* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download 19-Consumer Choice

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

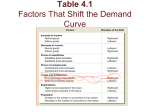

CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY If our hearts you’d weigh, Beware of our pretending. Forget the things we say, And scrutinize our spending. Fundamentals of Consumer Choice The study of consumer choice requires that we make certain assumptions: 1. Limited income necessitates choice. We must economize because we always want more than our resources will allow us to obtain. (Economizing behavior) 2. Consumers make choices purposefully. They do not knowingly choose a product or service if that choice necessitates giving up a higher valued alternative. In a sense, consumers are rational. 3. Goods can be substituted for one another, within limits and to varying degrees. 4. Decisions normally are made without perfect information, but knowledge and past experience will help. (Information costs reduce available information.) 5. The law of diminishing marginal utility is always at work: As the rate of consumption increases, the utility (or benefit, or satisfaction, or pleasure) derived from consuming additional units of a good eventually will decline. Diminishing Marginal Utility + 0 Quantity – Marginal Utility CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY When we speak of marginal utility, we mean: Marginal Utility = Change in Total Utility Change in Quantity where Total Utility is a measure of the total satisfaction derived from consuming a quantity of some good or service. Total utility tends to look like this when graphed: Total Utility + 0 Quantity – We can discuss several examples of the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility: 1. Let’s say you go to an all-you-can-eat buffet. You can eat all you want (but no doggy bags are allowed), but after a few plate loads, you have had enough. You say you are “full.” An economist says that you have reached the point of negative marginal utility. 2. Attendance at a baseball game. Even though fans love the game, some of them will leave before the end of the ninth inning. If the game goes into extra innings, even many die hard fans will have had enough and begin to find their way out of the stadium. 3. Even if you really like a certain product a lot, the law of diminishing marginal utility explains why you won’t spend your entire budget on that product. 4. Economics lectures. ‘Nuff said. Let’s use the law of diminishing marginal utility to explain individual demand. The law of diminishing marginal utility states that as consumption per unit of time increases, utility derived from succeeding units declines. Marginal utility declines. The height of an individual’s demand curve indicates the maximum price the consumer would be willing to pay for that unit. A consumer’s willingness to pay for a unit of a good is directly related to the utility derived from consumption of the unit. The law of diminishing marginal utility implies that a consumer’s marginal benefit, and thus the height of their demand curve, falls with the rate of consumption. Consumer Choice Page 2 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY An individual’s demand curve, Jones’s demand for frozen pizzas in this case, reflects the law of diminishing marginal utility. Because marginal utility (MU) falls with increased consumption, so does a consumer’s maximum willingness to pay—marginal benefit (MB). A consumer will purchase until MB = Price . . . so at $2.50 Jones would purchase 3 frozen pizzas and receive a consumer surplus shown by the shaded area (above the price line and below the demand curve). In the real world, we don’t limit ourselves to just pizza. We buy many different goods. But how do we decide when we have enough of one good and not enough of another good? Each consumer will maximize his/her satisfaction by ensuring that the last dollar spent on each commodity yields an equal degree of marginal utility. This is the utility maximizing rule. This is also known as the equimarginal principle or the balancing of marginal utilities. Consumer Choice Page 3 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY The discussion about marginal utility and price is a key to proper understanding of the demand curve. A numerical example should help to illustrate why total utility is maximized when: MU a Pa = MU b Pb = … = MU n Pn Example Product A: Price = $1 Product B: Price = $3 Income = $10 Units of Product MUA* MUA/PA MUB* MUB/PB 1 10 10 24 8 2 9 9 21 7 3 8 8 18 6 4 7 7 15 5 5 6 6 9 3 6 4 4 6 2 7 2 2 3 1 * Independent of each other. Take all possible combinations of A and B to spend all income and compare total utility. Consumer Choice Option Product A Product B Total Utility 1 1 3 73 2 4 2 79 3 7 1 70 Page 4 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Option 2 provides the highest level of utility, and it represents the combination of goods A and B where MU/P is equal [at 7]. There is another way to explain this concept to help reinforce it: Why will consumers decide to purchase combinations of goods so as to equate MU/P for each good? Initial Situation MUx = 10, Px = $1, MUx/Px = 10 MUy = 20, Py = $2, MUy/Py = 10 New Situation Price of X falls to $0.50 MUx = 10, Px = $0.50, MUx/Px = 20 At the new lower price, consumers will want to purchase more of X [and less of Y]. The law of diminishing marginal utility suggests that as X is used more intensively, MUx will fall. Likewise, as Y is used less intensively, MUy will increase. Phase 1 MUx = 9, Px = $0.50, MUx/Px = 18 MUy = 22, Py = $2, MUy/Py = 11 Phase 2 MUx = 8, Px = $0.50, MUx/Px = 16 MUy = 24, Py = $2, MUy/Py = 12 Phase 3 MUx = 7, Px = $0.50, MUx/Px = 14 MUy = 28, Py = $2, MUy/Py = 14 At this point, MU/P is the same for both goods, so there is no further adjustment. Consumer Choice Page 5 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Optional Material on Indifference Curves We can graphically portray the budget constraint (also called the consumption opportunity constraint): Good Y Budget Constraint Good X Let’s leave this for a moment to consider indifference curves. An indifference curve is a curve representing all combinations of goods that are equally preferred by a consumer; that is all combinations whereby the consumer is indifferent as to the choice of consumption bundles. Good Y I Good X For example, we might like 4 apples and 2 oranges or we might like 2 apples and 3 oranges. We might be indifferent as to which bundle of goods we choose. Characteristics of indifference curves: 1. More goods are preferable to fewer goods (outer curves are preferred). 