* Your assessment is very important for improving the workof artificial intelligence, which forms the content of this project

Download Chapter 1 The Electric Force

Casimir effect wikipedia , lookup

Work (physics) wikipedia , lookup

Speed of gravity wikipedia , lookup

Potential energy wikipedia , lookup

Magnetic monopole wikipedia , lookup

Fundamental interaction wikipedia , lookup

Introduction to gauge theory wikipedia , lookup

Anti-gravity wikipedia , lookup

Electrical resistance and conductance wikipedia , lookup

History of electromagnetic theory wikipedia , lookup

Time in physics wikipedia , lookup

Electromagnetism wikipedia , lookup

Electrical resistivity and conductivity wikipedia , lookup

Maxwell's equations wikipedia , lookup

Field (physics) wikipedia , lookup

Aharonov–Bohm effect wikipedia , lookup

Lorentz force wikipedia , lookup

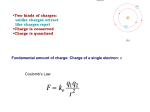

General physics Phys 2180 Chapter 1 The Electric Force 1. Properties of the Electric Charges 1- There are two kinds of the electric charges in the nature, which are positive and negative charges. 2- The charges of opposite sign attract one another and the charges of the same sign repel one another. 3- The Charge is quantized. 2. Units of the Electric Charge • 1 milli coulomb (1 mC) = 10-3 C • 1 micro coulomb (1 µC) = 10-6 C • 1 nano coulomb (1 nC) = 10-9 C • 1 pico coulomb (1pC) = 10-12 C 1 General physics Phys 2180 3. Coulomb’s Law Charles Coulomb (1736 - 1806) measured the magnitudes of the electric forces between charged objects using the torsion balance shown in Figure (1). Figure 1 Coulomb’s torsion balance. From Coulomb’s experiments, we can generalize the following properties of the electric force exerted between two stationary charged particles: • The electric force is inversely proportional to the square of the separation r between the particles and directed along the line joining them F ∝ 1 ; r2 • The electric force is proportional to the product of the charges q1 and q2 on the two particles F ∝ q1 q 2 ; •The electric force is attractive if the charges are of opposite sign and repulsive if the charges have the same sign; • The electric force is a conservative force. 2 General physics Phys 2180 We will use the term point charge to mean a particle of zero size that carries an electric charge. We can express Coulomb’s law as an equation giving the magnitude of the electric force (sometimes called the Coulomb force) between two point charges: Fe = K e q1 q 2 r2 Where ke is a constant called the Coulomb constant. The value of the Coulomb constant depends on the choice of units. The Coulomb constant ke in SI units has the value K= 1 4πε 0 = 9 × 10 9 N.m 2 /C 2 where the constant εo (lowercase Greek epsilon) is known as the permittivity of free space and has the value ε o = 8.85 10 -12 C 2 / N.m 2 The smallest unit of charge e known in nature is the charge on an electron (- e) or a proton (+ e) and has a magnitude e = 1.602 x 10 −19 C Example 1 (The Hydrogen Atom) The electron and proton of a hydrogen atom are separated (on the average) by a distance of approximately 5.3 x 10-11 m. Find the magnitudes of the electric force and the gravitational force between the two particles. 3 General physics Phys 2180 Solution From Coulomb’s law, we find that the magnitude of the electric force is -m النواة+ M Fe = K e q1 q 2 e x −e = Ke 2 r r2 (1.6 x 10 ) (5.3 x 10 ) −19 2 = 9 x 10 9 x −11 2 = 8.2 x 10 −8 N Using Newton’s law of universal gravitation and above Table for the particle masses, we find that the magnitude of the gravitational force is FG = G = (6.67 × 10 −11 mM r2 )( )( 2 N.m 2 /Kg 2 9.11 × 10 −31 Kg 1.67 × 10 − 27 Kg (5.3 × 10 = 3.63 × 10 − 47 −11 m ) ) 2 N FE 8.23 × 10 −8 = 2.27 × 10 39 = − 47 FG 3.62 × 10 Thus, the gravitational force between charged atomic particles is negligible when compared with the electric force. 4 General physics Phys 2180 Figure (4) When dealing with Coulomb’s law, you must remember that force is a vector quantity and must be treated accordingly. The law expressed in vector form for the electric force exerted by a charge q1 on a second charge q2, written F12, is F12 = K e q1 q 2 ∧ r r2 where rˆ is a unit vector directed from q1 toward q2, as shown in Figure 4-a. Because the electric force obeys Newton’s third law, the electric force exerted by q2 on q1 is equal in magnitude to the force exerted by q1 on q2 and in the opposite direction; that is, F21 = - F12. 5 General physics Phys 2180 Figure (5) if five charges are present, as shown in figure(5), then the resultant force exerted by particles 2, 3, 4,and 5 on particle 1 is F1 = F21 + F31 + F41 + F51 Example 2 Consider three point charges located at the corners of a right triangle as shown in Figure 6, where q1= q3 = 5.0 µC, q2= - 2.0 µC, and a = 0.10 m. Find the resultant force exerted on q3. 6 General physics Phys 2180 y F13 F13 y F13 x + x q3 Figure (6) Solution First, note the direction of the individual forces exerted by q1 and q2 on q3. The force F23 exerted by q2 on q3 is attractive because q2 and q3 have opposite signs. The force F13 exerted by q1 on q3 is repulsive because both charges are positive. The magnitude of F23 is In the coordinate system shown in Figure(6), the attractive force F23 is to the left (in the negative x direction). The magnitude of the force F13 exerted by q1 on q3 is 7 General physics Phys 2180 The repulsive force F13 makes an angle of 45° with the x axis. Therefore, the x and y components of F13 are equal, with magnitude given by F13 cos 45° = 7.9 N. We can also express the resultant force acting on q3 in unit vector form as Example 3 Where Is the Resultant Force Zero? Three point charges lie along the x axis as shown in Figure (7). The positive charge q1 = 15.0 µC is at x = 2.00 m, the positive charge q2 = 6.00 µC is at the origin, and the resultant force acting on q3 is zero. What is the x coordinate of q3? 