* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Document

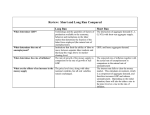

Survey

Document related concepts

Transcript

Production, Income, and Employment Slides by: John & Pamela Hall ECONOMICS: Principles and Applications 3e HALL & LIEBERMAN © 2005 Thomson Business and Professional Publishing Production and Gross Domestic Product, GDP: A Definition • U.S. government has been measuring nation’s total production since 1930s • Many conceptual traps and pitfalls – This is why economists have come up with a very precise definition of GDP – The nation’s gross domestic product (GDP) • Total value of all final goods and services produced for the marketplace during a given period within the nation’s borders 2 Production and Gross Domestic Product, GDP: A Definition • The total value – Approach of GDP is to add up dollar value of every good or service—the number of dollars each product is sold for • However, using the dollar prices at which goods and services actually sell also creates a problem – If prices rise, then GDP will rise, even if we are not actually producing more – GDP must be adjusted to take away the effects of inflation • …of all final… – When measuring production, we do not count every good or service produced in the economy • Only those that are sold to their final users • Avoids over-counting intermediate products when measuring GDP – Value of all intermediate products is automatically included in value of final products they are used to create 3 Production and Gross Domestic Product, GDP: A Definition • …goods and services… – We all know a good when we see one – Final services count in GDP in the same way as final goods • …produced… – In order to contribute to GDP, something must be produced • During the period being considered 4 Figure 1: Stages of Production 5 Production and Gross Domestic Product, GDP: A Definition • …for the marketplace… – GDP does not include all final goods and services produced in the economy • Includes only the ones produced for the marketplace—that is, with the intention of being sold • …during a given period… – GDP measures production during some specific period of time • Only goods produced during that period are counted • GDP is actually measured for each quarter, and then reported as an annual rate for the quarter • Once fourth quarter figures are in, government also reports official GDP figure for entire year 6 Production and Gross Domestic Product, GDP: A Definition • …within the nation’s borders – GDP measures output produced within U.S. borders • Regardless of whether it was produced by Americans – Americans abroad are not counted – However, foreigners producing goods or services within the country are 7 The Expenditure Approach to GDP • The Commerce Department’s Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) – Agency responsible for gathering, reporting, and analyzing movements in the nation’s output – Calculates GDP in several different ways • Expenditure approach divides output into four categories according to which group in the economy purchases it as final users – Consumption goods and services (C)—purchased by households – Private investment goods and services (I)—purchased by businesses – Government goods and services (G)—purchased by government agencies – Net exports (NX)—purchased by foreigners 8 The Expenditure Approach to GDP • Everyone who purchases a good or service included in U.S. GDP must be either a – U.S. household – U.S. business or – U.S. government agency (including state and local government) – Or else is part of the foreign sector • When we add up the purchases of all four groups we get GDP • GDP = C + I + G + NX 9 Consumption Spending • Consumption is the part of GDP purchased by households as final users – Almost everything households buy during the year is included as part of consumption spending when we calculate GDP – One exception is construction of new homes • Counted as private investment – Some quirky exceptions to the definition of consumption • Total value of all food products that farm families produce and consume themselves • Total value of the housing services provided by owner-occupied homes 10 Private Investment • Private investment has three components – Business Purchases of Plant, Equipment, and Software • A firm’s plant, equipment, and software are intended to last for many years— only a small part of them is used up to make the current year’s output • Are regarded and software as final goods, and firms that buy them as final users of those goods – New Home Construction • Residential housing is an important part of nation’s capital stock • House will continue to provide services into the future – Changes in Inventories • We count the charge in firms’ inventories as part of investment in measuring GDP • Why? – When goods are produced but not sold during the year, they end up in some firm’s inventory stocks – Part of the nation’s capital stock – Will provide services in the future, when they are finally sold and used 11 Private Investment and the Capital Stock: Some Provisos • Changes in the nation’s capital stock are somewhat more complicated than we are able to capture with private investment alone • Specifically, private investment does not include – Government Investment • An important part of the nation’s capital stock is owned and operated not by business, but by government—federal, state, and local – Consumer durables • Goods such as furniture, automobiles, washing machines, and personal computers for home use can be considered capital goods – Will continue to provide services for many years – Human capital • To measure the increase in capital stock most broadly we include the additional skills and training acquired by workforce during the year • In addition to excluding some types of capital formation, private investment also errs in the other direction – Ignores depreciation—the capital that is used up during the year 12 Government Purchases • Purchases by state, local governments and federal government are included • Government purchases include – Goods • Fighter jets, police cars, school buildings, spy satellites, etc. – Services • Such as those performed by police, legislators, and military personnel • Government is considered to be a purchaser even if it actually produces the goods or services itself 13 Government Purchases • Important to distinguish between – Government purchases • Which are counted in GDP – Government outlays • As measured by local, state, and federal budgets and reported in the media • Transfer payments represent money redistributed from one group of citizens (taxpayers) to another (poor, unemployed, elderly) – While transfers are included in government