* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download JUNO BEACH: SIXTY YEARS LATER Introduction

Consequences of Nazism wikipedia , lookup

Diplomatic history of World War II wikipedia , lookup

British propaganda during World War II wikipedia , lookup

Causes of World War II wikipedia , lookup

Omaha Beach wikipedia , lookup

Technology during World War II wikipedia , lookup

Operation Bodyguard wikipedia , lookup

Écouché in the Second World War wikipedia , lookup

Military history of Canada during World War II wikipedia , lookup

End of World War II in Europe wikipedia , lookup

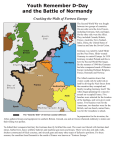

JUNO BEACH: SIXTY YEARS LATER YV Introduction Focus This News in Review story focuses on Canada’s contribution to the largest military invasion in history—the Allied assault on Normandy. The diamond anniversary of this critical battle was recently celebrated, in June 2004. Definition D-Day and H-Hour are military terms that stand for the day and hour when a military campaign will begin. Troops aren’t told the exact time of the attack until the last minute, and sometimes D-Day and H-Hour change drastically, as occurred in 1944. YV Sections marked with this symbol indicate content suitable for younger viewers. To supplement their air-reconnaissance photographs of the coast of France, Allied planners asked citizens to mail in any postcards they had purchased while vacationing in France. They hoped that the photographs of the coastal landscape on these postcards would give them a better idea of the terrain. On the first day 30 000 postcards arrived. In the next few weeks, 10 million more came flooding through the post. Everyone wanted to do something—anything—to help their sons, fathers, husbands, friends, and sweethearts succeed in what they were soon to face. The big day that everyone dreaded— D-Day—was coming soon. The Allied forces had been preparing for this day for more than four years. On D-Day, Canadian, British, and U.S. forces would invade mainland Europe, a continent occupied by the Axis powers of Germany and Italy. First, they would get a foothold on the beaches of Normandy, France. Then they would fight their way across the continent to the heart of Nazi Germany. • Concrete pillboxes, fortified houses, deep trenches, and machine-gun emplacements would shoot down soldiers who made it to the beach. • Landmines, concrete barriers, and barbed wire placed all along the beach would keep Allied troops on the beach, where they could be shot. How to breach the walls of Fortress Europe? By blasting through it with so much firepower and so many attackers that some soldiers would make it through. D-Day would be the largest military invasion force in history. The Allies gathered together 156 000 fighting men to invade 80-kilometres of coast. Of these, 14 500 were Canadian troops, in 14 battalions and regiments. A further 27 000 Canadians took part as members of the Royal Canadian Navy, Air Force, and Army, in support roles. Thousands more participated as members of Britain’s Royal Navy and Air Force. All these Canadians had been training in England for this day since they had first signed up at the beginning of the war. Fortress Europe That first step—getting a foothold on the beaches of Normandy—would be difficult. Hitler had turned Europe into a fortress. There were 210 000 German troops spread along the coast, and the German army had barricaded the whole Atlantic shoreline to prevent just such an attack from England. • Barricades and mines in the water would prevent easy landings. • Placements of 88-millimetre cannons and naval guns would fire on ships 20 kilometres out to sea. At Daybreak On the morning of June 6, German soldiers peered out from their coastal bunkers to see a vast flotilla of 7 000 ships and 4 000 landing craft emerge from the morning mist. There were so many ships, the soldiers would say, that you could have lined them up end to end and skipped back to England. But these ships carried men set on a deadly mission: to attack Fortress Europe, to create a foothold in Normandy, and to fight for freedom. These young soldiers were frightened, they were seasick, and many just wanted to go home. But they CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 44 The Combatants Allied countries: Australia, Canada, China, Great Britain, New Zealand, South Africa, Soviet Union, and United States Countries occupied by the Axis powers that had resistance movements: Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Greece, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, and Yugoslavia Axis countries: Bulgaria, Finland, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Japan, Manchuria, and