* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Measuring the US Economy

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

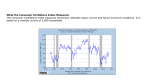

FIN 30220: Macroeconomics Measuring the US Economy The Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) reports Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for the United States on a quarterly basis: For the first quarter of 2017, GDP in the United States was (on an annualized basis) was... $19,027,000,000,000.00 * Source: www.bea.gov GDP is the standard benchmark for economic well being. Is it a good indicator of well being? VS Ratio 1950: $275B 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 2016: $18,675B GDP 1950: $2,200B 1950: $15,000 1950: $16,000 2016: $16,727B 2016: $51,549 2016: $30,240 Real GDP 2009 Dollars Real Per Capita GDP 2009 Dollars Real Median Income 2015 Dollars GDP is the standard benchmark for economic well being. Is it a good indicator of well being? VS Annual defense spending has grown from $35B in 1950 to $732 B in 2017. Should this be subtracted out? The service industry has grown from 28M employees in 1950 to 126 M in 2017. Is this really “new activity”? Should we count things like pollution as economic “bads”? How do we account for the added quality and convenience of new products and technologies? The Genuine progress indicator, or GPI, is a metric that has been suggested to replace, or supplement, gross domestic product (GDP) as a measure of economic growth. GPI is designed to take fuller account of the health of a nation's economy by incorporating environmental and social factors which are not measured by GDP. *Source: Rethinking Progress The Satisfaction with Life Index was created by Adrian G. White, an analytic social psychologist at the University of Leicester, using data from a metastudy. It is an attempt to show life satisfaction in different nations. Denmark 273 (#1) 143 (#167) 237 (#41) 246.7 (#23) 206 (#90) 210 (#82) 230 (#51) 180 (#152) 210 (#81) 243 (#26) 100 (#170) Burundi Note: North Korea Didn’t Participate In another study, called “The Joy Index”, we have the following results: Country Ranking Joy Index Score (Perfect Score = 100) #1: China 100 #2 North Korea 98 #3 Cuba 93 #4 Iran 88 #5 Venezuela 85 #152 South Korea 18 #203 (Last Place) United States 3 *The Joy Index was constructed by “researchers” from North Korea's Chosun Central Television Station. To understand how to measure GDP, we need to understand the US economy. We need to visualize how goods, services, and payments flow between sectors of the economy. Households supply labor and capital to firms Factor Markets Firms Households Product Markets Firms supply households with final goods The Basic circular flow – real goods and services Every flow of real goods and services is matched by an equal flow of payments in the opposite direction Firms pay wages, interest, profits Factor Markets Households supply labor and capital to firms Firms Firms supply households with final goods Product Markets Households Pay for goods and services Households Let’s leave out the flow of real goods for simplicity…the basic circular flow is payments from households to firms (payment for final goods and services) and from firms to households (payment for factor services). However, keep in mind that there has to be an equal flow in the opposite direction of real goods and services. Factor Markets Households Firms Product Markets Borrowing and stock issues by firms Now, we can add the financial sector (acting as a middleman between businesses and firms) Financial Markets Net Household savings Factor Markets Households Firms Investment spending Product Markets Now, add the public sector Financial Markets Government Borrowing Factor Markets Taxes Households Transfers Firms Product Markets Government Spending Government Now, add rest of the world Financial Markets Foreign Borrowing Foreign Lending Factor Markets Households Firms Product Markets Government Rest of World Exports Imports Let’s begin by valuing production. We are calculating GDP, so we only need to worry about production taking place in the United States. Biggest Issue: Double Counting Firm A produces raw cotton and sells it to firm B for $1,000 Firms Production (GDP) Product Markets Firm B coverts the raw cotton to yarn and sells it to firm C for $1,500 Firm C coverts the yarn into sweaters and sells them to the consumer for $2,500 $1,000 + $1,500 + $2,500 = $5,000 Is there really $5,000 worth of production? Of course not! Option #1: Avoid Double Counting By Measuring Value Value Added Firm A produces raw cotton and sells it to firm B for $1,000 $1,000 (Not really, but we need to start somewhere!) Firm B coverts the raw cotton to yarn and sells it to firm C for $1,500 Firm C coverts the yarn into sweaters and sells them to the consumer for $2,500 $500 + $1,000 $2,500 Example: GDP Calculation (Value Added) Suppose that Intel produces 1,000 computer chips (P = $100) 1000 Chips sold to Dell 1,000 computer chips @ $100 $100,000 1,000 computers @ $2,000 $2,000,000 Materials Expense GDP Dell produces 1000 computers (P = $2,000) - $100,000 $2,000,000 Example with Inventories GDP Calculation (Value Added) Suppose that Intel produces 1,000 computer chips (P = $100) 1,000 computer chips @ $100 $100,000 500 computers @ $2,000 $1,000,000 1000 Chips sold to Dell Materials Expense Inventory Investment Dell produces 500 computers (P = $2,000) Dell has 500 chips remaining in inventories GDP - $100,000 $50,000 $1,050,000 Example with capital equipment GDP Calculation (Value Added) Suppose that Xerox produces 50 copiers (P = $5000) 50 copiers @ $5000 $250,000 50 Copiers sold to Dell 1,000 computers @ $2,000 $2,000,000 Equipment expense - $250,000 Equipment Investment $250,000 Dell produces 1000 computers (P = $2,000) GDP $2,250,000 GDP Calculation GDP 1,500 computer chips @ $100 $150,000 50 copiers @ $5000 $250,000 1,000 computers @ $2,000 $2,000,000 Material Expenses - $355,000 Equipment Investment $225,000 Inventory Investment $30,000 $2,300,000 Note: This is the full value of the equipment purchased. If I used the depreciated value, I would be calculating Net Domestic Product (Let’s Assume 10% depreciation) GDP Depreciation NDP $2,300,000 -$22,500 $2,277,500 In July 2013, the BEA announced a change in methodology… Expenditures for research and development (R&D) and for entertainment, literary, and artistic originals have many of the characteristics of other fixed assets…. Thus, expenditures on the production of these types of intangible assets, or intellectual property, be treated as fixed investment. GDP figures were revised to take into account the new treatment all the way back to 1929 Real Gross Domestic Product. The revision added approximately $800B to GDP in 2017. All together… Suppose that Intel produces 1,500 computer chips (P = $100) 200 Chips bought by households GDP Calculation Suppose that Xerox produces 50 copiers (P = $5000) 1,300 Chips Bought by Dell 45 Copiers Bought by Dell Dell Produces 1,000 Computers (P = $2,000) – sold to consumers Leaves 300 Chips in inventories 5 Copiers bought by households GDP 1,500 computer chips @ $100 $150,000 50 copiers @ $5000 $250,000 1,000 computers @ $2,000 $2,000,000 Material Expenses - $355,000 Equipment Investment $225,000 Inventory Investment $30,000 $2,300,000 Gross Value Added By Sector: 2017Q1 Category Business Households & Institutions Government GDP Amount (B) $14,350 $2,430 $2,247* $19,027 % of Total 75% 13% 12% 100% *Equals compensation of general government employees plus general government consumption of fixed capital. Option #2: Avoid Double Counting By Measuring Expenditures of End User Purchases Firm A produces raw cotton and sells it to firm B for $1,000 $0 (Not really, but we need to start somewhere!) Firm B coverts the raw cotton to yarn and sells it to firm C for $1,500 Firm C coverts the yarn into sweaters and sells them to the consumer for $2,500 $0 + $2,500 $2,500 Each good or service produced must be matched by an equal expenditure Households Firms Government Product Markets Exports GDP C I G NX G Rest of World Imports EX IM Let’s recalculate using expenditures Suppose that Intel produces 1,500 computer chips (P = $100) GDP Calculation Suppose that Xerox produces 50 copiers (P = $5000) Equipment Investment $225,000 Inventory Investment $30,000 1,000 Computers @ $2,000 200 Chips bought by households 1,300 Chips Bought by Dell 45 Copiers Bought by Dell Dell Produces 1,000 Computers (P = $2,000) – sold to consumers Leaves 300 Chips in inventories 5 Copiers bought by households GDP $2,000,000 200 Chips @$100 $20,000 5 Copiers @$5,000 $25,000 $2,300,000 The GDP report comes out during the last week of every month and gives a breakdown by expenditure category GDP: 2017Q1 Category Amount (B) % of Total Consumption $13,108 69% Gross Investment $3,149 17% Government $3,328 17% Net Exports GDP -$558 $19,027 -3% 100% GDP: 2017Q1 Consumption Expenditures Goods GDP C I G NX G $13,108B $4,219B Investment Expenditures Fixed Investment $3,149B $3,147B Durable $1,439B Non-Residential $2,396B Non-Durable $2,780B Structures $537B $8,889B Equipment $1,074B Services Intellectual Property Let’s take a closer look at consumption and investment Residential Change in Inventories $785B $751B $2B We can use this identity to “decompose” economic growth GDP C I G EX IM G IG C G EX IM G %GDP % C % I % G % EX %IM GDP GDP GDP GDP GDP Category 2017Q1 % of Total Growth (Real) Contribution to Real GDP Growth Consumption $13,108 69% 0.6% .44% Gross Investment $3,149 17% 4.8% .79% Government $3,328 17% -1.1% -.19% Net Exports -$558 -3% --- .13% Exports $2,314 12% 5.8% .70 Imports $2,872 15% 3.8% .57 $19,027 100% GDP 1.2% GDP: 2017Q1 GDP C I G NX G Real Growth Consumption Expenditures Goods 0.6% 0.3% Real Growth Investment Expenditures Fixed Investment 4.8% 11.9% Durable -1.4% Non-Residential 11.4% Non-Durable 1.2% Structures 28.4% 0.8% Equipment 7.2% Intellectual Property 6.7% Services Let’s take a closer look at consumption and investment Residential Change in Inventories 13.8% $4.3B GDP: 