budgets as outlays they are not purchases of currently produced goods and services • Not included in government purchases or in GDP 14 Net Exports • Once we recognize dealings with the rest of the world, we must correct an inaccuracy in our measure of GDP – Deduct all U.S. imports during the year, leaving us with just output produced in United States • To properly account for output sold to, and bought from, foreigners – Must include net exports—difference between exports and imports—as part of expenditure in GDP 15 Other Approaches to GDP: The Value-Added Approach • Value added – Firm’s contribution to a product or – Revenue it receives for its output • Minus cost of all the intermediate goods that it buys • GDP is sum of values added by all firms in economy 16 Other Approaches to GDP: The Factor Payments Approach • In any year, value added by a firm is equal to total factor payments made by that firm • GDP equals sum of all firms’ value added – Each firm’s value added is equal to its factor payments • Thus, GDP must equal total factor payments made by all firms in the economy • All of these factor payments are received by households in the form of wages and salaries, rent, interest or profit – GDP is measured by adding up all of the income—wages and salaries, rent, interest, and profit—earned by all households in the economy • Gives us an important insight into the macroeconomy – Total output of economy (GDP) is equal to total income earned in the economy 17 Measuring GDP: A Summary • Different ways to calculate GDP – Expenditure Approach • GDP = C + I + G + NX – Value-Added Approach • GDP = Sum of value added by all firms – Factor Payments Approach • GDP = Sum of factor payments made by all firms • GDP = Wages and Salaries + interest + rent + profit • GDP = Total household income 18 Real Versus Nominal GDP • Since GDP is measured in dollars, a serious problem exists when tracking change in output over time – Value of the dollar—its purchasing power—is changing • Usually need to adjust our measurements to reflect changes in the value of the dollar – Nominal—when a variable is measured over time with no adjustment for the dollar’s changing value – Real—when a variable is adjusted for the dollar’s changing value • Most government statistics are reported in both nominal and real terms – Economists focus almost exclusively on real variables 19 Real Versus Nominal GDP • The distinction between nominal and real values is crucial in macroeconomics • The public, the media, and sometimes even government officials have been confused by a failure to make this distinction – Since our economic well-being depends, in part, on the goods and services we can buy • It is important to translate nominal values—which are measured in current dollars—to real values— which are measured in purchasing power 20 How GDP Is Used • Government’s reports on GDP are used to steer the economy over both short-run and long-run – In short-run, to alert us to recessions and give us a chance to stabilize the economy – In long-run, to tell us whether our economy is growing fast enough to raise output per capita and our standard of living, and fast enough to generate sufficient jobs for a growing population • Many (but not all) economists believe that, if alerted in time – Government can design policies to help keep the economy on a more balanced course 21 Figure 2: Real GDP Growth Rate, 1960–2003 22 Problems With GDP • Quality changes – While BEA includes impact of quality changes for many goods and services (such as automobiles and computers) • Does not have the resources to estimate quality changes for millions of different goods and services • By ignoring these quality improvements, GDP probably understates true growth from year to year 23 The Underground Economy • Some production is hidden from government authorities – Either because it is illegal or • Drugs, prostitution, most gambling – Because those engaged in it are avoiding taxes • Production in these hidden markets cannot be measured accurately – BEA must estimate it » Many economists believe that BEA’s estimates are too low » As a result, GDP may understate total output 24 Non-Market Production • GDP does not include non-market production – Goods and services that are produced, but not sold in the marketplace • Whenever a non-market transaction becomes a market transaction GDP will rise – Even though total production has remained the same • Can exaggerate the growth in GDP over long periods of time • What do these problems tell us about value of GDP? – For certain purposes—especially interpreting long-run changes in GDP—we must exercise caution • GDP works much better as a guide to short-run performance of economy – Short-term changes in real GDP are fairly accurate reflections of the state of the economy – A significant quarter-to-quarter change in real GDP virtually always indicates a change in actual production; rather than a measurement problem • This is why policy makers, business people, and the media pay such close attention to GDP as a guide to the economy from quarter to quarter 25 Types of Unemployment • In United States, people are considered unemployed if they are not working and actively seeking a job – Unemployment can arise for a variety of reasons, each with its own policy implications – This is why economists have found it useful to classify unemployment into four different categories – – – – Frictional unemployment Seasonal unemployment Structural unemployment Cyclical unemployment » Each arises from a different cause and has different consequences 26 Frictional Unemployment • Short-term joblessness experienced by people who are between jobs or who are entering the labor market for first time or after an absence • Because frictional unemployment is, by definition, short-term, it causes little hardship to those affected by it • By spending time searching rather than jumping at the first opening that comes their way – People find jobs for which they are better suited and in which they will ultimately be more productive 27 Seasonal Unemployment • Joblessness related to changes in weather, tourist patterns, or other seasonal factors • Is rather benign – Short-term – Workers are often compensated in advance for unemployment they experience in off-season • To prevent any misunderstandings, government usually reports the seasonally-adjusted rate of unemployment – Rate that reflects only those changes beyond normal for the month 28 Structural Unemployment • Joblessness arising from mismatches between workers’ skills and employers’ requirements – Or between workers’ locations and employers’ locations • Generally a stubborn, long-term problem – Often lasting several years or more 