Romania stayed and did what had to be done. The 3rd Canadian Infantry Division and the 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade together were assigned a stretch of beach code-named Juno. British divisions were assigned Sword and Gold Beaches, and U.S. divisions were assigned Utah and Omaha Beaches. It was a long and bloody day. But 10 hours after H-Hour, Canadian troops had pushed 13 kilometres inland to the outer defences of the town of Caen. This action secured success in the British-Canadian sector. A beachhead had been secured, the Western Front had been opened, and the battle for Europe could begin. To Consider 1. Put yourself in a soldier’s position. How would you feel as you travelled across the channel and were informed that this was not an exercise but the real thing? 2. What defences did the Canadians have to face when they reached the coast of France? Did you know . . . The 2004 diamond anniversary (60 years) celebrations of D-Day represent probably the last major celebration of the June 6, 1944, landings? Most of the participants are either dead or in their late 70s and 80s. From now on, it will be up to younger Canadians to keep alive the memories of that momentous day. 3. How might the success of Canada’s soldiers on D-day affect Canadians’ sense of national identity? 4. What can young Canadians today do to ensure that the memory of this important event is never lost? CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 45 JUNO BEACH: SIXTY YEARS LATER YV Video Review Complete the questions in Part I of this exercise while reviewing the video. Later you can attempt the second part of the exercise. Part I During the Second World War, Adolph Hitler and Germany attacked and occupied much of continental Europe, including France. The allies attacked France on D-Day with the long-term goal of recapturing all of Europe from the German armies. 1. What did the Allies do on June 6, 1944? 2. This day is commonly known as _________________________________ 3. Juno Beach is located in ________________________________________ 4. Identify at least three ways the Germans tried to make it difficult to land on the beaches of France. 5. What was the name of the famous German general who was leading the German defence? ___________________________________________ 6. Which countries fought beside Canada that day? 7. How many Canadians were killed or wounded on that first day? _________ 8. How far inland did the Canadians reach on the first day? ________________ 9. How many Canadians were killed or wounded before they could fight their way beyond Normandy? _________________ 10. Why do the French still come out to applaud the actions of men from so many years ago? 11. According to Governor General Adrienne Clarkson, why did the Canadians invade Europe? 12. How old was Gérard Doré of Roberval, Quebec, when he died in Normandy?___________ CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 46 13. Why did the Queen say thank you? 14. One invitation to the celebrations was a controversial one. Who was the person invited and why was this so controversial? 15. How many Germans died in the Normandy campaign? ______________ 16. What is the purpose of the Juno Beach Centre? Part II – Crossword Complete this crossword on Juno Beach using the words at the bottom to help you answer the questions. Across 2. One of the two beaches where the British attacked 3. One of the two beaches where the U.S. attacked 4. Month when D-Day occurred 5. Country that was occupying France at the time 7. Name of the war in which D-Day occurred Down 1. Country where the Allies launched D-Day 2. Years that have passed since D-Day (at the time of filing) 3. Code name for the D-Day operation 4. The beach where the Canadians attacked 5. One of the two beaches where the British attacked 6. One of the two beaches where the U.S. attacked 1 3 2 4 5 6 7 CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 47 Words to choose from: France Germany Gold June Juno Omaha Overlord Sixty Sword Utah World War Two JUNO BEACH: SIXTY YEARS LATER YV Canadians in the Second World War Note: This very brief account focuses on the European front in the Second World War. The war in the Pacific is yet another story. Background to War The Second World War began when two nations began stretching their military muscle and started invading independent neighbouring countries. In Italy, Benito Mussolini ruled his country with an iron fist. His Fascist regime embraced a totalitarian doctrine that combined nationalistic and elitist ideas. He invaded Ethiopia in 1935, ignoring world opinion. His success encouraged the future aggression of Adolf Hitler of Germany. Germany