* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Section 4 Seesaws Hello. I`m Lou Bloomfield and welcome to How

Survey

Document related concepts

Angular momentum operator wikipedia , lookup

Fictitious force wikipedia , lookup

Newton's theorem of revolving orbits wikipedia , lookup

Relativistic mechanics wikipedia , lookup

Jerk (physics) wikipedia , lookup

Modified Newtonian dynamics wikipedia , lookup

Rotational spectroscopy wikipedia , lookup

Equations of motion wikipedia , lookup

Center of mass wikipedia , lookup

Relativistic angular momentum wikipedia , lookup

Classical central-force problem wikipedia , lookup

Newton's laws of motion wikipedia , lookup

Mass versus weight wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

Section 4 Seesaws

Hello. I'm Lou Bloomfield and welcome to How Things Work at the University of Virginia.

Today's topic: Seesaws. Seesaws are a simply toy that consists of a long board mounted on

a central pivot. Two riders get on opposite ends of that board, and adjust their positions

until the seesaw balances. At that point then, they can begin to make the seesaw rock back

and forth. Either by leaning toward or away from the pivot, or by pushing on the ground

with their feet.

Mechanically, a seesaw is a lever and fulcrum seesaws also work as a simple example of a

mechanical system with two equilibrium positions one side is stable, while the other is unstable

Levers can be used to exert a large force over a small distance at one end by exerting only a small

force over a greater distance at the other.

Classification

Industry

Weight

Fuel source

Components

Simple machine

Construction

Mass times gravitational acceleration

potential and kinetic energy {mechanical energy}

fulcrum or pivot, load and effort

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lever

When I was a kid, seesaws were everywhere. Any playground worth its salt had a couple of

them. And either at recess or during a birthday party we'd clamber onto the seesaws, one

at each end, maybe one big kid, one little kid, maybe several at each end. And we'd rock

back and forth furiously until our legs wore out, or one of us got hurt. Or we simply wanted

to do something else.

Nowadays, seesaws become rarer and rarer. It seems that either they're risky, or perhaps

modern children don't enjoy that sort of activity as much.

Whatever the reason, they're missing an opportunity to experiment with rotational motion,

balance, levers, and mechanical advantage.

Seesaws turn out to be a wonderful context in which to explore the physics of rotational

motion.

So I've stuck with them, even as they've somewhat abandoned me. If you have a seesaw

nearby, I urge you to experiment with it. Although be safe, because there are ways in which

you can get yourself injured playing with a seesaw. More on that later.

If you don't have a see-saw, well, you can make one yourself. All you need is some object to

serve as a central pivot and a board to balance on that pivot. You adjust the spacings just so

and. Voila, a seesaw.

You can have it rock back and forth, just like the real thing. Actually, that simplicity.

The fact that you can make something like this so easily, explains why seesaws have been

around so long. They're pretty simple to make.

As I suggested earlier, the story of seesaws is also the story of rotational motion, balance,

levers, and mechanical advantage. We'll study those concepts here in the context of

seesaws and then use them repeatedly as we continue to look at how things work.

Before continuing, however, I want to ask you a question to think about. Not to answer, but

something you should have in mind as we work our way through the story of seesaws. It's a

difficult question, one that doesn't have an obvious answer so it's a good prelude to the rest

of the story here on seesaws.

Suppose you and a child half your height lean out over a swimming pool at the same

angle. So here's you, here's the child, and you're both leaning out over the swimming

pool at the same angle. If you both let go at the same moment, so that you begin to

rotate into the pool, which of the two of you reaches the water first?

To help guide us through the science of see saws, we'll pursue six, how and why questions.

How does a balanced seesaw move?

Why does a seesaw need a pivot?

Why does a lone seesaw rider plummet to the ground?

Why do the riders' weights and positions affect the seesaw's motion?

Why do the riders' distances from the pivot affect the seesaw's responsiveness?

How do the seesaw's riders affect one another?

There is one video sequence for each of those questions and a summary sequence at the

end.

And now onto the first question.

Part 1.

How does a balanced seesaw move?

The full answer to that question will require some careful explaining, but a short answer is

that a balanced seesaw rotates steadily about a fixed axis.

Now it's tempting to think that I've just asked a trick question, that a balanced seesaw

doesn't move at all. In fact, that it's horizontal and motionless.

But the real answer to that question is more subtle. Yes, a balanced seesaw can be

horizontal, and it can be motionless. But it doesn't have to be. What a balanced seesaw

does exhibit, however, is rotational inertia. If I set it spinning, it rotates steadily about a

fixed axis.

Up until now, I've talked about a type of motion that takes you from place to place. So, in

the episodes on skating, falling balls, and ramps we went somewhere; from place to place.

In this episode on seesaws, we don't go anywhere. Seesaws are installed in playgrounds.

And they stay there indefinitely. What seesaws do, do, however. Is rotate.

So, the world of motion can divide into two main types. The motion of translation, of

going somewhere and the motion of rotation, spinning in place. And see-saws. They're

about spinning in place.

In the episode on skating, we saw that a skater exhibits translational inertia. The inertia of

going places. And associated with that translational inertia was Newton's first law of

translational motion. Namely, that an object that's free of external forces, moves at

constant velocity.

In this episode on seesaws, we're looking at objects that can exhibit rotational inertia.

When they're at rest, they stay at rest. When they're rotating, they continue to rotate.

Associated with rotational inertia is another Newton's first law, but now it's the Newton's

first law of rotational motion.

In a draft form Newton's first law of rotational motion states that a rigid object that is not

wobbling and that is not experiencing any outside influences, rotates about a fixed axis

turning equal amounts in equal times.

That law has a couple of extra words in it. It refers only to rigid objects and objects that are

not wobbling.

So Newton's First Law of Rotational Motion has relatively limited applicability.

What can you do? Rotational motion simply is more complicated than translational motion

and therefore the Newton's 1st Law in the world of rotation is fairly limited. There are lots

of things that don't that don't follow Newton's 1st Law of rotational motion. Because they

either change shape, or because they're wobbling.

http://physics.bu.edu/~okctsui/PY105%20Lecture_notes/PY105_Fall2009_files/PY1056pm_NewtonLaw-Rotation.pdf

To perfect the draft of Newton's First Law of Rotational Motion, we need to identify the

external influences, and we need better language to describe rotation about a fixed axis

turning equal amounts and equal times.

I'm going to start with the second task.

In the previous episodes, I described translational motion and identified several physical

quantities that are useful for that description. Among those physical quantities were

position and velocity.

In describing rotational motion, there are analogous physical quantities. There is a physical

quantity describing... Angular position. Angular, rotational, it doesn't matter, but there, it's

technically called angular position. And there is a physical quantity describing how angular

position changes with time, and it's called angular velocity.

So, those are the 2 quantities I want to introduce.

1st, angular position.

Angular position is an object’s orientation, and instead of illustrating angular position using

the seesaw, I'm going to illustrate it using my body. So, angular position will describe how

I'm oriented.

I'm going to start with a zero of angular position, which is the starting point, the zero. This

will be my 0 of angular positioning, the orientation that we all agree is the starting point,

facing you.

If I change my angular position, that means that I'm facing some other direction, like this or

this or like this and Like that, and so on. Well, how do you describe, technically,

quantitatively, those various other orientations? How do you do it?

Actually, you need an amount and a direction. You need a vector. So angle position is a

vector quality and here's how it works.