8 General physics Phys 2180 Figure (7) Solution Because q3 is negative and q1 and q2 are positive, the forces F13 and F23 are both attractive, as indicated in Figure (7). From Coulomb’s law, F13 and F23 have magnitudes For the resultant force on q3 to be zero, F23 must be equal in magnitude and opposite in direction to F13. Setting the magnitudes of the two forces equal, we have Noting that ke and q3 are common to both sides and so can be dropped, we solve for x and find that 9 General physics Phys 2180 Solving this quadratic equation for x, we find that the positive root is x = 0.775 m There is also a second root, x = - 3.44 m. This is another location at which the magnitudes of the forces on q3 are equal, but both forces are in the same direction at this location. .Problems (1) Two protons in an atomic nucleus are typically separated by a distance of 2 x 1015 m. The electric repulsion force between the protons is huge, but the attractive nuclear force is even stronger and keeps the nucleus from bursting apart. What is the magnitude of the electric force between two protons separated by 2.00 x 1015 m? (2) Three point charges are located at the corners of an equilateral triangle as shown in Figure 9. Calculate the resultant electric force on the 7.00- µC charge. Figure (9) (3) Two identical conducting small spheres are placed with their centers 0.300m apart. One is given a charge of 12.0 nC and the other a charge of -18.0 nC. (a) Find the electric force exerted by one sphere on the other. (b) What If? The spheres are connected by a conducting wire. Find the electric force between the two after they have come to equilibrium. 10 General physics Phys 2180 Problems solutions (1) (2) 11 General physics Phys 2180 (3) 12 General physics Phys 2180 Chapter 2 Electric Field Two field forces have been introduced into our study so far—the gravitational force Fg and the electric force Fe . The gravitational field g at a point in space equal to the gravitational force Fg acting on a test particle of mass m divided by that mass: g = Fg m . The electric field vector E at a point in space is defined as the electric force Fe acting on a positive test charge q0 placed at that point divided by the test charge: E = Fe qo The vector E has the SI units of newtons per coulomb (N/C). Note that E is the field produced by some charge or charge distribution separate from the test charge—it is not the field produced by the test charge itself. Also, note that the existence of an electric field is a property of its source—the presence of the test charge is not necessary for the field to exist. The test charge serves as a detector of the electric field. The Equation electric field can be rearranged as Fe = E q o where we have used the general symbol q for a charge. This equation gives us the force on a charged particle placed in an electric field. If q is positive, the force is in the same direction as the field. If q is negative, the force and the field are in opposite directions ( as shown in the following figure). 13 General physics Phys 2180 Figure (1) To determine the direction of an electric field, consider a point charge q as a source charge. This charge creates an electric field at all points in space surrounding it. A test charge q0 is placed at point P, a distance r from the source charge, as in Figure 1-a. According to Coulomb’s law, the force exerted by q on the test charge is Fe = K e Q E= q qo ∧ r r2 Fe qo ∴ E = Ke q ∧ r r2 where rˆ is a unit vector directed from q toward q0. If the source charge q is positive, Figure 1-b shows the situation with the test charge removed—the source charge sets up an electric field at point P, directed away from q. If q is negative, as in Figure 1-c, the force on the test charge is toward the source charge, so the electric field at P is directed toward the source charge, as in Figure 1-d. 14 General physics Phys 2180 Note that at any point P, the total electric field due to a group of source charges equals the vector sum of the electric fields of all the charges. Thus, the electric field at point P due to a group of source charges can be expressed as the vector sum ∧ Where ri is the distance from the i th source charge qi to the point P and ri is a unit vector directed from qi toward P. Example 1 ( Electric Field Due to Two Charges) A charge q1= 7.0 µC is located at the origin, and a second charge q2 = -5.0 µC is located on the x axis, 0.30 m from the origin (Figure 2). Find the electric field at the point P, which has coordinates (0, 0.40) m. Figure (2) 15 General physics Phys 2180 Solution: First, let us find the magnitude of the electric field at P due to each charge. The fields E1 due to the 7.0 µC charge and E2 due to the - 5.0 µC charge are shown in Figure 2. Their magnitudes are The vector E1 has only a y component. The vector E2 has an x component given by E2 Cos θ = 3 4 E2 and a negative y component given by E2 Sin θ = E2. Hence, we can 5 5 express the vectors as The resultant field E at P is the superposition of E1 and E2: From this result, we find that E makes an angle φ of 66° with the positive x axis and has a magnitude of 2.7 x 105 N/C Example 2 ( Electric Field of a Dipole) An electric dipole is defined as a positive charge + q and a negative charge - q separated by a distance 2a. For the dipole shown in Figure 3, find the electric field E at P due to the dipole, where P is a distance y >> a from the origin. 