* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download High Court decision could change election result

Survey

Document related concepts

R v Secretary of State for Foreign and Commonwealth Affairs, ex p Bancoult (No 2) wikipedia , lookup

Polish Constitutional Court crisis, 2015 wikipedia , lookup

R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional Court of Thailand wikipedia , lookup

United States presidential election, 1876 wikipedia , lookup

United States constitutional law wikipedia , lookup

Voting rights in the United States wikipedia , lookup

Coloured vote constitutional crisis wikipedia , lookup

Voting rights in Singapore wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

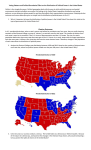

The High Court and Ordinary Law Establishing new common law precedents Old School Mabo (1992) Wik (1996) Shows creation of new precedent, judicial activism, law making relationship between courts and parliament and parliamentary sovereignty. Also look at the development of Native title law – Ward (2002) and Blue Mud Bay (2008) Then look at Dietrich (1992). Implied rights The High Court and the common law of negligence Over the past twenty years the High Court decisions have significantly altered the ways the common law of negligence is applied in Australia. Cases we are familiar with: Nagle v Rottnest Island Board (1993) Mulligan v Coffs Harbour City Council (2005) New and sexy Harrinton v Stephens Wrongful Life Case Law making Parties, pressure Groups, Joe Average and Law making. PG’s organized associations that attempt to influence public policy, either to change or maintain it. Joe Average Individuals can join parties and pressure groups, but they can also act alone to influence political policy. Australian politics provides many examples of the capacity of individuals to influence the legislative agenda. Individuals can also promote causes and become directly involved in the passage of laws as independent members of parliament. Individuals can also influence the development of common law, law developed through the courts. Courts deal with disputes between individuals. Bringing a case to court can act as a means of highlighting a legal issue, even as a way of predicating change in legal precedent. Individuals – Cases Roach Pressure Groups - Case Rowe See Lawmaking Handout Elections and Democracy Year 11 & Year 12 Participation and Democracy Minimum requirement of a democracy is free and fair elections. Democratic society is based on the ability of individuals and groups to influence decision makers. Elections make governments accountable to the people. How effective they are at this depends on the quality of political rights and the electoral system used. A fair voting system should: Maximize participation by all citizens Provide equal voting power – one vote, one person, one value Guarantee electoral rights Fair elections are a significant part of good governance. The first requirement of fair elections is that the government is accountable to all the people . There should be equal voting rights for virtually all adults. The exclusion to vote should only be limited to special cases such as the mentally insane. Currently there are some restrictions on those that can-not vote. An undemocratic restriction on electoral rights. Permanent Residents can-not vote Not all prisoners can vote. In 2006 The Coalition lead by John Howard legislated to remove the right to vote from all people serving time in prison. The legislation was challenged in the High Court. Roach 2007. The High Court ruled that the total prohibition of all prisoners being restricted from voting was unconstitutional. But stopped at saying the legislation as a whole was unconstitutional. Prisoners serving three or more years are still unable to vote. Roach ‘directly chosen by the people’ in ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution These words had been applied by the Gleeson Court in Roach v Electoral Commissioner to strike down a voting ban imposed by the same 2006 statute upon all prisoners serving a sentence of full-time detention. Rowe is an important decision in the ongoing development by the High Court of the words ‘directly chosen by the people’ in ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution. It establishes that the Constitution has implications for Australian electoral law beyond the question of who may or may not vote. The Constitution applies to a range of other matters, beginning with enrolment. Integrity of the Electoral Roll Central to the conduct of a free and fair election is the integrity of the electoral roll. The integrity of the electoral roll must not compromised and all Australians should have confidence in the accuracy of the roll. The seven day grace period between the issuing of the writs and the closure of the rolls which was abolished by the 2006 changes to the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 was effectively reinstated by the order of the High Court issued on 6 August 2010 finding this provision to be unconstitutional. The decision of the High Court in Rowe v Electoral Commissioner which appears to have constitutionally entrenched the seven day grace period between the issue of the writ and the closure of the rolls that was supported by statute law from 