* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Appendix Review of Demand, Supply, Equilibrium Price, and Price

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

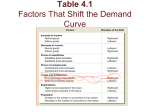

This Appendix has been written and supplied by Paul J. Feldstein. It represents a prepublication document that Professor Feldstein will include in his forthcoming Sixth edition of Health Care Economics. Philip J. Held, June 17, 2003. Appendix Review of Demand, Supply, Equilibrium Price, and Price Elasticity Assumptions Underlying Supply and Demand Analysis: Economics is concerned with being able to explain and predict observed outcomes. Innumerable factors affect observed outcomes, however, to make sense of which factors are, on average, most important, a theory is needed based on some simplified assumptions. The test of any theory is the accuracy of its predictions rather than the realism of its assumptions. A theory does not need to be perfect to be useful; it simply needs to be more accurate than alternative theories. The demand for goods and services starts with the simple assumption that consumers attempt to maximize their utility; that is, the satisfaction or benefits they derive from their choices. The consumer, however, has scarce resources; (s)he is subject to a budget constraint, consisting of their income, the 1 prices they must pay for different goods and services, and their own time. In making choices the consumer is assumed to be rational, that is, he or she attempts to evaluate the expected benefits and costs of their choices. And it is further assumed that consumers have information on the marginal benefits derived from their different choices and the marginal costs incurred for each of those choices, namely prices and time involved. Based on these assumptions, it is possible to predict the effect on the consumer’s choices when changes occur in the relative prices to be paid for different goods and services, in their time costs, and in their incomes. The supply side similarly assumes that the firm, the supplier of goods and services, has an objective, namely, to maximize their profits, subject to a budget constraint consisting of the prices they must pay for their inputs, labor and capital, and the price the firm receives for its output. The firm is also assumed to be knowledgeable regarding the most efficient method for producing its output (the most technically efficient production process), the prices it must pay for the various inputs used in the production process, and the price it receives for its output. Based on these assumptions it becomes possible to explain how firms choose the combination of inputs used in production and the amount of output they produce. 2 The above assumptions regarding consumer and producer behavior are not always fulfilled, particularly with respect to medical care; consumers have little knowledge of their illnesses and treatment needs and physicians, non-profit hospitals, and medical schools may have objectives other than maximizing their profits. When assumptions and objectives are different than hypothesized, it becomes possible to predict its consequences on consumer and producer behavior. The economic theory described below, when used at an aggregate level – not for individual consumers or particular physicians - is a powerful tool for explaining and predicting consumers and firms responses to changes in their budget constraints. Factors Affecting Demand Price: A change in the price of the service, such as a physician office visit, would result in a movement up or down the consumer’s demand curve for physician visits, all other factors affecting demand being held constant. As shown in Figure 1-3, a decrease in price from P1 to P2 would cause an increase in the quantity demanded of physician visits from Q1 to Q2. The demand curve pertains to a particular time period, such as quantity per month 3 or per year. The negative (inverse) relationship between price and quantity is referred to as The Law of Demand. There are two reasons for this inverse relationship. The downward sloping demand curve represents the declining marginal benefit to the consumer of purchasing additional units; the first unit offers the highest marginal benefit, the second, somewhat less, and so on. The quantity demanded by the consumer will depend on the price they must pay (which is the consumer’s marginal cost). When the price equals the marginal benefit they receive from consuming an additional unit, then the marginal cost to the consumer equals the marginal utility/benefit received from that last unit. If the price declines, the consumer would be willing to buy an additional unit whose marginal benefit is lower than the previous unit; at that point the marginal cost of the last unit again equals the marginal benefit of the last unit purchased. Along the demand curve the consumer is making a trade-off between the marginal benefit of consuming an additional unit versus the marginal cost (price) of buying that additional unit. The second reason for the downward sloping demand curve is that as the