16 General physics Phys 2180 Solution: At P, the fields E1 and E2 due to the two charges are equal in magnitude because P is equidistant from the charges. The total field is E = E1 + E2 , where Figure (3) The y components of E1 and E2 cancel each other, and the x components are both in the positive x direction and have the same magnitude. Therefore, E is parallel to the x axis and has a magnitude equal to 2 E1 Cos θ. From Figure 3 we see that Cos θ = a = r a (y Therefore 17 2 + a2 ) 1 2 General physics Phys 2180 Because y >>a , we can neglect a2 compared to y2 and write Electric Field Lines Representative electric field lines for the field due to a single positive point charge are shown in Figure 8 a. The electric field lines representing the field due to a single negative point charge are directed toward the charge (Fig.8 b). In either case, the lines are along the radial direction and extend all the way to infinity. Note that the lines become closer together as they approach the charge; this indicates that the strength of the field increases as we move toward the source charge. Figure (8) The rules for drawing electric field lines are as follows: • The lines must begin on a positive charge and terminate on a negative charge. In the case of an excess of one type of charge, some lines will begin or end infinitely far away. 18 General physics • Phys 2180 The number of lines drawn leaving a positive charge or approaching a negative charge is proportional to the magnitude of the charge. • No two field lines can cross or intersect with one another. 19 General physics Phys 2180 Problems (1) In the figure bellow, determine the point (other than infinity) at which the electric field is zero. Solution: 20 General physics Phys 2180 (2) Three point charges are arranged as shown in the figure bellow: (a) Find the vector electric field that the 6.00-nC and "3.00-nC charges together create at the origin. (b) Find the vector force on the 5.00-nC charge. 21 General physics Phys 2180 Solution: (3) Four identical point charges (q = +10.0 µC) are located on the corners of a rectangle as shown in the figure bellow. The dimensions of the rectangle are L= 60.0 cm and W = 15.0 cm. Calculate the magnitude and direction of the resultant electric force exerted on the charge at the lower left corner by the other three charges. 22 General physics Phys 2180 Solution: 23 General physics Phys 2180 Chapter 3 Electric Flux and Gauss’s Law 1- Electric Flux Figure (1) Consider an electric field that is uniform in both magnitude and direction, as shown in Figure 1. The total number of lines penetrating the surface is proportional to the product E A. This product of the magnitude of the electric field E and surface area A perpendicular to the field is called the electric flux ΦE. ΦE = E A From the SI units of E and A, we see that ΦE has units of newton-meters squared per coulomb (N. m2/ C.) Electric flux is proportional to the number of electric field lines penetrating some surface. Example 1 What is the electric flux through a sphere that has a radius of 1.0 m and carries a charge of +1.0 µC at its center? Solution The magnitude of the electric field is giving by 24 General physics Phys 2180 The field points radially outward and is therefore everywhere perpendicular to the surface of the sphere. The flux through the sphere (whose surface area A = 4 πr2 = 12.6 m2) is thus If the surface under consideration is not perpendicular to the field, as show in Figure 2, the electric flux ΦE given by ΦE = E A Cos θ Figure (2) From this equation, we see that the flux through a surface of fixed area A has a maximum value EA when the surface is perpendicular to the field (when the normal to the surface is parallel to the field, that is, θ = 0° in Figure 2); the flux is zero when the surface is parallel to the field (when the normal to the surface is perpendicular to the field, that is, θ = 90°). 25 General physics Phys 2180 2- Gauss’s Law In this section we describe a general relationship between the net electric flux through a closed surface (often called a gaussian surface) and the charge enclosed by the surface. This relationship, known as Gauss’s law, is of fundamental importance in the study of electric fields. Figure (3) Let us again consider a positive point charge q located at the center of a sphere of radius r, as shown in Figure 3. we know that the magnitude of the electric field everywhere on the surface of the sphere is E = Ke q r2 The field lines are directed radially outward and hence are perpendicular to the surface at every point on the surface. That is, at each surface point, E is parallel to the vector ∆Ai representing a local element of area ∆Ai surrounding the surface point. Therefore, the net flux through the Gaussian surface is 26 General physics Phys 2180 where we have moved E outside of the integral because E is constant over the surface and given by E = K e q r2 Furthermore, because the surface is spherical, Hence, the net flux through the Gaussian surface is According to the superposition principle, which states that the electric field due to many charges is the vector sum of the electric fields produced by the individual charges. Therefore, we can express the flux through any closed surface as Figure (4) Figure 4 shows that the number of lines through