was humiliated after the First World War, when it was stripped of its colonies and had to compensate the victors of the war, as laid out by the Treaty of Versailles (1919). Economic depression further destabilized Germany, making it possible for the charismatic leader Adolph Hitler to come to power in 1933. His party, the National Socialist Party of German Workers (National-Sozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei, or NSDAP), otherwise known as the Nazi Party, promised that Germany would rise to greatness once more, both economically and militarily. Through violence and intimidation Hitler eliminated his political opposition. In 1935, Hitler enacted the Nuremberg Racial Laws, which denied Jewish German citizens their rights. On the night of November 9, 1938, members of Nazi youth organizations attacked Jewish neighbourhoods. They burned down synagogues, vandalized 7 500 stores, and arrested 26 000 Jews, whom they began to send to concentration camps. Germany annexed Austria in 1938, and then seized Czechoslovakia in 1939. Although Canadians hoped that war could be avoided, it appeared that the violent regime in Germany could not be contained. Canada Goes to War In August 1939, Germany invaded Poland. Great Britain sided with Poland and signed a mutual protection treaty. After Germany attacked on August 30, Britain and France declared war on Germany, on September 3. Should Canada go to war? Canadians well remember how many of their young men had died in Europe during the First World War, but they could not deny that Hitler had to be stopped. On September 10, Canada joined the war effort. Canada’s military was not in great shape, so the first task of Mackenzie King’s government was to prepare. Volunteers were welcomed into the army, navy, and air force. Industry and agriculture were diverted for war purposes, such as building ships and manufacturing munitions. Canada became a training centre for pilots from all over the Commonwealth. In the meantime, Germany invaded and conquered many of the countries of Western Europe. Britain braced itself for attack. Some Key Events Battle of Britain—On July 10, 1940, Hitler attacked Britain. British and Canadian forces responded by bombing Berlin and then beat off German raids in the skies over London. After heavy losses, Hitler postponed his invasion of Britain. Germany invades the Soviet Union— In June 1941, Hitler made probably his biggest mistake of the war when he CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 48 Definition Conscript refers to a soldier forced to enlist and fight rather than a volunteer who freely chooses to enlist and do battle. Conscription in both world wars seriously divided Canadians. Did you know. . . Over the six years of the Second World War, more than one million Canadians (including 50 000 women), or one-tenth of the population, went into uniform to fight for freedom? Unlike the armies of our Allies, virtually all of our soldiers were volunteers, fighting to free the world of tyranny. Of these men and women, 45 000 lost their lives, and many more suffered permanent injuries. invaded the giant to the East. He underestimated the Soviet Union’s determination to fend him off, and the Eastern Front continued to rage until the end of the war. This battlefront bled Germany white. Attack on Pearl Harbour—On December 7, 1941, Japan, an ally of Germany, attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, thereby crippling the U.S. Navy in the Pacific and bringing the United States into the war against Japan, Germany, and Italy. Attack at Hong Kong—Canadian defenders were unable to thwart Japanese aggression on this British colony in December 1941. At the end of the battle, 286 Canadians were dead. A further 266 died in concentration camps. Battle of Dieppe—On August 19, 1942, a Canadian force of 5 000 soldiers, with about 1 000 British soldiers, attacked the well-defended port of Dieppe on the coast of France. The raid was intended to test the German defences and distract the German army from the Eastern Front, where Soviet soldiers were being slaughtered. The experiment was a disaster. Almost 1 000 Canadians died and 500 were injured. Of the 5 000 Canadians, 2 752 remained at the beach, either dead or taken prisoner. Lessons learned at Dieppe were to save lives when D-Day was launched two years later. Invasion of Italy—On July 10, 1943, Allied forces, including a large contingent of Canadians, invaded the island of Sicily in southern Italy. Over the next months they slowly fought their way north through Italy. D-Day—On June 6, 1944, after years of training, the build-up of military hardware, and strategic planning, the day for