2017Q1 Consumption Expenditures GDP C I G NX G Contribution to GDP Growth Investment Expenditures Contribution to GDP Growth 0.07% Non-Residential 1.35% Durable -0.11% Structures 0.69% Non-Durable 0.18% Equipment 0.39% 0.37% Intellectual Property 0.27% Goods Services Total 0.44% Let’s take a closer look at consumption and investment Residential 0.50% Change in Inventories -1.07% Total 0.78% Option #3: Avoid Double Counting By Measuring Income Earned Income Earned Firm A produces raw cotton and sells it to firm B for $1,000. Profits are $1,000 • $600 Paid to Workers • $400 Paid to Owners Firm B coverts the raw cotton to yarn and sells it to firm C for $1,500. Profits are $500 • $200 Paid to Workers • $300 Paid to Owners Firm C coverts the yarn into sweaters and sells them to the consumer for $2,500. Profits are $1,000 • $800 Paid to workers • $200 Paid to owners $1,000 (Not really, but we need to start somewhere!) $500 + $1,000 $2,500 GDP Calculation Suppose that Intel produces 1,500 computer chips (P = $100) Wages: $50,000 Suppose that Xerox produces 50 copiers (P = $5000) $150,000 Profits: $100,000 Wages: $200,000 $250,000 Profits: $50,000 Wages: $900,000 200 Chips bought by households 1,300 Chips Bought by Dell 45 Copiers Bought by Dell Dell Produces 1,000 Computers (P = $2,000) – sold to consumers Leaves 300 Chips in inventories $1,900,000 Profits: $1,000,000 5 Copiers bought by households GDP $2,300,000 To get to income earned by Americans, we need to account for American production taking place abroad and foreign production within the US Nike began manufacturing sport shoes and apparel in Thailand in 1980. Currently Nike has 84 contract factories employing 75,000 people and producing $500M annually. In 1992, BMW built a production facility in Spartanburg, South Carolina – it employs 10,000 people and produced 297,326 units in 2013 (approx. $13B). Gross Domestic Product vs. Gross National Product Nike • Sales: $500M • Value Added: $200M $50M Paid to Foreign labor $10M paid to American labor $40M paid to foreign investors $100M paid to American investors BMW • Sales: $13B • Value Added: $5B $3B paid to American labor $1B paid to Foreign labor $400M paid to US investors $600M Paid to foreign investors GDP GDP $5B BMW’s output was produced inside the US $0 Nike’s output was produced outside the US $5B Gross Domestic Product vs. Gross National Product Nike • Sales: $500M • Value Added: $200M $50M Paid to Foreign labor $10M paid to American labor $40M paid to foreign investors $100M paid to American investors BMW • Sales: $13B • Value Added: $5B $3B paid to American labor $1B paid to Foreign labor $400M paid to US investors $600M Paid to foreign investors $3B $400M GNP $10M $100M GNP $3.51B Paid as wages to US citizens Paid as profits to US investors Paid as wages to US citizens Paid as profits to US investors GDP Alternatively…. GDP BMW • Sales: $13B • Value Added: $5B $3B paid to American labor $1B paid to Foreign labor $400M paid to US investors $600M Paid to foreign investors Nike • Sales: $500M • Value Added: $200M $50M Paid to Foreign labor $10M paid to American labor $40M paid to foreign investors $100M paid to American investors + + - BMW’s output was produced inside the US $0 Nike’s output was produced outside the US $5B $10M paid to American labor $100M paid to American investors $1B paid to Foreign labor $600M paid to Foreign investors GNP GNP = GDP + Net Factor Payments (NFP) $5B Income earned by Americans abroad Income earned by foreigners in the US $3.51B Income earned by Foreigners in the US Income by Americans in the US Factor Markets Income earned by Americans abroad 2017Q1 Households Firms NDP Net Domestic Product = GDP - Depreciation GDP + Net Factor Payments - Depreciation - Statistical Discrepancy National Income $19,027 $ 237 $ 2,975 -$ 130 $16,419 National Income by Source: 2017Q1 Category Amount(B) % of Total Compensation of Employees $10,267 63% Proprietor’s Income $1,458 9% Rental Income $736 4% Corporate Profits $2,110 13% Net Interest and Misc. $481 3% Indirect Taxes (Sales Tax and Tariffs) $1,264 Less Subsidies $59 Labor Share of Income Capital Share of Income 7% Surplus of Government Enterprises -$22 Net Business Transfers $184 1% National Income $16,419 100% Financial Markets Personal Income = Outlays NI C S T National Income Households Firms Product Markets Government Every dollar earned income has to be spent Personal Income to Personal Savings: 2017Q1 (Billions) Personal Income Less Personal Taxes Equal Personal Disposable Income Less Personal Outlays $16,330 $1,995 $14,335 $13,590 Consumption Expenditures $13,108 Interest Payments $284 Personal Transfers $198 Equals Personal Savings $747 Personal Savings as % of Disposable Income 5.2% This number includes healthcare payments made by Medicare/Medicaid SO, this number includes 401k/pension plan contributions Personal Savings Rate in the US Side Note China: 25% India: 21% S. Korea: 21% Thailand: 14% 16 % if Disposable Income 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 Let’s apply “Output