S1 is equal to the number of lines through the non-spherical surfaces S2 and S3. Therefore, we conclude that the net flux 27 General physics Phys 2180 through any closed surface surrounding a point charge q is given by q εo and is independent of the shape of that surface. Figure (5) Consider the system of charges shown in Figure 5. The surface S surrounds only one charge, q1; hence, the net flux through S is q1 εo . The flux through S due to charges q2, q3, and q4 outside it is zero because each electric field line that enters S at one point leaves it at another. The surface S\ surrounds charges q2 and q3; hence, the net flux through it is q 2 + q3 εo . Finally, the net flux through surface S\\ is zero because there is no charge inside this surface. That is, all the electric field lines that enter S\\ at one point leave at another. Notice that charge q4 does not contribute to the net flux through any of the surfaces because it is outside all of the surfaces. Gauss’s law, which is a generalization of what we have just described, states that the net flux through any closed surface is 28 General physics Phys 2180 where qin represents the net charge inside the surface and E represents the electric field at any point on the surface. Example 2 (The Electric Field Due to a Point Charge) Starting with Gauss’s law, calculate the electric field due to an isolated point charge q. Solution: We choose a spherical gaussian surface of radius r centered on the point charge, as shown in Figure 6. The electric field due to a positive point charge is directed radially outward by symmetry and is therefore normal to the surface at every point. Thus, E is parallel to dA at each point. Therefore, Gauss’s law gives where we have used the fact that the surface area of a sphere is 4πr2. Now, we solve for the electric field: 29 General physics Phys 2180 Problems (1) An electric field with a magnitude of 3.50 kN/C is applied along the x axis. Calculate the electric flux through a rectangular plane 0.350 m wide and 0.700 m long assuming that (a) the plane is parallel to the yz plane; (b) the plane is parallel to the xy plane; (c) the plane contains the y axis, and its normal makes an angle of 40.0° with the x axis. Solution: (2) Four closed surfaces, S1 through S4, together with the charges -2Q , +Q , and -Q are sketched in the figure bellow. (The colored lines are the intersections of the surfaces with the page.) Find the electric flux through each surface. 30 General physics Phys 2180 Solution: (3) A charge of 170 µC is at the center of a cube of edge 80.0 cm. (a) Find the total flux through each face of the cube. (b) Find the flux through the whole surface of the cube. Solution: 31 General physics Phys 2180 Chapter 4 Electric Potential Potential Difference and Electric Potential When a test charge qo is placed in an electric field E created by some source charge distribution, the electric force acting on the test charge is qo E. The force qo E is conservative because the force between charges described by Coulomb’s law is conservative. When the test charge is moved in the field by some external agent, the work done by the field on the charge is equal to the negative of the work done by the external agent causing the displacement ds. For an infinitesimal displacement ds of a charge, the work done by the electric field on the charge is F. ds = qoE. ds. As this amount of work is done by the field, the potential energy of the charge–field system is changed by an amount dU = qoE. ds. For a finite displacement of the charge from point A to point B, the change in potential energy of the system ∆U = UB - UA is The integration is performed along the path that qo follows as it moves from A to B. Because the force qo E is conservative, this line integral does not depend on the path taken from A to B. The potential energy per unit charge U/qo is independent of the value of qo and has a value at every point in an electric field. This quantity U/qo is called the electric potential (or simply the potential) V. Thus, the electric potential at any point in an electric field is 32 General physics Phys 2180 The potential difference ∆V= VB - VA between two points A and B in an electric field is defined as the change in potential energy of the system when a test charge is moved between the points divided by the test charge qo: Potential difference should not be confused with difference in potential energy. The potential difference between A and B depends only on the source charge distribution (consider points A and B without the presence of the test charge), while the difference in potential energy exists only if a test charge is moved between the points. Electric potential is a scalar characteristic of an electric field, independent of any charges that may be placed in the field. If an external agent moves a test charge from A to B without changing the kinetic energy of the test charge, the agent performs work which changes the potential energy of the system: W = ∆U. The work done by an external agent in moving a charge q through an electric field at constant velocity is The SI unit of both electric potential and potential difference is joules per coulomb, which is defined as a volt (V): 33 General physics Phys 2180 That is, 1 J of work must be done to move a 1-C charge through a potential difference of 1 V. Potential Differences in a Uniform Electric Field Consider a uniform electric field directed along the negative y axis, as shown in Figure 1-a. Let us calculate the potential difference between two points