2. Goods are substitutable (downward slope). Consumers are willing to give up some of one good to get more of another good. Consumer Choice Page 6 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY 3. Indifference curves are convex to the origin. This reflects the declining marginal rate of technical substitution as a good is consumed more intensively. To simplify: As people consume more of one good, it takes the receipt of increasing portions of the other good to continue the rate of consumption of the first good (while staying on the original indifference curve). Good Y I Good X 4. Indifference curves are “everywhere dense.” They can be drawn anywhere. There are no combinations of goods that cannot be compared by the consumer. Good Y I II III Good X 5. Indifference curves cannot cross. Otherwise characteristic one would be violated. Good Y B A C I II Good X Consumer Choice Page 7 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY If II is preferable to I, it would imply that point B is preferable to point A. But since point B is liked as much as point C (they lie on the same indifference curve) and since point A is also liked as much as point C (they also lie on the same indifference curve), points A and B should also be liked as much as each other. [Remember that each point represents combinations of goods Y and X that might be one bundle available to the consumer.] What do we do with indifference curves? Three things: 1. Utility maximizing combinations of goods; 2. Price changes and consumer choice; and 3. Income and substitution effects. Utility maximizing combinations of goods If we assume an Indifference Map of the following type: Good Y III I II Good X Now add the budget constraint. Good Y I II III Good X What combination of goods will the consumer choose? Consumer Choice Page 8 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY What would happen if the consumer had more income? Good Y I III II Good X Price changes and consumer choice The demand curve shows the amount of a product consumers would be willing to buy at different prices during a specific period. The law of demand states that the quantity of a product purchased is inversely related to its price. Reasons the demand curve slopes downward: • Substitution effect: as a product’s price falls, consumers will buy more of it…and less of other now more expensive products. • Income effect: as a product’s price falls, a consumer’s real income rises and so induces the individual to buy more of both it and other goods. Good Y II I Good X Price of X is reduced. More of X can be purchased for the same amount of money. No change in how much of Y that can be purchased (if none of X is purchased). Move to a higher indifference curve and change the combination of goods purchased. Consumer Choice Page 9 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Income and substitution effects Income effects are the adjustments people make because the purchasing power of a given income is altered when prices change. The substitution effect is that portion of the change in quantity demanded due solely to a change in relative prices. As prices rise and fall, consumption will be altered by income and substitution effects. Good Y B C II A I 0 10 12 Good X 15 AB = Income Effect (indicates that an individual’s income can buy more of all goods when the price of one good declines, ceteris paribus). BC = Substitution Effect (indicates that following a decrease in the price of a good or service, an individual will purchase more of the now less-expensive good and less of other goods). MRTS at A is same as at B (=slopes equal). This shows no change in substitution. It is a total income effect. The line tangent to point C has a different slope (and MRS). When the MRS changes, there has been a substitution effect. The total change in quantity is 5 units (from 10 to 15). The income effect is 2 units (from 10 to 12), while the substitution effect is 3 units (from 12 to 15). The income effect reinforces the substitution effect in the case of a normal good. Normal goods are any goods for which demand increases when income increases, i.e., with a positive income elasticity of demand. The term does not refer to the quality of the good. Inferior Goods The income effect offsets the substitution effect in the case of an inferior good. An inferior good is a good that has the property that when a person’s income rises, the demand for the inferior good falls. Inferiority, in this sense, is an observable fact rather than a statement about the quality of the good. Consumer Choice Page 10 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Inter-city bus service is an example of an inferior good. This form of transportation is cheaper than air or rail travel, but is more time-consuming. When money is constricted, traveling by bus becomes more palatable, but when money is more abundant than time, more rapid transport is preferred. Inexpensive foods like potatoes, hamburger, mass-market beer (as opposed to craft beer), frozen dinners, and canned goods are additional examples of inferior goods. As