29 Cyclical Unemployment • When the economy goes into a recession and total output falls, the unemployment rate rises • Since it arises from conditions in the overall economy, cyclical unemployment is a problem for macroeconomic policy • Macroeconomists say we have reached full employment when cyclical unemployment is reduced to zero – But the overall unemployment rate at full employment is greater than zero • Because there are still positive levels of frictional, seasonal, and structural unemployment • How do we tell how much of our unemployment is cyclical? – Many economists believe that today, normal amounts of frictional, seasonal, and structural unemployment account for an unemployment rate of between 4 and 4.5% in United States 30 Figure 3: U.S. Quarterly Unemployment Rate, 1960–2003 31 The Costs of Unemployment: Economic Costs • Chief economic cost of unemployment is the opportunity cost of lost output – Goods and services the jobless would produce if they were working – But do not produce because they cannot find work • The unemployed are often given government assistance – Costs are spread among citizens in general – However, when there is cyclical unemployment, nation produces less output • Some groups within society must consume less output • Potential output – Level of output economy could produce if operating at full employment 32 Figure 4: Actual And Potential Real GDP, 1960–2003 33 Broader Costs • Unemployment—especially when it lasts for many months or years – Can have serious psychological and physical effects – Also causes setbacks in achieving important social goals • Burden of unemployment is not shared equally among different groups in the population – Tends to fall most heavily on minorities, especially minority youth 34 How Unemployment is Measured • The unemployed are those willing and able to work, but who do not have jobs • Others were able to work, but preferred not to – Including millions of college students, homemakers, and retired people – Still others were in the military and are counted in the population • But not counted when calculating civilian employment statistics • To be counted as unemployed, you must have recently searched for work – But how can we tell who has, and who has not, recently searched for work? 35 The Census Bureau’s Household Survey • Every month, thousands of interviewers from United States Census Bureau—acting on behalf of the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS)—conduct a survey of 60,000 households across America – Household members who are under 16, in the military, or currently residing in an institution like a prison or hospital are excluded from survey • Official unemployment rate – Percentage of the labor force that is unemployed Unemployme nt rate Unemployed Unemployed Labor Force (Unemploye d Employed) 36 Figure 5: How BLS Measures Employment Status 37 Problems In Measuring Unemployment • Many economists believe that our official measure seriously underestimates extent of unemployment in our society due to – Treatment of involuntary part-time workers • Some economists have suggested that involuntary part-time workers should be regarded as partially employed and partially unemployed – Treatment of discouraged workers • Individuals who would like to work but, because they feel little hope of finding a job, have given up searching – How many discouraged workers are there? » No one knows for sure • Still, the unemployment rate—as currently measured— tells us something important – Number of people who are searching for jobs, but have not yet found them 38 Figure 6: Employment Status of the U.S. Population—June 2003 39 GDP After September 11 • On September 11, 2001, United States suffered an unprecedented terrorist attack • What would happen after September 11? – Would the recession deepen? • How badly? – Could the economy actually tilt into a depression? – What was the appropriate economic policy, and how should it be orchestrated? • Helpful to distinguish between – Direct impact of GDP • Direct result of destruction itself – Indirect impact • Resulting from choices of economic-decision makers in the weeks, months, and even years following the attack 40 The Direct Impact On GDP • At first, it seems that the direct impact of the attacks on GDP should be huge • GDP is not designed to measure the resources at our disposal, but rather the production we get from those resource – The destruction caused by the terrorist attacks of September 11 had almost no direct impact on the U.S. economy or U.S. GDP 41 Indirect Impacts on GDP: The Short Run • Indirect losses to GDP were significant • Useful to distinguish between – Short-run impact • Weeks and months following the attacks – long-run impact • We’ll be experiencing for several years • Did not take long for aftermath of attacks to affect economic decision making – Federal government immediately shut down airports nationwide for more than 48 hours • With fewer people flying, hotel occupancy rates also decreased—by about 20% • Problem spread to manufacturing and raw materials sectors of the economy 42 Indirect Impacts on GDP: The Short Run • Consumers made other decisions that affected production – Instances of increased production – But these increases in production were swamped by production cuts already rippling through the economy • GDP did a good job of capturing all of these changes in spending and production – Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that production turned southward in the third quarter of 2001 • With much of the decline occurring during the three weeks of the quarter that remained after September 11 43 The Long-Run • In the weeks following the attack, it became clear that U.S. was about to start on a course it would follow for many years – Huge reallocation of national resources toward fighting terrorism abroad and achieving greater security at home • Some of these resources are being purchased by the government • Over the next two years, U.S. spent billions of additional dollars pursuing a more aggressive foreign policy including – Invasion to overthrow regime of Saddam Hussein in Iraq – Increased aid to allies—and potential allies—in war against terrorism 44 The Long-Run • But private businesses have been spending more for security each year than they did before • All these security expenses are slowing growth of our potential output – Therefore slowing growth of real GDP over long-run – In long-run, as the nation shifts production away from other goods and services and toward security in the wake of September 11, impact on real GDP will be negative – Potential output—and over the long-run, actual output— will grow more slowly than it otherwise would have 45