A and B separated by a distance |s| = d, where s is parallel to the field lines. Because E is constant, we can remove it from the integral sign; this gives The negative sign indicates that the electric potential at point B is lower than at point A; that is, VB < VA. Electric field lines always point in the direction of decreasing electric potential, as shown in Figure 1-a. Figure (1) 34 General physics Phys 2180 Now suppose that a test charge qo moves from A to B. The change in the potential energy of the charge–field system is given by From this result, we see that : (1) if qo is positive, then ∆U is negative. We conclude that a system consisting of a positive charge and an electric field loses electric potential energy when the charge moves in the direction of the field. This means that an electric field does work on a positive charge when the charge moves in the direction of the electric field. (2) If qo is negative, then ∆U is positive and the situation is reversed: A system consisting of a negative charge and an electric field gains electric potential energy when the charge moves in the direction of the field. Figure (2) Now consider the more general case of a charged particle that moves between A and B in a uniform electric field such that the vector s is not parallel to the field lines, as shown in Figure 2. In this case the potential difference is given by 35 General physics Phys 2180 where again we are able to remove E from the integral because it is constant. The change in potential energy of the charge–field system is Finally, we conclude that all points in a plane perpendicular to a uniform electric field are at the same electric potential. We can see this in Figure 2, where the potential difference VB - VA is equal to the potential difference VC - VA. Therefore, VB = VC. The name equipotential surface is given to any surface consisting of a continuous distribution of points having the same electric potential. Example 1 (The Electric Field Between Two Parallel Plates of Opposite Charge) A battery produces a specified potential difference ∆V between conductors attached to the battery terminals. A 12-V battery is connected between two parallel plates, as shown in Figure 3. The separation between the plates is d = 0.30 cm, and we assume the electric field between the plates to be uniform. Find the magnitude of the electric field between the plates. Figure (3) 36 General physics Phys 2180 Solution: Example 2 (Motion of a Proton in a Uniform Electric Field) A proton is released from rest in a uniform electric field that has a magnitude of 8.0 x 104 V/m (Figure 4). The proton undergoes a displacement of 0.50 m in the direction of E. (A) Find the change in electric potential between points A and B. (B) Find the change in potential energy of the proton–field system for this displacement. Figure (4) (A) The change in electric potential between points A and B (B) the change in potential energy of the proton–field system for this displacement 37 General physics Phys 2180 Electric Potential and Potential Energy Due to Point Charges To find the electric potential at a point located a distance r from the charge, we begin with the general expression for potential difference: Figure (5) where A and B are the two arbitrary points shown in Figure 5. At any point in space, the electric field due to the point charge is 38 General physics Phys 2180 E = Ke q ∧ r r2 where rˆ is a unit vector directed from the charge toward the point. The quantity E . ds can be expressed as Because the magnitude rˆ of is 1, the dot product rˆ. ds = ds cos θ (, where θ is the angle between rˆ and ds. Furthermore, ds cos θ is the projection of ds onto r; thus, ds cos θ = dr the expression for the potential difference becomes This equation shows us that the integral of E. ds is independent of the path between points A and B. Multiplying by a charge qo that moves between points A and B, we see that the integral of qo E. ds is also independent of path. It is customary to choose the reference of electric potential for a point charge to be V = 0 at rA → ∞ . With this reference choice, the electric potential created by a point charge at any distance r from the charge is We obtain the electric potential resulting from two or more point charges by applying the superposition principle. That is, the total electric potential at some point P 39 General physics Phys 2180 due to several point charges is the sum of the potentials due to the individual charges. For a group of point charges, we can write the total electric potential at P in the form Figure (6) Example 3 (The Electric Potential Due to Two Point Charges) A charge q1= 2.00 µC is located at the origin, and a charge q2 = - 6.00 µC is located at (0, 3.00) m, as shown in Figure 6-a. (A) Find the total electric potential due to these charges at the point P, whose coordinates are (4.00, 0) m. (B) Find the change in potential energy of the system of two charges plus a charge q3 = 3.00 µC as the latter charge moves from infinity to point P (Figure6-b). 