* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Gongylonema Infection of the Mouth in a Resident of Cambridge

Survey

Document related concepts

Childhood immunizations in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Gastroenteritis wikipedia , lookup

Globalization and disease wikipedia , lookup

Transmission (medicine) wikipedia , lookup

Neglected tropical diseases wikipedia , lookup

Hygiene hypothesis wikipedia , lookup

Urinary tract infection wikipedia , lookup

Sociality and disease transmission wikipedia , lookup

Human cytomegalovirus wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis C wikipedia , lookup

Schistosoma mansoni wikipedia , lookup

Hepatitis B wikipedia , lookup

Onchocerciasis wikipedia , lookup

Neonatal infection wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

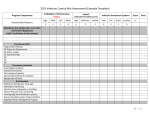

BRIEF REPORT Gongylonema Infection of the Mouth in a Resident of Cambridge, Massachusetts Mary E. Wilson,1,2 Carol A. Lorente,3 Jennifer E. Allen,1,2 and Mark L. Eberhard4 1 Mt. Auburn Hospital, Cambridge, 2Harvard Medical School, Boston, and 3Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard School of Dental Medicine, Boston, Massachusetts; and 4Division of Parasitic Diseases, National Center for Infectious Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Public Health Service, United States Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta We report a case of Gongylonema infection of the mouth, which caused a migrating, serpiginous tract in a resident of Massachusetts. This foodborne infection, which is acquired through accidental ingestion of an infected insect, such as a beetle or a roach, represents the 11th such case reported in the United States. Several nematode parasites can migrate within the superficial soft tissues after being ingested or after entering through the skin. These migrations typically are restricted to the skin, as in the case of cutaneous larva migrans that is caused by various hookworm or Strongyloides species in animals, or they may occur in the skin and other tissues, as in the case of Gnathostoma and zoonotic filarial infections. In humans, only 1 type of nematode localizes primarily in the oral cavity: Gongylonema species. Some 40–50 cases of gongylonemiasis in humans have been reported, including cases from Europe, North Africa, China, New Zealand, Sri Lanka, and the United States [1, 2]. We report the 11th case of gongylonemiasis that has occurred in the United States, to alert physicians to the characteristic clinical and parasitologic findings associated with such infection. Case report. In September of 1999, a healthy, 38-year-old schoolteacher sought medical evaluation for what she described as the presence of a worm in her mouth. Approximately 6 months earlier, she had noted in her cheek an irregular area that she could feel with her tongue. She thought that it was a Received 19 June 2000; revised 21 September 2000; electronically published 9 April 2001. Reprints or correspondence: Dr. Mark L. Eberhard, Division of Parasitic Diseases F13, CDC, 4770 Buford Hwy. NE, Atlanta, GA 30341-3724 ([email protected]). Clinical Infectious Diseases 2001; 32:1378–80 2001 by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. All rights reserved. 1058-4838/2001/3209-0020$03.00 1378 • CID 2001:32 (1 May) • BRIEF REPORTS patch of dry mucosa. Two days before she was seen, the patient had noted that the patch was a mass that was migrating. She had been able to see a serpiginous, transparent form that she described as looking like a cellophane noodle. She estimated that the rate of movement of this form was 2–3 cm per day. She had no associated symptoms, and she denied having fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, sore throat, or other skin lesions. In April 1999, the patient had vacationed for a week in Mexico near the Guatemalan border. During a day trip to the mountains, she had gone swimming in a pond located adjacent to waterfalls and had also eaten a local dish, which she thought might have contained cabbage. She said that the food was raw, crunchy, and saladlike. Approximately 12 h after eating this food, she and 5 other individuals became ill with nausea, vomiting, and dizziness. The acute illness resolved without specific treatment. The patient reported that she had frequently eaten sushi in the United States, but she indicated that she had never (intentionally) ingested beetles. The patient had moved from France to the United States in 1981, but she returned to France at least once each year for visits. She had spent 3 weeks in France in July 1999, after the onset of symptoms. She had also visited Italy in 1995, but she had never visited Asia or