First, the amount is an angle. The angle through which you have to rotate to go from the

zero, namely facing you, to the orientation that you're trying to describe.

For example this, this is the one I'm going to try to describe, facing like this. And the angle

that I have to rotate through to go from the zero, to this, is 90 degrees. From there to

there, that's 90 d-, you know what, 90 degrees right?

So this angular position is 90 degrees. But that's not enough. This is 90 degrees. And so is

this. And so is ……….this……, alright? So there are a bunch of 90 degree angles positions.

We need a direction as well. And the direction of an angular position is the axis about which

the rotation occurs. For example, to rotate to this 90 degree angular position, I need to

rotate about a vertical axis as though I were a toy top being spun. So I'm being spun, there I

go.

So this is 90 degrees about a vertical axis.

But there's an ambiguity. This is 90 degrees about a vertical axis. And so is this. They're

both 90 degrees about a vertical axis.

How do you distinguish them? Well, physicists and mathematicians distinguish them using a

convention known as the right-hand Rule. And the right-hand rule says that if you take your

fingers of your right hand and curl them in the direction in which the rotation occurs. For

example, if I'm going from this to this, the rotation is like that. Then look at my thumb. The

thumb of my right hand, points in the official direction of that rotation, downward.

So in going from 0 to this, I rotated 90 degrees. Downward.

On the other hand, if I go from this to this, my fingers have to be pointing the other way.

My thumb is now pointing up, this orientation this angular position is 90 degrees up.

So the ambiguity is solved by the right hand rule. 90 degrees down. And 90 degrees up.

How about this? That is 90 degrees toward you. And this is 90 degrees towards me.

Final word about angles. The angle part of angular position can be measured in various

units. Up until now, I've been using the unit known as the degree. It's a familiar unit of

angle; this is zero degrees, 90 degrees, 180 degrees, 270, 360.

Another possible unit of degree is the rotation. Full rotation: This is zero, quarter rotation,

half, three quarters, full rotation.

But the unit that mathematicians and physicists normally use to describe angles, is neither

of those two.

It's the radian. And there are two pi radians in a full rotation where pi is the mathematical

constant. Three point one four one five nine (3.14159) and so on. And that is the natural

unit of angles. There are reasons why it's particularly useful in physics. Whether you use it

or not, doesn't matter.

Pick your unit of angle and stick with it. You're fine.

So you can describe this angular position as 90 degrees down. Or quarter rotation down.

Or pi over two radians down. They're all the same.

That's angular position, but that by itself doesn't help us redraft Newton's first law of

rotational motion. We need to look a little deeper.

We have to look at how angular position is changing with time, because when something is

actually rotating its angular position is evolving, changing with time. And we need the next

physical quantity which is angular velocity.

Angular velocity is the rate at which angular position is changing with time.

So right now my angular position is not changing with time, so my angular velocity is zero.

But if I begin to spin, then my angular velocity is no longer zero. For example, if I turn like

this I am now turning about 90 degrees per second. And the same right hand rule applies.

I'm turning such that my fingers curl like this and my thumb points out. This is an angular

velocity of 90 degrees per second down. Also pi over two radians per second down.

Let me stop.

Let me show you 90 degrees up, here it is. Alright, I could show you 90 degrees toward you.

Yeah 90 degrees per second toward you but that's, I'm going to run out of ability to do this.

But I hope you get the point. That angle velocity describes how an object is rotated, that is

how fast it's going through angles, and also the axis about which it's spinning and finally,

using the right hand rule, the specific direction of its spin around that axis.

So you should be able now to distinguish 90 degrees per second down from 90 degrees per

second up.

That now, that physical quantity, angular velocity will be useful in redrafting Newton's first

law, rotation motion. Because we can rewrite the rotating about fixed axis, turning equal

amounts in equal times as, having constant angular velocity.

If I'm turning 90 degrees per second down and staying that way, my angular velocity is

constant.

Alright, that brings us to the other task. Which is identifying the external influences that

show up in Newton's first law of rotational motion. And those external influences are

twists. Technically, they're known as torques. A torque is the influence that upsets

rotational inertia. And therefore, violates Newton's first law of rotational motion.

We'll look more at torques. But just so that you know what a torque is. Let me show you

what happens when I exert a torque on this seesaw. To do it, I twist the see-saw. So I'll

grab the see-saw from the front, and I will twist. And suddenly, it changed its angular

velocity. - It started with an angular velocity of zero, let's get zero there. And it's now, at

present it is a rigid object that's not wobbly, it's obeying Newton's first law of rotational

motion.

But if I come in with an external influence of the right type, namely, a torque. While I'm

exerting that torque, it is not following Newton's first law of rotational motion. It changed

its angular velocity. So, we can now state Newton's first law of rotational motion in all its

glory.

A rigid object that is not wobbling and that is free of external torques rotates at constant

angular velocity.

That brings us to a question.

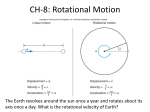

What influence or effect causes the earth to rotate steadily?

approximately 24 hours.

Turning once every,

The Earth is rotating because it exhibits rotational inertia. It's experiencing essentially no

torques, and therefore, it rotates according to Newton's 1st Law of Rotational Motion,

namely - It's a rigid object that is not wobbling, it is not experiencing any external torques,

so it rotates with constant angular velocity. That angular velocity is approximately one

rotation per 24 hours. About the North Pole so that the rotational axis points from the

centre of the earth up to the North Pole and that's the way the earth rotates.

So we see a balanced seesaw is not necessarily motionless or horizontal. What we can say

about that balanced seesaw however, is that it exhibits rotational inertia. If it's motionless,

it remains motionless. If it's rotating, it continues to rotate.

Because it's a rigid object that's not wobbling, it exhibits a particularly simple type of

rotational motion. Namely, constant angular velocity. So right now, the angular velocity of

this balanced seesaw Is 0. But if I twist it, and during the twist it's not rotationally inertial

and so, I'm violating Newton's 1st Law of rotational motion by doing the twist. Here we go,

I'll give it a twist. And now it's once again rotationally inertial. It's obeying Newton's 1st Law

of rotational motion. It's a rigid object that is not wobbling, it's free of external torques, so,

it rotates at constant angular velocity, apart from some air resistance problems here.

The point is, it's rotating right now, not because something is twisting it, but because

nothing is twisting it. It is its nature, and the nature of objects in our universe to keep

rotating in the absence of twists. They keep going. That's rotational inertia.

So, in a normal see-saw that perpetual rotation isn't possible, because during the rotation,

even when it's balanced initially, it eventually touches the ground. And at those moments

when it touches the ground, the ground exerts torques on the seesaw. It twists the seesaw

and therefore takes it out of Newton's First Law of Rotational Motion, violates Newton's

First Law of Rotational Motion, and new things happen. And those new things, basically the

consequences of torques... Are a subject for the next video.

Part 2.

Why does a seesaw need a pivot?

The answer to that question is that the pivot prevents the seesaw from undergoing translational

motion, while leaving it free to undergo rotational motion. Without a pivot to support its weight

and that of its riders, the seesaw would fall. And while two children might find it exciting to jump

out of an airplane seated at opposite ends of unsupported seesaw, that idea is unlikely to be popular

with their parents.

The physics will be fabulous but I'm not going to film it. I'm going to leave that for children who

enjoy extreme recess. Instead, I'm going to show you how an unsupported and riderless seesaw

moves.