equals Income” to the GDP equals expenditures identity GDP C I G NX NFP NFP G GNP C I G CA DEP DEP N NI C I G CA G I N I G DEP Output equals expenditures CA NX NFP Now, let’s apply “Income equals Outlays” NI C I G CA T T N NI T C I G T CA C C N S I G T CA N Government Deficit Flow of Funds Financial Markets Foreign Borrowing Lastly, we have an accounting identity for the financial markets known as the flow of funds Foreign Lending Households Firms Government S I G T CA Rest of World N Also, every dollar that is saved is borrowed Gross Savings Net Savings $3,390 $445 Domestic Business $628 Personal Savings $699 Government Savings -$883 Consumption of Fixed Capital GPS I G G T CA Net Household Lending Net Savings: $699 + Consumption of Fixed Capital: $502 - Gross Investment: $760 $441 $2,945 Net Business Lending Domestic Business $1,912 Households $502 Net Savings: $630 + Consumption of Fixed Capital: $1,912 - Gross Investment: $2,341 Government $530 Gross Investment $201 $3,724 Net Government Lending Private (Household And Business) $2,341 Household $760 Net Savings: -$883 + Consumption of Fixed Capital: $530 - Gross Investment: $623 Government $623 -$976 Note: Statistical Discrepancy = -$143 US Current Account Balance (0.7% of GDP) $47-B 100 0 1947 1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 2012 Billions of Dollars -100 -200 -300 -400 -$479B (-2% of GDP) -500 -600 -700 -800 -900 -$859B (-6% of GDP) We can analyze this using the “Income Equals Outlays” Identity…. CA NI C I G N Total US Income We are living beyond our means! Total US Spending Or, we can analyze this using the “Flow of Funds” Identity…. S I G T CA G We are borrowing more that we are saving! Public Borrowing Private Borrowing Household Saving In other words, the US is borrowing over $1B per day from abroad! Should we be worried about this? Personal Savings/Net Lending By Households 1200 * The Difference between personal savings and net lending by households is gross investment by households Billions of Dollars 1000 800 600 400 200 0 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 -200 -400 Household Net Lending Personal Savings 2000 2005 2010 2015 Net Lending By Households/Business 1200 1000 Billions of Dollars 800 600 400 200 0 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 -200 -400 -600 -800 Households Business 1995 2000 2005 2010 2015 Net Lending By Households/Business/Government Billions of Dollars 1000 500 0 1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985 1990 1995 -500 -1000 CA S I G T G -1500 -2000 Government Households Business 2000 2005 2010 2015 Lets take a look at the US economy from 1947 to 2016 … 20000 $18,860B (2016Q4) 18000 16000 Billions of Dollars 14000 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 $243.1B (1947Q1) 0 1947 1954 1961 1968 1975 1982 Average Annual Growth 1989 1996 2003 2010 ln 18,860 ln 243.1 *100 6.31% 69 However, remember the problem we ran into with the movie grosses. GDP (current market value of goods and services produced) isn’t really the same in 1947 as it is in 2014 because the dollar has lost a lot of its value (i.e. prices have gone up) 1947 Car: $1,500 Gasoline: 23 cents/gal House: $13,000 Bread: 12 cents/loaf Milk: 80 cents/gal Postage Stamp: 3 cents 2017 Car: $33,560 Gasoline: 2.27 dollars/gal House: $234,000 Bread: $1.98 dollars/loaf Milk: 3.98 dollars/gal Postage Stamp: 49 cents We need to construct a “price index” to represent and average of prices over a wide variety of products. How do we do this? The objective of a price index is to measure cost of living. To state this precisely, a price index measures the dollar cost of obtaining a fixed level of utility (happiness). Suppose at the current prices, you elect to buy 3 slices of pizza and 2 beers The absolute dollar cost of your current happiness is (2)($3.50) + (3)($2.00) = $13 Example: $3.50 $2.00 As prices change, we keep the quantities of each good constant (guaranteeing a constant level of utility) Good Base Year Price (BY) Base Year Quantity Current Year Price (CY) Inflation Beer $3.50 2 $4.50 25% Pizza $2 3 $2.20 10% (2)($4.50) + (3)($2.20) = $15.60 ln 15.60 ln 13 *100 18% Alternatively, we could write the price index in terms of relative dollars (relative to a base year) instead of absolute dollars (this is how its actually calculated). Good Base Year Price (BY) Base Year Quantity Current Year Price (CY) Inflation Beer $3.50 2 $4.50 25% Pizza $2 3 $2.20 10% Base Year Expenditure: (2)($3.50) + (3)($2.00) = $13 Beer Expenditure Share: (2)($3.50)/$13 =.54 Pizza Expenditure Share: (3)($2)/$13 = .46 3.50 2.00 PBY .54 .46 1.0 3.50 2.00 (Or, 100) 4.50 2.20 PCY .54 .46 1.2 3.50 2.00 (Or, 120) ln 120 ln 100 *100 18% The CPI is calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) on a monthly basis Personal Care 4% Consumer Price Index Tobacco & Smoking Products 1% Food & Beverage 16% Education & Communication 5% Housing 40% Recreation 6% The CPI is composed of 211 individual products over 38 geographic areas (8,018 total prices). Medical 6% Transportation 17% Apparel 