1984-2006, the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 The Constitution provides no express guarantee of a universal franchise. The qualification of electors was clearly left for the ultimate decision of the federal Parliament. This may have been because at the time of federation, the colonies had a number of different approaches to voting. Only South Australia and Western Australia recognised the right of women to vote; Aborigines and other racial minorities were explicitly excluded by the law of some colonies;3 those in receipt of government benefits could not vote in some colonies; and some colonies imposed a property, income or education requirement to determine who was eligible to vote. The most immediately relevant section of the Constitution is s 41, which is cast in the following terms: * No adult person who has or acquires a right to vote at elections for the more numerous Houses of the Parliament of a State shall, while the right continues, be prevented by any law of the Commonwealth from voting at elections for either House of the Parliament of the Commonwealth. Other sections also of relevance include s 24, requiring that the members of the House of Representatives be chosen directly by the people, and s 30, providing that until the (Commonwealth) Parliament otherwise provides, the qualification of electors of members of the House of Representatives shall be in each state that prescribed by the law of the state as the qualification for electors of the state Parliament. There seems little doubt that the reason for the inclusion of the s 41 was to protect the existing colonial franchises at the time of federation. Different colonies had different requirements. Only South Australia and Western Australia gave women the right to vote. Tasmania required voters to own a certain amount of property. Some colonies allowed plural voting; others did not. Aboriginal people were excluded from voting in most colonies; and in New South Wales anyone in receipt of state aid or aid from a charitable institution was not entitled to enrol.4 The founding fathers were concerned that the previous arrangements would not be disrupted by the creation of the new federal Parliament.5 Of course, there was a need to gain support for the new Constitution, so an attempt to minimise change to existing arrangements, where possible, was understandable. Roach v Electoral Commissioner The plaintiff was an Australian citizen of indigenous descent. She was convicted in 2004 of five offences under the Crimes Act 1958 (Vic) and sentenced to a total of six years effective imprisonment. She was of sound mind and had not committed treason or treachery. This was important because under the relevant provisions of the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 (Cth), prior to amendments in 2006, the following were excluded from the right to vote: (a) those who through unsound mind were incapable of understanding the nature and significance of enrolment and voting; (b) those serving a sentence of three years or more for an offence against the law of the Commonwealth or State; and (c) those convicted of treason or treachery. An amendment in 2006 to (b) above extended its reach to those serving any term of full-time imprisonment. This amendment had the effect of excluding Roach from voting. She challenged the constitutionality of the amendment, and in a 4-2 verdict, the High Court partly upheld her complaint. Majority Reasoning Gleeson CJ noted that the founding fathers had left it to Parliament to prescribe the form of our system of representative democracy. Interestingly, he noted that ‘Australia came to have universal adult suffrage as a result of legislative action’, before these comments: Could Parliament now legislate to remove universal suffrage? If the answer to that question is in the negative (as I believe it to be), then the reason must be in the terms of ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution, which require that the senators and members of the House of Representatives be ‘directly chosen by the people’ of the State or the Commonwealth respectively. In 1901, those words did not mandate universal suffrage8 … the words of ss 7 and 24, because of changed historical circumstances including legislative history, have come to be a constitutional protection of the right to vote. Because the franchise is critical to representative government, and lies at the centre of our concept of participation in the life of the community, and of citizenship, disenfranchisement of any group of adult citizens on a basis that does not constitute a substantial reason for exclusion from such participation would not be consistent with choice by the people. Gleeson CJ noted that not all people in prison were serving sentences of imprisonment – some 22 per cent were on remand. Many people were in prison for relatively short sentences – he referred to a New South Wales (NSW) report that found 65 per cent of NSW prisoners in the early years st of the 21 century had been sentenced to less than six months imprisonment. Many prisoners, due to poverty, homelessness or mental difficulties, did not qualify for non-custodial orders. Though acknowledging the different statutory frameworks and different scope for judicial review, he noted decisions of the Canadian Supreme Court and the European Court