Holocaust_Human_Behavior copy

... to crowd out the ability to think. Man cannot be silenced, he can only be crowded into not speaking. Under all other conditions, even within the racing noise of our time, thinking is possible.”5 ...

... to crowd out the ability to think. Man cannot be silenced, he can only be crowded into not speaking. Under all other conditions, even within the racing noise of our time, thinking is possible.”5 ...

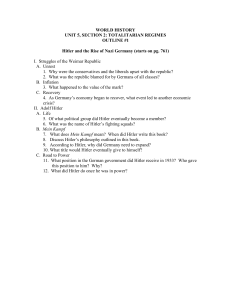

Honors 9 US History - Madeira City Schools

... 6. What two things did the NAZI (National Socialist German Workers) Party vow to do in Germany? ...

... 6. What two things did the NAZI (National Socialist German Workers) Party vow to do in Germany? ...

Religious views of Adolf Hitler

The religious views of Adolf Hitler are a matter of interest and debate. Hitler was raised by an increasingly anti-clerical father and devout Catholic mother. Baptized as an infant and confirmed at the age of fifteen, he ceased attending Mass and participating in the sacraments in later life. In adulthood Hitler became disdainful of Christianity, but in the pursuit and maintenance of power was prepared to delay clashes with the churches out of political considerations. Hitler's architect Albert Speer believed he had ""no real attachment"" to Catholicism, but that he had never formally left the Church. Hitler was not excommunicated prior to his suicide. The biographer John Toland noted Hitler's anticlericalism but considered him still in ""good standing"" with the Church by 1941, while historians such as Ian Kershaw, Joachim Fest and Alan Bullock agree that Hitler was anti-Christian - a view evidenced by sources such as the Goebbels Diaries, the memoirs of Speer, and the transcripts edited by Martin Bormann contained within Hitler's Table Talk. Goebbels wrote in 1941 that Hitler ""hates Christianity, because it has crippled all that is noble in humanity."" Many historians have come to the conclusion that Hitler's long-term aim was the eradication of Christianity in Germany, while others maintain that there is insufficient evidence for such a plan.Hitler's public relationship to religion has been characterized as one of opportunistic pragmatism. His regime did not publicly advocate for state atheism, but it did seek to reduce the influence of Christianity on society. Hitler himself was reluctant to make public attacks on the Church for political reasons, despite the urgings of Nazis like Bormann. Although he was skeptical of religion, he did not present himself to the public as an atheist, and spoke of belief in an ""almighty creator"". In private, he could be ambiguous. Evans wrote that Hitler repeatedly stated that Nazism was a secular ideology founded on science, which in the long run could not ""co-exist with religion"". In his semi-autobiographical Mein Kampf (1925/6) Hitler declared himself neutral in sectarian matters and supportive of separation between church and state, and he criticized political Catholicism. The book presents a nihilistic, Social Darwinist vision, in which the universe is ordered around principles of struggle between weak and strong, rather than on conventional Christian notions. In Mein Kampf, Hitler makes a number of religious allusions, claiming to be ""acting in accordance with the will of the Almighty Creator"" and to have been chosen by providence. In a 1922 speech he said,""My feelings as a Christian points me to my Lord and Savior as a fighter [...] who [...] recognized these Jews for what they were and summoned men to fight against them..."" In a 1928 speech, he said: ""We tolerate no one in our ranks who attacks the ideas of Christianity ... in fact our movement is Christian."" Given his hostility to Christianity, Laurence Rees wrote that ""The most persuasive explanation of these statements is that Hitler, as a politician, simply recognised the practical reality of the world he inhabited... Had Hitler distanced himself or his movement too much from Christianity, it is all but impossible to see how he could ever have been successful in a free election"". Alan Bullock wrote that even though Hitler frequently employed the language of ""divine providence"" in defence of his own myth, he ultimately shared with the Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin a materialistic outlook ""based on the nineteenth century rationalists' certainty that the progress of science would destroy all myths and had already proved Christian doctrine to be an absurdity"". According to Geoffrey Blainey, when the Nazis became the main opponent of Communism in Germany, Hitler saw Christianity as a temporary ally. He made various public comments against ""bolshevistic"" atheist movements, and in favor of so-called ""positive Christianity"" (a movement which sought to nazify Christianity by purging it of its Jewish elements, the Old Testament and key doctrines like the Apostles' Creed). While campaigning for office in the early 1930s, Hitler offered moderate public statements