shifting responsibilities for the delivery and oversight of public health. As a result, considerable pressure is placed on those tasked with planning and implementation to demonstrate value in all areas of health delivery, making it additionally difficult to envisage how an entirely new and costly layer of HIV treatment provision will merge in to the sweeping changes to English NHS structures which are already well underway. With regard to implementation analysis, work will need to be undertaken to better understand the knowledge, attitude and skill capacities and requirements for those providing interventions to encourage NPT uptake. Furthermore, there are already clear indications in high-income countries with concentrated epidemics, that the initial waves of NPT policy and clinical guidance implementation will encourage the targeting of particular patient groups who are most likely to benefit from and sustain adherence. Adequate understanding of the dynamics of implementation of such guidance will require, for example, analyses of consultant and patient interactions that incorporate theoretical understandings of power relations via social stratification. The extent to which stigmatising processes are enacted within such interactions will also be a potential area of interest. It has already been apparent in the production of evidence around NPTs, their application and licensing that key moments function as drivers. The Swiss Statement of 2008, the publication of HTPN 052 data in 2011 followed by the Rome IAS Conference, the iPrex study results and the US Food and Drug Administration’s licensing of Truvada as PrEP in 2012 are all examples of these key moments. In each instance, the movement towards widespread NPT implementation looks increasingly inevitable. However, perhaps less well-known are the key moments and scientific results that fail to support this momentum. Where evidence of NPT efficacy has been equivocal, or models of rollout suggest a rather lack-lustre epidemiological impact, there are some questions to be asked about the attention that such findings receive. It is likely that those with an interest in Science and Technology Studies may be best placed to examine how and why evidence is alternatively exploited and ignored, by whom, and to what end. There are further considerations about the potential human rights implications of NPTs that may be overlooked. With the emergence of new prevention options, it is possible that the meanings and associations traditionally ascribed to HIV may be further re-framed. There is a potential, for instance, to re-consider the collective protections that widespread treatment access can afford entire populations (not just those who are already infected). This framing would stand in considerable contrast to the highly individualised and stigmatised perceptions of the pre-ARV epidemic. The ways in which systems, institutions and structures utilise such a re-framing will also be an interesting area of study (continuing the work of those who have already examined the altered systemic responses to the epidemic in light of the introduction of ARVs post-1996). Already, arguments about the widespread public health benefits of TasP have convinced the government in England to remove charges for HIV treatment for those who do not have access to public funds. It would be interesting for health policy analysts to examine the way in which this public health argument shifted what had appeared to be an intransigent government policy that had been immune to more than a decade of human rights advocacy campaigns. Economic considerations and analyses As described above, the considerable economic and organisational shifts taking place in the NHS provide a crucial backdrop to the narratives of NPT provision in the UK in the coming decade. There is little question that the infrastructure and pharmaceutical costs required to widely implement NPT policies are an issue of pressing concern for those who are at the forefront of clinical delivery. At this point it is difficult to know how the National Commissioning Board for the NHS in England (which will assume responsibility for the commissioning of HIV care and treatment) will regard calls for considerable resourcing for preventive outcomes (which they may well consider to be beyond their remit), but prospective mapping and spending models could allow us to foresee the terrain ahead. There are considerable economic and resourcing implications beyond the provision of the pharmaceutical interventions themselves. For instance, where treatment is given to people with diagnosed HIV as a means of reducing their infectiousness, regular monitoring of patients’ CD4 counts and viral loads (usually quarterly) is essential for patients to be able to make informed choices about their involvement in potential HIV exposure activities. However, in many local areas, healthcare providers are cutting back on the frequency of routine visits and blood tests, due to the heavy resource implications that these have. Feasibility studies related to routine HIV clinic visits, transferring of routine HIV care to primary care physicians, and the potential for self-administered CD4 and VL tests (like diabetes self-test kits) will assist with the broader understanding of the economic implications of routinised self-care. With the current circumstance of healthcare spending instability, it is also difficult to be certain that a course of treatment (including TasP) that is prescribed for an individual will be one that is economically sustained over the longer term. Currently, in London, patients with HIV are being asked to consider switching to a less expensive treatment regime due to local fiscal decisions. Where such changes are being made to treatment protocols in general, it is feasible that such issues may arise in future with TasP protocols as well. There are therefore a considerable number of ethical questions to be asked about the potential impacts of treatment plans that lack financial sustainability. NPT clinical guideline development will inevitably seek to collate cost effectiveness evidence within the NHS context. It is therefore prescient for social scientists to start framing the types of questions that such evaluations should seek to answer. There is an array of allied services that will compose NPT delivery, from HIV testing, to diagnostics to engagement with clinical services to treatment – evaluations will need to consider the systemic costs and benefits, rather than simply considering treatment costs in isolation. In addition to this, such evaluations will need to take into account the various investments that are required at each stage along the patient trajectory, taking into account the considerable drop-out rates that are known to occur at each stage. Evaluation, outcomes and experiments One of the distinct challenges that have limited the evaluation of programmes of behavioural HIV prevention in the UK (comprising a raft of intersecting interventions) is a lack of agreed complex intervention evaluation methods, starting with indicators of success formulated through a consensus process. This situation has been exacerbated by the conflicting definitions of appropriate outcome indicators that arise between biomedical and social science disciplines, with the former favouring clinical markers, and the latter interim measures such as changes in knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. Prior to embarking on process evaluations and outcome evaluations of NPTs, robust discussions about appropriate indicators of success are essential. There are already a range of promising approaches that help to foreshadow programmes of NPTs research that will enable a better collective understanding of NPTs efficacy, effectiveness, impact and delivery. The work of the HIV Modelling Consortium considers the starting points for a better understanding and interpretation of the complex relationships between NPTs, HIV prevention behavioural interventions, and behavioural change. At this stage in the development and potential implementation of NPTs, we are likely to be collectively reliant upon the work of mathematical modellers, who can test a range of potential hypotheses and implementation variables. It is clear that with improved collaboration between a range of social scientists, clinicians and modellers increasingly reliable variables can be selected for use. In this way, it can be assured that the best possible models (which are most aligned with real world conditions, rather than optimum conditions) are the ones that proceed. In the longer term, and given the research funding environment in the UK, we are likely to be reliant also on naturalistic experimental approaches when designing complex evaluations of NPTs. The question becomes how we balance naturalistic evaluations with the imperative to design and resource more traditional experimental implementation trials (such as randomised control trials) taking into account the not inconsiderable ethical, resource and methodological challenges thrown up by such approaches. Finally, as alluded to in prior sections, a policy analysis approach that incorporates the methods used by those in science and technology studies and the sociology of knowledge will also be essential in order to better understand how and why particular research findings are widely known and counted as ‘evidence’ of effectiveness, while others are not. Brief Conclusion The topics covered in this paper and the ways that questions have been framed reflect the interests and perspectives of the the authors. As such, these questions should be seen as tentative and the accounts contained herein as necessarily partial. However, it is hoped that this paper fulfils two basic purposes. First that it demonstrates the multiplicity and complexity of questions raised for social scientists by the emergence and implementation of NPTs in the UK and second that it triggers reflection and debate for the upcoming seminar.