* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download The Ten Pillars of Buddhism

Pratītyasamutpāda wikipedia , lookup

Bhūmi (Buddhism) wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist art wikipedia , lookup

Early Buddhist schools wikipedia , lookup

Gautama Buddha wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist texts wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and violence wikipedia , lookup

Sanghyang Adi Buddha wikipedia , lookup

Buddha-nature wikipedia , lookup

History of Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Persecution of Buddhists wikipedia , lookup

History of Buddhism in Cambodia wikipedia , lookup

Decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent wikipedia , lookup

Silk Road transmission of Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

History of Buddhism in India wikipedia , lookup

Dhyāna in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Dalit Buddhist movement wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist cosmology of the Theravada school wikipedia , lookup

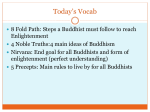

Noble Eightfold Path wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist philosophy wikipedia , lookup

Buddhist meditation wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Hinduism wikipedia , lookup

Pre-sectarian Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and psychology wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and sexual orientation wikipedia , lookup

Enlightenment in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Women in Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Greco-Buddhism wikipedia , lookup

Buddhism and Western philosophy wikipedia , lookup