* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 3 - Studyit

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

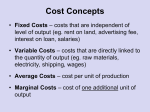

Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms 3.1 - MICROECONOMICS 1 - Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Utility As people consume goods or services, they gain satisfaction. Utility is a measure of that satisfaction. Marginal utility - Changes or additions to total utility, resulting from the consumption of an additional good or service. Total utility - The aggregate satisfaction gained from consuming successive quantities of a good or service. The Law of Marginal Utility - Marginal utility typically decreases as consumption increases. For example, a can of coke. If you are very thirsty, you will appreciate the first drink a lot. As you drink more and more cans of coke, the added satisfaction you get is less as you get less and less thirstier. It gets to the point where there is no marginal utility; therefore total utility is at its maximum. Quantity 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 Utility Schedule for cola Marginal Utility 10 9 7 2 0 -2 Total Utility 0 10 19 26 28 28 26 Optimum Purchase rule The optimum purchase rule - Satisfaction is maximised. Marginal Utility will be zero. Price will equal Marginal Utility. As Total Utility is increasing, Marginal Utility is positive. As Total Utility is decreasing, Marginal Utility is negative. When Total Utility is at its maximum, Marginal Utility is zero, demonstrating the optimum purchase rule. By convention, plot Marginal Utility midway between the numbers. For example, if units consumed are 4, plot it at 3.5. 1 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms The individual demand curve is derived from their Marginal Utility curve. 1. Consumers gain less extra satisfaction from each extra unit of consumption. They are willing to pay less for the next unit of consumption until P=MU. They will only buy a small quantity when price is high and vice versa. 2. When the price of a good increases, it increases relative to substitutes (whose prices stay constant), therefore fewer consumers will demand the good as they are buying substitutes instead. This is known as the substitution effect. 3. When price goes up, people can afford to buy less of the good (income effect). Equimarginal rule: Is all income spent? Yes MUa = MUb Pa Pb Do nothing because the consumer is in equilibrium MUa > MUb Pa Pb Spend more on good a, because MU per dollar is higher, so the MU per dollar will drop. Spend less on good b, because MU per dollar is lower, so the MU per dollar will rise. No Spend more on both goods as you must spend all your income Some Examples: 1. Income is $200 Good A: 15 units are bought at $6 each. Marginal Utility is 30. Good B: 10 units are bought at $11 each. Marginal Utility is 55. Has all $200 been spent? 15 x $6 + 10 x $11 = $200. Yes. Is the consumer in equilibrium? 30/6 = 55/11 → 5 = 5. Yes. Therefore they should do nothing. 2. Income is $220 Good A: 15 units are bought at $6 each. Marginal Utility is 30. Good B: 10 units are bought at $11 each. Marginal Utility is 55. Has all $220 been spent? 15 x $6 + 10 x $11 = $200. No. Therefore they should spend more on both goods. 3. Income is $50. Good A: 20 units are bought at $1 each. Marginal Utility is 8. Good B: 15 units are bought at $2 each. Marginal Utility is 12. Has all $50 been spent? 20 x $1 + 15 x $2 = $50. Yes. Is the consumer in equilibrium? 8/1 ≠ 12/2 → 8 ≠ 6. No. Therefore more should be spent on Good A and less should be spent on Good B. If asked for the order of which a consumer will buy something, look at the marginal utility per dollar. The highest marginal utility per dollar will be purchased first, then the next highest and so on until they have spent all their money. 2 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Market Structures Feature Perfect Monopolisti c Imperfect Oligopoly Duopoly Monopoly Imperfect Imperfect Imperfect Two firms only One firm only Differentiate d Very Strong One product only Very Very Very Strong Very Strong Price Maker Strong Type of competitio n Number of sellers Perfect Lots Many small firms Type of product Barriers to entry Control over price Control over quantity sold How do firms compete? Demand curve New Zealand Example Homogenou s (identical) None Differentiated Weak A few large firms dominate Differentiate d Strong None Weak Price Maker None Weak Limited Strong Price Maker Limited Unable Price and non-price competition Elastic Non Price competition Non Price competition No competition Kinked Inelastic Retail shops Oil companies Banks Vodafone and Telecom Perfectly inelastic NZ Post, Personalise d Plates Perfectly Elastic Dairy farmers Vegetable growers Monopsony is a single buyer. Barriers to entry include high capital costs for formation and many regulations. Perfect competitors are so insignificant that they have to accept the price that is prevailing on the market. If they set the price too low, they will lose out on profits. If they set the price too high, no one will buy from them and they will have to close down. A monopolist cannot control price and quantity at the same time. It can control only one at a time. The market will control the other. For example, if they raise price, the market will determine the quantity sold. 3 