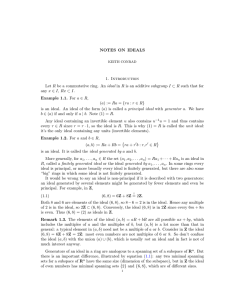

Ideals (prime and maximal)

... subtraction. So, it’s a subgroup of A, and finally since a′ (ax) = a(a′ x), it’s an ideal.///// Exercise. Show that (a1 , . . . , ak ) = { a1 x1 + · · · + ak xk | x1 , . . . , xk ∈ A }. Exercise. Suppose I and J are ideals of A. Then the ideal generated by I ∪ J is I + J := { y + z | y ∈ I & z ∈ J } ...

... subtraction. So, it’s a subgroup of A, and finally since a′ (ax) = a(a′ x), it’s an ideal.///// Exercise. Show that (a1 , . . . , ak ) = { a1 x1 + · · · + ak xk | x1 , . . . , xk ∈ A }. Exercise. Suppose I and J are ideals of A. Then the ideal generated by I ∪ J is I + J := { y + z | y ∈ I & z ∈ J } ...

Formal power series rings, inverse limits, and I

... Heuristically, this is what one would get by distributing the product in all possible ways, and then “collecting terms”: this is possible because, by (#), only finitely many terms rs rs0 ss0 occur for any particular t = ss0 . The ring has identity corresponding to the sum in which 1S has coefficient ...

... Heuristically, this is what one would get by distributing the product in all possible ways, and then “collecting terms”: this is possible because, by (#), only finitely many terms rs rs0 ss0 occur for any particular t = ss0 . The ring has identity corresponding to the sum in which 1S has coefficient ...

Hoofdstuk 1

... Here we also use induction. The case a = 2 is easy. Suppose that a > 2, and also suppose that uniqueness has been proven for the integers < a. If a = p1 · · · pr and a = q1 · · · qs are two ways of expressing a as a product of primes, then it follows that p1 | p1 · · · pr = q1 · · · qs . From Coroll ...

... Here we also use induction. The case a = 2 is easy. Suppose that a > 2, and also suppose that uniqueness has been proven for the integers < a. If a = p1 · · · pr and a = q1 · · · qs are two ways of expressing a as a product of primes, then it follows that p1 | p1 · · · pr = q1 · · · qs . From Coroll ...

The Proof Complexity of Polynomial Identities

... such that the equations c = a + b and d = a0 · b0 hold in R). Convention: 1. When speaking about equational proofs over some ring R we refer to the systems P(R). 2. Associativity of addition allows us to identify (a+b)+c with a + (b + c), orP simply a + b + c. We can also abbreviate n a1 + · · · + a ...

... such that the equations c = a + b and d = a0 · b0 hold in R). Convention: 1. When speaking about equational proofs over some ring R we refer to the systems P(R). 2. Associativity of addition allows us to identify (a+b)+c with a + (b + c), orP simply a + b + c. We can also abbreviate n a1 + · · · + a ...

06-valid-arguments

... • Proof: The only two perfect squares that differ by 1 are 0 and 1 – Thus, any other numbers that differ by 1 cannot both be perfect squares – Thus, a non-perfect square must exist in any set that contains two numbers that differ by 1 – Note that we didn’t specify which one it was! ...

... • Proof: The only two perfect squares that differ by 1 are 0 and 1 – Thus, any other numbers that differ by 1 cannot both be perfect squares – Thus, a non-perfect square must exist in any set that contains two numbers that differ by 1 – Note that we didn’t specify which one it was! ...