of Human Rights that arbitrary denial of the right to vote was invalid. While he would have accepted as valid the legislative provision denying the right to vote to prisoners serving a term of imprisonment of at least three years, he found the amending provisions here were arbitrary, breaking the rational connection necessary to reconcile the disenfranchisement with the constitutional imperative of choice by the people The joint reasons noted that: Voting in elections for the Parliament lies at the very heart of the system of government for which the Constitution provides. This central concept is reflected in the detailed provisions for the election of the Parliament of the Commonwealth in what is otherwise a comparatively brief constitutional text …McGinty does not deny the existence of a constitutional bedrock when what is at stake is legislative disqualification of some citizens from exercise of the franchise. The joint reasons explained that representative government embraced not only the bringing of concerns and grievances to the attention of legislators, but also the presence of a voice in the selection of legislators. In this way, the existence and exercise of the franchise reflected notions of citizenship and membership of the Australian federal body politic,that could not be extinguished by mere imprisonment. A prisoner retained an interest in, and duty to, their society and its governance. They found that the amendments were invalid, as they did not discriminate in terms of seriousness of offence, and were incompatible with past acceptable restrictions on the universal franchise. They went beyond what was reasonably appropriate and adapted to the maintenance of representative government. The expression in s 24 requiring Parliament to be chosen ‘directly by the people’ was an expression of generality, not universality. It did not mandate universal suffrage. Denying prisoners voting rights was consistent with the s 24 requirement, and even if universal suffrage were accepted, it allowed for exceptions. As the joint reasons had noted, Hayne J observed that prior to federation there was no consistency of voting rights among the colonies. GetUp! High Court win overturns Howard's electoral laws Dan Harrison and Tom Arup , August 6, 2010 The High Court has ruled that Howard-era laws that close the electoral rolls on the day that writs for an election are issued are invalid. The Australian Electoral Commission will now scramble to contact an estimated 100,000 Australians to inform them they are entitled to vote at the election on August 21. Activist group GetUp! brought the constitutional challenge, arguing the laws effectively disenfranchised young people who were prevented from registering when the rolls closed on July 19. About 1.4 million Australians - or about 6 per cent of the population - are not enrolled to vote, with 70 per cent aged between 18 and 39, the commission says. Before the 2006 changes, people had seven days to enrol to vote or update their details after writs for an election were issued. The amendment brought the cut-off for new enrolments forward to 8pm on the day writs are issued, and to three days later for those on the roll who need to update their details. The court did not publish reasons for its decision, saying a majority had declared the changes invalid. GetUp!'s national director Simon Sheikh called the decision "historic" and said it could make a difference in some marginal seats in the coming poll. He said that never before in Australia’s history had a case of this magnitude been won in a two-week period. The decision affects 100,000 people who enrolled after one day and within one week of writs being issued. GetUp! would not push for the AEC to reopen the electoral roll, Mr Sheikh said. About 20 lawyers, led by Ron Merkel, QC, worked around the clock on a pro-bono basis. The High Court has ordered their costs be covered by the Commonwealth. Success was not a given, but it now had the potential to make a significant impact come polling day, Mr Sheikh said. "Clearly 100,000 Australians who can now exercise their right to vote is an extraordinarily large number," Mr Sheikh said. "With marginal seats across the country and an extremely tight election, [this] could have a massive impact on the election." He accused the Howard government of "political manoeuvres" in amending the electoral laws in 2006. Mr Sheikh said the legal victory was the first step to getting all eligible voters on the electoral roll. The opposition’s accountability spokesman Michael Ronaldson defended the 2006 changes as moves to strengthen the integrity of the electoral roll. It was now open to rort and abuse, he said. But Special Minister of State Joe Ludwig welcomed the High Court’s decision, saying it restored democratic rights. High Court decision could change election result Lanai Vasek: The Australian, August 07, 2010 12:00AM Up to 100,000 disenfranchised Australians may now vote on August 21 THE High Court has restored the vote to up to 100,000 Australians, who will be added to the rolls in time for the August 21 election. On what was hailed as a "historic day" for democracy, the court handed down its majority ruling yesterday in the fastest-ever turnaround for a full bench hearing. Shannen Rowe and Douglas Thompson, members of political advocacy