* Your assessment is very important for improving the work of artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Battle of Dunkirk

Invasion of Yugoslavia wikipedia , lookup

Operation Bodyguard wikipedia , lookup

Military history of Greece during World War II wikipedia , lookup

Naval history of World War II wikipedia , lookup

Battle of the Mediterranean wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Hürtgen Forest wikipedia , lookup

End of World War II in Europe wikipedia , lookup

Wehrmacht forces for the Ardennes Offensive wikipedia , lookup

Historiography of the Battle of France wikipedia , lookup

American Theater (World War II) wikipedia , lookup

Technology during World War II wikipedia , lookup

Écouché in the Second World War wikipedia , lookup

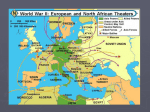

European theatre of World War II wikipedia , lookup

Battle of Dunkirk The Battle of Dunkirk (French: Bataille de Dunkerque) was a major battle during World War II which lasted from around May 26 to June 4, 1940. A large force of British and French soldiers were cut off in northern France by a German armoured advance to the Channel coast at Calais. Over 330,000 Allied troops caught in the pocket were subsequently evacuated by sea to England in Operation Dynamo. Background After the Phony War, the Battle of France began in earnest on May 10, 1940. The German Army Group A burst through the Ardennes region and advanced rapidly to the west, then turned north in the so-called "sickle cut". To the east, Army Group B invaded and subdued the Netherlands and advanced westward through Belgium. A British counterattack southward towards Arras on May 21 failed to sever the German spearhead, which had reached the coast the previous day, separating the British Expeditionary Force near Armentières and the Belgian army further to the north from the majority of French troops south of the German penetration. Next, the German armor swung north along the coast, threatening to capture the Channel ports and trap the British army and the adjacent French First Army before the soldiers could retreat to the relative safety of England. However, the unopposed German panzer divisions halted outside of Dunkirk on May 24. This order allowed preparation for a new southward advance against the remaining French forces. In addition, the terrain around Dunkirk was considered unsuitable for armor, so destruction of the British forces was initially assigned to the Luftwaffe and the German infantry organized in Army Group B. The Dunkirk Pocket On May 25, General Lord Gort, the commander of the BEF, decided to evacuate British forces. From May 25 to May 28, British troops retreated about 30 miles northwest into a pocket along the Franco-Belgian border extending from Dunkirk on the coast to the Belgian town of Poperinge. Meanwhile, the Belgian army surrendered, followed by most of the French 1st Army on May 29. Starting on May 27, Operation Dynamo began the evacuation of Allied troops from the Dunkirk area. The German Panzer divisions were ordered to resume their advance the same day, but improved British defenses halted their offensive, although the remaining Allied forces were compressed into a 5 km wide coastal strip from De Panne through Bray-Dunes to Dunkirk by May 31. A total of five nations took part in the successful evacuation from Dunkirk - Britain, France, Belgium, Netherlands and Poland. Aftermath The successful evacuation of troops from Dunkirk ended the first phase in the Battle of France. It provided a great boost to British morale, but left the French to stand alone against a renewed German assault southwards. German troops entered Paris on June 14 and accepted the unconditional surrender of France on June 22. Many soldiers lost their backpacks and shoes while they were treading through the mud. It has been suggested that the German fighters may have put Quicksand on the beach[citation needed]. What if? The battle of Dunkirk poses one of the great "what-ifs" of World War II, which has attracted speculation from many military historians. If Hitler had not ordered the German panzer divisions to halt from 24 May to 26 May, but instead ordered an all-out attack on Dunkirk, the retreating Allies could have possibly been cut off from the sea and destroyed. If the whole of the British Expeditionary Force had been captured or killed at Dunkirk, morale in Britain could have possibly sunk so low as to have toppled the government and replaced it with one more disposed to making an accommodation with Nazi Germany, like the Vichy regime in France. Without the need to oppose the British in the Atlantic and North Africa — or even with the assistance of a Quisling government in Britain — perhaps the troops and resources thus freed would have been enough to wholly defeat the Soviet Union in 1941 and led to German conquest of the whole of Europe and Asia. On the other hand, the panzer divisions were stopped for repairs and resupply, and to allow the rest of the army to catch up. Had they pushed forward recklessly, they could have outrun their supply lines and become vulnerable to being cut off themselves. Even if the British Expeditionary Force had been cut off and destroyed, few in Britain wanted to collaborate with the Nazis — Churchill had become Prime Minister after the fall of the Chamberlain government on May 10, 1940 precisely because his uncompromising belligerence reflected the mood of the nation. Later fighting at Dunkirk The city of Dunkirk was besieged in September 1944 by units of the Second Canadian Division; German units withstood the siege, and as the First Canadian Army moved north into Belgium, the city was "masked" and left to wither on the vine. The German garrison in Dunkirk held out until May 1945, denying the Allies the use of the port facilities. Operation Barbarossa At 5:30 a.m. on 22 June 1941, the German ambassador met with Molotov to announce a declaration of war on the basis of gross and repeated violations of the Russo-German Pact. The two largest and most powerful