Basically, I'm going to throw the seesaw through the air and we'll watch its motion. For obvious

reasons, I'm not going to use a large seesaw, I'm not even going to use one as big as this. But even

so, even with a small seesaw board, or a pretend seesaw board, I need more room, so, let's go

outside and have some fun.

I'm going to throw a riderless, unsupported seesaw.

Well that sure was quick.

But this is video so I can show you that throw again. And this time I can slow it down to one tenth its

original speed. Moreover, I can make the images of the seesaw linger on the screen so that you can

see all the previous images as the seesaw goes through its travels. Now, because the camera takes

30 frames per second, those images will be separated from one another by a thirtieth of a second.

Here we go.

The same throw, slowed down to one tenth its original speed, with all the previous images of the

seesaws lingering on the screen.

Seeing all those image of the seesaw is pretty, but how do we make sense of the seesaw's motion?

It turns out that the seesaw is doing two things at once, it's translating and it's rotating.

Translational motion.

Well, its centre of mass is traveling in the arc of a falling object as though it were a tiny ball located

at the centre of mass, that's traveling in the arc that we're familiar with for falling balls. At the same

time, the seesaw, which is an extended object, is rotating about its centre of mass, its natural pivot.

And, it's doing these two things at once: the translation motion of a falling object located right at its

centre of mass, and the rotational object. Motion of an extended object rotating about its natural

pivot. Its centre of mass.

So I'm going to show you that same video again, same throw. Once again, at one tenth normal

speed with all the previous images of the seesaw board in view, but this time, I'm going to show you

the arc of a falling object, and I picked the arc just right so that the seesaw's centre of mass will

travel along that arc, as the seesaw rotates about its own centre of mass located on that arc.

A seesaw has it's centre of mass located pretty much in its geometrical centre. So, the motion we

saw had the centre of the board travelling in the arc of a falling object as the rest of the board

rotated about its geometrical centre.

But not all objects have their centres of mass at their geometrical centres.

For example, a mallet. Nearly all of the mass of this mallet is in its head. The handle is almost

nothing. So, when I throw this mallet, the head will travel in the arc of a falling object because the

centre of mass is almost dead centre in that head. So you'll see that centre of mass travel in the arc,

and that's the head. At the same time, the handle, which is almost an insignificant contribution of

mass, will rotate about the centre of mass, and the arc'll look a little different.

So, now I'm going to throw the mallet. Here we go.

This rubber mallet has most of its mass in its head. Once again, that was very quick. So I'm going to

show you the same throw. But this time, I'm going to slow it down to one tenth its original speed.

And I'm going to let all the previous images of the mallet linger on the screen. So you can watch the

path the mallet takes. And its orientation while it's taking that path.

It's already pretty obvious that the mallet is following the arc of a falling object as its rotating. But

just to make that crystal clear. I'm going to show you the same throw again, one-tenth its original

speed, with all the images of the mallet lingering on the screen, but this time I am going show the

arc of a falling object that travels along in the path taken by the mallet's centre of mass.

So you see, when you throw something, and it becomes a falling object. That is, it's experiencing

only one force, its weight, its motion is actually fairly simple. The object's centre of mass travels in

the arc of a falling object. As though it were a simple thing like a falling ball. At the same time, the

rest of the object may be rotating about that centre of mass. The object's natural pivot. So the

object is doing two things at once. It's translating in the arc of a falling object as it's rotating in the

manner of an object that's just simply free to rotate about its own natural pivot. Its centre of mass.

This may look like an ordinary beach ball, but it's not. Watch how it moves.

It's hard to catch.

Why does this beach ball move in such a crazy manner?

This beach ball has its centre of mass located far from its geometrical centre. There's a container

over here on the side of the beach ball that's full of water so that most of the mass of the ball is

located here where I can touch. As a result, the centre of mass is here on the surface of the ball.

And when I throw the ball, and it becomes a falling object, it's that centre of mass that travels in the

arc of a falling object. The rest of the ball comes along for the ride. And it rotates about its centre of

mass, its natural pivot. And therefore about one surface, one side of the ball. So that wobbly

motion you're seeing is the ball rotating about the side of the ball, its natural pivot where the centre

of mass is located.

You can begin to locate a small object's centre of mass by setting it on a surface to support its weight

and then giving it a spin. It naturally spins about its centre of mass.

So, what I can say in, for this basketball is that the centre of mass of the basketball lies somewhere

on this rotational axis. It's spinning about a line, passing from top to bottom of the ball, and the

centre of mass is located on that line. I can't tell you for sure where along that line is unless I rotate

the ball and spin it again, rotate the ball and spin it again, but eventually, I could pin down the fact

that for a basketball, the centre of mass is pretty much dead centre in the geometrical centre.

That's true of a basketball. But not so true for knife.

How do you find the centre of mass of a knife?

Give it a spin.

It's right about there. It's somewhere, that's the point that's staying put as it spins. It's spinning

about that point. So I can tell you the centre of mass is somewhere ...between my two fingers.

To pin it down further, I'd have to spin the knife about another axis.

Can I do it?

Ooh. I can. So now I've really pinned down the centre of mass of the knife. It's really right there in

the middle of this metal piece.

Well, for a seesaw, you do the same thing. So here's a seesaw board. You give it a spin. The point

that's trying to stay put is right about here. So that's, that's the centre of mass. Somewhere

between my fingers. And that's where the pivot goes when you make the seesaw into a real

rideable seesaw.

And I can pull one of those up. Here it is.

The rideable seesaw if you're very, very small. Is supported right at its centre of mass, and therefore

pivots naturally about that point. So we're supporting it right at its centre of mass, and allowing it to

undergo rotational motion about its own natural pivot.

When examining rotational motion, it's technically necessary to specify the centre of rotation. That

is, the point about which all the physical quantities of rotational motion are defined. We're free to

choose that centre of rotation. But some choices are better than others.

For example, if I'm rotating like this and we want to describe my rotation as simply as possible using

the physical quantities of rotational motion, the most obvious choice for a centre of rotation about

which to build our language is my centre of mass, 'cause that's the point about which I'm pivoting.

So, in this case, we define the centre of rotation as located at my centre of mass.

So for example, my angle of velocity now is about 90 degrees per second up, remember the right

hand rule, about my centre of mass. So about my centre of mass, is pinning down the centre of

rotation about which our language is built. But if I'm rotating not about my centre of mass, but

about my thumb, watch this.

Here we go.

I can pivot about things other than my centre of mass. I need help to do that. But I can do it, and

I'm now pivoting about my thumb. So, it makes good sense to define that as our centre of rotation

and to say that I am currently rotating. My angular velocity is about 90 degrees again, up, about my

thumb. That's the centre of rotation.

Well, by now I hope you can see that while choosing a centre of rotation is necessary to define the

physical quantities of rotational motion, stating that centre of rotation explicitly every time you use

1 of those physical quantities is a nuisance, and I'm going to stop doing it. Instead I'm going to

assume that the centre rotation that we have in mind is obvious, unless it's not, in which case I will

say it.

So, for this case of a seesaw mounted with a pivot passing right through its centre mass, its own

natural pivot, that’s an obvious choice for our centre of rotation. Right here in the middle of the

board where the pivot passes through the centre of that board's centre mass. That's the obvious

choice for the centre of rotation. And we’ll assume for the remainder of this story, that every

physical quantity of rotation is defined about that point. So, instead of adding language now to all

our physical quantities of rotation for the seesaw, let's put some riders on it.

And that's the job for the next video.

Part 3.

Why does a lone seesaw rider plummet to the ground?