Africa. Her only trip to Latin America was the aforementioned trip to Mexico. The patient’s past medical history included appendectomy and tonsillectomy. Her complete blood count was normal and showed no increase in eosinophils. Examination of the patient’s mouth revealed a superficial, filamentous, submucosal mass (diameter, 0.2 mm) in a sinusoidal shape. The total size of the mass was ∼1.0 cm2. During a period of 4 days, it migrated from the right side of the buccal mucosa to the midline of the lower lip, and at one point it migrated to a deeper position under the vermilion border of the lip and was barely visible. It subsequently (within 24 h) migrated to a more superficial position. With use of topical anesthesia (20% benzocaine gel), the mandibular buccal mucosa was anesthetized, and a small spoon curette was placed under the middle of the filament. The filament was gently teased from the mucosa, removed intact, and placed in a 95% alcohol solution. There was no local bleeding or discomfort. Albendazole, 200 mg given twice daily, was prescribed for 3 days. After having taken 3 doses, the patient discontinued taking albendazole because of nausea. She noted no changes in her mouth after the removal of the parasite. Specimen. A small, female nematode was received for study; the specimen was intact and was ∼25 mm in length by the feces of the aforementioned species and require ingestion by an appropriate insect host, such as a cockroach or a dung beetle. The parasite undergoes obligate development to the infective stage within the insect (20–30 days after ingestion), and infection of the definitive vertebrate host occurs after ingestion of the insect. Adult worms require some 60–80 days to develop in the definitive host after ingestion of an infected insect. In humans, ingestion is typically accidental and unrecognized. None of the data from recorded cases of G. pulchrum infection have indicated that the infected patients had knowingly ingested insects. Although the life cycle of G. pulchrum is well known, the factors that put some people at increased risk for infection with G. pulchrum are not clearly understood. It is plausible that the risk of eating insect-contaminated food is increased in areas where levels of sanitation are poor, including some areas visited by travelers. In some parts of the world and in some cultures, insects are an important source of protein and calories, and gongylonemiasis could potentially be a risk for those who eat uncooked insects. Presumably, a roasted or otherwise well-cooked insect would pose no risk of Gongylonema infection. Entomophagy (eating insects) has been practiced throughout Figure 1. Photomicrograph of anterior end of worm illustrating the bosses (arrows) characteristic of organisms of the genus Gongylonema. Scale bar, 50 mm. 0.2 mm in maximum diameter at midbody. The anterior end of the worm was slender and threadlike, and it had a maximum diameter of only 0.05 mm, whereas the posterior end of the worm was stout and did not taper appreciably. The most anterior 0.8 mm of the worm (figure 1) bore bosses (scutes) that were typical of organisms of the genus Gongylonema. Beginning just posterior to the bosses on the anterior end, the cuticle bore prominent transverse striations (figure 2). These striations continued to the tail, but they diminished in prominence near the posterior end of the worm. The esophagus was long (length, 5 mm). The ovejector was prominent and was located 1.7 mm anterior to the tail. The tail was conically tapered and was 0.2 mm in length. The worm was gravid, and fully embryonated eggs were present in the uteri (figure 2). Discussion. Gongylonema pulchrum is the species that has been identified as the cause of Gongylonema infection in humans [1, 2]. Infection caused by this species has been reported to occur in sheep, cattle, pigs, and other ungulates, and in bears and monkeys. The life cycle of G. pulchrum requires an insect as the intermediate host. Fully embryonated eggs are passed in Figure 2. Photomicrograph of a worm at midbody illustrating the embryonated eggs in utero. The transverse striations of the cuticle are visible but out of focus. Scale bar, 25 mm. BRIEF REPORTS • CID 2001:32 (1 May) • 1379 history, and it remains common today in some parts of the world [3, 4]. Even though they may not know it, humans regularly eat insects and insect parts, and the US Food and Drug Administration has developed guidelines for the allowable number of insect eggs, immature and adult insects, and insect parts that can be present in various foods (e.g., up to 30 insect fragments per 100 g of peanut butter; 475 insect fragments per 50 g of ground pepper; and 35 fruit fly eggs and 10 whole or equivalent