group GetUp!, challenged the constitutional validity of changes the Howard government made to the Electoral Act in 2006. Experts predicted the decision may have consequences for future constitutional challenges and could have an impact on the outcome of the election. Before the changes were made, voters had seven days after an election was called to enrol. Under current law, the rolls shut at 8pm on the day election writs are issued for all new enrolments and three days later for those who need to update their addresses. Chief Justice Robert French ruled yesterday the amendments being challenged were "invalid". The court did not publish reasons for its decision but it ordered the commonwealth to pay the plaintiffs' costs. The Electoral Commissioner was the defendant in the hearing, which stretched over two days. The Australian Electoral Commission and the commonwealth were supported by the Attorney-General for Western Australia. GetUp! national director Simon Sheikh said the ruling could have a significant impact on polling day. "Clearly 100,000 Australians who can now exercise their right to vote is an extraordinarily large number," Mr Sheikh said. "With marginal seats across the country and an extremely tight election, (this) could have a massive impact on the election." Yesterday's decision was expedited because of the election, after a request to the court by the Electoral Commission. Ms Rowe and Mr Thompson brought their challenge after they missed out on being correctly enrolled when writs were issued on July 19. About 20 lawyers, led by Ron Merkel QC, worked around the clock on the case on a pro-bono basis. Mr Thompson told The Weekend Australian yesterday he was proud to be part of a significant change to the Australian democratic landscape. "I think it's a great thing; it's much bigger than Shannen and I," the 23-year-old Sydney student said. AEC spokesman Phil Diak said voters affected by the decision would have to cast a declaration vote and provide an accepted form of evidence of identity on polling day. Wayne Errington, a lecturer in politics at Adelaide University, said he believed the Coalition would be the biggest loser from the court's ruling. "If most of those 100,000 are younger voters, well, it's certainly the likelihood that the Coalition would get very little of those votes," Mr Errington said. About 1.4 million Australians -- or about 6 per cent of the population -- are not enrolled to vote, with 70 per cent aged between 18 and 39. Patrick Keyzer, professor of constitutional law at Bond University, said the decision was "surprising" but believed it would have major future legal ramifications. "It's a significant development in electoral law, it advances the notion of a right to vote in constitutional law," Professor Keyzer said. "I think that any future parliament would be reading this case carefully before it disenfranchised voters in the future." Greens leader Bob Brown welcomed the decision, saying the amendments should never have been passed. Special Minister of State Joe Ludwig also welcomed the ruling. But Liberal senator Michael Ronaldson said he was concerned it would open the door for electoral fraud. In Rowe v Electoral Commissioner, the Court was able to get to the nub of the constitutional question. At issue were changes to the Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918 made by the Electoral and Referendum Amendment (Electoral Integrity and Other Measures) Act 2006 (Cth) that prevented the Electoral Commissioner from considering: (1) claims for enrolment lodged after 8pm on the date of issue of the writs for an election, and (2) claims for transfer from one divisional roll to another lodged after 8pm on the third working day after the date of issue of the writs. Before the amendments, people had been accorded seven days after the writ was issued before the electoral roll was closed. At the 2010 election, the Australian Electoral commission estimated that the new provisions would prevent some 100, 000 people from voting The provisions were challenged by two of the excluded voters, backed by the advocacy organisation GetUp!, who argued that the change breached the requirement in ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution that members of the Federal Parliament be ‘directly chosen by the people’. These words had been applied by the Gleeson Court in Roach v Electoral Commissioner to strike down a voting ban imposed by the same 2006 statute upon all prisoners serving a sentence of full-time detention. In Rowe, by 4:3 (French CJ, Gummow, Crennan and Bell JJ, with Hayne, Heydon and Kiefel JJ dissenting), these words were again applied to strike down the early closing of the electoral roll. According to French CJ: ‘An electoral law which denies enrolment and therefore the right to vote to any of the people who are qualified to be enrolled can only be justified if it serves the purpose of the constitutional mandate.’ This was determined by asking: ‘If the law’s adverse legal or practical effect upon the exercise of the entitlement to vote is disproportionate to its advancement of’ that mandate’. In Rowe, the majority held that the removal of the seven-day period, with the effect of disenfranchising some 100,000 people, could not be justified by any of the purposes underlying the change. In particular: there was nothing to support a proposition ... that the impugned provisions would avert an existing difficulty of electoral fraud. Nor was there anything to suggest that the [Australian Electoral Commission] had been unable to deal with late enrolments. Indeed, it had used the announcement of an election, coupled with the existence of the statutory grace period, to encourage electors to enrol or apply for transfer of enrolment in a context in which its exhortations were more likely to be attended to and taken seriously than at a time well out from an election. The main point of dissent was that the Commonwealth Electoral Act as amended provided adequate opportunities for electors to enrol, and indeed mandated that they do so in a timely fashion. The dissenters found that a lack of enrolment or updating of details spoke of a failure of personal responsibility rather than any constitutional problem. As Heydon J stated, the plaintiffs were the ‘authors of their own misfortunes’. He concluded that it was not possible to invalidate ‘an electoral system which works satisfactorily in relation to those who are not inefficient, apathetic, or conscientiously indisposed to participate. Rowe is an important decision in the ongoing development by the High Court of the words ‘directly chosen by the people’ in ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution. It establishes that the Constitution has implications for Australian electoral law beyond the question of who may or may not vote. The Constitution applies to a range of other matters, beginning with enrolment. The fact that any protected feature of the system may not have been part of federal electoral law in 1901 is beside the point. Rowe again demonstrates the interplay between statute law and the Constitution in this area, and how the evolution of the latter is driven in large part by standardsetting in the former (and not, as had been suggested in Attorney-General (Cth); Ex rel McKinlay v The Commonwealth by ‘the common understanding of the time’’). By this means, a statutory innovation can become an entrenched constitutional principle in the years to come. It is hard to see where the limits of this lie. As French CJ stated: ‘[A]ll laws of the Commonwealth Parliament providing for enrolment and for the conduct of elections must operate within the constitutional framework defined by the words ‘directly chosen by the people’.’ It is not such a big step to suggest that aspects of how ballots are cast, and in particular the secret ballot, may be constitutionally entrenched. It may also be that the constitutional expression ‘the people’ will be a source of further development. For example, does the constitutional protection of the right to vote of ‘the people’ negate restrictions imposed by the Commonwealth Electoral Act on the voting rights of Australian citizens living overseas? Court by surprise: the High Court upholds voting rights GetUp! has scored an unexpected victory in the High Court, giving an extra 100,000 people a chance to vote on 21 August and opening up the debate about the right to vote, writes Graeme Orr 06 August 2010 FOUR YEARS AGO, in controversial circumstances, the Howard government legislated to close the electoral roll significantly earlier once an election was called. After the election campaign formally began, new voters had only until 8pm on the day the electoral writ was issued to lodge their enrolment form. Those voters who needed to update their addresses were allowed a bare three days. Given that our quaint Westminster heritage gives prime ministers the right to call an election when it suits them, it was hardly a democratic measure. New Zealand electors, for instance, can enrol up until polling day. Canadians can enrol on polling day. Early roll closure did not even have the support of electoral bureaucrats. In the past, the Australian Electoral Commission, or AEC, has handled hundreds of thousands of roll changes in the first week of the campaign, and uncovered no systemic attempts at fraudulent enrolment. But an attempt by Labor to reverse the 2006 legislation was blocked by the Senate and this month’s election kicked off under the Howard-era rules. Barely a fortnight ago, the progressive lobby group Get Up! launched a challenge to this law. The case is named after the test-case plaintiff, Shannen Rowe. As if to show the other branches of government that leisurely approaches are inapt when fundamental rights are involved, the High Court rushed the case on for hearing. And within a day it brought down its verdict. The majority ruling in Rowe’s case has struck down early closing of the roll. Shrewdly, the head of Get Up!’s pro bono legal team, Ron Merkel QC, did not ask the Court to take a step into the unknown, so the Court has not ruled that enrolment cut-off days are entirely unnecessary, as in Canada. Nor has it ruled that in a 24/7 society paper-based enrolment is unreasonable. Instead the law has simply jackpotted back to the pre-Howard rule, dating back to 1983, that electors have seven days’ grace to organise their enrolment. The immediate effect is that approximately 100,000 enrolments will be processed that otherwise would have lain in abeyance. Some of these are not new enrolments: just a matter of getting people into their correct electorates. The figure could have