The answer to that question is that the lone rider produces a torque on the seesaw and causes it to

undergo angular acceleration. The seesaw rotates such that the rider descends toward the ground.

And hits it.

There are several ways of examining this situation. So I'm going to follow the path that I think is

most straightforward.

The rider's weight gives rise to a torque on the seesaw. And since the seesaw is no longer

rotationally inertial, its angular velocity is no longer constant. Instead, that angular velocity changes

with time, and the rider soon plummets to the ground.

But those observations give rise to two more questions.

How does the seesaw respond to torques, and what is the origin of this particular torque?

So let me start by looking at the seesaws response to torques.

When the seesaw is experiencing no outside torques it's covered by Newton's first law of rotational

motion. So it rotates at constant angular velocity, like this.

But once there is a torque acting on the seesaw, the seesaw is no longer covered by Newton's First

Law of Rotational Motion. And its angular velocity is no longer constant. Instead, its angular

velocity begins to change with time. The seesaw undergoes angular acceleration. Angular

acceleration is another vector physical quantity of rotational motion, and it is the rate at which

angular velocity is changing with time. Like ordinary acceleration, translational acceleration, it's a

subtle quantity. It's hard to see. You have to look carefully. It takes three glances to see

acceleration and it takes three glances to see angular acceleration. So I'm going to illustrate angular

acceleration with my body and hope that you can see it happening.

So here we go, let me start, motionless, rotationally motionless. That is my angular velocity is 0. If I

change my angular velocity, during the time over which that angular velocity's changing, I am

undergoing angular acceleration.

So here we go.

I'm going to undergo angular acceleration, and then I'm going to stop undergoing angular

acceleration, and watch what happens. Here goes the angular acceleration; it's going to be...

Up.

Right hand rule again. I'm going to rotate. Here we go.

Shoop.

Okay, I did it. It’s over. I am now coasting rotationally, at constant angular velocity. But when I first

got started I was undergoing angular acceleration. If I don't undergo angular acceleration again, I'm

going to keep spinning here forever, and this will make me very dizzy. So I'm going to undergo

angular acceleration downward in a moment.

Ready?

Get set, whoop, there I did it.

So during those two extended moments when I changed my angular velocity I did it by way of

angular acceleration.

I'll show it to you again. I'm going to do Angular acceleration upward for about a quarter of a second

and then, I'm going to do Angular acceleration downward for about a quarter of a second and come

to stop.

Ready?

There. Now, I'm coasting and now.

So, the angular acceleration portion of that situation was during the changes in my angular velocity.

Coming back to the seesaw then, the angular acceleration is absent now.

Ready, get set, there it is. There were a lot of angular accelerations there at the bottom, but they

initially kicked in, the first angular accelerations Kicked in when the rider got on the seesaw. Right

now.

So we see, a torque causes a seesaw to undergo an angular acceleration.

But what if there's more than one torque, acting on that seesaw at the same time?

In that case, those torques add together to become a net torque, and the net torque is what causes

the angular acceleration. So for example if I've got 2 riders hopping on to the seesaw at once, the

seesaw can't respond with several separate angular accelerations at the same time, it only has 1.

Instead it responds to the net torque, produced by those 2 riders.

Well, if net torque causes angular acceleration, the question comes up is, how much angular

acceleration?

It turns out that the seesaw's angular acceleration is proportional to the net torque acting on it. So

if a gently net torque acts on a seesaw. It undergoes a small angular acceleration. But if a large net

torque acts on the seesaw, it undergoes a large angular acceleration. But there's a second factor

involved in determining the seesaw's angular acceleration, the seesaw's rotational mass.

Rotational mass is the measure of an object's rotational inertia, its resistance to undergoing

angular acceleration. Now traditionally that physical quantity is called moment of inertia and it has

various complexities to it. They're beyond the, the scope of our little discussion here. Not relevant

really to seesaws. So rather than trying to have you remember a name like moment of inertia, with

its complexities, I'll make our lives simpler by simply calling it Rotational mass. That conveys the

characteristic that it's a mass like thing, it's a resistance to acceleration of some form. In this case,

rotational acceleration.

So, this seesaw has a certain rotational mass, a certain resistance to angular acceleration. So if I

exert a certain torque on it, it responds with a specific angular acceleration. And I go back to, to

putting a rider. So, my little rubber stopper rider is here. If I put a certain rider on this seesaw and

let it undergo angular acceleration, well, it undergoes rather rapid angular acceleration, and down

goes the rider.

But I can increase the rotational mass of this seesaw. By adding a second board. When I do this, I'm

increasing the rotational inertia of the seesaw. Try to glue it and tape it in place. And now, it's less

responsive to the same torques as before.

In this case, if I put 1 rider on, it undergoes angular acceleration, but not as much. Overall, the

seesaw's angular acceleration is proportional to the net torque acting on the seesaw. And also

inversely proportional to the seesaw's rotational mass.

Those two observations form the basis for Newton's Second Law of Rotational Motion, which

states that an object's angular acceleration is equal to the net torque acting on that object divided

by that object's rotational mass.

I'm going to ask a question about angular acceleration, but I'm going to do it in the context of a

bicycle wheel that I can hold in my hands. At present the bicycle wheel is motionless. And I'm going

to do three things to it, in sequence.

First, I'm going to start it spinning.

Second, I'm going to turn the wheel all the way around like this, so it's spinning in the opposite

direction.

And now as a third thing, I'm going to stop it from spinning.

The question is, during which of those 3 steps was the bicycle wheel undergoing non-zero angular

acceleration?

All three steps involved angular acceleration of the wheel. When I started it spinning it went from

having an angular velocity of zero to having an angular velocity toward you. Remember the right

hand rule here. When I pivoted it around like this, I reverse the direction of the wheel’s angular

velocity from toward you to toward me. That's angular acceleration. I had to make the wheel

undergo angular acceleration to reverse its direction of rotation. And finally, when I stop the wheel

from spinning, I take its angular velocity from towards me to zero.

So, all three steps require the wheel to undergo angular acceleration.

So, we see that a seesaw responds to a net torque by undergoing angular acceleration.

Why then does a low rider sitting at the end of the seesaw board exert a torque on that board?

After all, the rider has a weight, which is a force, and if I hold the seesaw in place now, the rider and

seesaw are pushing on each other with forces. The seesaw to support the rider's weight and the

rider pushing back on the seesaw in response.

It's all forces out here. Where does the torque come from?

Well it turns out that forces and torques are related and that a force can produce a torque and a

torque can produce a force.

To see how that all works, let's go experiment with a door....because doors are a wonderful example

of rotational motion and the use of a force to produce a torque.

So here I am outside the physics building, opening and closing doors in a light rain. The things we

do for science.

Doors are a nice example of rotational motion. After all, they don't go anywhere. They simply

rotate open and closed about their hinges. They have all of the characteristics we've come to expect

of rotating objects. They have angular positions, they have angular velocities, and they even have

angular accelerations.

But that brings us to the issue at hand, which is when you open a door you do it by exerting a force

on the door handle. And yet the door undergoes angular acceleration.

Well, angular accelerations are produced by torques, not by forces. So how is it that a force exerted

on the door handle produces a torque on the door?

To show you how that works, I first have to define a centre of rotation. Now, the obvious place to

put the centre of rotation is somewhere along the hinge line. Because that's the line about which all

the door's rotation occurs. But I have to be more specific than that. Because centre of rotation is

actually a point. Not a line. So I'm going to put the centre of rotation in line horizontally with the

door handle for reasons that we'll come to eventually. And that's going to be our centre rotation

right there on the hinge line aligned nicely with the door handle.

