* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download value for money model

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

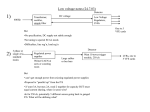

Nexus Quality Contracts Scheme Proposal Value for money modelling This note explains how Nexus has modelled the value for money (vfm) measurements contained within the Quality Contracts Scheme (QCS), giving confidence that the Proposal is economic, efficient and effective. Approach The vfm model takes key information from the affordability model (see separate guide on ‘Affordability Modelling’). It follows the latest Department for Transport (DfT) guidance for appraising transport schemes (known as WebTAG, last updated August 2012). It is largely spread sheet based modelling tool, although it uses an add‐on tool called ‘@Risk’ to run the same basic information several times using different inputs and assumptions. This allows a comparison to be made between three different scenarios, namely: Do Something, the QCS; Do Minimum, the status quo; and Do VPA, the NEBOA partnership offer. Nexus considers that a QCS will represent value for money if, in comparison with the Do Minimum and Do VPA alternatives, it delivers monetised benefits (ie. those benefits that can be quantified in financial terms) which exceed the monetised costs and disbenefits, at an acceptable and sustainable level of cost and delivery risk. In order to quantify the benefits, costs and disbenefits the appraisal considers: The benefits to be enjoyed by existing users of buses due to changes in bus service provision and the fares they pay; The benefits to be enjoyed by additional new bus users who start to use the bus because of the enhanced quality of service; Benefits to non‐users due to fewer vehicles on the road (as some of the new users would otherwise be car users), leading to less congestion, fewer road traffic accidents, lower emissions, less traffic noise, changes in revenue from fuel duty and lower maintenance costs; The costs incurred and revenues accruing to the public sector; and The costs incurred and revenues accruing to the Operators. Benefits WebTAG sets out that benefits should be monetised using time savings. This is relatively straightforward where journey times are made faster by the scheme, or where passengers’ waiting time is reduced. However where the scheme’s benefit relates more to journey quality than to journey time (for example the Customer Charter proposed in the QCS), time saving ’equivalents’ are set out in WebTAG. All time savings and time saving ‘equivalents’ are multiplied by the number of people receiving the benefit. Finally, WebTAG sets out a range of financial values for the time savings that are used to calculate monetised benefits. The overall impact of the QCS Proposal on highway travellers is calculated as a result of changes in the number of vehicles on the road i.e. additional bus and reduced car journeys (in comparison to the status quo). These changes then have a financial value applied using ‘impact per km’ monetary values specified in WebTAG. The Proposal sees revenues that would have previously been earned by bus operators (fare income, concessionary travel and BSOG) transferred to the public sector. Costs The costs taken into account include scheme set up and on‐going costs, contract payments under the scheme, changes in Concessionary Travel funding and secured service funding. The impact also includes the reduction in indirect taxes received by HM Treasury from increased consumer spend on (untaxed) public transport fares and reduced spend on fuel from the net reduction in vehicle km travelled. The small saving in Tyne & Wear Districts' highway maintenance spending as a result of reduced highway km travelled is also taken into account. Value for Money Economy, efficiency and effectiveness, when considered collectively, are closely associated with the concept of public sector value for money. In this context, value for money is a measure of the justification for investment, where the benefits from a scheme must exceed the costs of delivering it. Public sector value for money as defined in HM Treasury’s Green Book ‘Appraisal and Evaluation in Central Government’ also applies to all local government investment. It can be applied to the Proposal. Efficiency is considered by looking at the ratio of benefits and revenues compared to the costs associated with the delivery of these benefits and revenues. It allows a comparison between different uses of the same resources over the ten‐year life of the Proposal. A figure greater than 1 is considered to be efficient. Economy is considered by looking at the net present value, which is the difference between the benefits of the QCS and the cost of delivering them (by both the public sector and the bus operators). Nexus considers that the net present value is a better and more appropriate measure of the economic criteria than cost alone, as it takes into account the adverse financial impact on the Operators and measures the scale of the overall impact. Effectiveness is considered by looking at the benefits and revenues generated by the alternative proposals and the level of confidence that the stated improvements will be delivered. Risks WebTAG sets out how the risks associated with the realisation of costs and benefits should form part of the value for money assessment. Risks modelled represent four broad areas of uncertainty: Where there is uncertainty in the input value for any reason, for example: a) in the base number of passengers, due to the method of estimation; or b) in total bus operating hours, where limited information has been provided by the Operators. Where the model at an aggregate level across Tyne and Wear level may not robustly represent the market response. For example, where use of an average fare may not represent the fare structure applicable to individual passengers. Inputs defining future year forecasts, for example the change in market size in response to demographic changes or fares changing at a different rate to general inflation. Inputs reflecting the impact of the assessed intervention. The vfm model includes a risk simulation exercise, where multiple iterations of the model have been run with different combinations of input assumptions. The output of the risk simulation is expressed as a probability range rather than as a single 'central case' value. This approach allows us to assess how much confidence we can have that the eventual outcome of the QCS Proposal will reflect the appraisal. Taking all three measures together, in over 90% of modelled simulations a positive benefit is obtained.