5% When Calculating the Consumer Price Index, the expenditure shares remain constant!!! Good Base Year Price (1983) Year 2015 Price Year 2016 Price Housing $200 $780 $800 Transportation $90 $280 $300 Food $40 $190 $200 Apparel $30 $245 $250 200 90 40 30 CPI1983 .40 .30 .20 .10 1 200 90 40 30 Household Budget ( or, 100 ) 780 280 190 245 CPI 2015 .40 .30 .20 .10 4.25 200 90 40 30 Or, 425 800 300 200 250 CPI 2016 .40 .30 .20 .10 4.43 200 90 40 30 ( or, 443 ) Average CPI inflation ln 443 ln 100 *100 4.50% 33 CPI inflation (2015 – 2016) ln 4.43 ln 4.25 *100 4.15% The Consumer Price Index (1948 – 2016) 16 300 CPI 12 10 250 200 8 6 150 4 100 2 0 1948 -2 1956 1964 1972 1980 1988 -4 2004 2012 50 0 1983 = 100 Average Inflation = 3.54% 1996 CPI CPI Inflation Rate 14 Note that expenditure shares do change over time, so the weights need to be updated periodically Expenditure shares in the CPI were last updated in 2013-14 Potential problem #1: Products change over time. Suppose you observe the following TV Prices 2003 2004 Price: $250 Features: 27 inch Cathode Ray Tube Enhanced Definition TV S-Video Input Universal Remote Price: $1,250 Features: 42 inch Plasma High Definition TV S-Video Input Universal Remote $1, 250 $250 *100 400% $250 Note: The first plasma TV was released by Fijitsu 1n 1995. The 42’’ TV cost $14,999 Is this a fair assessment of inflation? Solution: Hedonic Price Adjusting Price: $250 Features: 27 inch Cathode Ray Tube Enhanced Definition TV S-Video Input Universal Remote These three featured are estimated to be worth $100 Price: $1,250 Features: 42 inch Plasma High Definition TV S-Video Input Universal Remote These three featured are estimated to be worth $1000 Hedonically Adjusted price = $1,250 – ($1,000 -$100) = $350 Solution: Hedonic Price Adjusting Around a third of the CPI is Hedonically Adjusted Item Relative Importance Men’s Suits, Sport coats and Outerwear .113 Men’s Shirts and Sweaters .207 Men’s Pant’s and Shorts .160 Boy’s Apparel .188 Women’s Outerwear .114 Women’s Dresses .154 Women’s Suits and Separates .604 Girl’s Apparel .204 Men’s Footwear .216 Boy’s and Girl’s Footwear .169 Educational Books and Supplies .195 Major Appliances .159 Televisions .161 Other Video Equipment .030 Rent of Primary Residence 29.483 Total = 32.165% Potential Problem #2: What about housing? Consider the following examples Option #1: Rent a $240,000 house $1,000/mo. Option #2: Buy a $240,000 house with an interest only mortgage (5% per year) $240,000(.05) = $12,000/yr. = $1,000/mo. Option #3: Buy a $240,000 house with a 30 year mortgage (5% per year) $1,288/mo. Potential Problem #2: What about housing? Consider the following examples Option #3: Buy a $240,000 house with a 30 year mortgage (5% per year) Option #1: Rent a $240,000 house OR Option #2: Buy a $240,000 house with an interest only mortgage (5% per year) $1,288/mo. $1,000/mo. Difference = $288/mo. What if you put $288/mo. and put it in a savings account that earns 5% per year? Potential Problem #2: What about housing? Consider the following examples Option #1: Rent a $240,000 house OR Option #2: Buy a $240,000 house with an interest only mortgage (5% per year) Option #3: Buy a $240,000 house with a 30 year mortgage (5% per year) $1,000/mo. (This is pure cost of living) $1,288/mo. (This is cost of living plus investment in an asset) Solution: In 1983, the BLS decided to focus entirely on rental markets for housing. Housing Prices Housing Inflation 400.0 15 350.0 300.0 10 250.0 200.0 5 150.0 0 1976 100.0 50.0 1986 1991 1996 2001 -5 0.0 1976 1981 1981 1986 1991 Home Price Index Average Inflation Rate Home Price Index: 4.40% Rental Index: 4.01% 1996 2001 2006 Rental Price Index 2011 -10 Home Price Rental Price Can you spot the housing bubble? 2006 2011 Potential Problem #3: Substitution Recall that at the original prices, you elected to buy 3 slices of pizza and 2 beers The cost of your happiness at the initial prices is $3.50 (2)($3.50) + (3)($2.00) = $13 $2.00 Good Base Year Price (BY) Current Year Price (CY) Inflation Beer $3.50 $4.50 25% Pizza $2 $2.20 10% (1)($4.50) + (4)($2.20) = $13.30 If beer increases in price to $4.50 (25% increase) and pizza increases to $2.20 (10% increase), suppose you alter your decision and buy 1 beer and 4 slices of pizza ln 13.30 ln 13 *100 2.2% Original Expenditure: (2)($3.50) + (3)($2.00) = $13 Good Base Year Price (BY) Current Year Price (CY) Inflation Beer $3.50 $4.50 25% Pizza $2 $2.20 10% No Substitution: Substitution: (2)($4.50) + (3)($2.20) = $15.60 (1)($4.50) + (4)($2.20) = $13.30 ln 15.60 ln 13 *100 18% ln 13.30 ln 13 *100 2.2% Which measure of inflation is more realistic? Solution: In 2000, the BLS introduced a “chain weighted CPI” that allows for this substitution between different goods. It’s thought to be a better gauge of inflation. Expenditure shares in the Chain CPI are updated every two years. 