armies ever assembled confronted each other along a 3,000 kilometer line from the Barents Sea to the Black Sea. While the Russians were well aware of German preparations, and were tipped off to the impending invasion by both their own intelligence, as well foreign sources, the Germans achieved total surprise. The Germans employed three army groups (North commanded by Field Marshal Wilhelm von Leeb, Center commanded by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock, and South commanded by Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt), and planned to destroy all Soviet resistance in swift advances on Leningrad, Moscow, and Kiev. Hitler threw 183 divisions into the assault, while the Nazis faced 170 divisions, which represented 54 percent of the Red Army's total strength. Subsequently, the German armies were to occupy a line reaching from Archangel on the White Sea to Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea. The German invasion represented a great gamble. Germany was already at war with Great Britain and occupied much of Europe. Russia possessed an inhospitable climate, a vast area, and tremendous manpower reserves. Hitler himself expressed ambiguous feelings on Operation Barbarossa, the German codeword for the Russian invasion. To one of his generals he said, "We have only to kick in the door and the whole rotten structure will come crashing down," but shortly later he also stated, "At the beginning of each campaign one pushes a door into a dark, unseen room. One can never know what is hiding inside." Coupled with the element of surprise, the Germans possessed better training, more extensive experience, and were able to obtain decisive superiority at the points selected for attack. The Russians had large amounts of obsolete equipment, were poorly deployed to meet the attack, and lacked defensive positions. As a result, the Russian frontier was quickly overrun and the Germans achieved penetrations in many places. By 16 July, 1941, the Germans had captured Smolensk, which was less than 250 miles from Moscow, and Army Group Center alone had captured about 600,000 men and 5,000 tanks. The Soviet attitude can perhaps best be summarized by Molotov, who said, "Surely, we have not deserved that," when notified by the German ambassador, Friedrich von Schulenberg, that Germany had been forced to take 'counter-measures' in light of Russian military build-up on the border. Stalin is said to have had a "nervous collapse" when told of the invasion and did not speak for 11 days. On 3 July, Stalin finally made a radio address to the Russian people, which contained several elements of Russian strategy. He evoked a sense of nationalism in his opening words: "Comrades, citizens, brothers, and sisters, fighters of our Army and Navy." He declared, "We must immediately put our whole production to war footing. In all occupied territories partisan units must be formed. . ." Stalin continued to say that losses had been severe and although the Red Army was putting up a heroic resistance, the country was in moral danger, but Stalin reminded them of the fates of Napoleon and Kaiser Wilhelm. Stalin justified the Russo-German Pact on the grounds that it gave the country the time to build its defenses. Stalin also announced a "scorched earth" policy to deny the Germans "a single engine, or a single railway truck, and not a pound of bread nor a pint of oil." He also announced with "a feeling of gratitude" the offers of assistance from Britain and the United States. So desperate did the Russians become during the early stages of Operation Barbarossa to gain any support and assistance, they even signed an agreement with the Polish government-in-exile, with whom they were not in speaking terms since the Russian occupation of Eastern Poland in September, 1939. By the end of July the Germans controlled an area of the Soviet territory more than twice the size of France. The Battle of Britain Immediately after the defeat of France, Adolf Hitler ordered his generals to organize the invasion of Britain. The invasion plan was given the code name Sealion. The objective was to land 160,000 German soldiers along a forty-mile coastal stretch of south-east England. Within a few weeks the Germans had assembled a large armada of vessels, including 2,000 barges in German, Belgian and French harbours. However, Hitler's generals were very worried about the damage that the Royal Air Force could inflict on the German Army during the invasion. Hitler therefore agreed to their request that the invasion should be postponed until the British airforce had been destroyed. By the start of what became known as the Battle of Britain the Luftwaffe had 2,800 aircraft stationed in France, Belgium, Holland and Norway. This force outnumbered the RAF four to one. However, the British had the advantage of being closer to their airfields. German fighters could only stay over England for about half an hour before flying back to their home bases. The RAF also had the benefits of an effective early warning radar system and the intelligence information provided by Ultra. The German pilots had more combat experience than the British and probably had the best fighter plane in the Messerschmitt Bf109. They also had the impressive Messerschmitt 110 and Junkers Stuka. The commander of Fighter Command, Hugh Dowding, relied on the Hawker Hurricane and the Supermarine Spitfire. On the 12th August, 1940, the German airforce began its mass bomber attacks on British radar stations, aircraft factories and fighter airfields. During these raids radar stations and airfields were badly damaged and twenty-two RAF planes were destroyed. This attack was followed by daily raids on Britain. As a result of the effective range of the Luftwaffe, the battle was mainly fought over southern England. This area was protected by Fighter Command No. 11 under Keith Park and Fighter Command No. 12 led by Trafford Leigh-Mallory. They also but received support from the squadrons based in the eastern counties. Between 1st and 18th August the