Having done that then, let's look at ways in which not to produce a torque about that centre

rotation, starting with a force. So these are all the unsuccessful ways to try to open a door, some of

which you may have encountered by accident.

So, first unsuccessful way to produce a torque, starting the force, is to push the door handle toward

the centre of rotation. So I'm pushing right at that centre of rotation.

No effect. I'm producing no torque.

How about reversing my force? Instead of pushing toward the centre of rotation, let me pull away

from the centre of rotation.

Also, no luck. Doesn't do anything.

So we see that pushing toward or away from the centre of rotation is unsuccessful. How about

pushing on the centre of rotation? Let me come over here to the centre of rotation and push right

on it. I'll try to pull right on it, all the kinds of forces, none of it works.

So you can't produce a torque by exerting your force toward, away from or on the centre of rotation.

Okay. Now it's time to be successful. We can only take so much frustration. So now, I'm going to

exert a force out here on the door handle, not toward or away from the centre of rotation, but at

right angles to a special line. It's actually a vector. It's called the lever arm. And this is what the

lever arm is. The lever arm is going to be the vector that extends from the centre of rotation to the

point at which I'm going to exert my force. Namely on the door handle.

So there is a vector that points along this line to this point here. It has a length of about 1 meter, like

that and its direction is exactly to your left. And I'm going to exert my force, not along that vector

or, you know, with it or against it, but at right angles to it, perpendicular to that lever arm. I'm going

to exert my force toward you, and watch what happens. The door undergoes angular acceleration

and begins to rotate open.

That is how to produce a torque starting with a force. If you exert your force at a lever arm, from

the centre rotation, that is the vector that extends from a centre of rotation to where you exert your

force. And you exert your force at perpendicular to that lever arm. Then you produce a torque.

And the torque has a specific direction. Its direction follows yet another right hand rule. If you take

your right hand and extend your index finger in the direction of the lever arm towards your left

right now. And then you sweep the index finger of your right hand in the direction of the force

which is towards you. So that's the sweep. Look what my thumb is doing. My thumb is pointing

up. That is the direction of the torque I produced in pulling toward you on the door handle.

The lever arm is that direction. The force is toward you. The torque I exert is up, and so it causes

upward angular acceleration in the door, which swings open.

Now the amount of that torque that I produce depends on two things.

One is how much force I exert. The torque is proportional to the force I exert. A gentle force

produces a gentle torque. A big force produces a big torque. So, that's the first observation.

Second observation is, the length of the lever arm matters. The torque I produce is proportional to

the length of that lever arm. Here I have a lever arm about that long, but if I go inside and I push

near the hinges, I can make the lever arm very short; and watch what happens.

That was hard.

So, I'm exerting my force here, very close to the pivot, therefore at a very short lever arm, and I'm

obtaining a very small torque until I really crank up my force.

We can combine these observations to relate the force to the torque it produces, quantitatively.

That torque is equal to the lever arm times the force. Where only the component of force that is

perpendicular to the lever arm is included. And where the torque is in the direction determined by

the right hand rule.

So in this case if the lever arm is pointing to your left and the force is pointing toward you, the

torque is up.

Now this door is complicated because it has a closing mechanism, like many doors. It has a system

to try and keep that door closed when you leave it alone. So it's not free to exhibit rotational inertia

and has all kinds of its own trouble and I had to overcome that resistance, that mechanism trying to

keep the door closed. That's a lot easier to overcome if I'm out here with a big lever arm. I can exert

relatively gentle force on the door handle and get the door to open despite the closing mechanism.

If I try to push very close to the hinges, that closing mechanism is hard to beat.

And you may have had this experience that if you go to a door that isn't very well labelled and you

have to push it open andyou can't tell which side of the door has the hinges. If you push near the

hinge side of the door, the door doesn't open very easily. It's very resistant to opening because

you're producing so little torque with your force. You need to go out to the other side of the door

where you have a big lever arm to work with and therefore can really create a lot of torque with a

small force.

To produce a torque with a force then, all we need is a lever arm.

For an unconstrained seesaw like this, one that can rotate in any possible direction, the options are

limitless.

I'm going to choose as our centre rotation the seesaw's centre of mass just for convenience here,

right about there. And now, let me show you a couple of torques. Things you've seen before,

maybe some you haven't.

If I come out here to a lever arm towards your left and then I push down with my force, which is at

right angles to that lever arm or, in fact I don't have to be perfectly right angles I have to just have to

have some component that's at right angles to the lever arm. And I push down, I cause an angular

acceleration toward you. Right hand rule again.

On the other hand, if I come out to a lever arm, same lever arm. But I push my force towards you.

Watch what happens. I cause angular acceleration up. And if I come out to a level arm toward you,

very short one but it's there, and push down, I caused angular acceleration to your right. I flipped

the board like that.

Well. This is exciting, but very complicated. There are too many options with our unconstrained

seesaw. So fortunately, we're going to focus on a constrained seesaw, one that has a pivot shot

through the centre that forces it to rotate in a very simple manner.

This seesaw board down here cannot do this kind of rotation, or this kind of rotation. And so, it

operates in a more simple fashion, like this.

And it still exhibits the same sorts of behaviours. To produce a torque on this seesaw, I come out to

a lever arm and push at right angles, or partly at right angles to that lever arm down and I cause

angular acceleration toward you. Because my torque was toward you.

We've seen how to produce torques with forces in the context of doors, in the context of seesaws.

But what about another important household use of torques, putting in or taking out screws or

bolts?

You rotate a bolt into place and you rotate it the other direction to take it out of place. Well

suppose you have a big bolt like this that has rusted in place, and you're trying to get it out but it

won't turn when you grab it with your hand and try to twist. You need more torque. So, in that case

you get a wrench.

This is a device, and you will have to figure out how it works. This is a device that when you put it on

the head of the bolt, it allows you to produce more torque. And by now, you should be thinking

about how this works.

But what if this is really, really stuck?

And you need a bigger wrench?

Well, that's already a pretty big wrench, you think. And you're probably thinking that I'm going to go

over and get this wrench. To show you the bigger wrench.

But no. I have in mind this wrench. And so we take this wrench, put it on our stuck bolt. And lo and

behold, it's a lot easier to produce a large torque on that bolt and remove it from wherever it's

stuck.

The question then, is this, why is using this larger wrench more effective? Why does it enable you

to remove that bolt when this wrench didn't to the job?

This wrench has a longer handle, and it provides a longer lever arm with which to produce a torque

using a force. So when you come out here to the end of the handle and push perpendicular to that

handle and therefore perpendicular to the lever arm, your force produces a larger torque as

compared to this wrench. There's just not as much length here to work with. It's got a shorter lever

arm and so when you push on the handle of this wrench with that shorter lever arm your force

produces less torque.

So we see, whenever a lone rider goes out to a lever arm on the seesaw and sits down, the rider's

weight gives rise to a torque on the seesaw that causes it to undergo angular acceleration, such that

the rider ends up pretty much sitting on the ground. The rider's weight is a force and that weight

causes the rider to push on the seesaw with a force, but the force acting at a lever arm from the

centre rotation produces the torque that causes all this to happen.

Pretty much the only place a single low rider can sit or stand and not produce a torque on the

seesaw is exactly on top of the pivot, which is kind of an interesting place to stand. And I must admit

to having done that myself, from time to time. But it's much more fun to have 2 riders on a seesaw,

and that is the subject for the next video.

