SOME IRRATIONAL NUMBERS Proposition 1. The square root of 2

... infinitude of primes. As he says, this is inevitably a proof by contradiction (unlike Euclid’s proof, which constructs new primes in a perfectly explicit way). The original statement is logically more complicated than what √ we actually prove in that it takes for granted that there is some real numb ...

... infinitude of primes. As he says, this is inevitably a proof by contradiction (unlike Euclid’s proof, which constructs new primes in a perfectly explicit way). The original statement is logically more complicated than what √ we actually prove in that it takes for granted that there is some real numb ...

Density of the Rationals and Irrationals in R

... where in the penultimate equation we used an → 0. ...

... where in the penultimate equation we used an → 0. ...

even, odd, and prime integers

... and it seems there are an infinite number of these, although they are considerably more sparse than other primes of the form 8n+7. We note that the Mersenne Primes all lie along the blue diagonal line in the 4th quadrant . Therefore 8n+7=2m-1 , from which it follows that (M[m]-7)/8 =2^(m-3)-1will a ...

... and it seems there are an infinite number of these, although they are considerably more sparse than other primes of the form 8n+7. We note that the Mersenne Primes all lie along the blue diagonal line in the 4th quadrant . Therefore 8n+7=2m-1 , from which it follows that (M[m]-7)/8 =2^(m-3)-1will a ...

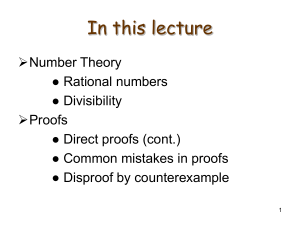

Class notes from November 18

... many times before, so I did not write out the work this time.) Hence, 103 · 4007 ≡ 1 (mod 6160), so 103 ≡ 4007−1 (mod 6160). Therefore, d = 103 is the decryption exponent. So δ(x) = x103 %6319. From the above example we see that one can find the decryption exponent fairly quickly once we’ve found th ...

... many times before, so I did not write out the work this time.) Hence, 103 · 4007 ≡ 1 (mod 6160), so 103 ≡ 4007−1 (mod 6160). Therefore, d = 103 is the decryption exponent. So δ(x) = x103 %6319. From the above example we see that one can find the decryption exponent fairly quickly once we’ve found th ...

Irrationality of Square Roots - Mathematical Association of America

... for α = 2. Geometric proofs must be tailored to each specific number and they are bound √ to get very complicated. For instance, one can show by computation that for α = 43, the ratios repeat only after 10 steps; a geometric proof would therefore have to contain dozens of points and line segments. U ...

... for α = 2. Geometric proofs must be tailored to each specific number and they are bound √ to get very complicated. For instance, one can show by computation that for α = 43, the ratios repeat only after 10 steps; a geometric proof would therefore have to contain dozens of points and line segments. U ...

Review of divisibility and primes

... factorization a = p1 · · · pn of a as a product of primes (where the pi are not necessarily distinct), and this factorization is unique up to reordering. Corollary 12. Suppose that α is a zero of a polynomial of the form xd + cd−1 xd−1 + . . . c1 x + c0 , where ci ∈ Z for all i, and suppose also tha ...

... factorization a = p1 · · · pn of a as a product of primes (where the pi are not necessarily distinct), and this factorization is unique up to reordering. Corollary 12. Suppose that α is a zero of a polynomial of the form xd + cd−1 xd−1 + . . . c1 x + c0 , where ci ∈ Z for all i, and suppose also tha ...

Integers and prime numbers. - People @ EECS at UC Berkeley

... Basic notation. Let IN denote the set of natural numbers {1, 2, 3, . . .} and let ZZ denote the set of all integers {. . . , −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, . . .}. Definitions. For two integers a, b, it is said that a divides b, and denoted by a|b, if b = ac for some integer c. Then a is a divisor, or factor, of ...

... Basic notation. Let IN denote the set of natural numbers {1, 2, 3, . . .} and let ZZ denote the set of all integers {. . . , −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, . . .}. Definitions. For two integers a, b, it is said that a divides b, and denoted by a|b, if b = ac for some integer c. Then a is a divisor, or factor, of ...

Problem List 3

... x and y are integers. Find the smallest number n such that given n lattice points in the plane, there exist two whose midpoint is also a lattice point. ...

... x and y are integers. Find the smallest number n such that given n lattice points in the plane, there exist two whose midpoint is also a lattice point. ...

Fermat's Last Theorem

In number theory, Fermat's Last Theorem (sometimes called Fermat's conjecture, especially in older texts) states that no three positive integers a, b, and c can satisfy the equation an + bn = cn for any integer value of n greater than two. The cases n = 1 and n = 2 were known to have infinitely many solutions. This theorem was first conjectured by Pierre de Fermat in 1637 in the margin of a copy of Arithmetica where he claimed he had a proof that was too large to fit in the margin. The first successful proof was released in 1994 by Andrew Wiles, and formally published in 1995, after 358 years of effort by mathematicians. The theretofore unsolved problem stimulated the development of algebraic number theory in the 19th century and the proof of the modularity theorem in the 20th century. It is among the most notable theorems in the history of mathematics and prior to its proof it was in the Guinness Book of World Records for ""most difficult mathematical problems"".

![[Part 1]](http://s1.studyres.com/store/data/008795996_1-7bdba077dfd2123ff356afe25da5d3ed-300x300.png)