been much higher: we will never know how many people were deterred from trying to enrol because they thought they were too late. The longer-term effects of the decision are hard to assess. The Court rushed down its orders, but will take some weeks to craft its reasons. It is not yet clear whether the majority was a clear or paper-thin one. Unless four judges agree not just on the outcome but also on the basis for it, the case may be confined to roll closure rather than influencing future disputes over voting rights. By judicial standards, the Court is full of relatively new members. As in some other key cases, one suspects a plurality opinion, if not a single majority opinion, will be crafted around the Court’s older, centrist judges, Justices Gummow and Hayne. Regardless, the outcome is surprising. The High Court can be hard to predict, but in recent years it has generally been conservative in methodology and outlook. Until four years ago, it was not even clear that the Constitution protected the universal franchise at all, let alone the machinery that gives it life. It took another piece of Howard government overreach – the disenfranchisement of all prisoners – to stir the sleeping giants on the bench. In a case involving an Indigenous prisoner, Vicky Roach, a majority finally agreed with old and long-gone Labor judges, such as Lionel Murphy and Edward McTiernan, that the rule that federal parliament be “chosen by the people” means that parliament may only limit the franchise in ways that are reasonable or proportionate to representative democracy. The result of Roach’s case was not radical. Only “short term” prisoners benefited from that ruling. But Roach’s case, along with the political broadcasting, or ACTV, case of 1992, gives the Court a backstop role. It has no place micro-managing electoral law, but it has reserved to itself a power of veto over unnecessary restrictions on voting rights or political communication. To what extent do such rulings empower the judicial branch over others? Discussion from the bench in Rowe’s case suggests that at least one judge is interested in the very American idea of applying “strict scrutiny” to legislation that affects fundamental political rights at least where parliament may be motivated by self-interest. None of this means the Court is boot-strapping a Bill of Rights, however, let alone turning itself into a vanguard of the civil-rights movement, like the Warren Court in the United States. The Australian judicial tradition of deferring to parliamentary expertise or discretion remains immanent in many other decisions. The majority opinions in Rowe’s case will probably be narrowly crafted. They will highlight the fact that early roll closure was not evidence-based legislation: the Howard government merely asserted a risk of fraud, without giving reasons or evidence to support itself. The opinions will also rely on the fact that Australia does not have fixed parliamentary terms. Some judges will point to compulsory enrolment and voting as a reason to ensure that enrolment procedures are not too burdensome. Contrarily, it is likely that judges in the minority will take the conservative view that compulsion should work the other way – that it is the individual’s responsibility to maintain their enrolment, and giving them thirty-five out of thirty-six months in an electoral cycle is plenty of time. Curiously, the Commonwealth did not argue the case by analogy with United States law. There, despite a much stronger judicial interest in voting rights, the Supreme Court has accepted registration cut-offs of between thirty and even fifty days. Perhaps the Commonwealth thought that appealing to American practice in electoral legislation would not smack of best practice. Perhaps their lawyers reasoned that the United States has fixed terms and primaries, so electors have year-round notice of when elections are due. Or perhaps in the hurried hearing, they simply overlooked comparative law. What does the case mean politically and institutionally? Julia Gillard rushed to an election, which she announced back on Saturday 19 July. She could have delayed the writs – and hence roll closure. Indeed for a long time that was the practice in Australia. Prime ministers of old would delay issuing the writs from anywhere between five and sixty-three days. Gillard did not. She wanted the writs out urgently to give the opposition the shortest possible campaign (thirty-three days), a decision she may now be regretting. Nonetheless, in enrolment terms the Labor government has now had its cake and eaten it too. It got the short campaign it thought it wanted, and yet is getting back some of the first-timers who would have missed out on a ballot but for the High Court. The AEC has even said it will phone or contact every lucky enrollee affected by the decision. There has been speculation that the AEC and the government, as official defendants to the case, deliberately ran dead. While neither will be unhappy with the result, that speculation lacks credence. As an independent agency, the commission never takes a stand on the validity of the law it works under. And since the case was launched while the government was in caretaker mode, the solicitor-general would not have received riding instructions from any minister. For civil society there is