a person's income rises one tends to purchase more expensive foods. Likewise, objects heavily used by poor people and related services for which richer people have alternatives exemplify inferior goods. As a rule, used and obsolete goods (but not antiques) marketed to persons of low income as closeouts are inferior goods at the time even if they had earlier been normal goods or even luxury goods. News Item from November 2008—The economy is in tatters and, for millions of people, the future is uncertain. But for some employees at the Hormel Foods Corporation plant here, times have never been better. They are working at a furious pace and piling up all the overtime they want. The workers make Spam, perhaps the emblematic hard-times food in the American pantry... Even as consumers are cutting back on all sorts of goods, Spam is among a select group of thrifty grocery items that are selling steadily. Pancake mixes and instant potatoes are booming. So are vitamins, fruit and vegetable preservatives, and beer, according to data from October compiled by Information Resources, a market research firm. “We’ve seen a double-digit increase in the sale of rice and beans,” said Teena Massingill, spokeswoman for the Safeway grocery chain, in an e-mail message. “They’re real belly fillers.” Economics students will recognize these as inferior goods: Goods for which demand rises when income falls. Note: “Inferior” is not a pejorative, just a description of the sign of the income elasticity. A Giffen good is one that people consume more of as price rises, violating the law of demand. In normal situations, as the price of such a good rises, the substitution effect causes people to purchase less of it and more of substitute goods. In the Giffen good situation, cheaper close substitutes are not available. Because of the lack of substitutes, the income effect dominates, leading people to buy more of the good, even as its price rises. Consumer Choice Page 11 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Evidence for the existence of Giffen goods is limited, but microeconomic mathematical models explain how such a thing could exist. Giffen goods are named after Sir Robert Giffen, who was attributed as the author of this idea by Alfred Marshall in his book Principles of Economics. Demand Reflects Consumer Preferences Good Y Price-Consumption Curve C B III II A I P3 P2 P1 Good X Price P3 P2 P1 Demand Quantity of Good X Consumer Choice Page 12 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY How will consumers respond to an increase in income taxes? They would buy less of both goods. Good Y B 60 II 40 A I 0 Good X 10 12 How will consumers respond to a change in a sales tax? They might buy less of both the taxed good and all other goods. Good Y B 50 II 45 A I 0 10 Good X 15 Time Cost and Consumer Choice The monetary price of a good is not always a complete measure of its cost to the consumer. Consumption of most goods requires time as well as money. Like money, time is scarce to the consumer. • So, a lower time cost, like a lower money price, will make a product more attractive. • Time costs, unlike money prices, differ among individuals. Consumer Choice Page 13 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Consider the example of waiting in line for gas when the price is not allowed to ration the product to people who would like more of it. Elasticity of Demand Price elasticity reveals the responsiveness of the amount purchased to a change in price. A numerical example: Suppose Trina bakes specialty cakes. She can sell 50 specialty cakes per week at $7 a cake, or 70 specialty cakes per week at $6 a cake. What is the demand elasticity for Trina’s cakes? After calculating the price elasticity of demand, you can determine whether it is elastic, inelastic, or unitary elastic with the following chart: Consumer Choice Page 14 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Because price elasticity of demand is always negative, the sign on the coefficient is often omitted in discussions of elasticity. We often use graphs to show relative elasticity of demand. Consumer Choice Page 15 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY However, a more technically correct approach is to use the elasticity coefficient. Part of the reason is that the elasticity of demand actually changes for a straight line depending on where on the line the measure is made. Consumer Choice Page 16 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Determinants of Price Elasticity of Demand • Availability of substitutes o When good substitutes for a product are available, a rise in price induces many consumers to switch to another product. o The greater the availability of substitutes, the more elastic demand will be. • Share of total budget expended on product o As the share of the total budget spent on the product increases, demand is more elastic. If the price of a product increases, consumers will reduce their consumption by a larger amount in the long run than in the short run. Thus, demand for most products will be more elastic in the long run than in the short run. This relationship is often referred to as the second law of demand. Consumer Choice Page 17 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Total Expenditures and Demand Elasticity Income Elasticity Income elasticity indicates the responsiveness of a product’s demand to a change in income. Consumer Choice Page 18 2/24/10 CHAPTER 19—CONSUMER CHOICE & ELASTICITY Price Elasticity of Supply The price elasticity of supply is the percent change in quantity supplied divided by the percent change of the price causing the supply response. • Analogous to the price elasticity of demand. • However, the price elasticity of supply will be positive because the quantity producers are willing to supply is directly related to price. Consumer Choice Page 19 2/24/10