price falls, consumers who previously did not buy that item now enter the market. For the new consumers, the previously higher price exceeded the marginal benefit they would have gained from consuming that item (their marginal cost 4 exceeded their marginal benefit). As the price falls, the declining marginal cost equals their marginal benefit. Figure 1-3 About Here The downward sloping demand curve may be thought of as the consumer’s continual trade-off between their marginal benefit of buying additional units and the price (marginal cost) they must pay for each unit. Although the consumer would be willing to pay a high price for the first unit and a lower price for the next unit, and so on, when there is a single market price, the consumer only pays one price for all the units purchased. The difference between what the consumer is willing to pay for each unit and the amount they have to pay is called Consumer Surplus, graphically shown in Figure 1-4. At a price of $10 per unit the consumer would be willing to buy one unit; at a lower price of $9 the consumer would be willing to buy a second unit, and so on. The consumer would have been willing to spend $40 for 5 units ($10 + $9 + $8 + $7 + $6), which is the total value to the consumer of those five units. However, at a market price of $6, the consumer can buy 5 units for $30. The difference, $10, is consumer surplus. (As will be discussed in Chapter 10, The Physician Services 5 Market, a price discriminating monopolist attempts to price their service so as to capture the entire consumer surplus.) Figure 1-4 About Here Price of Substitute Products: A shift in the consumer’s demand curve for physician office visits will occur if there is a change in the price of a substitute to physician office visits (substitutes can partially replace the other service). A decrease in the price of chiropractic visits, a substitute to some extent for physician visits, will cause the demand curve for physician visits to shift to the left. As shown in Figure 1-5, with the price of physician visits unchanged, a decrease in the price of a substitute from P1 to P2, will cause the demand curve for physician visits to shift to the left, from D1 to D2, with a consequent decrease in demand for physician visits from Q1 to Q2. All other factors affecting the demand for physician services are assumed to be unchanged. The relationship between changes in the price of a substitute and physician visits is positive, meaning that as the price of the substitute decreases, so does the demand for physician visits, or an increase in the price of a substitute leads to an increase in demand for physician services. 6 Figure 1-5 About Here Price of Complementary Products: Complements are goods or services that are used together. Thus, an increase in the price of a complement will have a negative effect on the demand for physician visits; the demand for physician visits will shift to the left (right) if the price of a complement is increased (decreased). For example, as shown in Figure 1-6, a decrease in the price of diagnostic tests from P1 to P2 will not only increase the quantity demanded of diagnostic tests (a movement along its demand curve) but should result in an increase in the demand for physician visits to interpret those test results, from Q1 to Q2. When the price of a service increases and it leads to a decrease in demand for another service, then those two services are complements. When the price increase leads to an increase in demand for another service, then the two services are substitutes. Figure 1-6 About Here Income: 7 An increase in a family’s income relaxes their budget constraint and enables them to purchase more goods and services. Other factors affecting demand being held constant, an increase in income will cause the demand curve to shift to the right, resulting in an increase in demand for that service. See Figure 1-7. The positive relationship between income and demand is characteristic of a “normal” good. An “inferior” good is one where an increase in income results in a decrease in demand; a negative relationship. Medical care is considered to be a normal good, meaning as incomes rise, people prefer to spend a portion of their increased income on additional medical services. Tastes and preferences: There are a number of other, non-economic, factors, in addition to the economic factors described above that will cause the demand curve to shift, either to the right or left. Thus per capita use of medical services will differ even if different groups have the same incomes and face the same prices. These non-economic factors are usually included under the category of Tastes and Preferences. For example, an aging population will cause the demand for medical care to shift to the right; older males will have a greater demand for medical care (shift to the right) than older females. Differences in educational level and attitudes toward seeking care will cause shifts in the demand 8 for different medical services. Economists include both economic and non-economic factors affecting demand. (A more complete