another lesson from this case. Australia does not have a strong history of civic associations using the law to run test cases or to keep law reform on the front-burner. Get Up!’s success may be changing this. It is also mounting a Federal Court case to argue that electronic submission of enrolment forms is permitted under legislation enabling “e-signatures.” [Graeme Orr’s analysis of the decision in that case, given on 13 August 2010, can be read here.] Institutionally, the ball is back in the parliamentary court. If Labor wins the election, it is likely to push on with its preference – backed by an AEC concerned about the bigger issue of the million or so people “missing” from the roll – to implement automatic enrolment. New South Wales has moved in that direction for state elections, and Victoria also, at least for school-leavers. Unless those state trials tank, there will be pressure on the Coalition to stop simply saying “no” to any electoral modernisation. Victoria is going so far as to trial a form of election-day enrolment, by allowing un-enrolled people to claim a provisional vote at the polling station. (“Provisional” on their entitlement to vote being checked.) The number of electors who will benefit from the High Court’s decision is not insignificant. Yet spread across 150 electorates, they are unlikely to affect the outcome in any but the most ultramarginal seat. The poll analyst Possum Comitatus, who blogs for Crikey, assessed early roll closing as costing Labor less than 0.1 per cent of the two-party vote. If so, its undoing will at most be worth a bit of extra funding for the parties (votes being worth $2.30 each), especially the Greens. But political effect is not the point. In principle every vote is sacred and the whole purpose of the roll is accuracy and comprehensiveness, not being a hurdle to the ballot. The High Court has struck a modest blow for those principles. • Graeme Orr is an Associate Professor in Law at the University of Queensland and author of The Law of Politics: Elections, Parties and Money in Australia (The Federation Press, 2010, forthcoming). He discussed the High Court decision with Damian Carrick on ABC Radio Rowe v Electoral Commissioner 5.6 The High Court case of Rowe was a challenge to the 2006 amendment of the Commonwealth Electoral Act that reduced the close of rolls period. Prior to this change, new electors could enrol, previous enrolled electors could re-enrol, and enrolled electors could update their details in the seven days following the issue of the writs. The close of rolls period for new enrolments, re-enrolments and detail updates had been seven days since the 1984 federal election. 5.7 However, as a result of the changes, for the 2007 and 2010 federal elections new enrolments and re-enrolments had to be received by the Australian Electoral Commission (AEC) by 8 pm on the day of the issue of the writs, and changes to enrolment details had to be received within three days of the issue of the writs. 5.8 The plaintiffs in Rowe were Shannen Rowe and Douglas Thompson. Ms Rowe turned 18 on 16 June 2010 and was not enrolled at the time the election was announced. She did not lodge her completed application with the AEC until Friday 23 July 2010, which under section 102(4) of the Commonwealth Electoral Act, at the time, was required to be lodged by 8 pm on Monday 19 July 2010. 5.9 Mr Thompson was enrolled in the electoral Division of Wentworth, but had moved to a new address in the Division of Sydney in March 2010. He had made unsuccessful attempts to lodge a claim of transfer form under section 101. He subsequently completed a form which was signed on 22 July and it was lodged by facsimile by his solicitor. However, the requirement under section 102(4AA) was that it be lodged by 8 pm on 21 July 2010. 5.10 Ms Rowe and Mr Thompson subsequently commenced court proceedings on 26 July 2010, challenging the constitutional validity of the legislative changes that shortened the close of rolls period. 5.11 On 6 August 2010, the High Court, in a 4-3 decision, ruled the shortening of the close of rolls period to be invalid, as it contravened sections 7 and 24 of the Australian Constitution. The summary of judgment stated: Chief Justice French, Justices Gummow and Bell, and Justice Crennan held that these provisions contravened the requirement, contained in ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution, that members of both Houses of the Commonwealth Parliament be "directly chosen by the people". The Chief Justice considered that the adverse legal and practical effect of the challenged provisions upon the exercise of the entitlement to vote was disproportionate to their advancement of the requirement of direct choice by the people. Justices Gummow and Bell, with whom Justice Crennan broadly agreed, held that the provisions operated to achieve a disqualification from the entitlement to vote and that the disqualification was not reasonably appropriate and adapted to serve an end compatible with the maintenance of the system of government prescribed by the Constitution. Justice Crennan held that the democratic right to vote is supported and protected by the Constitution.2 5.12 In contrast, Justice Heyden stated: The denial of enrolment and voting for an election, for a legitimate reason, does not intrude too far upon