6.0 160.000 CCPI 5.0 120.000 3.0 100.000 2.0 80.000 1.0 60.000 0.0 1999 -1.0 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 40.000 -2.0 20.000 -3.0 0.000 Chained CPI Inflation Rate 4.0 140.000 It is, however, very controversial… Average Inflation Rate CPI: 2.31% CCPI: 2.06% 6 5 Inflation Rate 4 3 2 1 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 -1 -2 -3 CPI CCPI 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 Example: Suppose that you are a social security recipient. Let’s calculate your total payments received in social security payments under the different inflation measures from 2000 to 2016. (Assume you received the average social security payment of $1,180 per month in 2000) CPI Inflation Rate (2.31% per year) $14,160 $14,160 1.0231 $14,160 1.0231 ... $14,160 1.0231 $290, 784 2 16 CCPI Inflation Rate (2.06% Per Year) $14,160 $14,160 1.0206 $14,160 1.0206 ... $14,160 1.0206 $284, 787 2 16 Difference = $5,997 ($352/yr.) Now, consider that there are approximately 65 million social security recipients: $5,997*65M = $390B ($23B/yr.) An alternative to the consumer price index is the GDP Deflator. Suppose we have the following Data Good Production (2014) Current Price (2014) Current Value Housing 300 $550 $165,000 Transportation 500 $350 $175,000 Food 100 $260 $26,000 Apparel 200 $220 $44,000 Total = GDP (Current Dollars) $410,000 Now, Suppose we revalue current GDP at, say, prices in 2009 (Call this the base year) Good Production (2014) 2009 Price 2009 Value Housing 300 $500 $150,000 Transportation 500 $300 $150,000 Food 100 $200 $20,000 Apparel 200 $200 $40,000 Total = GDP (2009 Dollars) $360,000 We can use these two numbers to construct an implied relative price Current value of current production (2014) Base year value of current production (Base year = 2009) $410,000 (Current Dollars) $360,000 (2009 Dollars) $410,000 (Current Dollars) $360,000 (2009 Dollars) Note that the base year (2009) is 1 (or, 100) by definition ln 114 ln 100 *100 2.62% 5 = 1.14 (or, 114) It turns out that the deflator is still a weighted average of individual relative prices Good Production (2014) 2009 Price 2009 Value 2014 Price Housing 300 $500 $150,000 $550 Transportation 500 $300 $150,000 $350 Food 100 $200 $20,000 $260 Apparel 200 $200 $40,000 $220 Total = GDP (2009 Prices) Housing Share of Real GDP $150, 000 $360, 000 .41 $360,000 Transp. Share of Real GDP $150, 000 $360, 000 .41 Food Share of Real GDP $20, 000 $360, 000 .06 Apparel Share of Real GDP $40, 000 $360, 000 .12 With the implied weights, you can calculate the GDP deflator in a similar fashion as the CPI $550 $350 $260 $220 P .41 .41 .06 .12 1.14 $500 $300 $200 $200 (Or, 114) Suppose we repeat for a different year to calculate an inflation rate Good Production (2013) 2009 Price 2013 Price Housing 280 $500 $535 Transportation 490 $300 $310 Food 105 $200 $240 Apparel 170 $200 Value of GDP at 2013 Prices $363,620 $342,000 $216 = 1.06 (or, 106) Value of GDP at 2009 Prices Housing Share of Real GDP $140, 000 $342, 000 .41 Transp. Share of Real GDP $147, 000 $342, 000 .43 Food Share of Real GDP $21, 000 $342, 000 .06 Apparel Share of Real GDP $34, 000 $342, 000 .10 $535 $310 $240 $216 P .41 .43 .06 .10 1.06 $500 $300 $200 $200 Index Inflation ln 114 ln 106 *100 7.27% (Or, 106) Now, the inflation rate incorporates price changes as well as expenditure share changes – a lot like the chained CPI! Good 2013 Price 2014 Price Inflation Housing $535 $550 2.76% Transportation $310 $350 12.10% Food $240 $260 8.00% Apparel $216 $220 1.83% 2013 Housing Share of Real GDP $140, 000 $342, 000 .41 Transp. Share of Real GDP $147, 000 $342, 000 .43 Food Share of Real GDP $21, 000 $342, 000 .06 Apparel Share of Real GDP $34, 000 $342, 000 .10 2014 Housing Share of Real GDP $150, 000 $360, 000 .41 Transp. Share of Real GDP $150, 000 $360, 000 .41 Food Share of Real GDP $20, 000 $360, 000 .06 Apparel Share of Real GDP $40, 000 $360, 000 .12 Average Inflation: 3.20% The GDP Deflator: 1948 - 2014 12 120 GDP Def. 10 100 80 6 4 60 2 40 0 1948 -2 -4 1960 1972 1984 1996 2008 20 2009 = 100 0 GDP Deflator Inflation Rate 8 A comparison between the CPI (Fixed Weight Index) and the GDP Deflator (Variable Weight Index) Good Production (2000) Price (2000) Production (2015) Price (2015) Apples 350 $25 400 $30 Oranges 250 $50 600 $55 Note the large expansion of the orange industry Inflation Rate For Apples ln $30 ln $25 *100 18.2% Inflation Rate For Oranges ln $55 ln $50 *100 9.5% Any price index should produce an inflation rate between 9.5% and 18.2% Good Production (2000) Price (2000) Production (2015) Price (2015) Apples 350 $25 400 $30 Oranges 250 $50 600 $55 Let’s assume an economy where there is only a consumption sector…. GDP C (Production shares equal consumption shares) Let’s make the base year 2000 GDP2000 350 $25 250 $50 $8750 $12,500 $21, 250 Apple expenditure share A $8, 750 .41 $21, 250 Orange expenditure share O $12,500 .59 $21, 250 Base Year Expenditure Shares A comparison between the CPI (Fixed Weight Index) and the GDP Deflator (Variable Weight Index) Good Production (2000) Price (2000) Production (2015) Price (2015) Apples 350 $25 400 $30 Oranges 250 $50 600 $55 ln $30 ln $25 *100 18.2% ln $55 ln $50 *100 9.5% Consumer