the Allied counterattack to recapture Europe from German forces had come. Though a small nation, Canada played a key role. The fight for Normandy lasted about 11 weeks. Clearing the Coast—While other Allied troops headed for Germany, the Canadians fought their way up the coast, freeing up key port cities so that Allied supplies could be provided to inland troops. The Battle of the Scheldt, in the Belgium-Netherlands border area, was particularly fierce. The Rhine Offensive—On February 8, after conscripted Canadian troops arrived to bolster the weakened volunteer troops, Canadians launched an assault to capture an area along the border of Germany and the Netherlands. British and U.S. troops attacked Germany from farther south. Liberation of the Netherlands—In April, after crossing the Rhine, Canadian troops freed the Netherlands, bringing disaster relief to a starving population. Germany surrenders, May 4, 1945—In the following weeks, the Allies discovered the full horror of the war as they entered the death camps where almost two-thirds of Europe’s Jews had been killed. Activities 1. Make a timeline of the events leading up to war and the main events of the war. On your own, find three more key events of the Second World War to add to your timeline. 2. Which event of the Second World War do you think was a turning point, that is, an event that changed the course of history? Explain your thinking. CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 49 JUNO BEACH: SIXTY YEARS LATER YV Through Soldiers’ Eyes Further Research Since June 2004 represented the diamond anniversary of D-Day, a number of new books have been published, including Juno by Ted Barris, Thomas Allen Publishers; Juno Beach by Tim Sauders, McGillQueen’s University Press; and Juno Beach: Canada in World War II, a multimedia package including a CDROM, book and Web site, by Pierre Landry, Jack MacFadden and Angus Scully, Penguin Canada. Read the following reminiscences of four soldiers involved in the D-Day assault. Kelvin Mactier, Winnipeg, Manitoba, joined the Royal Winnipeg Rifles at the age of 21. He was one of the first to land on D-Day. We landed around 7 or 7:30 in the morning near Courseulles-sur-Mer. There was all kinds of gunfire coming towards us and everyone was shooting as they were running. I only got in about 20 or 30 feet [6 to 9 metres] when I was hit on the left side of the face by a bullet. There must have been a sniper in a church steeple to the left of us. It was just like getting hit on the head with a sledgehammer. It knocked me right down and I did a couple of somersaults. The bullet knocked out four teeth, went through my tongue and broke my jaw. I lay on the beach all day and kept passing out and coming to. What I remember most was men running by me the rest of the day. A lot of troops came in behind us. I didn’t have any fear of the Canadian Army being overrun or that we were going to lose. I knew we were in and that was it. . . . I fully recovered and was back with my regiment by September. (In Luke Fisher, D’Arcy Jenish, and Barbara Wickens, “Tale of War,” Maclean’s, June 6, 1994) Mervin Wolfe, Brandon, Manitoba, joined the Canadian army at the age of 19. At Juno he served as a forward operating observer with the 19th Army Field Regiment, an artillery unit. There were snipers firing at us from this big, old house right at the edge of the beach. There must have been half a dozen guys dead on the beach when I went in. As I ran up the beach, I was loaded up pretty heavily with my packsack, wireless set, a Sten gun, six rounds of ammunition and six hand grenades. One of the British commandos was running faster than me, probably because I was weighed down. He crossed in front of me and the moment he did he got hit. He went down and I tripped over him. I always said that bullet was meant for me instead of him. (In Luke Fisher, D’Arcy Jenish, and Barbara Wickens, “Tale of War,” Maclean’s, June 6, 1994) German soldier Franz Gockel defended the Normandy Coast on D-Day. In the beginnings, the ships lay at 20 kilometres, but the range slowly decreased. With unbelieving eyes we could recognize individual landing craft. The hail of shells falling upon us grew heavier, sending fountains of sand and debris into the air. The mined obstacles in the water were partly destroyed. . . . Suddenly the rain of shells ceased, but only for a very short time. Again it came. Slowly the wall of explosions approached, metre by metre, worse than before—a deafening torrent— cracking, screaming, whistling, and sizzling, destroying everything in its path. There was no escape, and I crouched helplessly behind my weapon. I prayed for survival and my fear passed. Suddenly it was silent again. There were six of us in the position, and still no one was wounded. A com- CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 50 rade stumbled out of the smoke and dust into my position and screamed, “Franz, watch out! They’re coming.” (Reprinted materials from Voices of DDay: The Story of the Allied Invasion Told by Those Who Were There, by Ronald J. Drez. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1994, as they appeared on www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/ dday/sfeature/sf_voices.html) George Frederick Johnson, Lance corporal with the Fort Garry Horse Regiment, participated in the second wave on Juno Beach. When I reached the tanks that first night, I saw some of the wounded coming back. We lost about 12, 13 guys from my regiment—killed on the beach that day. And I think there were another 15 or 16 wounded. I lost one of the kids I went to school with. He was killed on the beach along with another guy in his tank. Was I frightened? Continually. There were times when you hit the deck. But you’re so busy you don’t have time to reflect. I think war is a foolish thing to start with, but what are you going to do when you have the Germans running over smaller countries? And it looked like they would come across the Channel into England and take that country. That was when everybody said enough is enough. I was no hero. I just landed with the rest of them and went along with it. (Mark Zuehlke, “Canada’s Triumph at Juno,” Time Canada, May 31, 2004) Recreating the Past 1. In groups of four, each person can read out loud one of the quotations. Try to capture some of the drama and reality of the words. 2. Next, summarize, in your own words, what your soldier talks about. 3. Compare each man’s experience and how he viewed his experiences on June 6, 1944. 4. Write a personal response to one of the accounts of your own choosing. CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 51 JUNO BEACH: SIXTY YEARS LATER YV D-Day: Beginning of the End Quote “The first 24 hours of the invasion will be decisive . . . the fate of Germany depends on the outcome . . . for the Allies, as well as Germany, it will be the longest day.” —Erwin Rommel, the distinguished German field marshall in charge of the defence of Normandy Definition Mulberries were floating artificial harbours made in Great Britain in parts, transported across the channel, and then put together off the coast of Normandy. Each one was connected to shore with 10-kilometres of flexible steel roadways. Over the next eight weeks, the mulberries allowed the Allies to disembark the 1.5 million soldiers and 1.6 million tonnes of supplies required to sustain an invasion. The secrecy of the D-Day mission was of utmost importance. Many troops didn’t even know for sure that their trip to sea was not an exercise until they were out on the water. To confuse the enemy, General George S. Patton had created a fake preparation force near Dover, to make it look like the Allies intended to invade Pas de Calais. Movie-set builders created huge army encampments with thousands of wooden tanks. Days after the attack in Normandy, the Germans were still convinced that the real attack hadn’t yet occurred. On the evening of June 5, a code was broadcast over the BBC for the members of the underground in France. On hearing “The dice are on the table,” 5 000 French resistance fighters went into action, disabling electrical and telephone communication lines, and blowing up railway lines. Paratroopers (soldiers who use parachutes) went in first, at around midnight. They flew in on tiny Albermarles, twin-engine bombers converted to carry troops. The choice of plane was crucial. If the Germans spotted the bomber planes, they would think that they were just over Europe on another bombing raid. In the meantime, the Allied forces were crossing the channel from Southampton, Portsmouth, and Gosport toward Normandy. Bad weather plagued the mission, even delaying it by a day, but the bad weather served to put the Germans off their guard—who would be crazy enough to attempt an invasion in such bad weather? But attack they did at H-Hour: 6:30 a.m. The Americans The Canadians at Juno lost more men on that first day than anyone but the Americans at Omaha Beach. Omaha was a complete disaster because only two of the assigned 29 tanks made it to the beach, and they only lasted a few minutes. High cliffs overlooking the beach provided an excellent defensive position for the Germans, and the Americans paid a heavy price. On Utah Beach, the soldiers had less trouble on the beach but instead faced greater obstacles inland from rough and flooded terrain. The