RAF lost 208 fighters and 106 pilots. The second half of the month saw even heavier losses and wastage now outstripped the production of new aircraft and the training of pilots to fly them. Those British pilots that did survive suffered from combat fatigue. During the Battle of Britain Trafford Leigh-Mallory came into conflict with Keith Park, the commander of No. 11 Fighter Group. Park, who was responsible for the main approaches south-east of London, took the brunt of the early attacks by the Luftwaffe. Park complained that No. 12 Fighter Group should have done more to protect the air bases in his area instead of going off hunting for German planes to shoot down. Leigh-Mallory obtained support from Vice Marshal William Sholto Douglas, assistant chief of air staff. He was critical of the tactics being used by Keith Park and Hugh Dowding, head of Fighter Command. He took the view that RAF fighters should be sent out to meet the German planes before they reached Britain. Park and Dowding rejected this strategy as being too dangerous and argued it would increase the number of pilots being killed. The climax of the Battle of Britain came on the 30th-31st August, 1940. The British lost 50 aircraft compared to the Germany's 41. The RAF were close to defeat but Adolf Hitler then changed his tactics and ordered the Luftwaffe to switch its attack from British airfields, factories and docks to civilian targets. This decision was the result of a bombing attack on Berlin that had been ordered by Charles Portal, the new head of Bomber Command. The Blitz brought an end to the Battle of Britain. During the conflict the Royal Air Force lost 792 planes and the Luftwaffe 1,389. There were 2,353 men from Great Britain and 574 from overseas who were members of the air crews that took part in the Battle of Britain. An estimated 544 were killed and a further 791 lost their lives in the course of their duties before the war came to an end. The Battle for Stalingrad After the narrow failure of Hitler's invasion of Russia in 1941 the German Army no longer had the strength and resources for a renewed offensive of that year's scale, but Hitler was unwilling to stay on the defensive and consolidate his gains. So he searched for an offensive solution that with limited means might promise more than a limited result. No longer having the strength to attack along the whole front, he concentrated on. the southern part, with the aim of capturing the Caucasus oil which each side needed if it was to maintain its full mobility. If he could gain that oil, he might subsequently turn north onto the rear of the thus immobilised Russian armies covering Moscow, or even strike at Russia's new warindustries that had been established in the Urals. The 1942 offensive was, however, a greater gamble than thatof the previous year because, if it were to be checked, the long flank of this southerly drive would be exposed to a counterstroke anywhere along its thousand-mile stretch. Initially, the German Blitzkrieg technique scored again - its fifth distinct and tremendous success since the conquest of Poland in 1939. A swift break-through was made on the Kursk-Kharkov sector, and then General Bwald von Kleist's 1st Panzer Army swept like a torrent along the corridor between the Don and the Donetz rivers. Surging across the Lower Don, gateway to the Caucasus, it gained the more westerly oilfields around Maikop in six weeks. The Russians' resistance had crumbled badly under the impact of the Blitzkrieg, and Kleist had met little opposition in the later stages of his drive. This was Russia's weakest hour. Only an instalment of her freshly raised armies was yet ready for action, and even that was very short of equipment, especially artillery. Fortunately for Russia, Hitler split his effort between the Caucasus and Stalingrad on the Volga, gateway to the north and the Urals. Moreover when the first attacks on Stalingrad, by Paulus's 6th Army, were checked in mid-July, although narrowly checked, Hitler increasingly drained his forces in the Caucasus to reinforce the divergent attack on Stalingrad. This was by name, 'the city of Stalin' so Hitler could not bear to be defied by it - and became obsessed by it. He wore down his forces in the prolonged effort to achieve its capture, losing sight of his initial prime aim, the vital oil supplies of the Caucasus. When Kleist drove on from Maikop towards the main oilfields, his army met increasing resistance from local troops, fighting, now to defend their homes, while itself being depleted in favour of Paulus' bid to capture Stalingrad. At Stalingrad the Russians' resistance hardened with repeated hammering, while the directnesa, and consequent obviousness, of the German attacks there simplified the Russian Higher Command's problem in meeting the threat. The Germans' concentration at Stalingrad also, and increasingly, drained reserves from their flank-cover, which was already strained by having to stretch so far, nearly 400 miles from Voronezh along the Don to the point where it nears the Volga at Stalingrad, and as far again from there to the Terek in the Caucasus. A realisation of the risks led the German General Staff to tell Hitler in August that it would be impossible to hold the line of the Don as a defensive flank, during the winter, but the warning was ignored by him in his obsession with capturing Stalingrad. The Russian defenders' position there came to look more and more imperilled, even desperate, as the circle contracted and the Germans came closer to the heart of the city. The most critical moment was on October 14th. The Russians now had their backs so close to the Volga that they had no room to practise shock-absorbing tactics, and sell ground to gain time. But beneath the surface, basic factors were working in their favour. The German attackers' morale was being sapped by their heavy losses, and a growing sense of frustration, so that they were becoming ripe for the counter-offensive that the Russians were preparing to launch, with new armies, against the German