Part 4.

Why do the riders' weights and positions affect the seesaw's motion?

The short answer to that question is that they affect the net torque on the seesaw, and therefore

the seesaw's angular acceleration. In most cases, the riders of a seesaw position themselves so the

net torque on the seesaw is 0 or very nearly 0. As a result, the angular acceleration of the seesaw is

either 0, that is, its coasting rotationally. Or it's just got the smallest amount of angular acceleration.

Well, that then requires a longer explanation.

How does that come about? You put riders on the seesaw; why don't they produce enormous net

torques?

So we know that if we put one rider on the seesaw, that rider, because of the rider's weight, the

rider pushes down on the seesaw over here, on your left... That's to the lever arm from the pivot. It

produces a torque and boom, the seesaw undergoes rapid angular acceleration such that, that rider

drops to the ground.

But what if we put two riders on the seesaw simultaneously?

And what I'm going to do is I'm going to position them very carefully.

And look. The seesaw is experiencing very little angular acceleration, so the net torque on it is either

zero or very near zero.

How did that happen? Aren't these riders producing big torques on the seesaw?

There are two of them.

Ahh! Glad you asked that question.

Here's the story, this is now the longer explanation to the question that's prompted this video.

That rider because the rider's weight is pushing down on the board, over here to your left, the lever

arm that, that rider’s force is using to produce a torque, points towards your left. Here it is, and

using the right hand rule now, we can see the direction of the torque produced by that rider. The

torque, we follow the lever arm and we roll, I roll my finger down in the direction of the force and

my thumb is pointing toward you. That is the direction of a torque, produced by this seesaw rider.

Let's come over to this seesaw rider. I need my right hand again. I can't swap hands or I'll get the

wrong answer. So, that rider by virtue of his or her weight, is pushing down on the seesaw board.

The lever arm with which that rider is producing a torque now, points to your right.

So, there it goes. And now I turn my index finger in the direction of the force. And lo and behold, the

torque produced by that rider is away from you. So these two torques are in opposite directions.

This rider is producing a torque toward you. This rider is producing a torque away from you.

When we add those two torques, and they are the two torques acting on this seesaw, they sum to

zero or very nearly zero. And that's how it is that when I let go of this board and allow it to show you

its angular acceleration there's almost zero. If there is a little bit, and there is, I can adjust the

distance of one of the riders from the pivot.

This riders producing a little too much torque. And now I, I move it toward the pivot, still a little too

much torque. So I move it a little closer to the pivot, and now that rider's producing almost just the

right torque. Let me move the rider in a little closer and now this rider's producing too little torque.

I have adjusted the rider's positions, that is the lever arms they're using, to show you that we can go

all the way from almost perfect balance, and I'll talk about balance in a minute, with that rider

dominating a little bit, to almost perfect balance with that rider dominating a little bit. And

everything in between, including in principle, perfect balance where there's zero net torque on the

seesaw.

Actually, balance is an interesting concept. The balance that we talk about in the context of a

seesaw, and many other objects that teeter back and forth like a seesaw, is a situation where

gravity produces no torque on the object. So, when this seesaw is balanced it's experiencing 0

torque due to gravity. I can come in and change things. I'm here, very carefully adjusting positions

in order to try get this situation.

This seesaw is almost perfectly balanced. Meaning it's experiencing almost 0 torque due to gravity.

And that is the normal situation for a seesaw, and riders, they like that situation because a balanced

seesaw is free of torque, this assumes nothing else is exerting torques on it, and it will turn at

constant angular velocity. It is an object that obeys Newton's First Law of Rotational Motion. And

it's not wobbling, it's rigid, assuming the riders don't change their positions.

And therefore, in the absence of any torque, and there's no gravitational torque on a balanced

seesaw, it turns a constant angular velocity. So, the reason the riders have to adjust their positions

very carefully and their weights are important as well, is because they are trying to sum their

torques to zero, and how they place themselves matters.

If, for example, the two riders have, essentially identical weights, and these two riders do, they need

to sit at equal distances from the pivot because the torque they produce, after all, is the product of

the force they exert on the seesaw times the lever arm they have to work with.

There's some subtleties in here with regard to the angles involved between the lever arm and the

force but in this situation we can really ignore those. The forces and lever arms are essentially at

right angles to each other, and our lives are simple.

So these two identical riders, seated at identical distances from the pivot, produce identical but

oppositely directed torques, and the seesaw balances.

What if we have a heavier rider around, though?

So instead of this rider, we bring up one. And this is made of steel. This is heavy stuff. So I'm going

to put this rider in.

If I put this rider out at the same distance as the rider on your right, it completely dominates, and I

run the risk of tossing this rider. This is one of the flaws with seesaws, it's easy for one of the riders

to become an astronaut, when a very heavy rider gets on the seesaw and does that to it.

But this rider cannot sit that far out from the pivot. Too much lever arm for a large force, and

therefore this rider dominates it, and produces a torque that, that one cannot compensate for. So I

have to bring the heavier rider in close.

How close? Pretty close.

I'm almost at balance. There we are, this is balance. Alright? It's as close as I'm going to get. And,

again, the net torque on the seesaw is zero, or pretty close to zero. And, you'll notice that now the

lever arm with which this rider is producing the torque, is quite short because this one weighs a lot,

so big downward force, short lever arm. And that is balancing, or cancelling out the torque due to

this one, which is in the opposite direction, but it's produced by a smaller force acting at a larger

lever arm.

So this is common in playing on a seesaw when you have two children of significantly different

weights. They have to sit at different distances from the pivot. The heavier child sits close to

produce a certain torque, and the lighter child sits far from the pivot to produce an equal amount of

torque but in the opposite direction.

Well, that brings us to a question. And the question is this.

Can two riders, and we can adjust their weights as you like, ever sit on the same side of the

seesaw, and still balance the seesaw?

Two riders cannot sit on the same side of the seesaw, and expect the seesaw to balance. That's

because those two riders produce torques in the same direction about the pivot. Their forces are in

the same direction, their lever arms are in the same direction, so their torques are in the same

direction. And when you add those torques, they sum to something larger than each one

individually. So you get a lot of torque on the see-saw, and it’s terribly unbalanced.

In order to balance the seesaw, the two riders, or however many you want to put on the seesaw,

have to distribute themselves on opposite sides of the pivot so that their torques cancel one another

and eventually, if you do it all right, they sum to zero and the seesaw is rotationally inertial. It has

zero net torque on it and no angular acceleration. It coasts rotationally.

There are two seemingly different ways to think about the balanced seesaw situation.

The first way is the way we've been doing. Where this rider produces a torque, that rider produces a

torque, the two torques sum to zero and as a result the seesaw experience zero torque due to

gravity. It's balanced.

The second way to think about this situation is in terms of a concept known as the centre of gravity.

Now centre of gravity is the effective location of an object's weight. I have one. You have one.

These riders have one. Even the seesaw board has one.

This rider's centre of gravity, that is where its effective weight is located, is pretty much at its centre.

Same with that rider. The seesaw board's centre of gravity, the effective location of its weight, is at

its middle. Right there. And that might make you think that centre of gravity, which is here, and

centre of mass, which is here, are the same idea.

Centre of mass, centre of gravity, aren't they the same?

They're not. They happen to coincide for all objects here near the earth's surface. Celestial objects

violate this concept for complicated reasons that I'll leave for another day. But small objects do

have their centres of gravity at the same locations as their centre of mass, but they're different

concepts.

