* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Punic Wars

Survey

Document related concepts

Roman army of the late Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman infantry tactics wikipedia , lookup

Constitutional reforms of Sulla wikipedia , lookup

Travel in Classical antiquity wikipedia , lookup

Roman army of the mid-Republic wikipedia , lookup

Roman historiography wikipedia , lookup

Education in ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Culture of ancient Rome wikipedia , lookup

Food and dining in the Roman Empire wikipedia , lookup

Roman agriculture wikipedia , lookup

Berber kings of Roman-era Tunisia wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

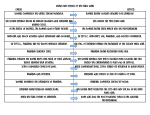

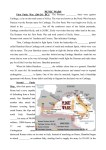

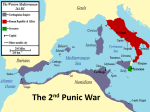

Question: What Does Punic Mean? Answer: Basically, Punic refers to the Punic people, i.e., the Phoenicians. It is an ethnic label. The English term 'Punic' comes from the Latin Poenus. First Punic War 264 - 241 B.C.: By the time of the first Punic War, Rome had expanded through Italy and was eager to control Magna Graecia. Carthage's involvement in the Greek area of southern Italy provided an opportunity and launched the first of 3 wars between rival Mediterranean powers. Second Punic War 218 - 201 B.C.: Although Rome eventually won the second Punic War, there were some tense moments as Carthage's skilled military leader, Hannibal, conquered Roman territory. As a side effect, Hannibal taught the Romans military tactics that they later used against him. Third Punic War 149 - 146 B.C.: By the time of the Third Punic War, Rome was more powerful than Carthage, but Carthage still represented an annoying threat, so Rome made sure Carthage wouldn't rise again. It is said that Rome salted the earth just to make sure. Punic Wars Overview The Punic Wars between Rome and Carthage spanned the years from 264 - 146 B.C. With both sides well-matched, the first two wars dragged on and on; eventual victory going not to the winner of a decisive battle, but to the side with the greatest stamina. The Third Punic War was something else entirely. Background to the Punic Wars In 509 B.C. Carthage and Rome signed a friendship treaty. In 306, by which time the Romans had conquered almost the entire Italian peninsula, the two powers reciprocally recognized a Roman sphere of influence over Italy and a Carthaginian one over Sicily. But Italy was determined to secure dominance over all of Magna Graecia (the areas settled by Greeks in and around Italy), even if it meant interfering with the dominance of Carthage in Sicily. Events Triggering the First Punic War Turmoil in Messana, Sicily, provided the opportunity the Romans were looking for. Mamertine mercenaries controlled Messana, so when Hiero, tyrant of Syracuse, attacked the Mamertines, the Mamertines asked the Phoenicians for help. They obliged and sent in a Carthaginian garrison. Then, having second thoughts about the Carthaginian military presence, the Mamertines turned to the Romans for help. The Romans sent in an expeditionary force, small, but sufficient to send the Phoenician garrison back to Carthage. Carthage and Rome Both Send Troops Carthage responded by sending in a larger force, to which the Romans responded with a full consular army. In 262 B.C. Rome won many small victories, giving it control over almost the entire island. But the Romans needed control of the sea for final victory and Carthage was a naval power. Conclusion to the First Punic War With both sides balanced, the war between Rome and Carthage continued for 20 more years until the war-weary Phoenicians just gave up in 241. According to J.F. Lazenby, author of The First Punic War, "To Rome, wars ended when the Republic dictated its terms to a defeated enemy; to Carthage, wars ended with a negotiated settlement." At the end of the First Punic War, Rome won a new province, Sicily, and began to look further. (This made the Romans empire builders.) Carthage, on the other hand, had to compensate Rome for its heavy losses. Although the tribute was steep, it didn't keep Carthage from continuing as a worldclass trading power. Second Punic War Timeline At the end of the first Punic War, in 241 B.C., Carthage agreed to pay a steep tribute to Rome, but it wasn't enough to devastate the nation of traders and merchants: Rome and Carthage would soon fight again. In the interim between Punic Wars I and II, the Phoenician hero and military leader Hamilcar Barca conquered much of Spain, while Rome took Corsica. Hamilcar longed to get revenge against the Romans for the defeat in Punic War I, but realizing that wasn't to be, he taught hatred of Rome to his son, Hannibal. Hannibal Scipio Publius Cornelius Africanus Major The Second Punic War broke out in 218 when Hannibal took control of the Greek city and Roman ally, Saguntum (in Spain). Rome thought it would be easy to defeat Hannibal, but Hannibal was full