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Strategies that firms use The common goal of all firms is profit maximisation. They may include sales maximisation (making as many sales as possible) so that they establish themselves in the market, gain market share or gain market power. Satisficing is a goal where firms set up a sales or profit target than can be achieved with ease. Price competition Discounts Buy one get one free Having sales (e.g. end of season, clearance, stocktaking or closing down sale) Interest free terms Trade ins Undercutting a competitors price A price war (other firms use the same tactics by lowering their price. In the end, the firm’s market share will remain largely unchanged) Non Price Competition Packaging Giveaways (different product) Competition Sponsorship Location Modifications 24 hour service advertising Advantage to producers: Reduces the likelihood of price wars while their sales and market share still increase. Disadvantage to producers: Costs increase to provide these extras. Advantage to consumers: Better quality of goods and services and greater choice. Disadvantage to consumers: Price increases (because of increased costs) and they may buy the product for the wrong reasons. 4 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Revenue Curves - Perfect competition Output 1 2 3 4 5 Price ($) 10 10 10 10 10 Total Revenue 10 20 30 40 50 Average Revenue 10 10 10 10 10 Marginal Revenue 10 10 10 10 10 Total Revenue: Price times Quantity (P x Q) Average Revenue: Total Revenue divided by Quantity (P ÷ Q) Marginal Revenue: Change in Total Revenue. Marginal Revenue is the additions to Total Revenue made as each extra unit of output is sold. Price is the same as Average Revenue (mathematically this is correct). Since the price is constant and the firms have to accept the price on the market, Average Revenue will equal Marginal Revenue. Price will equal the demand curve because the market determines the price. 5 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Revenue Curves - Imperfect competition Output 1 2 3 4 5 Price ($) 10 8 6 4 2 Total Revenue 10 16 18 16 10 Average Revenue 10 8 6 4 2 Marginal Revenue 10 6 2 -2 -6 When Output increases, Price decreases and vice versa. When Total Revenue is at its maximum, Marginal Revenue is zero. It is illogical to sell past the point where Marginal Revenue equals zero as Total Revenue decreases as more quantities are sold. Marginal Revenue is always less than Total Revenue. If Marginal Revenue and Average Revenue are different, it is imperfect competition (if they are the same, it is perfect competition). Marginal Revenue intersects the x axis halfway of the intersection of Average Revenue and the x axis. A firm’s demand curve is the Average Revenue curve. 6 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Accounting Costs The actual (or explicit) costs involved in production, for example, mortgage, rent, power, wages and raw materials. Economic Costs The accounting costs plus opportunity costs. For example, the lost salary if a teacher sets up a lawn mowing business or lost interest that could have been earned if the owner invested the funds in the bank instead of a business. Decisions of a firm Firms try to use resources efficiently. If some industries are declining, resources will be switched. The supply curve is related to cost as an increase in costs causes a shift to the left. Cost Curves Output Fixed Costs Variable Costs Total Costs Average Costs Marginal Costs 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 250 70 120 140 160 190 230 280 350 440 540 660 800 960 250 320 370 390 410 440 480 530 660 690 790 910 1050 1210 320 185 130 102.5 88 80 75.71 75 76.67 79 82.73 87.5 93.08 70 50 20 20 30 40 50 70 90 100 120 140 160 Average Variable Costs 70 60 46.67 40 38 38.33 40 43.75 48.89 54 60 66.67 73.85 Average Fixed Costs 250 125 83.33 62.15 50 41.67 35.71 31.25 27.78 25 22.73 20.83 19.23 Fixed Costs - Do not change no matter how much is produced, e.g. rent. Variable Costs - The more you produce, the more these costs will be. These are the costs that change when output changes. Total Costs - Fixed Costs plus Variable Costs. Average Cost - Total costs divided by output (similar to average revenue) or Average Variable Costs plus Average Fixed Costs. Marginal Cost - The additional cost when each extra output is produced. Average Variable Costs - Variable costs divided by output. Average Fixed Costs - Fixed Costs divided by output. 7 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Average Fixed Cost Curve This is because the cost is fixed. Average Fixed Cost gets less and less because it is spread over a greater amount of outputs. Average Fixed Cost Curve/Average Variable Cost Curve/Average Cost Curve The Average Variable Cost curve decreases first as firms make better use of resources. Then as output rises, resources are used inefficiently. Technical optimum output occurs at the minimum point of AC. Resources are effectively combined. As output increases, the AVC and AC curves get closer together because AFC + AVC = AC, and AFC is decreasing. Adding in the Marginal Cost Curve The Marginal Cost Curve initially decreases because of efficient use of resources and increasing returns. Eventually diminishing returns will occur therefore the Marginal Cost curve will increase. The Marginal Cost Curve intersects the AVC and