* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Preview the material

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

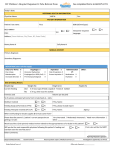

ASPIRATION: RISKS, RECOGNITION, AND PREVENTION DANA BARTLETT, RN, BSN, MSN, MA Dana Bartlett is a professional nurse and author. His clinical experience includes 16 years of ICU and ER experience and over 20 years of as a poison control center information specialist. Dana has published numerous CE and journal articles, written NCLEX material, written textbook chapters, and done editing and reviewing for publishers such as Elsevire, Lippincott, and Thieme. He has written widely on the subject of toxicology and was recently named a contributing editor, toxicology section, for Critical Care Nurse journal. He is currently employed at the Connecticut Poison Control Center and is actively involved in lecturing and mentoring nurses, emergency medical residents and pharmacy students. ABSTRACT Both national safety and health facility protocol guide nursing practice in the area of aspiration risk precaution and treatment. Multiple factors influence the potential for aspiration risk and complications stemming from silent and major aspiration episodes. Nursing interventions in acute care and long-term settings involve recognizing the potential for aspiration and implementing preventive and timely treatment measures when an issue of aspiration occurs, such as aspiration pneumonia and its sequela. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 1 Continuing Nursing Education Course Planners William A. Cook, PhD, Director, Douglas Lawrence, MA, Webmaster, Susan DePasquale, MSN, FPMHNP-BC, Lead Nurse Planner Policy Statement This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the policies of NurseCe4Less.com and the continuing nursing education requirements of the American Nurses Credentialing Center's Commission on Accreditation for registered nurses. It is the policy of NurseCe4Less.com to ensure objectivity, transparency, and best practice in clinical education for all continuing nursing education (CNE) activities. Continuing Education Credit Designation This educational activity is credited for 2.5 hours. Nurses may only claim credit commensurate with the credit awarded for completion of this course activity. Statement of Learning Need Risk factors for aspiration are a national safety concern in acute care and long-term care facilities. Nurses provide the primary care for patients at the bedside where the use of screening tools and protocol to recognize patient risk and an aspiration event is most crucial. Although aspiration can often be a benign event, the risk of aspiration in elderly and acutely ill patients, such as those with mental status nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 2 changes, poses a severe health concern with significant morbidity and mortality if standards of care are not appropriately observed. Course Purpose To provide knowledge about aspiration risk, prevention and treatment in acute care and long-term care settings. Continuing Nursing Education (CNE) Target Audience Advanced Practice Registered Nurses and Registered Nurses (Interdisciplinary Health Team Members, including Vocational Nurses and Medical Assistants may obtain a Certificate of Completion) Course Author & Planning Team Conflict of Interest Disclosures Dana Bartlett, RN, BSN, MSN, MA, William S. Cook, PhD, Douglas Lawrence, MA, Susan DePasquale, MSN, FPMHNP-BC -all have no disclosures Acknowledgement of Commercial Support There is no commercial support for this course. Activity Review Information Reviewed by Susan DePasquale, MSN, FPMHNP-BC Release Date: 4/29/2016 Termination Date: 4/29/2019 nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 3 Please take time to complete a self-assessment of knowledge, on page 4, sample questions before reading the article. Opportunity to complete a self-assessment of knowledge learned will be provided at the end of the course. 1. Aspiration is defined as a. b. c. d. 2. The most important protection against aspiration is the a. b. c. d. 3. epigastric reflex. nasal reflex. gag reflex. Babinski reflex. Which of these prevents foreign objects from entering the larynx? a. b. c. d. 4. infection of the lungs from nasal secretions. movement of a foreign substance into the lungs. abnormal or difficult swallowing. the absence of a gag reflex. The The The The uvula pharynx esophageal sphincter epiglottis True or False: Approximately 30% of people do NOT have a functioning gag reflex. a. True b. False 5. Which of the following are common causes of aspiration? a. b. c. d. Myocardial infarction and hypertension Diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease Stroke and dysphagia Irritable bowel syndrome and general anesthesia nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 4 Introduction Aspiration is defined as the movement of a foreign substance into the lungs. Aspiration is very common and it can cause significant and serious complications. All nurses working in acute and long-term care settings need to be able to recognize factors that increase the risk for aspiration, know which patients are most likely to aspirate, and to understand the signs and symptoms of aspiration. These are essential aspects of safe and appropriate nursing care to avoid an adverse patient event. Swallowing And The Gag Reflex Aspiration is intimately related to swallowing and the gag reflex so to understand aspiration the nurse must be familiar with these normal physiological functions. The cough reflex is also involved in aspiration and that will be discussed briefly in another section of this learning module. Upper Gastrointestinal Tract and Associated Structures Swallowing is the coordinated movement of food or liquids from the mouth to the stomach. It will be explained here in terms of swallowing solid food but the process is essentially the same for liquids. Swallowing can best be understood by dividing it into two phases: voluntary and involuntary. These will be discussed in context of the nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 