Centre of mass is the effective location of an object's mass. It's natural pivot. We watched centres

of mass in action when I threw various wobbling objects or sticks and so on through the air and

you'd watch the centre of mass was traveling in the arc of a falling object. That's the mass moving

and the inertial properties of the object in play. So, centre of mass is all about inertia in motion.

Centre of gravity is about forces and it’s forces of gravity. It's got to do with gravity. If there's no

gravity around, centre of gravity means nothing. So it's the effected location object's weight.

The fact that weight is proportional to mass here near the earth's surface, means that centre of

gravity and centre of mass share the same location. But they're different concepts and so if you're

dealing with the inertial aspects of an object, you're probably paying attention to the centre of

Mass.

If you're dealing with the gravitational or weight aspect of an object, you're probably dealing with

centre of gravity.

So, back to the situation here.

We have objects with various centres of gravity and that brings us to an observation that this entire

structure, two riders on a seesaw is, we can consider it as a single object. Where is its centre of

gravity? That composite object.

And it turns out that this overall object's centre of gravity is located right above that Pivot. And it's

being pulled straight down, like the centres of gravity are pulled straight down. They're gravity after

all, right? The forces of gravity are toward the centre of the earth. It's being pulled straight down

right towards the pivot, the centre of rotation.

And as we've seen before, forces that act toward the centre of rotation produce no torque about

the centre of rotation. So, this seesaw is balanced in two ways you can think of it:

One is in terms of the individual riders producing torques that sum to zero.

The other way, which is kind of cool, is that the riders and seesaw together have a centre of gravity

located vertically above the pivot. And therefore, the force of gravity acting on this entire structure

acts right toward the pivot and produces no torque. It's along the lever arm and produces no

torque.

So Annie and Megan here are riding a real seesaw, not one of the little things I have in my lab. And

they’re balanced right now.

Can you show us this?

It takes delicate adjustment, but Megan's distance is just right from the pivot, the pivot's right here.

Annie’s distance is just right from the pivot, they've adjusted it, so the net torque on this thing is as

close to 0 basically, as they can get it. But this is a boring way to ride seesaws, if you just sit here

balancing.

I guess it's not too boring. It's kind of exciting, trying to keep it balanced. But they can unbalance it

in order to rock back and forth in one of two ways. They can either push on the ground with their

feet.

So, Meagan, why don't you push on the ground? Okay, and that extra force produces another

torque, which causes Annie to rotate down. Now Annie can push down on the ground and cause

Meagan to rotate down. So, they're causing angular accelerations back and forth by exerting new

torques on it.

The other way they can unbalance this is by leaning.

So each one of them has a centre of gravity that's located somewhere sort of mid-body. But if they

lean, they can shift the location of their centre of gravity and therefore exactly where they're

exerting the forces on the seesaw board, and cause it again to experience a net torque so it

undergoes angular acceleration.

So, if you both lean towards Annie, what happens?

It goes down, Annie goes down, because basically the lever arm with which she's working gets

longer. And the one that Megan's working with gets shorter. So the torque is this way, toward me.

But now if we lean, everybody lean towards Megan.

Now the lever arms get longer and shorter in the opposite direction, and the net torque is toward

you. So, they can rock back and forth, so, this is how a seesaw works.

Okay, you guys can go at it.

All right, here we go.

Either way.

And this is what makes seesaw fun right, is all the adjustments of the torque so that you undergo

angular acceleration in opposite directions, back and forth.

>> This is so funny!

>> Seesaws are not the only structures in our world that need to balance. Mobile sculptures do as

well.

This mobile sculpture is entitled, happy hanging hardware. And I built it out of a torque wrench, a

ball peen hammer, and a metal file.

Amazingly enough, each of these components is rotationally inertial. You don't see any of them

undergoing angular acceleration, after all.

And that brings us to a question.

For all of the components of a mobile structure, to be rotationally inertial, how must those

components be arranged?

Each component of this mobile structure has its centre of gravity at or below the point at which that

component is supported. In effect, the pivot, about which that component could rotate.

This is actually a relatively complicated concept though. Because there are three components here

which aren't the individual tools.

First component, the simplest, is the file. That file has its centre of gravity at or below this support

point. Which is the loop of string going around it. That's the pivot about which the file can rotate.

And so, the file has its centre or gravity at or below that pivot. And therefore gravity produces no

torque on the file, it's rotationally inertial.

So far, so good.

The ball peen hammer isn't an object by itself, it's not the component by itself. Rather, the ball peen

hammer and the file together are the next component of this mobile. And that combined object,

ball peen hammer and file has its overall centre of gravity at or below its support point. This loop of

string.

And lastly, the torque wrench and everything below it has its combined centre of gravity at or below

this support point. The support point that is acting on the torque wrench.

So, each of these components, the file and the hammer and file and the wrench, hammer and file,

each of those components has its centre of gravity directly below its support. And therefore, gravity

and pulling down on the centre of gravity produces no torque on that component about its pivot. It

doesn't undergo any angular acceleration then due to gravity, it's balanced.

And so the file is balanced. The hammer and file are balanced. The wrench, hammer, and file are

balanced. The entire mobile then, is balanced, and it's all rotationally inertial.

So we see that objects that can rock or tip are only rotationally inertial if you balance them carefully.

Sometimes that's what you want, like with a mobile. Sometimes that's almost what you want, like

with a seesaw, where getting it perfectly balanced is interesting, but kind of unexciting in the long

run and you want to unbalance it a little bit to get some action happening.

We'll talk more about balance in the episode on bicycles, but for now, it's clear that in the context of

seesaws, balance and near balance are the name of the game.

Part 5.

Why do the riders' distances from the pivot affect the seesaw's responsiveness?

The answer to that question is that the farther the riders’ masses are from the pivot, the greater the

seesaw's overall rotational mass and the slower its angular accelerations.

Two riders can balance the seesaw in a variety of ways.

To begin with, they can go to the ends of the board and adjust their distances from the pivot

carefully until it balances. That is, until it experiences zero overall torque due to gravity. I mean I'm

pretty much there. Balanced seesaw.

But they can also come in close to the pivot and sit like this, with much smaller lever arms to work

with now, so that they're producing much smaller torques as individuals. But once again, those two

torques sum to zero. And there's zero overall torque due to gravity on this seesaw.

So, there are a variety of ways to balance the seesaw. And you might think that there's no

significant difference between those choices, but that's not true, there is a significant difference.

The farther these two riders sit from that central pivot, and therefore the axis of rotation, the

greater the seesaw's overall rotational mass. Now, rotational mass is not something completely

independent of ordinary mass. They're related, just as forces and torques are related. Every portion

of the seesaw's ordinary mass contributes to the seesaw's rotational mass. And the amount of

that contribution depends on where the portion of ordinary mass is. More specifically, on how far

that portion of ordinary mass is from the axis of rotation.

And that dependence on axis of rotation is a strong one. Small, modest changes in distance from

the axis of rotation can lead to large changes in the rotational mass contribution. The amount of

rotational mass contributed by a portion of ordinary mass is equal to the ordinary mass itself

times the square of the distance between that portion of ordinary mass and the axis of rotation.

So, taking a small portion here and doubling its distance from the axis of rotation doesn't just

double its contribution to the rotational mass, it quadruples it. That means that for the riders,

when they sit in close, and their distance from that central pivot and centre of rotation, axis of

rotation, is small, they contribute very little to its rotational mass, the overall rotational mass of the

seesaw and riders.