40 General physics Phys 2180 Solution: (A) (B) When the charge q3 is at infinity, let us define Ui= 0 for the system, and when the charge is at P, Uf= q3 VP; therefore, 41 General physics Phys 2180 Chapter 5 Capacitance and Dielectrics Definition of Capacitance Consider two conductors carrying charges of equal magnitude and opposite sign, as shown in Figure 1. Such a combination of two conductors is called a capacitor.The conductors are called plates. A potential difference ∆V exists between the conductors due to the presence of the charges. Figure (1) The capacitance C of a capacitor is defined as the ratio of the magnitude of the charge on either conductor to the magnitude of the potential difference between the conductors: From this Equation we see that capacitance has SI units of coulombs per volt. The SI unit of capacitance is the farad (F), which was named in honor of Michael Faraday: 1 F = 1 C/V Calculating Capacitance We can derive an expression for the capacitance of a pair of oppositely charged conductors in the following manner: assume a charge of magnitude Q, and calculate the 42 General physics Phys 2180 potential difference using the techniques described in the preceding chapter. We then use the expression C = Q/∆V to evaluate the capacitance. The electric potential of the sphere of radius R is simply ke Q/R, and setting V = 0 for the infinitely large shell, we have This expression shows that the capacitance of an isolated charged sphere is proportional to its radius and is independent of both the charge on the sphere and the potential difference. 1- Parallel-Plate Capacitors Two parallel metallic plates of equal area A are separated by a distance d, as shown in Figure 2. One plate carries a charge Q , and the other carries a charge -Q . Figure (2) 43 General physics Phys 2180 The surface charge density on either plate is σ = Q/A. If the plates are very close together (in comparison with their length and width), we can assume that the electric field is uniform between the plates and is zero elsewhere. The value of the electric field between the plates is Because the field between the plates is uniform, the magnitude of the potential difference between the plates equals Ed ; therefore, That is, the capacitance of a parallel-plate capacitor is proportional to the area of its plates and inversely proportional to the plate separation. Example 1: Parallel-Plate Capacitor A parallel-plate capacitor with air between the plates has an area A = 2.00 x 10-4 m2 and a plate separation d = 1.00 mm. Find its capacitance. Solution: 44 General physics Phys 2180 2- The Cylindrical Capacitors From the definition of capacitance, we can, in principle, find the capacitance of any geometric arrangement of conductors. Assume a solid cylindrical conductor of radius a and charge Q is coaxial with a cylindrical shell of negligible thickness, radius b , a, and charge -Q (Fig. 3a). Figure (3) The capacitance of this cylindrical capacitor is : 45 General physics Phys 2180 3- The Spherical Capacitor Suppose a spherical capacitor consists of a spherical conducting shell of radius b and charge -Q concentric with a smaller conducting sphere of radius a and charge Q (Fig. 4). Figure (4) The capacitance of this device is given by: 46 General physics Phys 2180 Combinations of Capacitors (1) Parallel Combination Two capacitors connected as shown in Figure 5a are known as a parallel combination of capacitors. The individual potential differences across capacitors connected in parallel are the same and are equal to the potential difference applied across the combination. Figure (5) Let us call the maximum charges on the two capacitors Q1 and Q2. The total charge Q stored by the two capacitors is That is, the total charge on capacitors connected in parallel is the sum of the charges on the individual capacitors. Because the voltages across the capacitors are the same, the charges that they carry are 47 General physics Phys 2180 Suppose that we wish to replace these two capacitors by one equivalent capacitor having a capacitance Ceq, as in Figure 4c. If we extend this treatment to three or more capacitors connected in parallel, we find the equivalent capacitance to be (2) Series Combination Two capacitors connected as shown in Figure 6a and the equivalent circuit diagram in Figure 6b are known as a series combination of capacitors. Figure (6) The charges on capacitors connected in series are the same. From Figure 6a, we see that the voltage ∆V across the battery terminals is split between the two capacitors: 48 General physics Phys 2180 where ∆V1 and ∆V2 are the potential differences across capacitors C1 and C2, respectively. In general, the total potential difference across any number of capacitors connected in series is the sum of the potential differences across the individual capacitors. Because we can apply the expression Q = C ∆V to each capacitor shown in Figure 5b, the potential differences across them are When this analysis is applied to three or more capacitors connected in series, the relationship for the equivalent capacitance is 49 General physics Phys 2180 Example Equivalent Capacitance Find the equivalent capacitance between a and b for the combination of capacitors shown in Figure 7a. All capacitances are in microfarads. Figure (7) Finally, the 2.0 µF and 4.0 µF capacitors in Figure 7c are in parallel and thus have an equivalent capacitance of 6.0 µF. Energy Stored in a Charged Capacitor Suppose that q is the charge on the capacitor at some instant during the charging process. At the same instant, the potential difference across the capacitor is ∆V = q/C. We know that the work necessary to transfer an increment of charge dq from the plate carrying charge -q to the plate carrying charge q (which is at the higher electric potential) is 50 General physics Phys 2180 The total work required to charge the capacitor from q =0 to some final charge q = Q is The work done in charging the capacitor appears as electric potential energy U stored in the capacitor. We can express the