5 upper gastrointestinal tract structures known to be involved during the process of swallowing.1 Finally, aspiration prevention will be reviewed. The Gastrointestinal Tract The gastrointestinal tract starts with the mouth, which is also called the oral cavity. It then descends into the pharynx, esophagus and into the stomach as depicted in the following table.1 Table 1: The Upper Gastrointestinal Tract Oral Cavity ↓ Pharynx ↓ Esophagus ↓ Stomach The sections of the upper gastrointestinal tract are described in greater detail in the following section.1 Oral Cavity The oral cavity is the beginning of both the respiratory tract and the gastrointestinal tract. In terms of swallowing the primary function of the oral cavity is to begin the digestion of food and to break down food into manageable sizes. Pharynx nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 6 The next section of the gastrointestinal tract is the pharynx, a relatively short tube made of muscle and connective tissue that is located behind the larynx. The pharynx connects the oral cavity to the esophagus. The pharynx is further comprised of the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx. The primary functions of the pharynx are to allow passage of food and liquid into the esophagus and air into the trachea. Esophagus The esophagus is a thick-walled tube of muscle and cartilage that is located behind the larynx and the trachea. The esophagus connects the pharynx to the stomach and like the pharynx, its primary function is to allow for the passage of food and liquids. The esophagus has two sphincters, the upper and lower esophageal sphincters. A sphincter is a ring of muscle that can open and close and there are many sphincters throughout the body; the anal sphincter is an example. The upper esophageal sphincter is located at the junction of the pharynx, and the lower esophageal sphincter is located at the juncture of the esophagus, where it meets the stomach to complete the passage of food or fluids. The esophageal sphincters are not under voluntary control and except during swallowing, they are normally closed. Gastrointestinal Tract and Associated Structures The associated structures to the upper gastrointestinal tract are described below in greater detail. Epiglottis nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 7 The epiglottis is a flap of cartilage that is attached to the upper part of the larynx. One end of the epiglottis is attached to the larynx (this attachment can be thought of as a hinge) and the other end projects backwards up and behind the tongue. The epiglottis has a vital role in normal swallowing and the prevention of aspiration, and this will be discussed later on in this module. The epiglottis is above the glottis, which is the opening between the vocal cords. Larynx The larynx is the initial section of the respiratory tract. It is a short tube of muscle and cartilage that begins in the oral cavity and connects to the trachea (commonly known as the windpipe). The larynx is relevant to this module because the larynx is where coughing is initiated and coughing is an important protective reflex that keeps foreign bodies from entering the lungs. Swallowing As mentioned above, swallowing can best be understood by dividing it into two phases: voluntary and involuntary, which are explained further here. Voluntary Phase Swallowing is for the most part an automatic process; we do not have to think about swallowing as it happens. However, the initial phase of preparing the food for swallowing and the beginning of swallowing is under voluntary control. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 8 The voluntary phase (also called the oropharyngeal phase) of swallowing begins in the oral cavity by lubrication of the food with saliva and digestive juices and chewing the food into small pieces that can pass through the upper parts of the gastrointestinal tract; these small pieces of food are called boluses. Involuntary Phase After food has been chewed and lubricated, the lips close to seal the mouth and the tongue moves the bolus to the back of the oral cavity and into the oropharynx. At this point the involuntary phase (also called the esophageal phase) of swallowing begins. As the food bolus or liquid reaches the oropharynx a series of coordinated movements begin to push the food or liquid smoothly through the upper gastrointestinal tract and into the stomach. When examined closely, this process has many steps but it can be explained quite simply. Although the swallowing process is presented here stepby-step, all of these actions happen essentially at the same time. Table 2: The Process of Swallowing 1. The pressure of the food bolus in the pharynx causes the muscles of the pharynx to contract and to move the food away from the mouth and into the pharynx. 2. The uvula contracts and covers the opening of the nasopharynx, preventing food from entering the nasal passages. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 9 3. Laryngeal movement: Once the food bolus or liquid reaches the back of the oral cavity, the larynx moves upward. This helps close the glottis and prevents food from passing through the vocal cord and into the trachea. 4. Epiglottis movement: At the same time that the larynx is moving upward to close the glottis, the epiglottis swings down and covers the opening of the larynx, acting like a cover. This prevents food or liquid from entering the trachea. 5. Sphincter relaxation: The esophageal sphincter relaxes, providing access to the esophagus. 6. Peristaltic action: Once the food or liquid enters the esophagus it is moved along by involuntary rhythmic muscles actions called peristalsis. Because the esophagus is essentially a closed tube, pressure on any part of the esophagus will move food or liquid in the direction of least resistance - in this case, towards the lower esophageal sphincter and the stomach. A useful way to think of this is to imagine squeezing an open tube of toothpaste; when you do so the contents will be moved out through the opening and peristaltic contractions in the esophagus function in the same way. 7. The lower esophageal sphincter relaxes and allows for passage of the food bolus or liquid into the stomach. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 10 During the process of swallowing, other physiological actions that involve the oral cavity, the pharynx, the larynx, or the esophagus cannot be done. When a person is swallowing he or she cannot inhale, exhale, talk, vomit, or cough. When the process of swallowing is reviewed, two things are prominent and have particular relevance to the topic of aspiration. 1. The gastrointestinal tract and the respiratory tract are in close proximity; at certain points there is very little that separates them. 2. Swallowing requires the coordinated action of many muscles, nerves, and reflexes; it is a relatively complicated act. Given these two points, it becomes apparent that there is considerable potential for food or liquid to be aspirated, and that there are many steps in the process of swallowing that can break down and put a patient at risk of aspiration. Gag Reflex And Cough Reflex The gag reflex and the cough reflex protect the lungs from aspiration and entry of foreign objects. The gag reflex involves the oral cavity and the upper part of the gastrointestinal tract; the cough reflex involves the upper part of the respiratory tract. The gag reflex, which is more formally called the pharyngeal reflex, is the most important protective mechanism for the prevention of aspiration and it will be discussed in detail here.1 The gag reflex occurs when a foreign object touches the roof of the mouth, the back of the tongue, the areas around the tonsils or the nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 11 uvula, or the oropharynx. When a person swallows, food and liquids contact these areas but the automatic closing of the epiglottis prevents aspiration from occurring. This protective mechanism is absent during a potential aspiration situation but the gag reflex takes over and stops foreign objects from entering the lungs. Nerve endings located in the roof of the mouth, the back of the tongue, etc., are stimulated by the physical contact with food or fluid and this stimulation initiates very strong, forceful contractions of the pharynx, which expels the foreign object. The patient experiences the gag reflex as coughing, choking, and gagging. Learning Break: An easy way to imagine the gag reflex is to think about an experience we have all had, one that is commonly called “having something go down the wrong way.” A piece of food or some liquid reaches the back of your mouth and you begin to gag and cough. An intact functioning gag reflex is essential to prevent aspiration. However, it has been estimated that the gag reflex is absent in almost 30% of the population and some people may have a gag reflex but it is not very strong. In addition, there are many diseases and medical conditions that can temporarily or permanently damage the gag reflex, making that person susceptible to aspiration. The cough reflex is also important for preventing aspiration. The primary function of the larynx and trachea is to move air into the lungs and the respiratory tract and any foreign substance that enters the airways interferes with respiration and is a potential cause of infection. Nerve endings located nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 12 on the larynx and the trachea becomes stimulated when a foreign body enters the larynx or trachea. A forceful cough is produced, which aids the foreign object to be expelled. Aspiration: Causes, Signs, Symptoms, Consequences Aspiration occurs when the gag reflex and the cough reflex fail to prevent a foreign substance from entering the lungs. The common conception of aspiration is that it is an abnormal and dramatic pathologic event that causes coughing, choking, and a serious complication such as pneumonia. This is certainly true for some aspiration events but aspiration is actually a common occurrence and it may not result in harm. Studies have shown that at least one-half of all adults aspirate during sleep and the aspiration does not wake them up or cause signs or symptoms. Aspiration happens to normal, healthy adults who have a functioning gag reflex. They aspirate very small amounts of saliva, mucous, and possibly gastric juices. The aspirations that result in serious harm occur in a very different population, under very different circumstances, and with potentially serious consequences. Why and how these aspirations become harmful are highlighted below.3,4,7,8 Volume In patients who may suffer a harmful aspiration there is often a large volume that enters the lungs. An example of this would be the patient who has aspirated tube feedings. A milliliter or two would be tolerated but 30 ml or more, for example, would cause signs and symptoms. However, serious aspiration can occur from a small volume or amount. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 13 Substance If the aspirate contains infectious bacteria the patient may develop aspiration pneumonia. Frequency Aspirations occurring repeatedly expose the respiratory tract/lungs to more frequent stress and the patient has less time to recover. Patient Issues There are many individual factors that influence how often aspirations occur and whether such events cause complications. For example, patients with a decreased level of consciousness, compromised immune system, or a respiratory illness, i.e., pneumonia or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) that decreases the blood oxygen level. In all of these situations, aspiration and/or harm from aspiration is more likely to occur. There are many causes of aspiration, as shown in Table 3 below; however, this list is not all-inclusive. Table 3: Causes of Aspiration Cerebral vascular accident (Stroke) Drug or alcohol overdose Dysphagia Excessive production of oral secretions General anesthesia Grand mal seizure Mechanical ventilation Nasogastric feedings nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 14 Neurologic diseases Prolonged vomiting Sedative, hypnotic, or opioid medications