discussion of these non-economic factors is included in Chapter 5 “The Demand For Medical Care”.) Figure 1-7 About Here Population: Once all the economic and non-economic factors affecting demand have been specified, the size of the population becomes important. The more individuals there are in a community, the greater the demand for medical care; the demand curve shifts to the right, as shown in Figure 1-8. Not everyone has to be responsive to changes in price for a demand curve to have its negative slope. Even though some people will not change their consumption as prices change (their demand curve is vertical), others will. When all the individual demand curves are summed up, it is the marginal buyer, the ones that are responsive to price changes that result in an aggregate downward sloping demand curve. Figure 1-8 About Here Demand Equation: 9 A useful method for distinguishing between movements along a demand curve and shifts in demand, as well as the direction of those shifts is the following equation. The signs in front of each variable indicate the direction of the variable’s effect on demand. Qda = f( -Pricea, +Pricesub, -Pricecompl, +Income, +Tastes) x POP This equation states that the quantity demanded of a good or service is functionally related to (dependent upon) its Price; changes in price are a movement along the demand curve and the negative sign indicates that price is inversely related to quantity demanded. All of the remaining variables represent shifts in the demand for the service. An increase in the price of a substitute (positive sign) will cause the demand for A to increase, namely shift to the right. An increase in the price of a complement (negative sign) will cause the demand for A to decrease, shift left. An increase in income (positive sign), assuming it is a normal good, will cause the demand for A to shift right. Tastes represent non-economic factors that will cause shifts in the demand for A. The total demand for A is then equal to the sum of all the consumers’ demand in the market. 10 Factors Affecting Supply Price: The supply of a good or service is positively related to the price paid for that service. Higher product prices represent a movement along a supply curve. The producer is making a tradeoff between the marginal cost of producing an additional unit versus the marginal benefit (price) offered for that unit. As shown in Figure 1-9, the higher the price, from P1 to P2, the greater the willingness of the supplier to increase output; the firm can hire more employees and buy additional supplies to increase production. Along a given supply curve, the prices of labor and non-labor inputs are assumed to be unchanged. (The firm’s supply curve in the short run is it’s marginal cost curve (MC). Marginal cost is equal to the input price, e.g., the wage rate, divided by the input’s marginal productivity (MP). For example, assuming the wage rate is $10 and MP is 5 units, then MC equals $2 per unit. The reason the firm’s supply curve is upward sloping is because of the Law of Diminishing Returns. In the short run, meaning that time period in which there is some fixed input that cannot be expanded, such as the size of the building, as more labor is hired then, at some point, continually adding labor to work in that facility will result in a decrease in labor’s productivity. As the MP of 11 an additional employee declines, and is lower than the previous employee hired, marginal cost increases. Thus MC = W/MP = $10/5 = $2 per unit, with another employee MC = $10/4 = $2.50 per unit.) The firm will produce to the point where its marginal cost equals the price received for each unit of output. When the firm is producing at the point where its marginal costs equal its marginal revenue (the additional revenue received for each unit sold – which in this example is the price of the product), then the firm is maximizing its profits. The only way the firm can increase its output as its marginal costs increase is to be paid a higher price for its output. It is important to note that included in marginal cost are all the relevant costs to the firm, including opportunity costs, which are the sum of explicit (dollar) and implicit (value of the resource in its best alternative use, e.g., the highest wage the owner could have earned elsewhere) costs. Thus economic costs are different from accounting costs, which only include explicit costs. Figure 1-9 About Here Input Prices: The firm’s supply curve will shift because of a change in the price of either labor or non-labor inputs. An increase in the 12 wage rate will shift the supply curve upward (left), from S1 to S2. With the price of the product remaining unchanged at P1, an increase in the wage rate will decrease supply from Q1 to Q2, as shown in Figure 1-10. An example illustrates the shift left in supply as the wage increases. Assume that P2 in Figure 1-10 is $2 per unit and assume that MC = W/MP = $10/5 = $2 per unit. With both price and MC equal to $2 per unit, the firm will produce Q2 units. If the wage rate increases from $10 to $20, then MC = $20/5 = $4 per unit. The