on Christianity, promising not to interfere with the churches if given power, and calling Christianity the foundation of German morality. Kershaw considers that use of such rhetoric served to placate potential criticism from the Church. According to Max Domarus, Hitler had fully discarded belief in the Judeo-Christian conception of God by 1937, but continued to use the word ""God"" in speeches.In office, the Hitler regime connived at a Kirchenkampf (lit. church struggle). While wary of open conflict with the churches, Hitler generally permitted or encouraged anti-church radicals such as Himmler, Goebbels and Bormann to perpetrate their persecutions of the churches. According to Evans, by 1939, 95% of Germans still called themselves Protestant or Catholic, with 3.5% 'Deist' (gottgläubig) and 1.5% atheist - most in these latter categories being ""convinced Nazis who had left their Church at the behest of the Party, which had been trying since the mid-1930s to reduce the influence of Christianity in society"". Gottgläubig"" (lit. ""believers in God""), had a non-denominational, nazified outlook on divine beliefs, often described as predominantly based on creationist and deistic views. Despite all the promotion for positive Christianity and the gottgläubig movement, the majority of the three million Nazi Party members continued to pay their church taxes and register as either Roman Catholic or mainline Protestant Christians. Hitler angered the churches by appointing the neo-pagan Alfred Rosenberg as official Nazi ideologist. He launched an effort toward coordination of German Protestants under a unified Protestant Reich Church under the Deutsche Christen movement, but the attempt failed - resisted by the Confessing Church. The Deutsche Christens differed from traditional Christians by rejecting the Hebrew origins of Christianity, preaching of an Aryan Jesus and saying that Saint Paul, as a Jew, had falsified Jesus' message - a theme Hitler repeated in private conversations, including, according to Susannah Heschel, in October 1941, when he made the decision to murder the Jews. From around 1934, Hitler had lost interest in supporting the Deutsche Christen. He moved early to eliminate political Catholicism, while agreeing to a Reich concordat with Rome which promised autonomy for the Catholic Church in Germany. His regime routinely violated the treaty, closed all Catholic organisations that weren't strictly religious, and perpetrated a persecution of the Catholic Church. Smaller religious minorities faced far harsher repression, with the Jews of Germany expelled for extermination on the grounds of racist ideology and Jehovah's Witnesses ruthlessly persecuted for refusing both military service and any allegiance to Hitlerism.Kershaw wrote that few people could really claim to ""know"" Hitler, who was ""a very private, even secretive individual"". Hitler's Table Talk has him often voicing stridently negative views of Christianity, in which Hitler said: ""The heaviest blow that ever struck humanity was the coming of Christianity. Bolshevism is Christianity's illegitimate child. Both are inventions of the Jew. The deliberate lie in the matter of religion was introduced into the world by Christianity."" Bullock wrote that Hitler was a rationalist and materialist who saw Christianity as a religion ""fit for slaves"" and against the natural law of selection and survival of the fittest. Toland, while noting Hitler's antagonism to the Pope and Church hierarchy, drew links between Hitler's Catholic background and his anti-Semitism. Following meetings with Hitler, General Gerhard Engel and Cardinal Michael von Faulhaber wrote that Hitler was a believer. Kershaw cites Faulhaber's case as an example of Hitler's ability to deceive ""even hardened critics"". Steigmann-Gall saw a ""Christian element"" in Hitler's early writings and evidence that he continued to hold Jesus in high esteem as an ""Aryan fighter"" who struggled against Jewry. Use of the term ""positive Christianity"" in the Nazi Party Program of the 1920s is commonly regarded as a tactical measure, but Steigmann-Gall believes it may have had an ""inner logic"" and been ""more than a political ploy"", though he notes that over time the Nazi movement became ""increasingly hostile to the churches"". John S. Conway considered that Steigmann-Gall's analysis differed from earlier interpretations only by ""degree and timing"", but that if Hitler's early speeches evidenced a sincere appreciation of Christianity, ""this Nazi Christianity was eviscerated of all the most essential orthodox dogmas"" leaving only ""the vaguest impression combined with anti-Jewish prejudice..."" which few would recognize as ""true Christianity"". Laurence Rees concludes that ""Hitler's relationship in public to Christianity - indeed his relationship to religion in general - was opportunistic. There is no evidence that Hitler himself, in his personal life, ever expressed any individual belief in the basic tenets of the Christian church"".