flanks which were held by Rumanian and other allied troops of poorer quality. This counter-offensive was launched on November 19th. Wedges were driven into the flanks at several places, so as to isolate Paulus's 6th Army, By the 23rd the encirclement was complete, more than quarter of a million German and allied troops being thus cut off. Hitler would permit no withdrawal, and relieving attempts in December were repulsed. Even then Hitler was reluctant to permit the 6th Army to try to break-out westward before it was too late, and air supply had proved inadequate. The end came, the end of a battle of over six months' duration, with the surrender of Paulus and the bulk of what remained of his exhausted and near-starving army on January 31st, although an isolated remnant in a northerly pocket held out for two days longer. Pearl Harbor Japanese military leaders recognized American naval strength as the chief deterrent to war with the United States. Early in 1941, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander of the Japanese Combined Fleet, had initiated planning for a surprise attack on the United States Pacific Fleet at the beginning of any hostilities that the Japanese might undertake. The assumption was that before the United States could recover from a surprise blow, the Japanese would be able to seize all their objectives in the Far East, and could then hold out indefinitely. By September 1941 the Japanese had practically completed secret plans for a huge assault against Malaya, the Philippines, and the Netherlands East Indies, to be coordinated with a crushing blow on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Island of Oahu. Early in November Vice Admiral Chuichi Nagumo was named commander of the Pearl Harbor Striking Force, which rendezvoused secretly in the Kuriles. The force of some 30 ships included six aircraft carriers with about 430 planes, of which approximately 360 took part in the subsequent attack. At the same time, a Japanese Advance Expeditionary Force of some 20 submarines was assembled at Kure naval base on the west coast of Honshu to cooperate in the attack. Submarines of the Advance Expeditionary Force began their eastward movement across the Pacific in mid-November, refueled and resupplied in the Marshalls, and arrived near Oahu about December 5 (Hawaiian time). On the night of December 6-7 five midget (two-man) submarines that had been carried "piggy-back" on large submarines cast off and began converging on Pearl Harbor. Nagumo's task force sailed from the Kuriles on 26 November and arrived, undetected by the Americans, at a point about 200 miles north of Oahu at 0600 hours (Hawaiian time) on December 7, 1941. Beginning at 0600 and ending at 0715, a total of some 360 planes were launched in three waves. These planes rendezvoused to the south and then flew toward Oahu for coordinated attacks. In Pearl Harbor were 96 vessels, the bulk of the United States Pacific Fleet. Eight battleships of the Fleet were there, but the aircraft carriers were all at sea. The Commander in Chief of the Pacific Fleet (CINCPAC) was Admiral Husband E. Kimmel. Army forces in Hawaii, including the 24th and 25th Infantry Divisions, were under the command of Lt. Gen. Walter C. Short, Commanding General of the Hawaiian Department. On the several airfields were a total of about 390 Navy and Army planes of all types, of which less than 300 were available for combat or observation purposes. The Japanese air attack on Pearl Harbor and on the airfields of Oahu began at 0755 on December 7, 1941 and ended shortly before 1000. Quickly recovering from the initial shock of surprise, the Americans fought back vigorously with antiaircraft fire. Devastation of the airfields was so quick and thorough that only a few American planes were able to participate in the counterattack. The Japanese were successful in accomplishing their principal mission, which was to cripple the Pacific Fleet. They sunk three battleships, caused another to capsize, and severely damaged the other four. All together the Japanese sank or severely damaged 18 ships, including the 8 battleships, three light cruisers, and three destroyers. On the airfields the Japanese destroyed 161 American planes (Army 74, Navy 87) and seriously damaged 102 (Army 71, Navy 31). The Navy and Marine Corps suffered a total of 2,896 casualties of which 2,117 were deaths (Navy 2,008, Marines 109) and 779 wounded (Navy 710, Marines 69). The Army (as of midnight, 10 December) lost 228 killed or died of wounds, 113 seriously wounded and 346 slightly wounded. In addition, at least 57 civilians were killed and nearly as many seriously injured. The Japanese lost 29 planes over Oahu, one large submarine (on 10 December), and all five of the midget submarines. Their personnel losses (according to Japanese sources) were 55 airmen, nine crewmen on the midget submarines, and an unknown number on the large submarines. The Japanese carrier task force sailed away undetected and unscathed. On December 8, 1941, within less than an hour after a stirring, six-minute address by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Congress voted, with only one member dissenting, that a state of war existed between the United States and Japan, and empowered the President to wage war with all the resources of the country. Four days after Pearl Harbor, December 11, 1941, Germany and Italy declared war on the United States. Congress, this time without a dissenting vote, immediately recognized the existence of a state of war with Germany and Italy, and also rescinded an article of the Selective Service Act prohibiting the use of American armed forces beyond the Western Hemisphere. The Battle of El Alamein The Battle of El Alamein, fought in the deserts of North Africa, is seen as one of the decisive victories of World War Two. The Battle of El Alamein was primarily fought between two of the outstanding commanders of World War Two, Montgomery, who succeeded the dismissed Auchinleck, and Rommel. The Allied victory at El Alamein lead to