Tracheostomy Traumatic brain injury In addition to the above list of identified causes of aspiration being not all-inclusive, there is also some overlap; for example, many people who have a stroke develop dysphagia. This list can certainly be studied and referred back to from time-to-time, however, it is more useful to view these causes of aspiration as having similarities. Understanding these similarities will help to identify patients who are at risk for aspiration. These similarities are elucidated below. The patient has a depressed level of consciousness. Someone who has a depressed level of consciousness often has a weak or absent gag reflex. Often, in such a scenario the patient is described as someone not having the ability to “protect the airway.” This can happen to a patient who has had a stroke, experienced a seizure, or following a drug overdose. Protective reflexes are absent or compromised. Examples of this would include a patient who 1) has been endotracheally intubated or who has a tracheostomy, 2) had placement of a nasogastric feeding tube, or 3) has dysphagia. (Dysphagia will be discussed later in the module). Experienced nurses know that when patients have a depressed level of consciousness there is also a loss of protective reflexes; the two nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 15 frequently go together. For example, a patient who has had a stroke may be comatose and have a damaged gag reflex.6 Learning Break: Dysphagia is a medical term that means difficulty in swallowing. Common neurological problems such as Alzheimer’s disease, stroke, and traumatic brain injury frequently cause dysphagia and dysphagia is a significant risk factor for aspiration. Dysphagia is very common; the authors of a recent article in the medical journal Chest noted that dysphagia is present in at least 30% of all hospitalized patients. Unfortunately, dysphagia often goes unrecognized. Aspiration Signs And Symptoms The signs and symptoms of aspiration can be subtle and very clear or some patients can aspirate and initially be asymptomatic. The obvious signs and symptoms of aspiration are coughing, choking, and difficulty breathing and they often occur after a situation that puts the patient at risk. For example, a patient who recently had a stroke and is taking fluids by mouth for the first time begins to cough and gasp. Experienced nurses recognize this as a situation with the potential for aspiration risk and of course coughing and gasping cannot be missed. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 16 It is difficult to recognize aspiration when aspiration is slight, if the signs and symptoms are minor, or if the patient is initially asymptomatic.12 In these situations the nurse must remember who is at risk for aspiration and be on the alert for clues that an aspiration has happened. Signs and symptoms of aspiration are listed in Table 4 below. Table 4: Signs and Symptoms of Aspiration Change in consciousness, especially depressed consciousness Decreased oxygen saturation as measured by pulse oximetry Excessive drooling Fatigue Fever Increased sputum production Persistent, mild cough Rapid breathing Tachycardia Vomiting soon after meals Of course, signs and symptoms of aspiration listed above are nonspecific. There are many reasons why a patient may have a fever or a rapid pulse. If these signs are present in a patient who has risk factors for aspiration, then the possibility should be investigated. Learning Break: Asymptomatic aspiration is also called silent aspiration, and it is nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 17 especially worrisome. It cannot be detected without specialized testing, and patients who have silent aspirations are much more likely to develop aspiration pneumonia. Silent aspirations are not rare. One study found that 25% of all patients who had a confirmed, documented aspiration had experienced a silent aspiration. The Consequences Of Aspiration Aspiration can cause airway obstruction and interfere with ventilation. It can also cause an inflammation of the lungs called chemical pneumonitis, aspiration pneumonia, or a combination of these conditions. This section discusses known risks and complications of aspiration.10,11,12 Aspiration pneumonia is perhaps the most common complication of aspiration. It occurs when a patient aspirates bacteria or other microorganisms from his or her oral cavity, nasal passages, or upper stomach. These microorganisms are part of the normal flora of the upper respiratory tract and the gastrointestinal tract, but if they enter the lungs they can multiply and then are not benign. Aspiration pneumonia can develop if these oral, nasal, or gastric nasal secretions contain a large number of microorganisms, if the aspirations are frequent, or if the patient is susceptible to a respiratory infection. It is important to remember that the size of the aspiration is not important. Aspiration pneumonia can occur even after a very small aspiration, and aspirations can be silent. Just as importantly, nurses should be aware that pneumonia occurs in approximately one-third of all patients who aspirate. The exact incidence of aspiration pneumonia nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 18 is not known but it is a relatively common problem. It is especially prevalent in the elderly population; quite commonly in the elderly who have dysphagia and in elderly people who are hospitalized. For elderly who are hospitalized, aspiration pneumonia is also very dangerous. One study found the mortality rate of hospital-associated aspiration pneumonia to be almost thirty percent. The signs and symptoms of aspiration pneumonia vary considerably and depend on how recently the aspiration happened, the patient’s basic state of health, and the virulence of the microorganism. Common clinical problems that are seen are drowsiness, fever, rapid breathing, and tachycardia. If the patient is elderly and dehydrated, he or she may be hypotensive, as well. It is also possible for the patient to have relatively mild signs and symptoms for a few days as the aspiration pneumonia develops. Aspiration pneumonia is diagnosed by examining the patient, by recognizing risk factors for aspiration, and most definitively by chest x-ray. Laboratory studies, including culture of sputum have limited usefulness in diagnosing aspiration pneumonia. Aspiration pneumonia is treated with antibiotics and fluids. Prevention Of Aspiration As with any medical problem, disease prevention is far better than treatment. Aspiration prevention is considered to be a key component of safe and appropriate healthcare, and it involves identifying patients who are at risk and then using practical methods to ensure that patients do not aspirate.10,11,12 nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 19 Identifying Risk for Aspiration: Screening Methods Aspiration prevention is considered to be a key component of good healthcare. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) is an agency of the National Institutes of Health, and the AHRQ recommends as one of its 30 Safe Practices for Better Health Care that all patients be screened for aspiration. To quote the AHRQ: “Upon admission, and regularly thereafter, evaluate each patient for the risk of aspiration.”2 Evaluating stroke patients within 24 hours of admission for their risk of aspiration and the presence of dysphagia is also typically recommended. Prevention of aspiration begins with recognizing patients who are at risk for this problem and this has been shown to be both simple and difficult. The simple part is identifying which patients are likely to suffer an aspiration (as covered earlier on in this learning module). If the answer is Yes to any of the screening questions highlighted in the table below then the patient is at risk for aspiration. Table 5: Basic Screening for Aspiration Risk Is the patient elderly? Is she or he receiving any medications that can cause sedation? Does the patient have a neurological disease or disorder? Does the patient have excess secretions? Was general anesthesia recently used? Does the patient have obvious difficulty eating/swallowing? Is he or she unable to sit upright? Has the patient has a prior aspiration? Does she or he have a history of dysphagia? Does the patient have a depressed level of consciousness? nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 20 This basic assessment should be done for all patients, and for patients who are especially susceptible to aspiration it should be repeated from time to time. Most healthcare facilities will have an aspiration screening tool and a protocol for how and when to use it. There are bedside and technical-based screening methods that can be used for detecting aspiration, evaluating aspiration risk, and for detecting one of its most common causes, dysphagia. Unfortunately, there is no universal agreement as to which one is best and when they should be used and that is the part of aspiration and dysphagia screening that is difficult. Explaining all of these screening methods is beyond the scope of this learning module but commonly used ones are listed in Table 6. The EAT-10 can be done at the bedside without specialized equipment and is briefly discussed here. Table 6: Screening Methods for Detecting Aspiration/Dysphagia Barium swallow test EAT-10 Endoscopy Video-fluoroscopic evaluation (VSE) Water swallow test All of the screening methods listed in Table 6 (except the EAT-10) are technical tests while the EAT-10 is a questionnaire that can be used to determine the need for more complicated screening. The EAT-10 asks the patient to respond to these 10 statements. Table 7: The EAT-10 Questionnaire 1. My swallowing problem has caused me to lose weight. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 21 2. My swallowing problem interferes with my ability to go out for meals. 3. Swallowing liquids takes extra effort. 4. Swallowing solids takes extra effort. 5. Swallowing pills takes extra effort. 6. Swallowing is painful. 7. The pleasure of eating is affected by my swallowing. 8. When I swallow food sticks in my throat. 9. I cough when I eat. 10. Swallowing is stressful. The answers to the questions are scored on a scale from 0 – 4 (0 = no problem to 4 = severe), and if the total score is 3 or higher the patient may have a swallowing problem and more aggressive evaluation should be considered. Practical Methods For Aspiration Prevention If a patient has been identified as being at risk for aspiration or if the patient has aspirated, then practical methods designed to prevent this from happening should be started. Basic steps to prevent aspiration are reviewed are highlighted here.14,15 The first step nurses should follow is to use the aspiration evaluation protocol that their healthcare facility has adopted. Nurses should also keep in mind the screening questions that are listed above. Specific measures for preventing aspiration include: 1) patient positioning, 2) oral care; 3) assessment of nasogastric tube placement; 4) tube feeding technique; 5) measuring residual gastric volume; and, 6) avoiding the use of sedating drugs. Each healthcare facility will use these preventive measures in a different way and some of them may not be used at all, so it is not possible to provide strict, definitive guidelines for their use. Nurses nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 22 should follow the protocols established for their workplace and when in doubt they should review facility protocols with a nursing supervisor. Nurses are also key agents in their workplaces to advocate for best practice protocols and improved standards of safe and appropriate practice relative to aspiration risk precaution. The following patient care interventions are recommended practice to prevent aspiration in acute care and long-term care health facilities. Positioning Elevating the head of the bed is a very effective method for preventing aspiration. Lying flat or with the head slightly elevated increases the possibility of aspirating, especially so if a patient has an absent or weak gag reflex or is receiving feedings by a nasogastric tube. Keep in mind that one of the first things