of surprises, including his manner of entering the Italic peninsula from Spain. Leaving 20,000 troops with his brother Hasdrubal, Hannibal went further north on the Rhone River than the Romans expected and crossed the river with his elephants on flotation devices. He didn't have as much manpower as the Romans, but he counted on the support and alliance of Italian tribes unhappy with Rome. Hannibal reached the Po Valley with less than half his men. He had also encountered unexpected resistance from local tribes, although he did manage to recruit Gauls. This meant he had 30,000 troops by the time he met the Romans in battle. Hannibal's Greatest Victory: The Battle of Cannae (216 B.C.) Hannibal won battles in Trebia and at Lake Trasimene, and then continued through the Apennine Mountains that run down through much of Italy like a spine. With troops from Gaul and Spain on his side, Hannibal won another battle, at Cannae, against Lucius Aemilius. At the Battle of Cannae, the Romans lost thousands of troops, including their leader. The historian Polybius describes both sides as gallant. He writes about the substantial losses: "Of the infantry ten thousand were taken prisoners in fair fight, but were not actually engaged in the battle: of those who were actually engaged only about three thousand perhaps escaped to the towns of the surrounding district; all the rest died nobly, to the number of seventy thousand, the Carthaginians being on this occasion, as on previous ones, mainly indebted for their victory to their superiority in cavalry: a lesson to posterity that in actual war it is better to have half the number of infantry, and the superiority in cavalry, than to engage your enemy with an equality in both. On the side of Hannibal there fell four thousand Celts, fifteen hundred Iberians and Libyans, and about two hundred horse." Besides trashing the countryside (which both sides did in an effort to starve the enemy), Hannibal terrorized the towns of southern Italy in an effort to gain allies. The next general to confront Hannibal was more successful; that is, there was no decisive victory. However, the senate in Carthage refused to send in enough troops to enable Hannibal to win. So Hannibal turned to his brother Hasdrubal for help. Unfortunately for Hannibal, Hasdrubal was killed en route to join him, marking the first decisive Roman victory. More than 10,000 Carthaginians died at the Battle of Metaurus in 207 B.C. Scipio Meanwhile, Scipio invaded North Africa. The Carthaginian Senate responded by recalling Hannibal. The Romans under Scipio fought the Phoenicians under Hannibal at Zama. Hannibal, who no longer had an adequate cavalry, was unable to follow his preferred tactics. Instead, Scipio routed the Carthaginians using the same strategy Hannibal had used at Cannae. Hannibal put an end to the Second Punic War. Scipio's stringent terms of surrender were to: hand over all warships and elephants not make war without permission of Rome pay Rome 10,000 talents over the next 50 years. The terms included an additional, difficult proviso: should armed Carthaginians cross a border the Romans drew in the dirt, it automatically meant war with Rome. This meant that the Carthaginians could be put in a position where they might not be able to defend their own interests. Third Punic War 149 - 146 B.C. By the end of the Second Punic War, the Romans so hated the Carthaginians that they wanted to destroy it. The story is told that when they finally had their revenge winning the Third Punic War, the Romans salted the fields so the Carthaginians could no longer live there. By 201 B.C., the end of the Second Punic War (the war where Hannibal and his elephants crossed the Alps), Carthage no longer had her empire, but she was still a shrewd trading nation. By the middle of the second century Carthage was thriving and it was hurting the trade of those Romans who had investments in North Africa. Marcus Cato, a respected senator, began to clamor "Carthago delenda est!" "Carthage must be destroyed!" Meanwhile, tribes neighbouring Carthage knew that according to the treaty between Carthage and Rome, if Carthage overstepped the line drawn in the sand, it would be interpreted as an act of aggression against Rome. These neighbours took advantage of this reason to feel secure and made hasty raids into Carthaginian territory, knowing their victims couldn't pursue them. Eventually, Carthage could stand these incursions no longer. In 149 they armed themselves and went after the Numidians. Rome declared war on the basis of the broken treaty. Although Carthage didn't stand a chance, the war was drawn out for three years. Eventually a descendant of Scipio Africanus, Scipio Aemilianus, defeated the starved citizens of the besieged city of Carthage. After killing or selling all the inhabitants into slavery, the Romans razed (possibly salting the land) and burned the city. No one was allowed to live there.* Cato's motto had been carried out.