supply curve has shifted up; to produce the same rate of output, Q2, the price of the product would have to increase to $4 per unit. At a price of $4 per unit, the firm would have been able to produce a greater output with the previous supply curve, Q1. Figure 1-10 About Here Technology: Figure 1-10 can also be used to illustrate another reason for a shift in supply. Technological improvements that increase labor’s productivity increase each employee’s marginal product, thereby shifting the supply curve to the right or down, from S2 to S1. Again, assuming MC = W/MP = $10/5 $2 per unit, introducing a new technology that increases productivity would result in a decrease in marginal cost per unit; MC = $10/10 = $1 per unit. 13 Thus the same output, Q2, can be produced for less (on the new supply curve S1), or a greater rate of output, Q1 (on supply curve S1), could be produced for the same price. The following equation describes the factors affecting supply and the direction of each factor’s effect. The price at which the output is sold is positively related to the quantity supplied; changes in price represent a movement along a given supply curve. Changes in the price of labor and non-labor inputs cause the supply curve to shift; input price changes are inversely related to supply, an increase in input prices cause a decrease in supply, the supply curve shifts left. Technology that increases input productivity is positively related to supply, the supply curve shifts right. In addition to the price at which the product may be sold, the price of inputs and technology, there may be other supply factors that are relevant to a particular industry, such as weather affecting the supply of agricultural products. However, the determinants of supply described above, price, input prices, and technology, affect all industry supply curves. Number of Suppliers: In addition to these factors, the total supply of a product or service depends on the number of suppliers. Thus (similar to an increase in population on the demand side) an increase in the 14 number of suppliers will cause the supply curve to shift to the right; each supplier’s supply curve (their marginal cost curve) is summed horizontally to equal the industry supply curve for that product. Supply Equation: The following equation summarizes those factors affecting the supply of a product common to all industry supply curves. The quantity supplied is positively related to the price paid for the product; the supply curve will shift left (decrease) with an increase in the price of inputs; and supply will shift to the right (increase) with technological improvements that increase input productivity. An increase in the number of suppliers will also shift the supply curve to the right. Qsa = f( +Pricea, -Priceinputs, +Technology) x POP Market Equilibrium The interaction of supply and demand curves result in market equilibrium; a situation where, at the prevailing price, the quantity demanded equals the quantity supplied. The equilibrium price will not change unless there are changes in demand or 15 supply. Equilibrium is assumed to occur instantaneously, even though in reality neither demanders nor suppliers have perfect information when prices change. Market forces cause price to move toward equilibrium. Assume that the initial supply and demand curves are D1 and S1 in Figure 1-11A. The initial equilibrium price is P1 and output is Q1. Further assume that consumer incomes increase and that the service is a normal good. With an increase in incomes, demand shifts to D2. If equilibrium occurred immediately, price would rise to P2 and output would increase to Q2. (Note, the shift in demand results in a movement along the supply curve.) If consumers do not have perfect information, then with a shift in demand, consumers would demand Q3 output at the original price P1. Since the consumers would not be able to buy that amount of output at price P1, they would start to bid up the price. As the market price increases, suppliers are willing to increase the quantity supplied (a movement along their supply curve) and consumers realizing they have to pay a higher price move up their new demand curve, D2. When the price reaches P2, the market is again in equilibrium. Figure 1-11 About Here 16 Market Disequilibrium: Regulation When the government regulates the price of the product and does not permit the price to rise as demand increases, a shortage will develop. At price P1 and demand curve D2 in Figure 1-11A, demand exceeds supply and there is a shortage equal to Q3 – Q1. Shortages are resolved in one of several ways. Suppliers might ration the available supply, OQ1, according to who is willing to wait to receive the service; criteria, other than waiting times, might be used, such as favoritism, race, religion, etc. In health care markets examples of non-price rationing are admissions to medical schools and access to medical services when Medicare pays physicians fees that are lower than the market price. The Canadian health care system also uses waiting times as a rationing mechanism. Alternatively, a