Price Index (CPI) $25 $50 CPI 2000 .41 .59 1 $25 $50 $30 $55 CPI 2015 .41 .59 1.141 $25 $50 Remember…the expenditure shares are held constant at the base year’s expenditure shares CPI Inflation Rate ln 1.141 ln 1 *100 13.2% Good Production (2000) Price (2000) Production (2015) Price (2015) Apples 350 $25 400 $30 Oranges 250 $50 600 $55 GDP Deflator (DEF) GDP2000 350 $25 250 $50 $8750 $12,500 $21, 250 RGDP2000 350 $25 250 $50 $8750 $12,500 $21, 250 $21, 250 DEF2000 1 $21, 250 GDP2015 400 $30 600 $55 $12, 000 $33, 000 $45, 000 RGDP2015 400 $25 600 $50 $10, 000 $30, 000 $40, 000 $45, 000 DEF2015 1.125 $40, 000 GDP Deflator Inflation Rate ln 1.125 ln 1 *100 11.8% Good Production (2000) Price (2000) Production (2015) Price (2015) Apples 350 $25 400 $30 Oranges 250 $50 600 $55 Inflation Rate For Apples Inflation Rate For Oranges ln $30 ln $25 *100 18.2% ln $55 ln $50 *100 9.5% CPI Inflation Rate GDP Deflator Inflation Rate ln 1.141 ln 1 *100 13.2% ln 1.125 ln 1 *100 11.8% Why the discrepancy? Good Production (2000) Price (2000) Production (2015) Price (2015) Apples 350 $25 400 $30 Oranges 250 $50 600 $55 GDP Deflator (DEF) Implied Weights RGDP2000 350 $25 250 $50 $8750 $12,500 $21, 250 A2000 $8, 750 .41 $21, 250 A2000 $12,500 .59 $21, 250 $25 $50 DEF2000 .41 .59 1 $25 $50 RGDP2015 400 $25 600 $50 $10, 000 $30, 000 $40, 000 $10, 000 A2015 .25 $40, 000 $30, 000 O2015 .75 $40, 000 $30 $55 DEF2015 .25 .75 1.125 $25 $50 The GDP deflator is a variable weight index…the weights (which are actually production shares) fluctuate!! Good Production (2000) Price (2000) Production (2015) Price (2015) Apples 350 $25 400 $30 Oranges 250 $50 600 $55 Inflation Rate For Apples Inflation Rate For Oranges ln $30 ln $25 *100 18.2% ln $55 ln $50 *100 9.5% CPI Inflation Rate ln 1.141 ln 1 *100 13.2% GDP Deflator Inflation Rate ln 1.125 ln 1 *100 11.8% A2000 .41 A2000 .59 A2000 .41 A2000 .59 A2015 .41 A2015 .59 A2015 .25 A2015 .75 As oranges production grows relative to apples (most likely because they are becoming relatively cheaper), the GDP deflator increases the weight of oranges while the CPI keeps the weight fixed. Average Inflation Inflation with the GDP Deflator versus the CPI CPI: 3.55% GDP Def.: 3.20% 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 1948-01-01 1958-01-01 1968-01-01 1978-01-01 1988-01-01 1998-01-01 2008-01-01 -2 Let’s enlarge this area -4 CPI GDP Deflator Inflation with the GDP Deflator versus the CPI Average Inflation What’s going on here? CPI: 2.30% GDP Deflator: 2.01% 6 5 4 3 2 1 0 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 -1 -2 CPI GDP DEF 2011 2013 6 4 2 0 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 -2 CPI GDP DEF 80 60 40 20 0 -20 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 -40 -60 -80 -100 Oil Price Inflation Recall that a large portion of our oil is imported and is therefore not a part of GDP. Which means its not a part of the GDP deflator! The “core CPI” removes food and energy prices due to their excessive volatility. Average Inflation CPI: 2.30% Chain CPI: 2.06% GDP Deflator: 2.01% Core CPI: 1.95% So, what is inflation in the US currently? Price Index Current Value Annualized Current Value Year on Year CPI (December) .3% (per month) 3.6% 2.07% Core CPI (December) .2% (per month) 2.4% 2.15% Chained CPI (December) 0.07% (per month) 0.78% 2.02% PCE Index (December) .15% (Per Month) 1.8% 1.78% Implicit GDP Deflator 0.525% (Per quarter) 2.1% 1.65% AVERAGE 2.12% So, by current methodologies, we are around 2% per year. 1.93% Preferred measure for the Fed Pre 1990 Methodologies = 5.5% Pre 1990 Methodologies = 2% But, is inflation really 2%? Pre 1980 Methodologies = 10% Current Methodologies = 2% Source: Shadowstats.com Lets take a look at the US economy from 1947 to 2017 … 20000 $19,027B (2017Q1) 18000 16000 Billions of Dollars 14000 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 $243.1B (1947Q1) 0 1947 1952 1957 Average Annual Growth 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 ln 19,027 ln 243.1 *100 6.2% 70 2007 2012 2017 Lets use the consumer price index to adjust these nominal values to reflect year 2000 prices 20000 $19,027B 2017Q1 Billions of Dollars 18000 16000 14000 170.1 $19,027 $13,258 244.1 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 $243.1B (1947Q1) 2000 0 1947 170.1 $243.1 $1,905.6 21.7 1954 1961 1968 1975 1982 1989 Average Annual Real Growth 1996 2000 2003 2010 2017 ln 13,258 ln 1,905.6 *100 2.7% 70 Now, looking at real GDP over the last 67 years, we should see two basic features in the data 14000 $13,258B 2017Q1 Billions of 2000 Dollars 12000 10000 $1,905.6B (1947Q1) 1) The US economy grows over time 2) The US doesn’t grow at a constant rate 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 1947 1954 1961 1968 1975 1982 1989 1996 2003 2010 2017 Side Note: If we are measuring inflation incorrectly, we are also measuring real GDP incorrectly Real GDP Using the Current GDP Deflator Methodology Year 2000 = 100 Real GDP Using the Current GDP Deflator Methodology Year 2000 = 100 Source: Shadowstats.com