people do when food or liquid “goes down the wrong way” is to stand up. Elevating the head of the bed at 30°-45° for patient safety is typically recommended, however the exact degree to which the head of the bed should be elevated is also generally determined by health facility protocol.10 Oral Care Entry of oral, nasal, and gastric secretions into the lungs cause aspiration pneumonia. Rigorous attention to oral care and possibly the use of antiseptic mouth rinses that contain chlorhexidine are often used as ways to reduce the number of microorganisms in the oral cavity and prevent aspiration pneumonia. Chlorhexidine is an antibacterial agent and a 0.12%-0.2% solution can be applied to a sponge to swab the patient’s mouth four times a day. The frequency of nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 23 chlorhexidine use and the protocol may vary from hospital to hospital.13,16 Assessment of Nasogastric Tube Placement Nasogastric tubes can easily become misplaced, putting the patient at risk for aspiration. Frequent assessment of the proper position of nasogastric tube placement is a responsibility of the nurses in terms of preventative technique and long-term management. The management of tube feeding and aspects of the nursing assessment to prevent aspiration are reviewed below.5,6,9 Tube Feeding Technique If a patient is receiving tube feedings and is at risk for aspiration, tube feedings should be given at the prescribed rate. The nurse should not increase the tube-feeding rate unless there is a specific order to do so and should never administer a tube feeding as a bolus. Bolus feeding increases the risk for aspiration. Measuring Residual Gastric Volume A technique that has traditionally been used to prevent aspiration in patients who are receiving nasogastric feedings is measuring residual gastric volume. After a tube feeding, the amount of enteral nutrition liquid that is still in the stomach is measured. If the residual is above a certain amount then it is assumed that the patient’s gastrointestinal tract is not properly absorbing the liquid nutrition and the excess volume puts the patient at risk for aspirating. This technique may be helpful for certain patients but recent research has questioned its usefulness. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 24 Avoid Sedating Drugs The use of sedating drugs increases the risk of aspiration. Administering these medications is a nursing responsibility. Additionally, the nurse should be assessing patients for excessive drowsiness caused by sedatives, analgesics, and other drugs that can cause central nervous system depression and reporting these adverse effects if they occur to the patient’s primary medical provider. Case Scenario: Aspiration Pneumonia Mrs. B is an 86-year-old female who has just been discharged from the hospital and admitted to a long-term care facility. She recently suffered a stroke that left her with significant weakness of her left arm and leg. She is unable to walk but with some assistance she can perform some simple activities of daily living and her mental status and speech are completely intact. The patient has been depressed and occasionally mildly agitated as she tries to adjust to her limitations. In addition her appetite has been poor and for the past two days she has refused to eat, telling the staff that food “makes me sick.” She also complains of persistent pain in her left side. Because of these developments the physician ordered the patient to be given a low dose of fluoxetine, a commonly used anti-depressant. The physician also requested an orthopedic and physical therapy consult and while awaiting the results of those evaluations, she prescribed a nonnarcotic analgesic, tramadol. Finally, after extensive discussions with the patient and with her acceptance, a small nasogastric tube was inserted and enteral tube feedings were begun. It was understood that the feeding tube would be in nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 25 place for only a short period of time. Several days after the fluoxetine, tramadol, and tube feedings were started the patient’s condition was improved. Her mood was brighter, her pain was decreased, and she seemed to have more energy. Mrs. B’s pain was diagnosed as osteoarthritis, she was able to start physical therapy. Plans were made for to move Mrs. B (within a few weeks) to a relative’s house, albeit with the support of visiting nurses. However, after a week of clinical gains the staff began to notice some mild regressions. The patient was sleeping more and had less energy during the day, although there were periods of time in which she seemed normal. She also had a fever of 100.1° F, but this only occurred once and the fever responded to fluids and a dose of acetaminophen. On the seventh day of her tube feedings, Mrs. B was noted to have a fever of 102.7° F and her respiratory rate was 24. Shortly after being assisted from her bed to a chair, Mrs. B had several forceful, productive coughs and the nurse saw undigested tube feeding residue in the patient’s sputum. The physician was notified, a chest x-ray was done, and it was clear that Mrs. B had aspirated and had pneumonia. In the above scenario, the patient had obvious risk factors for an aspiration. She had recently had a stroke, was prescribed several medications that are known to cause central nervous system depression, a nasogastric tube was in place, and she was receiving enteral tube feedings. The clinical course the patient experienced was fairly typical, with some subtle signs of silent aspiration being present before it became clear that some of the tube feeding and gastric juices had entered her lungs. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 26 Summary Episodes of aspiration can be sudden and dramatic, but aspirations can also be very minor and the patient may remain asymptomatic, the socalled silent aspiration. The causes of aspiration are many, and some of the common ones have been reviewed here. Although the causes of aspiration are all distinct, separate problems they share two common characteristics: the patient is likely to have a depressed level of consciousness and the protective mechanisms that prevent aspiration are absent or compromised. Dysphagia in particular is very common and a significant cause of aspiration. Aspirations can cause serious medical problems, especially if there is a large volume that has been aspirated and when the aspirate contains a large number of infectious bacteria. When aspirations occur repeatedly the patient is more predisposed to pulmonary complications. Nurses need to be informed of the most common complication of aspiration aspiration pneumonia - as well as protocol to prevent its occurrence, common signs and symptoms, and treatment. Screening for aspiration is a vital part of care that every nurse working in acute and long-term care facilities should implement in their work settings. Both national standards of safe and appropriate practice and health facility protocol to prevent, recognize and treat aspiration should guide nursing actions during the course of patient care. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 27 Please take time to help NurseCe4Less.com course planners evaluate the nursing knowledge needs met by completing the self-assessment of Knowledge Questions after reading the article, and providing feedback in the online course evaluation. Completing the study questions is optional and is NOT a course requirement. 1. Aspiration is defined as a. b. c. d. infection of the lungs from nasal secretions. movement of a foreign substance into the lungs. abnormal or difficult swallowing. the absence of a gag reflex. 2. The most important protection against aspiration is the a. b. c. d. epigastric reflex. nasal reflex. gag reflex. Babinski reflex. 3. Which of these prevents foreign objects from entering the larynx? a. b. c. d. The The The The uvula pharynx esophageal sphincter epiglottis 4. True or False: Approximately 30% of people do NOT have a functioning gag reflex. a. True b. False 5. Which of the following are common causes of aspiration? a. Myocardial infarction and hypertension b. Diabetes and Alzheimer’s disease nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 28 c. Stroke and dysphagia d. Irritable bowel syndrome and general anesthesia 6. An aspiration that does not cause obvious signs or symptoms is known as a a. b. c. d. silent aspiration. benign aspiration. minor aspiration. simple aspiration. 7. Which of the following is a common complication of aspiration? a. b. c. d. Hyperglycemia Pulmonary edema Fever Pneumonia 8. Common signs and symptoms of aspiration may include: a. b. c. d. Bradycardia and drowsiness. Fever and rapid breathing. Hypertension and hypoglycemia. Hypotension and agitation. 9. Patients should be screened for aspiration risk a. b. c. d. on admission and the as needed. when they are being discharged. if they have signs and symptoms of aspiration. if they are elderly females (elderly males don’t need screening). 10. Which of the following is a recommended method for preventing aspiration? a. b. c. d. Keeping the head of the bed level Administering tube feedings as a bolus Keeping the head of the bed elevated Deep breathing exercises 11. In addition to the gag reflex, the __________ is also important for preventing aspiration. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 29 a. b. c. d. cough reflex nasal reflex pharyngeal reflex Babinski reflex 12. Swallowing is the voluntary coordinated movement of food or liquids from the mouth to the stomach. a. True b. False 13. The oral cavity is the beginning of a. b. c. d. the gastrointestinal tract. the respiratory tract. the respiratory tract and gastrointestinal tract. None of the above 14. The _____________ is a thick-walled tube of muscle and cartilage that is located behind the larynx and the trachea. a. b. c. d. gastrointestinal tract. esophagus epiglottis duodenum 15. The ________________ is located at the juncture of the esophagus, where it meets the stomach to complete the passage of food or fluids. a. b. c. d. lower esophageal sphincter trachea upper esophageal sphincter uvula 16. The voluntary phase of swallowing is also known as the a. b. c. d. oral phase esophageal phase automatic phase oro-pharyngeal phase 17. During the swallowing process, the uvula contracts and nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 30 covers the opening of the nasopharynx, preventing food from entering a. b. c. d. the the the the lungs. trachea. larynx. nasal passages. 18. At the same time that the larynx moves upward to close the glottis, the __________ swings down and covers the opening of the larynx, acting like a cover. a. b. c. d. esophageal sphincter trachea epiglottis uvula 19. Once the food or liquid enters the esophagus it is moved along by the action of involuntary rhythmic muscles, which is called a. b. c. d. involuntary swallowing. peristalsis. pharyngeal reflex. esophageal reflex. 20. A person cannot inhale, exhale, talk, vomit, or cough when he or she is swallowing. a. True b. False 21. The gag reflex occurs when a foreign object touches the a. b. c. d. roof of the mouth or the back of the tongue. oropharynx. areas around the tonsils or the uvula. All of the above 22. Aspiration occurs when the gag reflex and the cough reflex nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 31 fail to prevent a foreign substance from entering a. b. c. d. the the the the nasal passages. uvula. lungs. glottis. 23. If the aspirate contains _________________ the patient may develop aspiration pneumonia. a. b. c. d. bolus fluids infectious bacteria saliva 24. Dysphagia is a medical term that means a. b. c. d. difficulty in swallowing. decreased level of consciousness. excessive production of oral secretions. prolonged vomiting. 25. A serious aspiration can only occur from a large volume or amount of a foreign substance entering the lungs. a. True b. False 26. Which of the following screening methods is a questionnaire, not a technical test for detecting aspiration or dysphagia? a. b. c. d. Barium swallow test EAT-10 Water swallow test Video-fluoroscopic evaluation (VSE) 27. Specific measures for preventing aspiration include: nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 32 a. b. c. d. use of sedative drugs to relax the patient. avoiding the use of antibacterial medications. eliminating liquids from diet. measuring residual gastric volume. 