black market might develop in which consumers are willing to pay suppliers an amount that is greater than the regulated price. Physicians in regulated Eastern European health care systems have used this approach. (The marginal value to consumers of output Q1 is P3, which is the height of the demand curve at that point. Consumers would be willing to pay P3 but are unable to do so, consequently there will be a shift to the right in the demand for substitutes.) Figure 1-11B illustrates market equilibrium when there is a shift in supply. Supply will shift up or to the left with an 17 increase in the wage rate. (The shift in supply is a movement along the demand curve.) The higher price will result in a decrease in the quantity demanded of the product, from Q1 to Q2. If, however, prices are regulated and not permitted to increase as input costs rise, there will be a shortage, Q3 – Q1, similar to the earlier example. An example of input costs rising faster than regulated prices are rent controls on housing. Consequently, the quality of rent-controlled housing has deteriorated, leading to the abandonment of large numbers of rent-controlled buildings. (One might consider what hospitals’ response would be if Medicare payments to hospitals rose less rapidly than hospital input costs.) Market Equilibrium in Multiple Markets A shift in supply (or demand) in one market will not only affect market equilibrium in that market but will also cause changes in equilibrium prices and quantities in markets whose products are substitutes and complements. As shown in Figure 1-12, wage increases in the market for hospital care lead to a shift to the left in the supply of hospital services from S1 to S2. Hospital prices increase from P1 to P2 and there is a decrease in the quantity demanded of hospital care from Q1 to Q2. Outpatient surgery centers are a substitute for certain inpatient 18 surgeries. Thus the higher price for hospital care leads to a shift to the right in the demand for outpatient surgery centers (which is a movement along the supply curve for outpatient surgery). Similarly, higher hospital prices will lead to a shift to the left in the demand for complements to hospital care. Thus a change in any of the factors affecting demand or supply in one market will also lead to new equilibriums in markets that provide substitute and complementary services to the initial market experiencing a change in price. Figure 1-12 About Here Elasticity When there are price movements along the demand and supply curves as well as shifts in demand and supply, it is important for forecasting and public policy initiatives to have an estimate of the magnitude of those changes. Economists use the concept of elasticity, which standardizes the units of measurement, to indicate the quantitative impact of the factors affecting demand and supply. Price Elasticity of Demand: 19 The definition of the price elasticity of demand is the “percent change in quantity demanded divided by the percent change in price”. Price elasticity of demand is negative because of the inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. The formula for price elasticity is: DQ/Q %DQ = = -Pe DP/P %DP (Change is denoted by the symbol D and percent change by %D). For example, if price is decreased by 10 percent and quantity demanded increases by 20 percent, then the Pe equals -2. + 20% = -2. - 10% Similarly, if the quantity demanded changes by only 5 % with a 10 percent decrease in price, then Pe equals -.5 When the percent change in quantity demanded is greater (less) than the percent change in price, then the demand curve (at that point) is “price elastic” (“price inelastic”). Unit price elasticity is when the percent changes in price and quantity demanded are equal. 20 The better (or closer) the substitutes to a product, the greater the price elasticity of demand. How the product is defined, either broadly or narrowly, will determine the closeness of substitutes. The aggregate demand for hospital care in an area is typically price inelastic, since there are no close substitutes to hospital care. However, the demand for a particular hospital in a market with several hospitals is typically price elastic, since the other hospitals are substitutes to that hospital. The same occurs for all anesthesia services (price inelastic) in a market versus a single anesthesiologist (price elastic). Applications of Price Elasticity: The concept of price elasticity is useful for understanding pricing strategies, anti-competitive behavior and anti-trust, and public policies, such as national health insurance. A hospital that raises its price when it has a price elastic demand curve (close substitutes) will suffer a loss in total revenue, since the percent change in quantity demanded will exceed the percent increase in price. For example, if a hospital raises its price to a health insurer and nearby hospitals are considered to be very good substitutes, the health insurer is likely to shift more of its enrollees to those hospitals not raising their prices. With good substitutes, the 21 hospital raising its price