the retreat of the Afrika Korps and the German surrender in North Africa in May 1943. El Alamein is 150 miles west of Cairo. By the summer of 1942, the Allies were in trouble throughout Europe. The attack on Russia - Operation Barbarossa - had pushed the Russians back; U-boats were having a major effect on Britain in the Battle of the Atlantic and western Europe seemed to be fully in the control of the Germans. Hence the war in the desert of North Africa was pivotal. If the Afrika Korps got to the Suez Canal, the ability of the Allies to supply themselves would be severely dented. The only alternate supply route would be via South Africa - which was not only longer but a lot more dangerous due to the vagaries of the weather. The psychological blow of losing the Suez and losing in North Africa would have been incalculable - especially as this would have given Germany near enough free access to the oil in the Middle East. El Alamein was a last stand for the Allies in North Africa. To the north of this apparently unremarkable town was the Mediterranean Sea and to the south was the Qattara Depression. El Alamein was a bottleneck that ensures that Rommel could not use his favoured form of attack - sweeping into the enemy from the rear. Rommel was a well respected general in the ranks of the Allies. The Allied commander at the time, Claude Auchinleck - did not command the same respect among his own men. Auchinleck had to send a memo to all his senior officers that ordered them to do all in their power to correct this: In August 1942, Winston Churchill was desperate for a victory as he believed that morale was being sapped in Britain. Churchill, despite his status, faced the prospect of a vote of no confidence in the House of Commons if there was no forthcoming victory anywhere. Churchill grasped the bull by the horns./ he dismissed Auchinleck and replaced him with Bernard Montgomery. The men in the Allied forces respected ‘Monty’. He was described as "as quick as a ferret and about as likeable." Montgomery put a great deal of emphasis on organisation and morale. He spoke to his troops and attempted to restore confidence in them. But above all else, he knew that he needed to hold El Alamein anyway possible. To cope with Montgomery’s attack, the Germans had 110,000 men and 500 tanks. A number of these tanks were poor Italian tanks and could not match the new Sherman’s. The Germans were also short of fuel. The Allies had more than 200,000 men and more than 1000 tanks. They were also armed with a six-pound artillery gun which was highly effective up to 1500 metres. Between the two armies was the ‘Devil’s Garden’. This was a mine field laid by the Germans which was 5 miles wide and littered with a huge number of anti-tank and anti-personnel mines. Going through such a defence would prove to be a nightmare for the Allies. To throw Rommel off the scent, Montgomery launched ‘Operation Bertram’. This plan was to convince Rommel that the full-might of the Eighth Army would be used in the south. Dummy tanks were erected in the region. A dummy pipeline was also built - slowly, so as to convince Rommel that the Allies were in no hurry to attack the Afrika Korps. ‘Monty’s army in the north also had to ‘disappear’. Tanks were covered so as to appear as non-threatening lorries. Bertram worked as Rommel became convinced that the attack would be in the south. The start of the Allied attack on Rommel was code-named "Operation Lightfoot". There was a reason for this. A diversionary attack in the south was meant to take in 50% of Rommel’s forces. The main attack in the north was to last - according to Montgomery - just one night. The infantry had to attack first. Many of the anti-tank mines would not be tripped by soldiers running over them - they were too light (hence the code-name). As the infantry attacked, engineers had to clear a path for the tanks coming up in the rear. Each stretch of land cleared of mines was to be 24 feet - just enough to get a tank through in single file. The engineers had to clear a five mile section through the ‘Devil’s Garden’. It was an awesome task and one that essentially failed. ‘Monty’ had a simple message for his troops on the eve of the battle: The attack on Rommel’s lines started with over 800 artillery guns firing at the German lines. Legend has it that the noise was so great that the ears of the gunners bled. As the shells pounded the German lines, the infantry attacked. The engineers set about clearing mines. Their task was very dangerous as one mine was inter-connected with others via wires and if one mines was set off, many others could be. The stretch of cleared land for the tanks proved to be Montgomery’s Achilles heel. Just one non-moving tank could hold up all the tanks that were behind it. The ensuing traffic jams made the tanks easy targets for the German gunners using the feared 88 artillery gun. The plan to get the tanks through in one night failed. The infantry had also not got as far as Montgomery had planned. They had to dig in. The second night of the attack was also unsuccessful. ‘Monty’ blamed his chief of tanks, Lumsden. He was given a simple ultimatum - move forward - or be replaced by someone more energetic. But the rate of attrition of the Allied forces was taking its toll. Operation Lightfoot was called off and Montgomery, not Lumsden, withdrew his tanks. When he received the news, Churchill was furious as he believed that Montgomery was letting victory go. However, Rommel and the Afrika Korps had also been suffering. He only had 300 tanks left to the Allies 900+. ‘Monty’ next planned to make a move to the Mediterranean. Australian units attacked the Germans by the Mediterranean and Rommel had to move his tanks north to cover this. The Australians took many casualties but their attack was to change the course of the battle. Rommel became convinced that the main thrust of Montgomery’s attack would be near the Mediterranean and he moved a large amount of his Afrika Korps there. The Australians fought with ferocity - even Rommel commented on the "rivers of blood" in the region. However, the Australians had given Montgomery room to manoeuvre. He launched ‘Operation Supercharge’. This was a British and New Zealander infantry attack made south of where the Australians were fighting. Rommel was taken by surprise. 