28. If a patient is receiving tube feedings and she or he is at risk for aspiration, tube feedings should be a. administered as a bolus. b. increased based on the CNA’s observations. c. given at the prescribed rate. d. given with sedative medication. 29. Typical signs or symptoms of aspiration include: a. b. c. d. persistent, mild cough. increased oxygen saturation. decreased sputum production. All of the above. 30. Which of the following questions is useful for performing a basic aspiration risk assessment? a. b. c. d. Is patient unable to sit upright? Is the patient elderly? Was general anesthesia recently used? All of the above. Correct Answers: 1. b 11. a 21. d 2. c 12. b 22. c 3. d 13. c 23. c 4. a 14. b 24. a 5. c 15. a 25. b nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 33 6. a 16. d 26. b 7. d 17. d 27. d 8. b 18. c 28. c 9. a 19. b 29. a 10. c 20. a 30. d References Section The reference section of in-text citations include published works intended as helpful material for further reading. Unpublished works and personal communications are not included in this section, although may appear within the study text. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Gastroenterology Nursing: A Core Curriculum Fifth Edition (2013). Society of Gastroenterology Nurses And Associates. AHRQ. 30 Safe Practices for Better Health Care. Accessed April 19, 2016 from. http://archive.ahrq.gov/research/findings/factsheets/errorssafety/30safe/30-safe-practices.html. Blaser AR, Starkopf J, Kirsimägi Ü, Deane AM. Definition, prevalence, and outcome of feeding intolerance in intensive care: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2014;58(8):914-22. Chen S, Xian W, Cheng S, et al. Risk of regurgitation and aspiration in patients infused with different volumes of enteral nutrition. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2015;24(2):212-218. Chen W, Cao Q, Li S, Li H, Zhang W. Impact of daily bathing with chlorhexidine gluconate on ventilator associated pneumonia in intensive care units: a meta-analysis. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7(4):746-753. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 34 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Elke G, Felbinger TW, Heyland DK. Gastric residual volume in critically ill patients: a dead marker or still alive? Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30(1):59-71. Eom CS, Jeon CY, Lim JW, Cho EG, Park SM, Lee KS. Use of acidsuppressive drugs and risk of pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2011;183(3):310-319. Khorvash F, Abbasi S, Meidani M, Dehdashti F, Ataei B. The comparison between proton pump inhibitors and sucralfate in incidence of ventilator associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Adv Biomed Res. 2014 Jan 27;3:52. doi: 10.4103/22779175.125789. eCollection 2014. Kuppinger DD, Rittler P, Hartl WH, Rüttinger D. Use of gastric residual volume to guide enteral nutrition in critically ill patients: a brief systematic review of clinical studies. Nutrition. 2013;29(9):1075-9. Li Bassi G, Torres A. Ventilator-associated pneumonia: role of positioning. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2011;17(1):57-63. McClave SA, Lukan JK, Stefater JA, Lowen CC, Looney SW, Matheson PJ. Poor validity of residual volumes as a marker for risk of aspiration in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2005;33(2):324-330. Metheny NA, Clouse RE, Chang YH, Stewart BJ, Oliver DA, Kollef MH. Tracheobronchial aspiration of gastric contents in critically ill tube-fed patients: frequency, outcomes, and risk factors. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(4):1007-1015. Noto MJ, Domenico HJ, Byrne DW, et al. Chlorhexidine bathing and health care-associated infections: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2015;313(4):369-378. Reignier J, Mercier E, Le Gouge A, http://www-ncbi-nlm-nihgov.online.uchc.edu/pubmed/?term=Boulain T%5BAuthor%5D&cauthor=true&cauthor_uid=23321763et al. Effect of not monitoring residual gastric volume on risk of ventilatorassociated pneumonia in adults receiving mechanical ventilation and early enteral feeding: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2013;309(3):249-56. Scolapio JS. Decreasing aspiration risk with enteral feeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2007;17(4):711-6. Shi Z, Xie H, Wang P, et al. Oral hygiene care for critically ill patients to prevent ventilator-associated pneumonia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013 Aug 13;8:CD008367. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008367.pub2. Review. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 35 The information presented in this course is intended solely for the use of healthcare professionals taking this course, for credit, from NurseCe4Less.com. The information is designed to assist healthcare professionals, including nurses, in addressing issues associated with healthcare. The information provided in this course is general in nature, and is not designed to address any specific situation. This publication in no way absolves facilities of their responsibility for the appropriate orientation of healthcare professionals. Hospitals or other organizations using this publication as a part of their own orientation processes should review the contents of this publication to ensure accuracy and compliance before using this publication. Hospitals and facilities that use this publication agree to defend and indemnify, and shall hold NurseCe4Less.com, including its parent(s), subsidiaries, affiliates, officers/directors, and employees from liability resulting from the use of this publication. The contents of this publication may not be reproduced without written permission from NurseCe4Less.com. nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com nursece4less.com 36