insects in every cup of golden raisins) [5]. Because of the cosmopolitan distribution of Gongylonema species, travel to an exotic location is not necessary for infection to occur. The woman who we describe may have ingested the parasite along with insect parts consumed in Mexico 5 months before the parasite was identified, but she just as well could have acquired the infection in the Cambridge, Massachusetts area. Although there is scant published literature on this topic, reported experience would suggest that infection may persist for many months but that it ultimately is self-limiting. The parasite can be removed without the use of complicated invasive procedures, and serious complications of infection have not been reported. Of the 11 reported cases from the United States, the majority have been reported among persons living in the southeastern states, although the last 2 cases have been from large cities in the Northeast. The infections have been reported in adults, men and women have seemed to be equally affected, and the clinical presentation has been relatively uniform. Patients frequently have described the sensation of an object moving in the mouth, and as often as not, they have removed the worms themselves. For urban residents, infection with G. pulchrum should be an unusual occurrence, given the nature of the usual hosts. On the other hand, infection with Gongylonema neoplasticum, which is a natural and common parasite among rats, would seem to be a much more likely cause of human infection because of the ubiquitous distribution of rats. The specimen from the present case, and the specimen from the most recent previous report of Gongylonema infection in a resident of New York City [6] were compared with G. neoplasticum material (which included 2 lots of worms collected from rats in New Orleans [kindly provided by Dr. M. D. Little]). Clearly distinct morphological differences, especially with regard to the shape of the female tail, were evident in a comparison of the specimens obtained from humans and the G. neoplasticum material. 1380 • CID 2001:32 (1 May) • BRIEF REPORTS Although worms collected from humans usually have been smaller than the average size range reported for G. pulchrum, a wide range in size has been noted for that species, depending on the host from which the worms were recovered [7]. Because of an absence of male worms in most cases, it has not been possible to definitively identify the species, but it most likely is G. pulchrum. Treatment with albendazole, a broad-spectrum anthelmintic, was initiated because of the concern that additional worms might still be present. There is no confirmed proof that treatment with albendazole or any other anthelmintic results in a cure in humans. However, because of the wide margin of safety associated with this drug and the possibility of additional worms being present, treatment seems to provide some advantages over no treatment. Treatment done by removal of worms either by use of the fingers or by use of a curette in a physician’s office can also be successful. Clinicians, other health care providers, and microbiologists alike need to be alert to the possibility of infection with Gongylonema species. The characteristic clinical finding of a wormlike object migrating in the mouth area, including the buccal mucosa, gums, lips, or palate, should be a clear signal for consideration of Gongylonema infection in the differential diagnosis. References 1. Cappucci DT, Augsburg JK, Klinck PC. Gongylonemiasis. In: Steele JH, ed. Handbook series in zoonoses, section C: parasitic zoonoses. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1982:181–92. 2. Gutierrez Y. Other tissue nematode infections. In: Guerrant RL, Walker DH, Weller PF, eds. Tropical infectious diseases: principles, pathogens and practice. New York: Churchill Livingstone, 1999:933–48. 3. Gordon DG. The eat-a-bug cookbook. Berkeley, California: Ten Speed Press; 1998. 4. Yoshimoto CM. Entomophagy and survival. Wilderness Environ Med 1999; 10:208. 5. Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, US Food and Drug Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. The food defect action level. May 1995. Revised in March 1997 and in May 1998. Also available through the US Food and Drug Administration Web site (http://www.cfsan.fda.gov/∼dms/dalbook.html). 6. Eberhard ML, Busillo C. Human Gongylonema infection in a resident of New York City. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1999; 61:51–2. 7. Lichtenfels JR. Morphological variation in the gullet nematode, Gongylonema pulchrum Molin, 1857, from eight species of definitive hosts with a consideration of Gongylonema from Macaca spp. J Parasitol 1971; 57:348–55.