AC curves at their minimum points. This is because the Marginal Cost Curve is less than AVC and AC when they are decreasing and the Marginal Cost Curve is more the AVC and AC when they are increasing. This is because Marginal Costs are the additions to costs as output increases. MC is the supply curve above AVC. Variable Cost Curve/Total Cost Curve/Fixed Cost Curve The vertical gap between the Total Cost Curve and the Variable Cost Curve is Fixed Costs because FC + VC = TC. 8 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms The size of a firms operation Short Run REMEMBER: Short run is concerned about an input/factor, not inputs/factors. Diminishing returns is the idea that as more and more of a factor is used, with at least one fixed factor; there is some point at which the increase in output will be at a decreasing rate. Firms will experience diminishing returns in the short run because at least one factor is fixed. If additions of other factors are added into the production process, the total output will increase at a diminishing rate (marginal product must eventually fall). This is because each factor has less of the fixed factor to work with, reducing its ability to produce extra output. Diminishing returns sets in when the firm’s marginal costs increase because as each extra variable unit produces less when diminishing returns are occurring. Therefore the production of extra units of output will require more and more of variable inputs to produce them compared with earlier units. For example, when given a table like this: Output 10 100 250 Machines/Workers 1 2 3 Add another row with marginal output: Marginal Output 10 90 150 Therefore after the 4th machine, diminishing returns sets in OR: With the 5th machine, diminishing returns sets in. 450 4 550 5 200 100 Increasing returns to a factor reflect that a firm’s short run average costs are falling. Inputs ↑5% Inputs ↓10% ↑Returns to ↓Costs ↑Marginal Efficient Outputs ↑10% Outputs ↓5% a factor output Decreasing returns to a factor reflect that a firm’s short run average costs are rising. Inputs ↑10% Inputs ↓5% ↓Returns to ↑Costs ↓Marginal Inefficient Outputs ↑5% Outputs ↓10% a factor output Long Run REMEMBER: Long run is concerned about inputs/factors, not an input/factor. In the long run, factors are variable because the firm is more adaptable to change. Economies of scale (increasing returns to factors) may be due to existing or new machinery being more efficiently utilised. Fixed costs are spread over more units pulling down long run average costs. Buying in bulk may result in discounts. Inputs ↑5% Inputs ↓10% Economies ↓Costs ↑Marginal Efficient Outputs ↑10% Outputs ↓5% of scale/ output ↑Returns to factors Diseconomies of scale (decreasing returns to factors) may be because of expansion in a firm’s operation resulting in less efficient use of resources. Inputs ↑10% Inputs ↓5% Diseconomies ↑Costs ↓Marginal Inefficient Outputs ↑5% Outputs ↓10% of scale/ output ↓Returns to factors 9 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Short Run and Long Run SAC 1: Short run Average Cost curve for machine 1 SAC 2: Short run Average Cost curve for machine 2 etc etc. LRAC: Long run Average Cost curve A: ↓Costs, returns to a factor are increasing and the firm is efficient. B: ↓Costs, returns to factors are increasing (economies of scale) and the firm is efficient. C: ↑Costs, returns to a factor are decreasing and the firm is inefficient. D: ↑Costs, returns to factors are decreasing (diseconomies of scale) and the firm is inefficient. 10 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Break-even Break-even is when revenue covers all economic costs; i.e. AR=AC (AC=AFC+AVC). The preferred point is to be operating at Break-even or higher. The Break-even point occurs at the minimum point of AC. This is because all costs are covered, therefore there is no loss. For example: AFC AVC AR Loss 50 40 90 0 Shutdown Shutdown is when revenue just covers variable costs. The Shutdown point occurs at the minimum point of AVC. Firms will not be willing to supply anything below this point as they will be making a greater loss compared to what they will lose if they shut down. This is why the supply curve is generated by the MC curve above AVC. Quantity Supplied at a price below the minimum point of AVC will always be zero. Firms will still operate between break-even and shut down point because they are still covering a part of their fixed costs. Therefore they will lose less if they continue to operate compared to the loss they will make if they shut down. For example: If a firm chooses to continue operating: AFC AVC AR Loss 50 40 50 40 If a firm chooses to shut down: AFC AVC AR Loss 50 0 0 50 Therefore if they continue to operate, they will lose only $40 instead of $50 if they shut down. 11 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Accounting Profit In accounting, profit is Revenue (Income) minus actual costs (expenses). The costs are the actual (explicit) costs involved. Therefore a profit in accounting is made when actual income is greater than expenses. For example: A teacher quits their job and sets up a lawn mowing business. The teacher got paid $50,000 salary. The income from the lawn mowing business is $120,000 and expenses were $40,000. They also had $50,000 worth of savings in a bank account with a 7% interest rate. The accounting profit