123 tanks of the 9 th Armoured Brigade attacked the German lines. But a sandstorm once again saved Rommel. Many of the tanks got lost and they were easy for the German 88 gunners to pick off. 75% of the 9th Brigade was lost. But the overwhelming number of Allied tanks meant that more arrived to help out and it was these tanks that tipped the balance. Rommel put tank against tank - but his men were hopelessly outnumbered. By November 2nd 1942, Rommel knew that he was beaten. Hitler ordered the Afrika Korps to fight to the last but Rommel refused to carry out this order. On November 4th, Rommel started his retreat. 25,000 Germans and Italians had been killed or wounded in the battle and 13,000 Allied troops in the Eighth Army. D-Day/Normandy Invasion In November, 1943, Joseph Stalin, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt met together in Teheran, Iran, to discuss military strategy and post-war Europe. Ever since the Soviet Union had entered the war, Stalin had been demanding that the Allies open-up a second front in Europe. Churchill and Roosevelt argued that any attempt to land troops in Western Europe would result in heavy casualties. Until the Soviet's victory at Stalingrad in January, 1943, Stalin had feared that without a second front, Germany would defeat them. Stalin, who always favoured in offensive strategy, believed that there were political, as well as military reasons for the Allies' failure to open up a second front in Europe. Stalin was still highly suspicious of Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt and was worried about them signing a peace agreement with Adolf Hitler. The foreign policies of the capitalist countries since the October Revolution had convinced Stalin that their main objective was the destruction of the communist system in the Soviet Union. Stalin was fully aware that if Britain and the USA withdrew from the war, the Red Army would have great difficulty in dealing with Germany on its own. At Teheran, Joseph Stalin reminded Churchill and Roosevelt of a previous promise of landing troops in Western Europe in 1942. Later they postponed it to the spring of 1943. Stalin complained that it was now November and there was still no sign of an allied invasion of France. After lengthy discussions it was agreed that the Allies would mount a major offensive in the spring of 1944. General Dwight Eisenhower was put in charge of what became known as Operation Overlord. Eisenhower had the task of organizing around a million combat troops and two million men involved in providing support services. The plan, drawn up by George Marshall, Dwight Eisenhower, Bernard Montgomery, Omar Bradley, Bertram Ramsay, Walter Bedell-Smith, Arthur Tedder and Trafford Leigh-Mallory, involved assaults on five beaches west of the Orne River near Caen (codenamed Sword, Juno, Gold, Omaha and Utah) by the British 2nd Army and the American 1st Army. Follow-up forces included the Canadian 1st Army and the American 3rd Army under Lt. General George Patton. Juno was assigned to the Canadian Army. Canada contributed 110 ships to the invading force, 14,000 troops, including paratroopers, and 15 RCAF squadrons of fighters and fighter-bombers. It is estimated that Canada contributed about 10 percent of the D-Day invading force. The invasion was preceded by a massive aerial bombardment of German communications. This resulted in the destruction of virtually every bridge over the Seine. On 6th June, 1944, 2,727 ships sailed to the Normandy coast and on the first day landed 156,000 men on a front of thirty miles. It was the largest and most powerful armada that has ever sailed. The Allied invasion was faced by 50 divisions of the German Army under General Erwin Rommel. At Omaha, steep cliffs favoured the defenders and the US Army suffered 2,500 casualties. The Allies also sent in three airborne divisions, two American and one British, to prepare for the main assault by taking certain strategic points and by disrupting German communications. Of the 23,000 airborne troops, 15,500 were Americans and of these, 6,000 were killed or seriously wounded. Over the next couple of days 156,215 troops were landed from sea and air in Normandy, at a cost of some 10,300 casualties. The Battle of the Bulge The Battle of the Bulge which lasted from December 16, 1944 to January 28, 1945 was the largest land battle of World War II in which the United States participated. More than a million men fought in this battle including some 600,000 Germans, 500,000 Americans, and 55,000 British. The German military force consisted of two Armies with ten corps(equal to 29 divisions). While the American military force consisted of a total of three armies with six corps(equal to 31 divisions). At the conclusion of the battle the casualties were as follows: 81,000 U.S. with 19,000 killed, 1400 British with 200 killed, and 100,000 Germans killed, wounded or captured. In late 1944 Germany was clearly losing the war. The Russian Red Army was steadily closing in on the Eastern front while German cities were being devastated by intense American bombing. The Italian peninsula had been captured and liberated, and the Allied armies were advancing rapidly through France and the Low Countries. Hitler knew the end was near if something couldn't be done to slow the Allied advance. He soon came up with a plan to do this. This plan was code named Wacht am Rhein with the strategy of driving on Antwerp while encircling the Allied armies west of the Meuse River. Hitler thought the name of the plan would confuse the Allies into believing it was a defensive operation. The Ardennes was selected as the location for the offensive because the area provided enough cover for a massive buildup of troops and because it was the location