* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Mitral valve stenosis - Great Ormond Street Hospital

Survey

Document related concepts

Heart failure wikipedia , lookup

Quantium Medical Cardiac Output wikipedia , lookup

Coronary artery disease wikipedia , lookup

Electrocardiography wikipedia , lookup

Rheumatic fever wikipedia , lookup

Myocardial infarction wikipedia , lookup

Pericardial heart valves wikipedia , lookup

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy wikipedia , lookup

Jatene procedure wikipedia , lookup

Cardiac surgery wikipedia , lookup

Aortic stenosis wikipedia , lookup

Congenital heart defect wikipedia , lookup

Dextro-Transposition of the great arteries wikipedia , lookup

Transcript

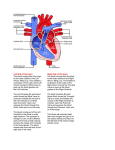

Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust: Information for Families Mitral valve stenosis This information sheet from Great Ormond Street Hospital explains the causes, symptoms and treatment of mitral valve stenosis and where to get help. Mitral valve stenosis is usually a congenital heart defect – that is, it was present when the child was born. Around eight in every 1000 babies born have a congenital heart defect. The normal heart The heart consists of four chambers – two upper filling chambers (atria) and two lower pumping chambers (ventricles). In between each atrium and ventricle is a valve that stops blood flowing backwards. There is also a valve where the pulmonary artery and aorta join the heart. The function of the heart is to pump blood around the body. Blood comes into the right atrium from the body and goes through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle. From here, it is pumped up the pulmonary artery to the lungs to pick up oxygen. Oxygen-rich blood comes back to the heart through the pulmonary veins into the left atrium. It flows through the mitral valve into the left ventricle. This pumps the blood into the aorta and from there around the body. Mitral valve stenosis Aorta Pulmonary artery Left atrium Mitral valve Right atrium Tricuspid valve Sheet 1 of 3 The right and left sides of the heart are divided by a thick wall of heart muscle called the septum. Left ventricle Ref: 2013F1108 Mitral valve stenosis is usually a congenital heart defect – that is, it was present when the child was born. Around eight in every 1000 babies born have a congenital heart defect. Congenital mitral valve stenosis means that the valve between the left pumping chamber (left ventricle) and left filling chamber (left atrium) is narrower than it should be. Blood flows from the left atrium into the left ventricle and then on to the © GOSH NHS Foundation Trust October 2013 rest of the body. As the valve is narrow, blood collects in the left atrium, builds up pressure and may flow back to the lungs. Even if the mitral valve is the main problem, some children with mitral stenosis have other abnormalities on the left side of the heart, perhaps in the aortic valve area or in the aorta as it leaves the heart. What causes congenital mitral valve stenosis? The heart is formed early in pregnancy but doctors do not fully understand why some children’s hearts do not develop properly . For the majority of babies born with congenital mitral valve stenosis, doctors never find a cause. However, the chance of a child having this condition increases a little if one or both parents had a congenital heart defect. Occasionally some conditions such as diabetes or medicines taken during pregnancy can also increase the risk. Congenital heart defects are more common in children with other congenital conditions. What are the signs and symptoms of congenital mitral valve stenosis? Symptoms are often present from birth when the baby can be seriously ill or symptoms can develop within the first two years of life. There may be feeding difficulties which lead to poor weight gain and breathlessness after exertion. Sheet 2 of 3 Ref: 2013F1108 If the problem progresses, the child’s nails, lips and skin may develop a blue tinge as there is not enough oxygenrich blood circulating around the body. Gradually the heart becomes weaker as it has to work much harder to pump blood around the body. How is congenital mitral valve stenosis normally diagnosed? A child’s defect may have been diagnosed antenatally by our foetal team and will be confirmed on admission. Doctors will use chest X-rays, electrocardiograms (ECG) and echocardiograms (Echo) to diagnose congenital mitral valve stenosis. An ECG measures the electric current passing through the heart. An Echo is an ultrasound of the heart and shows not only the structure of the heart but the blood flow through it. Some children also have a cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan which uses a strong magnetic field, radio waves and a computer to make a very detailed image of the heart. How is congenital mitral valve stenosis treated? Doctors will suggest treatment depending on the narrowness of the mitral valve stenosis and the results of the diagnostic tests. Some mild mitral valve stenosis, where the valve is only a little narrower than normal, might not need any treatment but will still need to be assessed regularly. © GOSH NHS Foundation Trust October 2013 If the narrowing is severe enough to interfere with a child’s progress the treatment options will depend on the severity, the size and age of the child and whether other valves or blood vessels need attention. In young children, open heart surgery to repair or replace the valve may be the first option. In some older children treatment carried out using a catheter (thin plastic tube) threaded through the blood vessel system to the heart might be possible. Further information and support Contact one of the support organisations below: British Heart Foundation Tel (Heart Help Line): 0300 330 3311 (calls charged at local rate) Website: www.bhf.org.uk Heartline Tel: 03300 224 466 (local rate number) Website: www.heartline.org.uk What happens next? All children who have had mitral valve stenosis will need to come to hospital for regular check ups. This will usually involve repeat Echo scans to check that the valve is not becoming narrower. Other tests such as an ECG might also be needed. If the valve has been replaced, this will involve life long follow-up. A manmade valve will need lifelong blood thinning medicine to prevent the valve clotting. Notes Compiled by the Web team in collaboration with the Child and Family Information Group Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children NHS Foundation Trust Great Ormond Street London WC1N 3JH www.gosh.nhs.uk Sheet 3 of 3 Ref: 2013F1108 © GOSH NHS Foundation Trust October 2013