potential energy stored in a charged capacitor in the following forms: Because the volume occupied by the electric field is Ad, the energy per unit volume uE = U/Ad, known as the energy density, is The energy density in any electric field is proportional to the square of the magnitude of the electric field at a given point 51 General physics Phys 2180 Problems 1- An air-filled capacitor consists of two parallel plates, each with an area of 7.60 cm2, separated by a distance of 1.80 mm. A 20.0-V potential difference is applied to these plates. Calculate (a) the electric field between the plates, (b) the surface charge density, (c) the capacitance, and (d) the charge on each plate. Solution: (a) E = E = ∆V = d 20 1.8 x 10 −3 = 11.1 x 10 3 volt / m σ εo (b) σ = E ε o = 11.1 x 10 3 x 8.85 x 10 −12 = 98.235 x 10 −9 C / m 2 ε A (c) C = o = d 8.85 x 10 −12 x 7.6 x 10 −4 = 37.367 x 10 −13 C = 3.7367 pF −3 1.8 x 10 (d) Q = C ∆V = 37.367 x 10 −13 x 20 = 74.73 x 10 −12 = 74.73 pC 2- When a potential difference of 150 V is applied to the plates of a parallel-plate capacitor, the plates carry a surface charge density of 30.0 nC/cm2. What is the spacing between the plates? Solution: ∆V = E d = d = ∆V ε o σ σ d εo 150 x 8.85 x 10 −12 = 30 x 10 −9 = 44.25 x 10 −3 m 52 General physics Phys 2180 3- Two capacitors, C1 = 5.00 µF and C2 = 12.0 µF, are connected in parallel, and the resulting combination is connected to a 9.00-V battery. (a) What is the equivalent capacitance of the combination? What are (b) the potential difference across each capacitor and (c) the charge stored on each capacitor? Solution: (a) C eq = C1 + C 2 = 5 x 10 −6 = 17 x 10 −6 + 12 x 10 −6 F = 17 µF (b) The individual potential differences across capacitors connected in parallel are the same and are equal to the potential difference applied across the combination, So ∆V1 = ∆V2 = ∆V = 9 volt (c) Q1 = C1 x ∆V = 5 x 10 −6 x 9 = 45 x 10 −6 C = 45 µC Q2 = C 2 x ∆V = 12 x 10 −6 x 9 = 108 x 10 −6 C = 108 µC 53 General physics Phys 2180 4- Two capacitors when connected in parallel give an equivalent capacitance of 9.00 pF and give an equivalent capacitance of 2.00 pF when connected in series. What is the capacitance of each capacitor? Solution: C1 + C 2 = 9 ∴ C1 = 9 − C 2 (1) 1 1 1 + = 2 C1 C2 1 1 1 + = 9 − C2 2 C2 C2 + 9 − C2 1 = 2 C 2 (9 − C 2 ) 9 C 2 − C 22 = 18 C 22 − 9 C + 18 = 0 (C 2 − 6 ) (C 2 C 2 = 3 pF and from − 3) = 0 or C 2 = 6 pF Eq . (1) C 1 = 6 pF or C 1 = 3 pF ∴ C 1 = 3 pF 54 and C 2 = 6 pF General physics Phys 2180 5- Find the equivalent capacitance between points a and b for the group of capacitors connected as shown in the Figure . Take C1 = 5.00 µF, C2 = 10.0 µF, and C3 = 2.00 µF. Solution: 55 General physics Phys 2180 Chapter 6 Current and Resistance 1- Electric Current The amount of flow of electric charges through a piece of material depends on the material through which the charges are passing and the potential difference across the material. Figure (1) To define current more precisely, suppose that charges are moving perpendicular to a surface of area A, as shown in Figure 1. (This area could be the cross-sectional area of a wire, for example.) The current is the rate at which charge flows through this surface. If ∆Q is the amount of charge that passes through this area in a time interval ∆t, the average current Iav is equal to the charge that passes through A per unit time: If the rate at which charge flows varies in time, then the current varies in time; we define the instantaneous current I as the differential limit of average current: 56 General physics Phys 2180 The SI unit of current is the ampere (A): That is, 1 A of current is equivalent to 1 C of charge passing through the surface area in 1 s. The charges passing through the surface in Figure 1 can be positive or negative, or both. It is conventional to assign to the current the same direction as the flow of positive charge. In electrical conductors, such as copper or aluminum, the current is due to the motion of negatively charged electrons. Therefore, when we speak of current in an ordinary conductor, the direction of the current is opposite the direction of flow of electrons. Figure (2) 57 General physics Phys 2180 2- Resistance Consider a conductor of cross-sectional area A carrying a current I. The current density J in the conductor is defined as the current per unit area. Because the current I = n q vd A, the current density is where J has SI units of A/m2. In general, current density is a vector quantity Note that , the current density is in the direction of charge motion for positive charge carriers and opposite the direction of motion for negative charge carriers. A current density J and an electric field E are established in a conductor whenever a potential difference is maintained across the conductor. In some materials, the current density is proportional to the electric field: where the constant of proportionality σ is called the conductivity of the conductor. Materials that obey above Equation are said to follow Ohm’s law. We can obtain an equation useful in practical applications by considering a segment of straight wire of uniform cross-sectional area A and length L, as shown in Figure 3. A potential difference ∆V = Vb - Va is maintained across the wire, creating in the wire an electric field and a current. 