where in 1940 Hitler had initiated a surprise attack on France. Hitler believed that by retaking Antwerp the Allies would become irritated with each other and would lead to disputes between the members of the Allies. He believed the bond between the Allies was unstable and could easily be diminished. In doing so Hitler would be able to buy some much needed time to work on secret weapons and build up troops. During the months between October and November the Watch on the Rhine was Renamed Autumn Mist. Hitler changed the name after several of his military commanders tried to convince him to change the plans. The commanders in charge of the offensive, von Runstedt(Commander of the West), Field Marshall Model(tactical commander), Josef"Sepp"Dietrich (leader of the Sixth Panzer Army), and Hoss von Manteuffel (commander of Fifth Panzer Unit) all were skeptical about Hitler's plan. They felt that taking Antwerp was something that just could not be accomplished by the German army at the time. Field Marshall Model was quoted as saying "This plan hasn't got a damned leg to stand on". Hitler was presented with a new smaller plan which changed the objective to only launching a small attack to weaken the Allied forces in the area rather than launching an all out attack to retake Antwerp. His general's pleaded with him to change the plans but Hitler refused. Many people think that Hitler was unstable by this time in the war. He would not listen to his advising commanders. An assassination attempt had been made on his life and this caused him to trust almost no one. Hitler's plan to retake Antwerp was irrational in that the German's would have no air support and the supplies that they would need were lacking. Also what Hitler expected to result from retaking Antwerp was irrational. The bond between the Allied powers might not have been strong, but they were definitely unified in one goaldestroying the German regime. At 5:30 A.M. on December 6, 1944 eight German armored divisions and thirteen German infantry divisions launched an all out attack on five divisions of the United States 1st Army. At least 657, light, medium, and heavy guns and howitzers and 340 multiple-rocket launchers were fired on American positions. Between the 5th and 6th Panzer armies which equaled eleven divisions they broke into the Ardennes through the Loshein Gap against the American divisions protecting the region. The 6th Panzer Army then headed North while the Fifth Panzer Army went south. Sixth Panzer army attacked the two southern divisions of U. S. V Corps at Elsborn Ridge, but accomplished little. At the same time the 5th Panzer Army was attacking the U. S. VIII Corps some 100 miles to the south. This corps was one of the greenest in Europe at the time and their lack of experience was exploited by the Germans. They were quickly surrounded and there were mass surrenders. On December 17 American 7th Armored divisions engaged Dietrich's Sixth Panzer Army at Saint Vith. Saint Vith was a major road that led to the Meuse River and to Antwerp. The American division was successful in halting the German advance and this caused the Germans to take a path that was out of the way. This slowed the Germans down and altered the timing of the German attack plan. The same day some Americans were taken prisoner at Baugnez and were shot by Colonel Peiper's unit while on a road headed for Malmeddy. Of the 140 men taken prisoner 86 were shot and 43 managed to survive to tell the story of what had happened. Rumors of this event spread quickly through the American divisions causing the Americans to fight much harder and with more resolve. Bastogne was a strategic position which both the Germans and Americans wanted to occupy. This lead to a race between the American 101st Airborne divisions and the Germans. The Americans managed to get there first and occupy the city. The Germans were not far behind and quickly surrounded and laid siege to the city. This city was an important strategic location for the Allies because this city could be used as a base to launch a counteroffensive. On December 22 German officers under the flag of truce delivered a message from General der Panzertruppe von Luttwitz Commander of XLVII Panzerhops, demanding the surrender of Bastogne. After receiving the message Brigadier General Mcauliffe exclaimed "Aw, nuts" which was his official reply to the request for surrender. This message was delivered by Joseph Harper to the Germans. He told the Germans it meant they could all go to Hell. With that they parted and the siege continued. Because the Americans were surrounded the only way they could get supplies was by air drops. However because it was the winter and the weather was bad for a long time planes could not fly. The Americans had to survive the best they could until the weather finally cleared up. The Americans at Bastogne were relieved when the VII Corps moved down and enlarged the U. S. line. This allowed Patton's Third Army to counterattack the Germans surrounding Bastogne. The Third Army was then able to push the Germans past the border of Bastogne. Bastogne was not out of danger however, and on December 29 troops from the 101st Airborne division left Bastogne to fight the Germans. At this time the weather had cleared up which allowed Allied air support for the first time. At the same time General Hodges 2nd Armored divisions repelled the 2nd Panzer division short of the Meuse River at Celles. The Allies launched a counteroffensive two days before the New Year. This counteroffensive involved the U.S. Third Army striking to the North while the U.S. First Army pushed to the South. They were supposed to meet at the village of Houffalize to trap all German force. The Germans did not go easily however and the Americans had a rough time. Day after day, soldiers wallowed through the snow. Newspapers were put under clothes as added insulation. On January first, Hitler launched a plan he called "The Great Blow." The goal of this plan was to eliminate Allied air power. At 8:00 A.M. German fighter