will have a high price elasticity of demand and suffer a greater than proportionate decrease in the quantity demanded of its services; it’s total revenue will decrease. Conversely, if the hospital is the only one in the area, and the closest substitute is 100 miles away, then the hospital is likely to have a price inelastic demand curve; increasing its price will result in an increase in its total revenue. If all the anesthesiologists in a market formed one group, their demand curve would be price inelastic because there are no close substitutes to all anesthesiologists; increasing their prices would increase their total revenue. Eliminating competition by becoming a single firm monopolizes the market for anesthesia services. This type of behavior is anti-competitive. If the government subsidized the price of medical services to the uninsured, the cost of the program will be determined by whether the demand for medical services is price elastic or inelastic. Total expenditures (consequently the taxes required to finance the program) will be much higher if demand were price elastic than if it were price inelastic. (Assuming a price elasticity of –4.0, and the price is reduced from $100 to $50, quantity demanded would increase from 1,000 to 3,000 visits; the total cost of the subsidy will be $50 x 3,000 = $150,000. If instead the price elasticity were -.5, a 50 percent reduction in 22 price would lead to an increase in quantity demanded of only 250 visits; the total subsidy cost would then be $50 x 1,250 = $62,500. Cross Price Elasticity The concept of elasticity is also used to indicate the closeness of substitutes and the effect on complementary services of a change in price. For example, if the price of physician office visits increased, not only would there be a movement down the demand curve for physician visits, but there would be an increase (a shift to the right) in the demand for substitutes, such as chiropractic services. (See Figure 1-5.) Patient perceptions of how good a substitute chiropractic services are to physician services would determine how large a shift occurs in the demand for chiropractic services. The formula for cross price elasticity is the percent change in the demand for a substitute (chiropractic services) divided by the percent change in price of physician services. If the price of physician office visits increased by 10 percent the demand for chiropractic services might increase by 2 percent, resulting in an estimate of +.2. % DQchiro + 2% = +. 2 = % DPmd + 10% 23 If the price of physician office visits increased by 10 percent there would also be a decrease in demand (shift to the left) for complementary services, such as lab tests. (See Figure 1-6.) Thus if the demand for lab tests decreased by 5 percent then the cross price elasticity would be -.5. - 5% %DQlab tests = = -.5 %DPmd + 10% Price elasticity and cross price elasticity estimates are important for determining whether adding a new service as part of an insurer’s benefits will increase or decrease the total cost of that insurance. For example, if a health insurer includes a lower priced substitute, such as home health care, to an expensive service, such as hospital care, there will be an increase in the quantity demanded of that new service and a shift to the left in the demand for hospital care. Depending on the price elasticity of demand for the new service and the cross price elasticity of demand for hospital care, together with their respective prices, it can be determined whether the decrease in cost of hospital care more than offsets the increased cost of the new service. (For an illustrative calculation of including lower priced substitutes to decrease 24 the use of more expensive facilities see Chapter 6, Appendix 3: “The Effect on the Insurance Premium of Extending Coverage to Include Additional Benefits”.) Income Elasticity of Demand Income elasticity of demand is the percent change in demand for a given percent change in income. (See Figure 1-5.) If income elasticity is positive (a normal good) and the income elasticity is 1.5 then a 10 percent increase in income will increase (shift to the right) demand by 15 percent. %DQMd visits + 15% = +1.5 %DIncome + 10% Supply Elasticity The responsiveness of supply to changes in price of the service is given by the elasticity of supply. As price increases, so does the quantity supplied; a movement along the supply curve. If a 10 percent increase in price leads to a 20 percent increase in the quantity supplied, then the elasticity of supply is +2.0. %DQMd visits + 15% = +2.0 %DPMD visits + 10% 25 Competitive Industry Analysis Competitive markets serve as the basis for evaluating other types of markets, for understanding the reasons for the existence of price differences, and for predicting the consequences of changes in demand and supply. Although the assumptions of competitive markets, such as a homogeneous product, many buyers and sellers, and free entry and exit, are rarely fulfilled in the real world, the competitive model provides a basis for predicting the effect on prices and output if a particular assumption were violated. Further, as long as there are no entry barriers, competitive markets are a useful predictive tool. In the long run, after entry and exit from the industry has occurred and a new equilibrium is established, competitive prices will reflect the costs of production, including explicit as well as implicit costs. When prices equal their production costs, then the output of the industry is considered to be optimal, since the marginal benefits to consumers of those last units equal the marginal costs of producing those units. In other, less competitive, market structures price exceeds marginal cost; the greater the price over marginal cost, the lower the output, hence the greater the divergence from a competitive market. 