Even though these, these riders have large masses, they're too close to the axis of rotation to

contribute very strongly to its rotational mass. But if they go out like this, to a large distance, well,

then their contribution to rotational mass is huge. They might be only ten times as far away from

the pivot as before. From that axis of rotation. But an increase of distance by a factor of ten is an

increase in contribution to rotational mass of ten times ten, or ten squared, which is 100. So the

rotational mass contribution of these riders could easily be 100 times that of these riders.

It's a big effect. To see how big, I've made these two rods that look the same, and have the same

the masses. They contain the same materials actually. But the difference is that in one of these rods,

the mass is all in the middle, near my hand, under my hand, hidden from view. And in the other bar,

all of the mass is far from my hand, at the ends of the bar.

So, same mass, but in this case it's moved way out far from the centre of rotation, which will be here

in the middle bar. And the rotational mass of this bar is something like 30, 40 times that of this one.

Big difference. To see that difference, since you can't hold the bars, let's go get some help.

Annie and Megan are going to help me here with these two bars.

Now, these bars have the same masses and the same weights. So you could check that out. Just,

just compare the weights, do they feel the same?

>> Yeah, definitely even, uh-hm.

>> Yeah, definitely.

>> So, just by weighing them in your hands you can't tell the difference between these two bars. But

that doesn't mean they're identical. So the difference is going to be subtle, and this difference will

show up maybe when you begin to try to rock them back and forth.

So I want, Annie grab it in the middle of the bar, Megan same thing.

And I'm going to count to three, and on the number three, I want the two of you to rock it back and

forth as fast as you can. That is, make it undergo angular acceleration first one way and then the

other, back and forth as fast as you can.

>> Uh-hm.

>> 'Kay.

>> One. Two. Three.

>> This is really difficult.

>> So Annie's having no trouble here, and Meagan's really lagging behind. Must be weak today,

right? Forgot to eat your breakfast.

Okay, now swap bars.

>> Okay.

>> Thank you.

>> Now, I'll count again. One, two, three.

>> Oh.

>> Miraculous change.

>> What?

>> Something's different about these two bars. What do you think's different about the bars?

They have the same mass, what's different?

Megan?

>> Maybe the distribution of the mass within the bar?

>> So the distribution of the mass within the bar is different. Where is the mass in your bar, right

now?

>> In the centre.

>> So your bar has almost all of the mass in your hand.

>> Yeah.

>> As a result, the moment of inertia, or the rotational mass of this bar is very small.

>> Yeah.

>> It's very easy to make this bar undergo angular acceleration.

How about yours, Annie. Where do you think the mass is located?

>> I mean they must be at the end, right?

>> Yeah, so all the mass in this bar is at the ends where it contributes enormously to rotational mass.

So they have the same mass, it's just distributed differently. In Annie's bar it's at the ends, in

Megan's bar it's in the middle. And they behave totally differently when you try to rock them back

and forth.

>> Uh-hm.

>> Show us a little more time.

>> Sure.

>> I should make a face.

>> Yeah, it's, it's a pretty dramatic difference. Unfortunately you guys can't try it out.

>> But, but if you ever come by, test out these bars and see how different they are.

>> Okay.

>> Thanks.

>> Sure.

>> So you see, if you place an object's ordinary mass far from its axis of rotation, that object can

have a surprisingly large rotational mass. Now, the distance involved here is between ordinary mass

and the rotational axis. And you're often free to choose an object's rotational axis. If you do that,

and if you change your choice, you may well change the object's rotational mass. That ability to

change an object's rotational mass is why rotational motion is so complicated to calculate

quantitatively.

And that's a fact the keeps first year physics graduate students rather busy. It's hard work. I want to

give you a taste of the issues without trying to overwhelm you with them.

But look at this rod. This is the rod that's very hard to wobble back and forth like this because it has

an enormous rotational mass when you twist it back and forth about this axis. The one pointing

toward you through my hand or away from you through my hand. About that axis, gigantic

rotational mass.

But what about this axis in which I'm twisting it back and forth like a drill or a screwdriver? It's

easy. This direction has almost no rotational mass. That's because all the portions of ordinary mass

are very close to this spindle-like axis about which I'm twisting it.

So, this rod here, has two very different rotational masses, a huge one when you do this motion and

a tiny one when you do this motion.

Now this is, a, you know, fun and games rod. But something you're more familiar with is perhaps a

tennis racket. The tennis racket is a classic example of something that has three particularly

important rotational masses.

Its smallest rotational mass is for this rotation about the top bottom axis right now. This motion,

most of the mass is pretty close to that axis, the spindle about which I'm twisting it, and therefore it

has a relatively small rotational mass.

The next larger rotational mass is for this motion. Sometimes referred to as the frying pan motion,

when you're, you're flipping pancakes. So this is the intermediate rotational mass.

And the biggest rotational mass is for this rotation.

In between these motions, life is extremely complicated. And it's beyond the scope of this class as

something I don't like to deal with anymore. I've done it. Been there, done that, I'll leave it.

But these three distinct rotational masses, this small one, bigger one, biggest one, give the motion of

a tennis racket or anything shaped like a tennis racket, the rotational motion's quite complicated.

To make things even worse, these are all motions about the centre of mass. These are all rotations

in which the centre of mass stays put.

What if you shift the rotation, so that you don't care about the centre of mass of the tennis racket?

For example, when you're swinging a tennis racket about your shoulder. In that case, you're shifting

the mass of the tennis racket even farther from the centre of rotation, the axis about which you're

spinning it, and creating an even larger rotational mass for the tennis racket.

So the bottom line with all of this is rotational mass depends on your choice of axis of rotation.

We're finally ready for the question I asked you to think about in the introduction of this episode. To

remind you, that question asked if you and a child half your height lean out over a swimming pool

at the same angle and let go at the same moment, which of the two of you will hit the water first?

Despite a fair amount of rotational physics under our belts, that remains a challenging question.

So before I ask it, and leave you free to answer it, I want to give you a little more background. Get

you all prepped for this question.

First, what's the big picture issue? What is going to determine who hits first?

It's going to be angular acceleration. The one of you that undergoes the fastest angular acceleration

will develop the fastest angular velocity, will tip over the fastest and will hit the water first. So look

for big angular acceleration.

Second, what is the axis of rotation about which the two of you are going to be rotating?

It's not your centres of mass, it's going to be here at your feet.

That leaves two more issues. One is the cause of angular acceleration and the other is the

resistance to angular acceleration.

The cause is the neck torque on you. The resistance is your rotational mass.

And let's look at each one individually.

First Torque. The torque is due to gravity, and to make our lives simple, let's compare the torques

about this, about your feet, that's the axis rotation here for you and the child. Now, I've made life

very simple by using exactly the same board material. One is just half as long as the other, and this

makes, you know, this has all the physics in it, but none of the details. Life is easier.

So, you have twice the weight of the child, that's no surprise. And that weight effectively acts at

your centre of gravity, which is twice as far, it's right here in the middle. It’s twice as far from the

axis of rotation, as for the child. So, you're experiencing four times the gravitational torque of the

child. You have twice the weight acting at twice the lever arm. 2 times 2 is 4.

Right? 4 times the torque. That's the cause of angular acceleration.

How about the resistance to angular acceleration, the rotational mass?

Well, as compared to the child who has half the mass here, distributed around here with the centre