airplanes swarmed over Belgium, Holland, and northern France. For more than two hours Allied airfields were bombarded. By 10:00 A.M. 206 aircraft and many bases layed in ruin. Hitler's plan had a great deal of damage to Allied aircraft. However, the price he paid for this was devastating. The German Luftwaffe lost 300 planes and 253 trained pilots. On January 8, Hitler ordered his troops to withdraw from the tip of the Bulge. This indicated that he had realized his offensive had failed. By January 16, the Third and First Army had joined at Houffalize. The Allies now controlled the original front. On January 23, Saint Vith was retaken. Finally, on January 28 the Battle of the Bulge was officially over. The Battle of the Bulge was very costly in terms of both men and equipment. Hitler's last ditch attempt to bring Germany back into winning the war had failed. During this battle the Germans had expended the majority of there Air power and men. The Allies however had plenty of men and equipment left. With few forces left to defend "The Reich" the Germans could not prolong the inevitable. Germanys final defeat was only months away. The Battle of Midway In the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbour on Dec 7th 1941 the Americans were determined to take revenge yet although the attack had missed their carriers and the vital fuel reserves had been left untouched, it would be some time before the American fleet could openly challenge the Japanese. On 18th April 1942 the Americans hit back with a raid of Mitchell B25 bombers bombing Tokyo and several other Japanese cities after taking off from US carriers. The blow had tremendous on the Japanese who believed their homeland safe from attack. Admiral Yamamoto apologised to the Emperor and vowed to destroy the US fleet. The Japanese plan was to lure the Americans into a trap by attacking the small island of Midway 1,136 miles west of Pearl Harbour. Without Midway US long range patrol planes could not effectively screen Pearl Harbour and it would be open to surprise attack once again making it unusable. The attack would start with a diversionary attack on the Aleutian Island forcing US ships to investigate while an invasion force under Admiral Nagumo would attack the island. Midway was not the main objective, and while the invasion would draw out the US fleet,the main force(including 4 carriers) Yamamoto would be waiting 300 miles away to trap and destroy the Americans. A huge fleet of over 200 ships(including 11 battleships and 8 carriers) was gathered and divided into 8 task forces, against this the Americans had 3 aircraft carriers 3 cruisers and 14 destroyers. The Japanese were so confident they even arranged for their mail to be sent to Midway. The attack was planned for June 7th but the Japanese were in for a few surprises. Despite efforts to confuse them the Americans knew what was going on. The Japanese codes had been cracked and after leaking a message saying that Midways freshwater plant was broken the Americans new that Midway was the target. Admiral Nimitz had only three carriers, with others either damaged or too far away. The Americans set a trap of their own, with the Carrier Yorktown waiting 200 miles north east of Midway, the Americans then set about reinforcing Midway with aircraft, anti aircraft guns, barbed wire and fast torpedo boats. As the Japanese set out for Midway they changed their codes but the damage had been done, by then the Americans even knew how many ships and who captains were, and what course the Japanese had set. The battle got underway with a series of air attacks by US planes based on Midway with the Japanese attacking the Island with their carrier based force. Neither side did much serious damage as the Japanese fleet proved too well defended and the American crews too inexperienced. During this aerial boxing match the US spotter planes, Catalina's proved vital, with their courageous crews performing many acts of bravery to shadow the Japanese fleet and provide vital intelligence. During the height of these attacks a Japanese spotter plane sighted 10 enemy ships only 200 miles from the Japanese task force, the Japanese Admiral realised that with his aircraft reloading with bombs ready for another attack on Midway, he was very vulnerable and needed to reload with torpedoes quickly, then the message came in that the ships contained no carriers so the Japanese continued loading bombs a fatal mistake. Within 20 minutes the report came in that the American ships did have a carrier with them ! Again Nagumo changed the loading of the planes and started to retire to allow his planes to rearm, his fighters were just coming in to land being short on fuel, as the last plane landed the American air attack began just as the Japanese were most vulnerable. The first attacks were met by the zeros on patrol but as they landed to refuel the main American attack struck the now defenceless carriers. In six minutes the Akagi, Nagumos flagship carrier was burning, the Kaga was next followed by the Soryu. When Yamamoto received the news he had no choice but to sail on in the now thickening fog. The last Japanese carrier counterattacked and turned the Yorktown into a crippled wreck which slogged on until finally sunk by a submarine on 6th June. the Americans gathered their remaining bombers and attacked again setting the last carrier the Hiryu ,alight. Yamamoto new that his battleships were too vulnerable to go on with fighter cover(as Pearl Harbour had proved how vulnerable battleships were), at 2.55am June 5th the Japanese abandoned the invasion of Midway. The Americans had lost one carrier, a destroyer and 147 aircraft, but the Japanese had lost 4 carriers. a cruiser, with 280 aircraft going to the bottom on the sunken carriers and a further 52 shot down, hundreds of their most experienced pilots killed, the battle of Midway was to shape the future of the war in the Pacific and to herald in a new age of war at sea, where the Aircraft carrier was both the most powerful and the most vulnerable