will be: Income 120,000 Less Expenses 40,000 Accounting Profit $80,000 Economic Profit In economics, profit is Revenue (Income) minus total costs. The costs are actual (explicit) costs plus opportunity (implicit) costs. Economic profit is less than Accounting profit. Economic costs are greater than Accounting costs. For the example above: Income 120,000 Less Expenses 40,000 Less lost salary 50,000 Loss lost interest 3,500 (7% of $50,000) Economic Profit $26,500 Maximising Profit If the firm is able to make a profit, their goal is to maximise that profit. To maximise their profit, they would operate at point Q. Beyond Q’, the firm would be making a loss. Minimising a loss If a firm is unable to make a profit at all, the goal is to minimise their loss. To minimise a loss, they will operate at point Q. At any other point there will be a greater loss. 12 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Marginal Analysis Determining output For perfect and imperfect competition the Equilibrium output position is where MC = MR. Note MC must cut MR from below (if MC and MR intersect twice). This is because you are either maximising your profits or minimising your losses. If you produce at a level less than this point, you are not maximising your profits as you are losing out on potential profits. Therefore you should increase output. If you produce at a level higher than this point, you are not minimising your losses as you are losing money for each extra unit of output. Therefore you should decrease output. Price is when Output intersects the Average Revenue Curve. 13 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Supernormal Profit Supernormal Profit is when a return is more than sufficient to keep an entrepreneur in their present activity. At MR = MC, AR>AC. Supernormal Profit is shaded in blue below. Subnormal Profit Subnormal Profit is when a return is insufficient to keep an entrepreneur in their present activity. At MR = MC, AR<AC. Subnormal Profit is shaded in blue below. Normal Profit Normal Profit is when a return is sufficient to keep an entrepreneur in their present activity. All costs including opportunity costs of production are fully covered. AR = AC. 14 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms The long run for a monopoly A monopoly prefers to operate at their profit maximising position where MC = MR. This position is called mark up pricing. A monopoly restricts quantity by deliberately charging a higher price compared to what would happen in perfect competition. This results in a deadweight loss. Deadweight loss is a loss of welfare to individuals or society which is not offset by a welfare gain to some other individual or group. It is not transferred anywhere else but just disappears from the system. Deadweight loss occurs when equilibrium cannot be achieved because of the high prices charged. Deadweight loss is shaded in blue. Because of the fact that monopolies have high barriers to entry, the government can regulate a monopoly by the administering of price to control the ill effects of monopoly organisation in the market. They can regulate the price to P2/Q2. This is where MC = AR (i.e. the demand curve intersects with the supply curve). This is called the Social Optimum, Marginal Cost Pricing or Allocative Efficiency. This is where consumers are very happy. They can also further regulate prices to P3/Q3. This is where AC = AR (i.e. normal profits) and the firm is breaking even. 15 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms The long run for a perfect competitor In the short run a perfect competitor will earn supernormal, normal or subnormal profits. In the long run a perfect competitor will earn normal profits (At MR = MC, AR = AC). This is because if firms are operating at supernormal profit, since there are no barriers to entry, more people will set up businesses in that industry to try and get the high profits. Therefore the supply for the whole industry increases shifting the market supply curve to the right. This decreases price for the whole industry. Since the market determines the price for perfect competitors, price will decrease for individual firms to where AR = AC which are normal profits. On the flip side, if a firm is operating at a subnormal profit in the long run they will shut down because of the losses they are making. Therefore market supply will decrease, shifting the supply curve for the industry to the left, raising price to where MC = MR and AC = AR, which are normal profits. It will remain at normal profits, because if more firms enter, they will increase supply to the industry, decreasing price and therefore they would earn subnormal profit. No firms would exit either because they are happy as they are breaking even. 16 Microeconomics 3.1 Marginal analysis and behaviour of firms Demand shifting in the long run for perfect competition If demand increases in the market, the demand curve shifts to the right. This increases the price. Because resources are now more scarce, costs increase and the individual firm’s supply curve (i.e. the MC curve above minimum AVC) shifts to the left. If they keep operating at Q1, MC2 is greater than MR2. Therefore to reduce marginal costs and to maximise profit, the firm must decrease production to Q2 where MC2 = MR2 to maximise profit. This can happen in reverse if demand in the market decreases. 17