the system of voting. It is, and has always been, a part of that system. It reinforces the requirement that persons qualified to vote enrol in a timely way, which is conducive to the effective working of the system. No denial of the franchise is involved. It is not possible, logically, for the plaintiffs to suggest that these provisions are incompatible, but those allowing for a few more days for enrolment are not.3 5.13 As discussed earlier in the report, this resulted in new enrolments, reenrolments and changes to elector details that had been received by the AEC by 26 July 2010 being processed. The AEC advised the Committee that this resulted in an additional 57 7324 new electors on the electoral roll, and some 40 4085 changes to enrolment details being made. 5.14 The Government subsequently gave effect to this decision in the Electoral and Referendum Amendment (Enrolment and Prisoner Voting) Act 2011, which restored the close of rolls period to seven days following the issue of writs. This Act also made amendments to prisoner voting entitlements. 6 High Court of Australia website, http://www.hcourt.gov.au/assets/publications/judgmentsummaries/2007/hca43-2007-09-26.pdf, viewed 3 June 2011. 7 Commonwealth Electoral Act 1918, s. 93(8AA). Roach v Electoral Commissioner 5.15 The entitlement of prisoners to enrol, remain on the roll and vote was another issue considered by the High Court. In Roach v Electoral Commissioner [2007] HCA 43, Ms Vicki Roach challenged the constitutional validity of the 2006 amendments to the Commonwealth Electoral Act that changed the voting entitlement for prisoners. The effect of the amendments removed the entitlement for people serving less than a three year term of imprisonment to vote at federal elections. All prisoners were thus excluded from voting. 5.16 In 2004, Ms Roach was sentenced to six years imprisonment for burglary, including negligent injury and endangerment. She argued that she should have the right to vote. 5.17 In Roach, in a 4-2 judgement, the High Court ruled on 26 September 2007, that: ...the 2006 amendments were inconsistent with the system of representative democracy established by the Constitution. The Court held that voting in elections lies at the heart of that system of representative government and disenfranchisement of a group of adult citizens without a substantial reason would not be consistent with it.6 5.18 It was in 2011, three years after the Roach judgement, that the Electoral and Referendum Amendment (Enrolment and Prisoner Voting) Act 2011 gave effect to this principle, restoring the right to vote to some prisoners serving less than three-year terms. However, this means that persons in similar situations to Ms Roach would still be excluded if serving more than three years in prison. 5.19 Prisoners serving a term of imprisonment of less than three years7 now have the option to remain enrolled for the Subdivision for which they were enrolled when they began their sentence. If not already enrolled, a prisoner serving less than three years is entitled to enrol for: (a) the Subdivision for which the person was entitled to be enrolled at that time; (b) if the person was not so entitled, a Subdivision for which any of the person’s next of kin is enrolled; (c) if neither of paragraphs (a) and (b) is applicable, the Subdivision in which the person was born; and (d) if none of the preceding paragraphs is applicable, the Subdivision with which the person has the closest connection.8 2010 Election and Rowe The 2010 federal election differed in some respects from recent previous federal elections. A federal election had not been held in winter since 1987, and this created certain challenges for the conduct of this election. The decision in Rowe v Electoral Commission effectively restoring the close of rolls period to seven days following the issue of writs resulted in an unanticipated additional workload for the Australian Electoral Commission in the processing of almost 100 000 enrolment transactions. As a result of the High Court decision in Rowe, the AEC was required to process those enrolment applications received after the two original enrolment cut-off dates, but which were received on or before 8 pm on Monday 26 July 2010. 2.11 Processing of those affected enrolment applications was completed on Friday 13 August 2010, resulting in 57 7324 new electors added to the electoral roll, and some 40 4085 changes to enrolment details being made. In addition, and also on Friday 13 August 2010, the Federal Court of Australia upheld the use of a digital signature in completing a claim for enrolment. In Getup Ltd v Electoral Commissioner [2010] FCA 869 (the Getup case) the Federal Court held that a claim for enrolment completed on Getup’s ‘ozenrol’ website and signed digitally by Ms Sophie Trevitt, using a digital pen on a trackpad and witnessed using the same technology, met the requirements of the Commonwealth Electoral Act. Ms Trevitt was subsequently added to the electoral roll and was able to vote on 21 August.7 Following the original close of rolls on 22 July 2010, enrolment stood at 14 030 528 electors, and after the final close of rolls following the High Court’s decision in Rowe v Electoral Commissioner [2010] HCA 46 (Rowe), 14 088 260 electors were enrolled to vote.2 Should we have to vote?The High C