Here’s an exaggerated view of what we are talking about GDP “Business Cycle” (deviations from trend) Trend (Average growth) Time The business cycle is a repeated pattern of recessions followed by recoveries Recession (Below Trend Growth) Recovery (Above Trend Growth) GDP Trend (Average growth) Peak Peak Trough Time How do we best describe long run growth in the US – Linear Trend 14000 Number of Quarters from 1947Q1 Billions of 2000 Dollars 12000 Trend 41.4 x 973.4 $10,412.6B 10000 The economy grows by $41.4B per quarter 8000 6000 4000 2000 973.4 0 1947 1954 1961 1968 1975 1982 1989 1996 2003 2010 2017 2004Q1 (228 Quarters) Trend 41.4228 973.4 10,412.6 How do we best describe long run growth in the US – Exponential Trend 18000 Number of Quarters from 1947Q1 Billions of 2000 Dollars 16000 14000 12000 Trend 2,236e.0069 x The economy grows by .69% per quarter 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 973.4 0 1947 1954 1961 1968 1975 1982 1989 1996 2003 2010 2017 2004Q1 (228 Quarters) Trend 2,236e.0069 228 10,782.1 An exponential trend assumes that the US has some constant annual rate of real economic growth (~3% per year). Note that actual growth varies even over long time periods. 5 Annual Growth Rate 4 Average Real Growth = 3% 3 2 Current Real Growth 1 1950's 1960's 1970's 1980's 1990's 2000's Actually, it looks like long term growth in the US actually has its own cycle...again, an exponential trend can’t capture this 6 5 Annual Growth Rate 4 3 2 1 0 The HP trend allows trend growth to vary over time 14000 Billions of 2000 Dollars 12000 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 $1,938B (1947Q1) 0 1947 1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 2012 The HP Trend solves this minimization problem $12,129B 2014Q1 How do we best describe long run growth in the US – HP Trend 14000 Billions of 2000 Dollars 12000 $10,967.0B 10000 8000 6000 4000 2000 0 1947 The HP Trend solves this minimization problem 1954 1961 1968 1975 1982 1989 1996 2003 2010 2017 2004Q1 (228 Quarters) Trend $10,967.0 Once we have identified the trend, we can subtract it out to leave the cycle component all by itself. GDP Trend (Average growth) Trend GDP Actual Trend Deviation *100 Trend Actual GDP Time We end up with a series that looks like this % Deviation From Trend Recovery Recession Peak Peak 0 Trough Time Once we have identified the trend, we can remove it. 12000 Billions of 2000 Dollars Actual = $11,849B 11500 Trend = $11,570B 11000 Trend = $10,693B 10500 Actual = $10,417B 10000 9500 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 10,417 10,693 *100 2.6% % Deviation 10,693 2006 2007 % Deviation 2008 11,849 11,570 *100 2.4% 11,570 Here is the cycle by itself Economy Growing Faster than Trend Economy Growing Slower than Trend 3 2 1 0 2000 2002 2004 2006 2008 -1 -2 -3 10,417 10,693 *100 2.6% % Deviation 10,693 % Deviation 11,849 11,570 *100 2.4% 11,570 Let’s look at the cycle component for the US Percentage Deviation from HP Trend 6 4 2 0 1947 1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 2012 -2 -4 -6 -8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 The US has had 11 Cycles since the World War II The US has had 11 Cycles since the World War II Business Cycle Dates Peak Trough Duration (In Months) Contraction Expansion Cycle (Peak from (peak to trough) (Previous trough to this peak) previous peak) Nov 1948 Oct 1949 11 37 45 July 1953 May 1954 10 45 56 Aug 1957 April 1958 8 39 49 April 1960 Feb 1961 10 24 32 Dec 1969 Nov 1970 11 106 116 Nov 1973 March 1975 16 36 47 Jan 1980 July 1980 6 58 74 July 1981 Nov 1982 16 12 18 July 1990 March 1991 8 92 108 March 2001 Nov 2001 8 120 128 December 2007 June 2009 18 73 81 13 55 68 Average When we talk about “business cycle frequency, we are referring to cycles between 2 and 8 yrs. The US has had 33 Cycles since the Civil War. On averages, in recent years, the recessions are getting shorter and the recoveries longer Average (Months) Recession (Peak to Trough) Expansion (Trough to peak) Cycle ( Peak to Peak) 1854 – 2009 (33 cycles) 17.5 38.7 56.2 1854 – 1919 (16 cycles) 21.6 26.6 48.2 1919 – 1945 (6 cycles) 18.2 35.0 53.2 1945 – 2009 (11 cycles) 11.1 58.4 69.5 When we talk about “business cycle frequency, we are referring to cycles between 2 and 8 yrs. It also seems that recently, the business cycle has become less severe in recent years. Percentage Deviation from Trend 6 4 2 0 1947 1952 1957 1962 1967 1972 1977 1982 1987 1992 1997 2002 2007 -2 -4 -6 -8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 2012 In fact, look at the cycle now relative to the great depression era 30 % Deviation from trend Industrial Production 20 10 0 1/1/1919 1/1/1939 -10 -20 -30 -40 Great Depression WWII 1/1/1959 1/1/1979 1/1/1999 13900.0 Actual % Deviation from Trend (Cycle) 13700.0 13,326 12,994 *100 2.5% 12,994 Trend 13500.0 $13,326B GDP 13300.0 $13,118B 13100.0 $12,994B 12900.0 % Deviation from Trend (Cycle) 12, 746 13,118 *100 2.8% 13,118 $12,746B 12700.0 12500.0 2007 Dec 2007 2009 2011 June 2009 Real GDP Trend Real GDP 2013