26 When markets are reasonably competitive, then competitive models provide an explanation for observed differences in prices between regions (and within the same region over time). In the long run, differences in prices are the result of differences in cost, otherwise firms would enter the industry to compete away excess profits (prices greater than costs). Competitive models make it possible to predict the effects on prices and output (and prices and output of related industries) of changes in any of the factors affecting demand or supply of that product. Also, the consequences of regulated prices or barriers to entry can be predicted and evaluated using competitive market models. Further, hospital mergers can be evaluated for anti-trust purposes based upon whether the merger lessens competition in a market. (For a more complete discussion and review of competitive markets, see Chapter 7, “The Supply of Medical Care.”) Monopoly Analysis Monopoly analysis emphasizes pricing behavior according to the price elasticity of firm demand curves. When differences in prices cannot be explained by differences in costs (the competitive model explanation), then an economist seeks to explain those price differences by determining whether there are 27 differences in the price elasticity of demand, which is the monopoly explanation. Firms that have less price elastic demand curves will be able to charge higher prices than firms that have more price elastic demand curves, regardless of their costs. Firms that are able to segregate their purchasers according to their price elasticity of demand will be able to further increase their profits by charging higher prices to those with less price elastic demands for the service. Price discrimination has been and continues to be important to suppliers of health care services, such as physicians, hospitals, and pharmaceutical companies. The political position taken by health associations regarding government payment for their member’s services is often based on maintaining the ability to price discriminate. (Monopoly pricing is reviewed more completely in Chapter 10, “The Physician Services Market.”) Understanding Political Behavior By Using Supply and Demand Analysis Political positions of health interest groups can be understood using an economic framework. Health care firms compete in two markets, economic markets and political markets. Although firms, such as hospitals, compete against each other for patients and 28 for insurance contracts, these same firms are allies when it comes to regulations and legislation affecting hospitals. The same is true for all health interest groups and trade associations. Politically, health associations seek legislation to increase their member’s incomes. The types of legislation (or regulation) demanded by each health association are: to increase the demand for their member’s services, subsidies to lower their costs, increase the cost of their competitor’s services, and to erect entry barriers. (A more complete discussion of these types of legislation together with examples from different health associations is in Chapter 17, “The Legislative Marketplace”.) The economic motivation behind health associations’ legislative proposals can be illustrated using supply and demand analysis. Every health association wants the demand for their member’s services increased. For example, there would be an increase in the quantity demanded of physician services if a greater number of people had private insurance coverage for physician services. With insurance, the out-of-pocket price of physician services would be reduced, resulting in a movement down the demand curve for physician services (see Figure 1-3). The quantity demanded of physician services would increase. (Insurance pays the difference between the out-of-pocket price and the provider’s fees, thus in aggregate an increase in 29 insurance represents a shift to the right in the demand curve, see the Appendix to Chapter 5 on “The Effect of Co-insurance on the Demand for Medical Care.”) Thus all health associations favor continuation of the tax-exempt status for employer paid health insurance, which is a subsidy for the purchase of health insurance, and oppose any legislative attempts to reduce or limit the size of this tax exemption. Similarly all health associations favor mandated