* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Drugs of Abuse

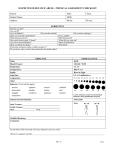

Survey

Document related concepts

Psychedelic therapy wikipedia , lookup

Compounding wikipedia , lookup

Orphan drug wikipedia , lookup

Drug design wikipedia , lookup

Neuropsychopharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Neuropharmacology wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacokinetics wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacogenomics wikipedia , lookup

Drug discovery wikipedia , lookup

Pharmaceutical industry wikipedia , lookup

Pharmacognosy wikipedia , lookup

Prescription costs wikipedia , lookup

Prescription drug prices in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Drug interaction wikipedia , lookup

Transcript