British The British at Gold Beach were to secure the site for a mulberry emplacement. They were also supposed to bridge the gap between the Americans to the south, and the Canadians to the north. Their success on the beach was largely due to their use of military vehicles designed specifically to clear the way through minefields and other barriers. The British at Sword Beach, farthest north, did not make their objective because of fierce fighting inland from German Panzer (Tank) Divisions. The Canadians The Canadians were older and a little less gung-ho than the soldiers from Britain and the United States. Not only had they been training for years for this mission, they knew about and feared another Dieppe disaster, in which so many of their fellow Canadians had been slaughtered. The Canadians were responsible for a 10-kilometre stretch of beach that CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 52 included the small fishing port of Courseulles-sur-Mer and the villages of Bernières-sur-Mer and St. Aubin. Heavy seas and a difficult landing site meant that the Canadians went in late— at 8:00 a.m.—to a wide, exposed beach where the Germans were prepared. It was a difficult landing. Some heavily laden soldiers stepped off their landing craft into deep water and promptly drowned. Tanks dropped into water that was too deep sank to the bottom. Bombers and naval guns had not managed to take out the German defences, so the men had to run through water and across beaches under a rain of bullets. The sound of enemy gunfire was continual, but the Canadians braved the maelstrom. Only half of the men to step off the first boats survived. These were the Royal Winnipeg Rifles, Le Régiment de la Chaudière, and the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment. One company of the Regina Rifles lost 92 of its 120 men on the beach. The situation was not as bad as Dieppe, although 375 Canadians died on that first day, and 628 were wounded. After making it onto the beach the soldiers had to stop the German guns. Tanks blasted shells at the German pillboxes. Infantrymen climbed right on top of them, tossing grenades through the firing slits or kicking in the back doors to fight with bayonets and rifles. Although they arrived on the beach last, the Canadians got farther inland than any other D-Day unit. Worse was to come, when the Canadians met the soldiers of the 12th SS— Hitler Youth—at the Carpiquet airfield outside Caen. The fighting was brutal. Some Canadians were captured in Normandy, becoming prisoners of war. Of these, 144 Canadians were shot after capture. In the first six days of the Normandy campaign 1 017 Canadian soldiers were killed. More than 5 000 were dead by the time the campaign ended. By the end of the war, 42 000 Canadian soldiers had made the greatest sacrifice for their country and for freedom. A Day for Canada to Remember Partly because of our losses, and also because of our hard-fought success, a great thing happened for Canada on DDay. It seemed to many Canadians that we stood tall as a David among the Goliaths of Britain and the United States. Despite our small population, we fought alongside our partners to wrest freedom from the brink. Many Canadians began to realize that we might participate fully as a leader in the world—we had earned that place as a defender of freedom on Juno Beach. Research Activities 1. On a blank map of Europe, locate and label Portsmouth, Southampton, Normandy, Caen, Pas de Calais, and Berlin (capital of Germany). Explain why the Germans would have expected an attack on Pas de Calais instead of Normandy. 2. Research the events at one of the five beaches the Allied forces attacked on D-Day. Write a one-page synopsis of the day’s efforts. CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 53 JUNO BEACH: SIXTY YEARS LATER YV Juno Beach Centre Further Research Use these sites to complete the research activity: www.normandie memoire.com (history section) www.canadianbattleof normandyfoundation.ca www.waramps.ca/ military www.vac-acc.gc.ca/ general/ sub.cfm?source=history/ secondwar D-Day veteran Garth Webb, of Burlington, Ontario, served with the Royal Canadian Artillery. In 1994, to mark the 50th anniversary of D-Day, he visited Europe, where he was deeply moved by the warm response the Dutch people gave to the Canadians who had liberated their country. Even those born long after the war appeared grateful that people from so far away would face danger to free them. Webb decided that the Canadian contribution to the war should be better recognized elsewhere, and so began his mission to create a museum and memorial in Normandy. After many years of lobbying and raising private