employer coverage, which would require employers to provide their employees with health insurance, thereby increasing the number of persons with private health insurance. Regulations that increase the costs, consequently prices, of substitutes are an effective demand increasing strategy; often these cost-increasing legislative proposals are in the guise of increasing quality of care. For example, physician associations have opposed legislation permitting Medicare and Medicaid to cover substitute services, such as chiropractors. Including chiropractors under public insurance programs would decrease the out-of-pocket price of chiropractic services for publicly insured patients, thereby causing a movement down the demand curve for chiropractic services and a shift to the left in the demand for physician services (see Figure 1-5). Similarly, for-profit health insurers favored legislation that would increase the costs of their non-profit substitute, Blue 30 Cross. Removing Blue Cross’ federal tax exemption would cause Blue Cross to increase its price, thereby shifting for-profit insurers’ demand curves to the right. An association would experience an increase in demand for their services (their demand curve would shift to the right) if the price of complementary services were decreased. For example, physicians favor including diagnostic and imaging services as an insured benefit. Health associations favor several supply-side legislative policies. Legislative subsidies that reduce the cost of inputs to the services provided by an association’s members, would shift their members’ supply curve down (or to the right). For example, medical associations favor legislation that would limit increases in physicians’ malpractice premiums. Similarly, hospital associations favor subsidies to increase the supply of registered nurses. The price of hospital care would be reduced, resulting in an increase in the quantity demanded of hospital care. Perhaps the most important legislative supply side policy favored by associations is preventing entry by new competitors. Referring to Figure 1-11A, an increase in demand along a given supply curve results in higher prices. Existing suppliers benefit from these higher prices and incomes. Over time, however, other suppliers will be attracted to this market. As 31 new suppliers enter the market, the supply curve will shift to the right (a movement down the new demand curve) and prices will decline. If existing suppliers are able to limit entry of new suppliers, the supply curve will not shift to the right and prices will remain higher than they would have been with free entry. Maintaining higher prices and incomes are a strong financial incentive for suppliers to seek legislation imposing entry barriers (usually justified on the basis of maintaining quality of care). Examples of entry barriers in health care are numerous. Medical associations have long favored limits on medical school capacity to restrict the number of new physicians. Hospitals and even home health agencies have favored Certificate of Need legislation that makes it difficult for new competitors to enter their market. The American Nurses Association favors immigration limits on foreign trained RNs, otherwise an increased supply of RNs would result in a decrease in RN wages. All professional health associations favor increased educational requirements before a health professional can practice; these requirements increase the cost of entering the profession, thereby reducing supply and, consequently, increasing prices and incomes for existing practitioners. Process measures for increasing quality are favored by every health profession instead of using outcome or testing procedures, which can be accomplished in a shorter 32 training time. When standards are increased for new entrants, currently practicing professionals are always exempt from the new, more rigorous, standards. 33 Price Price $10 $9 P1 $8 $7 P2 $6 D D Q1 Q2 1 Q/T Quantity 2 3 4 5 Q/T Quantity Figure 1-3 A Downward Sloping Demand Curve Figure 1-4 Consumer Surplus Price Price P1 P2 P1 D1 D D2 Q2 Q1 Physician Office Visits Q/T Q1 Q2 Chiropractic Services Figure 1-5 The Effect on the Demand for Physician Office Visits of a Decrease in the Price of a Substitute Q/T Price Price P1 P2 P1 D2 D D1 Q1 Q2 Q/T Q1 Physician Office Visits Q2 Chiropractic Services Figure 1-6 The Effect on Demand for Physician Office Visits of a Decrease in the Price of a Complement Price P1 D2 D1 Q1 Q2 Q/T Figure 1-7 The Effect on Demand of an Increase in Income Q/T Price P2 P1 D dA 0 Q1 dB dD dC Q2 Q3 Q4 Q5 Q6 Q8 Q7 Q/T Figure 1-8 Summing Individual Demand Curves to Obtain Market Demand Price Price S P2 S2 S1 P1 P1 P2 Q1 Q2 Q/T Figure 1-9 A Movement Along a Supply Curve Q2 Q1 Q/T Figure 1-10 A Shift in Supply Price Price S P3 S2 S1 P2 P1 P2 P1 D2 D D1 Q2 Q1 Q3 Q3 Q/T A: Demand Shift Q2 Q1 Q/T B: Supply Shift Figure 1-11 Market Equilibrium Price Price Price P1 P1 S2 S1 P2 P1 D2 D Q2 Q1 D1 Q/T Hospital Care D1 Q1 Q2 Outpatient Surgery Q/T D2 Q2 Q1 Diagnostic Tests Figure 1-12 Market Equilibrium in Multiple Markets Q/T