58 General physics Phys 2180 Figure (3) Therefore, we can express the magnitude of the current density in the wire as The quantity R = L/ σA is called the resistance of the conductor. We can define the resistance as the ratio of the potential difference across a conductor to the current in the conductor: The resistance has SI units of volts per ampere. One volt per ampere is defined to be one ohm (Ω): 59 General physics Phys 2180 The inverse of conductivity is resistivity ρ where ρ has the units ohm-meters (Ω.m). Because R = L/ σ A, we can express the resistance of a uniform block of material along the length L as Example 2: Calculate the resistance of an aluminum cylinder that has a length of 10.0 cm and a crosssectional area of 2.00 x 10-4 m2. Repeat the calculation for a cylinder of the same dimensions and made of glass having a resistivity of 3.0 x 1010 Ω.m. Solution Similarly, for glass we find that 60 General physics Phys 2180 Example 3: (A) Calculate the resistance per unit length of a 22-gauge Nichrome wire, which has a radius of 0.321 mm. (B) If a potential difference of 10 V is maintained across a 1.0-m length of the Nichrome wire, what is the current in the wire? Note that "The resistivity of Nichrome is 1.5 x 10-6 Ω.m" Solution: (A) The cross-sectional area of this wire is (B) Resistance and Temperature Over a limited temperature range, the resistivity of a conductor varies approximately linearly with temperature according to the expression where ρ is the resistivity at some temperature T (in degrees Celsius), ρ0 is the resistivity at some reference temperature T0 (usually taken to be 20°C), and α is the temperature coefficient of resistivity. 61 General physics Phys 2180 where ∆ρ= ρ - ρo is the change in resistivity in the temperature interval ∆T= T - T0. we can write the variation of resistance as The Electrical Power Let us consider now the rate at which the system loses electric potential energy as the charge Q passes through the resistor: where I is the current in the circuit. The power P, representing the rate at which energy is delivered to the resistor, is 62 General physics Phys 2180 When I is expressed in amperes, ∆V in volts, and R in ohms, the SI unit of power is the watt Example 4: An electric heater is constructed by applying a potential difference of 120 V to a Nichrome wire that has a total resistance of 8.00 Ω. Find the current carried by the wire and the power rating of the heater. Solution: 63 General physics Phys 2180 Combination of Resistors 1- Series combination When two or more resistors are connected together as in Figure 3, they are said to be in series. The potential difference applied across the series combination of resistors will divide between the two resistors. Figure 3 In Figure 3-a, because the voltage drop from a to b equals IR1 and the voltage drop from b to c equals IR2, the voltage drop from a to c is The potential difference across the battery is also applied to the equivalent resistance Req in Figure 3-b: The equivalent resistance of three or more resistors connected in series is 64 General physics Phys 2180 This relationship indicates that the equivalent resistance of a series connection of resistors is the numerical sum of the individual resistances and is always greater than any individual resistance. 2- Parallel combination Now consider two resistors connected in parallel, as shown in Figure 4. (a) (b) Figure (4) The current I that enters point a must equal the total current leaving that point: Where I1 is the current in R1 and I2 is the current in R2. 65 General physics Phys 2180 An extension of this analysis to three or more resistors in parallel gives We can see from this expression that the inverse of the equivalent resistance of two or more resistors connected in parallel is equal to the sum of the inverses of the individual resistances. Furthermore, the equivalent resistance is always less than the smallest resistance in the group. Example 5: Four resistors are connected as shown in Figure 5-a . (A) Find the equivalent resistance between points a and c. (B) What is the current in each resistor if a potential difference of 42 V is maintained between a and c? Solution: (A) The combination of resistors can be reduced in steps, as shown in Figure 5. The 8.0-Ω and 4.0-Ω resistors are in series; thus, the equivalent resistance between a and b is 12.0 Ω . The 6.0-Ω and 3.0-Ω resistors are in parallel, so we find that the 66 General physics Phys 2180 equivalent resistance from b to c is 2.0 Ω. Hence, the equivalent resistance from a to c is 14.0 Ω. Figure (5) (B) The currents in the 8.0-Ω and 4.0-Ω resistors are the same because they are in series. In addition, this is the same as the current that would exist in the 14.0-Ω equivalent resistor subject to the 42 V potential difference. Therefore, 67 General physics Phys 2180 This is the current in the 8.0-Ω and 4.0-Ω resistors. When this 3.0-A current enters the junction at b, however, it splits, with part passing through the 6.0-Ω resistor (I1) and part through the 3.0-Ω resistor (I2). Because the potential difference is Vbc across each of these parallel resistors, we see that: (6.0 Ω) I1 = (3.0 Ω)I2, or I2 = 2I1 Using this result and the fact that: I1 + I2 = 3.0 A Then : I1 = 1.0 A and I2 = 2.0 A. Example 3 Three resistors are connected in parallel as shown in Figure 6-a. A potential difference of 18.0 V is maintained between points a and b. Figure 6 68 General physics Phys 2180 (A) Find the current in each resistor. (B) Calculate the power delivered to each resistor and the total power delivered to the combination of resistors. (C) Calculate the equivalent resistance of the circuit. Solution: (A) (B) We apply the relationship P = I2R to each resistor and obtain (C) 69