and public money for the project, Webb and his partner, Lise Cooper, finally realized their dream in the form of the Juno Beach Centre, which overlooks the beach that the Canadians stormed so many years ago. This museum and education centre in Courseulles-sur-Mer opened on June 6, 2003, and it presents the Canadian contribution to the Allied effort during the Second World War. If you can’t visit the real museum, you can always visit the Juno Beach Centre Web site at www.junobeach.org. The site gives information about the goals of the museum. It also gives you a virtual tour of the museum in Normandy, and has an excellent list of Web links for anyone interested in learning more about the Canadian war effort. The second arm of information on the Web site, Canadians in the Second World War, lists four different types of information: • people • events • arms and weapons • interactive centre The interactive centre is quite informative, with interactive maps that include: • the Allied, Axis, and neutral countries over time • how the war progressed, including Canadian troop movements and Canadian frontlines • what went on in different theatres of war—for example, where German Uboats were sunk • animations that demonstrate the technology of war—for example, how minesweeping works Research Skills 1. Form groups of four to investigate the four Web sites in the margin box. Each of you can assess one of the four sites. Answer the following questions about your site: • What organization runs the site? • How recent is the information? When was the site last updated? • What kinds of information can you find at the site? • Did you find any examples of bias on the site? • Are statements backed up by facts? 2. Find one other Web site that you could use to research Canada’s contribution during the Second World War. Analyze it using the questions provided in Question 1. Would you recommend this site for research? Why, or why not? CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 54 YV JUNO BEACH: SIXTY YEARS LATER YV Remembering Activity Quote Globe and Mail newspaper reporter Roger Hall remarks about the ways we remember the sacrifices made for us: They might be symbols, but the mourning and emotions they trigger are real. Some say that one can heal wounds by forgetting, but it seems to me that healing can be better achieved by remembering. — The Globe and Mail, June 5, 2004 Besides the Juno Beach Centre, here are other ways that Canadians and the French commemorate the many acts of courage made by Canadian soldiers on D-Day. • The Canadian War Cemeteries were perhaps the first commemoration. Benysur-Mer, five kilometres inland, holds 2 043 Canadian dead. A further 2 728 rest at Brettevile-sur-Laize. The Canadian names on the white crosses are a mosaic of French, English, Ukrainian, German, Polish, Italian, Jewish, First Nations, and more. • A Canadian Sherman tank is parked permanently in the village square in Courseulles-sur-Mer. • Canadian Battlefields Foundation created a memorial garden on the grounds of Le Mémorial du Caen, France, to recall the Canadian participation in the Battle of Normandy. You can see it at www.canadianbattleofnormandyfoundation.ca/memorial_garden.htm •␣ The Sixtieth Anniversary Celebrations, in 2004, which transpired over 80 days, the same length of time that it took to secure Normandy in 1944. Each town held celebrations in turn, to correspond to the day when it was liberated 60 years earlier. Activities 1. How do each of the above memorials help us remember what Canadian soldiers accomplished on Juno Beach? 2. In what other ways do we remember and honour our veterans? 3. Think of three other ways that Canadian young people like yourself could help remember Juno Beach. 4. You don’t need to go to France or have a lot of money to help others remember what Canadian soldiers have accomplished. Design a memorial of your own for the Canadians who fought in one of Canada’s great battles during the Second World War. This could be a poster, a “newscast,” a pantomime, or any other means of presentation. Work in a group to research one of the following battles. Then choose a way to memorialize the event and work together to create it. • D-Day Battle of Normandy (Operation Overlord), June 6, 1944 • Battle of Vimy Ridge, April 9, 1917, in which 5 000 Canadians died and 15 000 were injured in their push to take Vimy Ridge, the linchpin of the German defence system in northern France in the First World War • Dieppe Raid (Operation Jubilee), August 19, 1942, in which 4 000 Canadians and a handful of Britons made a courageous attempt to breach the Atlantic fortress in France CBC News in Review • October 2004 • Page 55